Читать книгу Walking in Carmarthenshire - Jim Rubery - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The very pleasant footpath through Coed y Castle (Walk 16)

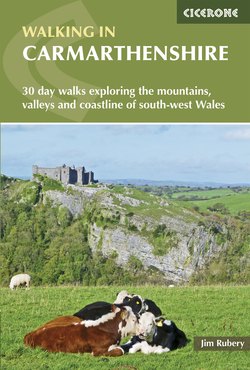

With vast stretches of golden sands, breathtaking mountain scenery, fast-flowing rivers, quiet upland lakes, pretty market towns, isolated farmsteads, extensive tracts of forest, evocative castle ruins, empty country lanes and a rich industrial heritage, it is not surprising that Carmarthenshire is one of the most beautiful counties in Britain. Add to this the fact that it has around 3000km of footpaths, bridleways, green lanes and byways, the vast majority of which are well kept, clearly waymarked and furnished to a high standard with gates and stiles, it is hardly surprising that it is a paradise for walkers who can explore these gems at their leisure.

Carmarthenshire is often overlooked by visitors, as they speed ever westward along the M4 and A40 towards its southwesterly neighbour, Pembrokeshire. To many, it’s not so much a place to terminate the journey and explore but more that bit to pass through between Swansea and St Clears. In some ways this is a real shame because the county is stunningly beautiful with a rich diversity of landscapes. For the discerning walker, however, who has already discovered the treasures of Carmarthenshire, it is something to celebrate, as the footpaths, tracks and bridleways remain largely peaceful and devoid of people.

Covering some 2398 sq km (11.5 percent of total Wales land mass), Carmarthenshire, or to give it its correct Welsh name, Sir Gaerfyrddin, is the third largest county in Wales. It has always been a large county, and up to 1974 held the accolade as the largest in Wales. During that year, following a seriously provocative set of boundary and authority changes, Carmarthenshire ceased to exist, being swallowed up, along with Pembrokeshire and Cardiganshire, in the new county of Dyfed. In 1996 it reappeared, following a further bout of reorganisation and boundary change; not quite in its original guise, but the one that we see today.

It is a county of great contrasts, stretching from the sandy beaches of Carmarthen Bay in the south to the empty uplands of the Cambrian Mountains in the north; from the high mountains of Y Mynydd Du in the east to the gently rolling farmland, along the Pembrokeshire border, in the west. Agricultural landscapes predominate, but among the folds of the hills and along the river valleys, there is a good spattering of pretty market towns, all of which are friendly, full of character and offer a range of places for refreshment or accommodation. The most extensive urban landscape occupies the southeastern corner of the county, an area that is also home to 65 percent of its resident population, who live in or around the towns of Llanelli and Burry Port, now both transformed from their industrial past.

Landscape and geology

As with the rest of Britain, the geological events that initially shaped Carmarthenshire occurred hundreds of millions of years ago, south of the equator and beneath warm tropical seas. For the past 425 million years, the continental plate, on which we stand, has been drifting imperceptibly northwards. For the most part, the exposed rocks of Carmarthenshire are sedimentary and consist largely of a mixture of shales, conglomerates, sandstones and mudstones, with Millstone Grit and Carboniferous Limestone forming the northwestern rim of the South Wales coalfield, which extends into Carmarthenshire in the southeast of the county, but which is also exposed in the sea cliffs running westward from Pendine towards Pembrokeshire.

Almost the whole of the county is hilly or mountainous, the exception being the southern coastal fringes. On its eastern borders, abutting the county of Neath-Port Talbot and Swansea, rise the imposing range of the Mynydd Du (the Black Mountains) and the westernmost part of the Brecon Beacons, where the county’s ‘top’ can be found in the shapely form of Fan Foel, standing at a proud 781m (2562ft). These north facing escarpments are formed from Old Red Sandstone, rocks of Palaeozoic age that were moulded, like the rest of Wales, during the late Tertiary period when they were thrust skyward to form hills and mountains. Glacial erosion during the Pleistocene ice ages greatly modified their contours, along with wind, rain and snow in more recent times. Outcrops of Millstone Grit and Carboniferous Limestone add to the geological mix. The area also forms part of the Fforest Fawr Geopark, the first of its kind in Wales, set up to promote the wealth of natural and cultural interest in the area. Here, as elsewhere in Wales, there is a high degree of correlation between rocks and relief.

Creek and mudflats near Burry Port (Walk 22)

In the north of the county, adjoining Ceredigion and Powys, rise the Cambrian Mountains of Mid Wales, one of the largest expanses of wilderness south of Scotland and largely composed of sedimentary sandstones and mudstones. Their geological history is not dissimilar to the Myndd Du, but their current features are the product of thousands of years of interaction between an exposed upland environment and the few communities that have succeeded in creating their livelihood there. In the past, the name ‘Cambrian Mountains’ was applied in a general sense to most of upland Wales, including Snowdonia and the Brecon Beacons. During the 1950s, the name became synonymous with the homogenous upland region of Mid Wales that includes Pumlumon in the north of the region, Elenydd in the middle and Mynydd Mallaen in the south. Due to its beauty and unspoilt nature, in 1965 the National Parks Commission proposed the area be given National Park status, although this has not happened.

It is the southern part of the Cambrian Mountains that lies within Carmarthenshire’s borders, a vast expanse of rolling hills and quiet valleys comprising the Mynydd Llanllwni, Mynydd Mallaen and Rhandirmwyn, where the bleat of sheep, the splashing of streams and the call of the red kite and buzzard are likely to be all you hear as you roam these empty landscapes. Two of Carmarthenshire’s principal rivers rise in these mountains, the Teifi, a spectacular river and one of the most important rivers for wildlife, which forms the northern county boundary with Ceredigion. The other is the Tywi, a remarkably beautiful river that flows for 121km before emptying into the brackish waters of Carmarthen Bay at Llansteffan, navigable since Roman times.

The long track beneath the northern slopes of Y Mynydd Du (Walk 18)

The west of the county is more rolling and largely given over to beef and dairy farming. It is also where you will find the county town, Carmarthen, the most important town in west Wales for almost 2000 years and the oldest continuously occupied settlement in the whole of Wales since Roman times.

The south of the county is bordered by Carmarthen Bay, abutted to the east by the Gower Area of Outstanding National Beauty and to the east by Pembrokeshire Coast National Park. In between these two ‘book ends’ lie 129km of golden sandy beaches, ever changing river estuaries, awe-inspiring castles and pretty coastal towns, now all linked by the Carmarthenshire section of the Wales Coast Path. It is here that the largest town in the county can be found, Llanelli, situated in its southeastern corner, on the Loughor Estuary and famous for its proud rugby tradition, but also for its tinplate industry. It is in this area that Carmarthenshire’s chief coal deposits were found, an extension of the South Wales coalfield, with most of the mining occurring in the Gwendraeth Valley and Llanelly districts. The county has few other mineral deposits of note. Limestone was quarried and burnt in the Black Mountains, mainly for agricultural use, but metallic ores are rare, with small quantities of iron-ore being mined in the hills around Llandeilo and Llandovery and much smaller quantities of gold being extracted near Pumsaint.

History

Carmarthenshire is dotted with prehistoric remains, including burial chambers, standing stones, hill forts, tumuli and stone circles, very few of which have been excavated adequately and few of these have been dated scientifically. One exception is Coygan Cave, a limestone cave near Laugharne, now destroyed by quarrying but which was extensively excavated and produced archaeological finds that included two hand axes of Mousterian type associated with Neanderthals, from about 50,000 years ago. Other palaeo-ecological work has shown that human exploitation of this region occurred from round about this time, albeit with varying and uneven intensity, but particularly the expansion of activity from the late Neolithic, which can be equated with a general growth in settlement and agriculture, similar to the rest of the British Isles.

When the Romans invaded Britannia in AD43, Carmarthenshire formed part of the lands of the Demetae tribe, a Celtic people of the late Iron Age. Following their submission, the Romans built a fort at Carmarthen, Moridunum, followed by others at Loughor, Llandeilo and Llandovery. They also had a settlement at the Dolaucothi Gold Mines near Pumsaint.

When the Romans departed, South Wales returned to the same structure of small, independent kingdoms as in the Iron Age, with the Demetae taking control of Carmarthenshire, enlarging the town of Moridunum and using it as their capital, thus making it the oldest, continually inhabited settlement in Wales. The town eventually became known as Caerfyrddin, anglicized into Carmarthen, which subsequently gave its name to the county.

During the fifth and sixth centuries, Carmarthenshire’s inhabitants became more civilised and were also introduced to doctrines of Christianity, thanks to a group of hard working Celtic missionaries, notably St David and St Teilo. In the ninth and 10th centuries, the influx of Irish from the west and British from the east began to test the tribal boundaries and in AD920, Hywel Dda, the prince of South Wales, scrapped old kingdoms and created four new ones, Gwent, Gwynedd, Powys and Deheubarth, the latter including the region of Carmarthenshire.

In 1080 the Normans first appeared on the shores of Carmarthen Bay and following numerous skirmishes, conquered Deheubarth in 1093. By the end of King Henry I’s reign, in 1135, the great castles of Kidwelly, Carmarthen, Laugharne and Llanstephan had been constructed. Although the former kingdom of Deheubarth briefly re-emerged in the 12th century under Maredudd ap Gruffydd and the Lord Rhys, the Normans soon re-exerted control and Deheubarth ceased to exist as a kingdom after 1234. By the Statutes of Rhuddlan (1284), Edward I formed the counties of Cardigan and Carmarthen and in the ensuing years, the prosperity of the new county increased considerably, resulting in Edward III naming Carmarthen as the foremost town in Wales for the wool trade.

Afon Teifi at Cenarth (Walk 2)

In the reign of Henry IV, Owain Glyndwr, the last of the Welsh Princes, upset the apple cart for a time, having obtained the assistance of an army of 12,000 men from France and, being joined by several of the Welsh chieftains, he set about regaining control of the country. Unfortunately for him, his battle plan was flawed, particularly with regard to a lack of artillery to defend his strongholds and ships to protect the coastline, and in 1409 he was driven out of the area by the superior resources of the English. Amazingly, he was never captured, despite a huge ransom on his head.

Following the Civil War in the 17th century, the castles of Carmarthenshire that had supported the royal cause soon fell to the parliamentarian forces, resulting in Cromwell ordering their dismantling and so preventing their use in any further skirmishes.

Old barns at Ty hen (Walk 3)

In the ensuing years, the great Welsh spiritual and educational movement had its roots in the little village of Llanddowror, where the celebrated and pious vicar, Griffith Jones, had become the founder of the Welsh circulating charity schools.

Nature reserves and wildlife habitats

In a county as large as Carmarthenshire, and with so many diverse habitats, it is not surprising that nature and wildlife is well catered for. The county is justly renowned for its magnificent coast, quiet estuaries, steep wooded valleys and vast expanses of mountain and moorland. On top of this there are hundreds of kilometres of hedgerow and hedgebank, many of which are of historical importance. With the patchwork of woodlands throughout the county and the thousands of acres of fields, it soon becomes evident that the biodiversity is huge. Add to this the rich abundance of species that live in the sea and on the seabed around the Carmarthenshire coast and the wildlife habitats increase even more.

The magnificent ruins of Laugharne Castle (Walk 26)

The Mynydd Du, in the east of the county, falls largely within the boundaries of the Brecon Beacons National Park and all the protection legislation that that affords. There are 12 nature reserves, cared for by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales and 81 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), covering over 17,000ha and ranging in size from small fields to long rivers, disused quarries to large areas of mountainside, and this excludes the ones that are found in the Carmarthenshire part of Brecon Beacons National Park. There are two Special Protection Areas (SPA) and seven Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), sites considered to be of international importance for nature conservation. Carmarthenshire also has five Local Nature Reserves (LNRs), sites designated by local authorities as supporting a rich variety of wildlife or geological features and which allow local people contact with the natural environment. The RSPB have a reserve at Gwenffrwd-Dinas, in the north of the county and there is also the splendid National Wetlands Centre Wales, on the Bury Inlet, where it is possible to see wild birds up to 50,000 strong during the winter months.

Market hall, Laugharne (Walk 26)

Transport

Swansea, Llanelli and Carmarthen are the main transport hubs in the area, all being on the inter-city route from London Paddington to South and West Wales. The Heart of Wales Railway Line, although not as fast or as frequent, links Shrewsbury to Swansea, calling at Llandovery, Llandeilo, Ammanford and several other stops before terminating in Swansea.

The M4 motorway and the A48 dual carriageway run east to west through the county, while the A40 runs northeast to southwest, passing along the Tywi Valley and through Carmarthen and St Clears. There is also an extensive network of other A-roads and numerous minor roads throughout the county, with good access to all the major towns and villages. There is an excellent bus service, particularly between the main towns, and even many of the remote villages have a service, although these may not be as frequent and non-existent on a Sunday.

See Appendix B for useful contact telephone numbers and website links.

Staying in Carmarthenshire

Carmarthenshire is a recognised tourist destination and as such is well served with all types of accommodation, including B&Bs, hotels, self catering options and many caravan, camping and even glamping sites. The seaside resorts are very popular and tend to book up early for the main school holiday weeks. Away from the main towns, accommodation is less frequent, particularly in the mountainous areas, where a little forward planning is advised.

Looking north along Cwm Lliedi Reservoir (Walk 21)

For Walks 1–4, ‘In and around the Teifi Valley’, Newcastle Emlyn would be a suitable base to stay as it has a good range of accommodation, along with Llandysul. For Walks 5–8, ‘Castles, gardens and forests’, either Carmarthen or Llandeilo would be suitable centres. Llandovery has the most diverse range of accommodation for Walks 9–12 ‘The Cambrians of Carmarthenshire’, and it would also serve as a good base for the Walks 13–18, ‘The high mountains of Y Mynydd Du’, along with Llandeilo and the towns and villages in the Amman Valley to the south. The area containing Walks 19–23, ‘History and heritage’, provides the largest choice of places to stay, with Llanelli, Burry Port, Pembrey, Kidwelly and Ferryside all having a range of accommodation providers. Finally, Walks 24–30, ‘Dylan Thomas Country’ are also well served with Llansteffan, Laugharne, Pendine and St Clears being good bases.

Please refer to Appendix B for details of websites, addresses and telephone numbers that may assist with a stay in Carmarthenshire.

Clockwise from left: common orchids; a wildflower-strewn meadow; cinnabar moth on thistle; rowan berries

What to take

Much of Carmarthenshire’s weather comes winging in on southwesterly air streams, meaning rain is always a possibility, so a good set of quality waterproofs is a must, along with a few spare warm layers for cold or windy days. Also, a number of the walks venture out into high moorland and mountain terrain, where conditions underfoot can get pretty wet, so a stout pair of waterproof boots is also recommended. Because weather conditions can change quite rapidly, particularly on high ground, the appropriate map, a compass and a whistle should also be packed. That said, warm, sunny days are equally likely and the southwesterly air streams tend to bring mild conditions. Because of the county’s outstanding array of scenery and prolific wildlife, a camera and binoculars are also worth packing.

Maps and waymarking

The walks in this book are covered by seven 1:25,000 Ordinance Survey maps:

Outdoor Leisure 12 (Brecon Beacons National Park. Western area)

Explorer 164 (Gower)

Explorer 177 (Carmarthen & Kidwelly)

Explorer 178 (Llanelli & Ammanford)

Explorer 185 (Newcastle Emlyn)

Explorer 186 (Llandeilo & Brechfa Forest)

Explorer 187 (Llandovery)

Cenarth (Walk 2)

Waymarking is generally very good to excellent, apart from on some of the exposed ridges, moors and mountains, where a map and compass may be necessary; GPS signals are fine in most areas. The furniture on most of the walks is good, with sound stiles and many new pedestrian and kissing gates. Many of the walks pass through woodland where fallen trees may present an obstacle. Where such obstacles were found, mention is made in the text and, if necessary, an alternative route given.

‘Carmarthenshire Footpaths’ sign

Using this guide

There are 30 walks in this guide, 26 of them being circular and four of them being linear along sections of the Carmarthenshire Coast Path (CCP). The walks are organised into six loosely defined geographical areas. Walks 1–4 cover the northwestern area, Walks 5–8 the central region, Walks 9–12 the Cambrian Mountains and upper Tywi Valley, Walks 13–18 the Y Mynydd Du (the Black Mountains), Walks 19–23 the southeastern part along Carmarthen Bay and Walks 24–30 the southwestern corner and holiday resorts along that stretch of coast.

The Tywi Valley from Carreglwyd (Walk 15)

Some are relatively short excursions that can easily be completed in a few hours, while others require considerably more time and can be quite challenging as they head out into open country, where knowledge of map and compass use is highly recommended.

The time needed to complete the walks will vary, depending on fitness, experience and even the composition of a party, should there be several people attempting a walk together. However, it is roughly based on a person being of reasonable fitness and able to cover around 2mph.

In places, it’s possible to link some of the walks together to make a lengthier outing, or even to shorten some, should time be an issue. Where this is the case, there is mention of the fact in the introductory paragraph to the walks concerned. The four linear walks, along the CCP, all have good bus or rail (or both) links back to the start.

Routes are illustrated with extracts from the OS 1:50,000 Landranger maps, but it is highly recommended that the relevant 1:25,000 Explorer maps also be referenced and carried. The main route is highlighted in orange, with any alternative route marked in blue. In such cases, the alternative route is described in the main route description. Features along the way that appear on the map are highlighted in bold in the main description.

The contents of this book hardly scratch the surface of the plethora of potential walks that are available in Carmarthenshire, but I hope you enjoy any that you attempt and that it whets your appetite for walking in this fabulous county.