Читать книгу Ordinary Sins - Jim Heynen - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAFTER THEOPHRASTUS?

Theophrastus (circa 371 BC to circa 287 BC) may not be the earliest short-short story writer, but he caught my attention in high school where our literature text carried a sampling of his Characters. These brief verbal snapshots of people suited my adolescent attention span, and their appeal stuck with me.

Before Theophrastus, there was nothing quite like his character sketches. We can find some precedent in Homer, Plato, and especially Aristotle. But even in Aristotle’s analysis of moral virtues and vices, the human qualities remain quite abstract. In Theophrastus we see lively, flesh-and-blood people like “The Toady,” who “is the sort of man who says to a person walking with him, ‘Are you aware of the admiring looks you are getting?’” or “The Man of Petty Ambition,” who “is apt to buy a little ladder for his domestic jackdaw and make a little bronze shield for it to carry when it hops onto the ladder” or my favorite, “The Late Learner,” who “is the kind of man who at the age of sixty memorises passages for recitation and while performing at a party forgets the words.”

Most of the biographical information available about Theophrastus was written several centuries after his death by Diogenes Laertius in Lives of the Philosophers. We do know that he studied with Plato and later began to associate with Aristotle in Athens. After Aristotle’s death he became the head of the Lyceum and remained its head until his death at age eighty-five or eighty-six. He inherited Aristotle’s books (which were stored underground and damaged) and may have had as many as two thousand students. He was a learned man and prolific writer, whose works covered a wide expanse of human knowledge, both in science and philosophy. His several-volume work, On the Causes of Plants, for example, prompted some to label him the “father of botany.” I like the fact that his study of plants made him one of Western history’s earliest vegetarians, believing, as he did, that animals have feelings like human beings.

Theophrastus’s given name was Tyrtamus but Aristotle nicknamed him Theophrastus (god/to phrase)—that is, “divine expression”—to acknowledge his graceful way of speaking. Reportedly, he was a fine and witty lecturer, and some scholars speculate that his character portrayals from fourth-century BC Greek society were models for orators.

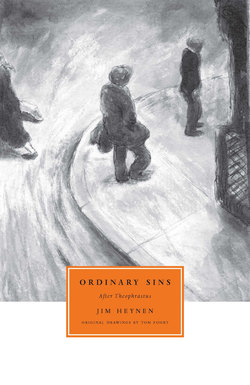

Was the audience laughing in response to the recitation of Theophrastus’ Characters? Blushing? Insulted? Whatever the answers, I never sense real malice in Theophrastus. I hope the same is true in this collection. In fact, I’d like to think that Theophrastus was gently mocking himself in some of his portrayals. I certainly am in many of the stories in Ordinary Sins, several of which are thinly disguised self-portraits. You are welcome to find Waldo, if you can.

JIM HEYNEN

Note: There is now a six-hundred-page work devoted to these fourth-century BC short-shorts: Theophrastus Characters, edited, commentary, translation and introduction by James Diggle (Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries 43, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). Diggle suggests that the title, Characters, is misleading, and could more accurately be Behavioral Types or Distinctive Marks of Character. My quotations are from Diggle’s book.