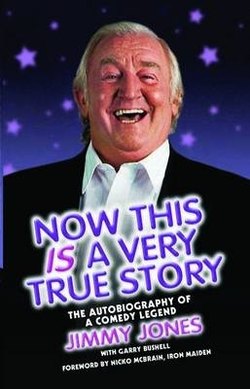

Читать книгу Now This is a Very True Story - Jimmy Jones - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WELCOME TO THE HOUSE OF FUN

ОглавлениеI WAS STILL a teenager when I found out firsthand about the fringe benefits of a life in showbusiness. At the age of 16, like most kids at the time, I bought myself a motorbike. It was the next door neighbour’s 125 Excelsior, and I bought it off him for £25 which I raised by working for good old Charlie Cutbush.

I’d passed my driving test by then. I still used to see Charlie but not as much as before, because I’d got myself a job on a building site as a plasterer’s labourer. I used to hang out at the Four Oaks, a bikers’ cafe on the A13. It was owned by a fella called Tommy Asquith, who used to have his own puppet show. He’d heard me singing one night in the Silver Lion Social Club which was at the back of the café and he invited me to do a show with him at the Guisborough Social Club in North Yorkshire – four nights, Thursday to Sunday, for eight quid. He said you can follow me up, do the show and I’ll pay for your digs as well, which sounded to me like a result.

When we got up there on the Thursday he introduced me to the club secretary whose house I was staying at, and told me he’d put me on not before the interval, but the act before that. I couldn’t figure out why he’d done it until that night. The act who followed me was a magician, I’ll never forget it. Right in the middle of his major trick with all the doves, the club chairman banged on the table and said, ‘T’pies have arrived,’ in an accent that could have been scrapped off the walls of ’kin’ Kinsley colliery. He was so Northern he made Colin Compton sound posh. Immediately the audience got up and left him right in the middle of the bloody trick; they didn’t give him a chance, they all wanted a pie. Even the doves were queuing up. And Tommy said, ‘Now you know why I put you in second on the bill in the first half.’ This kind of thing was par for the course in the Northern clubs. Peter Kay’s Phoenix Nights could have been a documentary.

Tommy was the big act, and he used to close the show. That night, the club secretary took me home, gave me a bit of supper and introduced me to his daughter Maureen who was a stunning young girl who looked about my age. She had blonde hair, blue eyes and a lovely pair of bristols; she had a cute smile too and she was very flirty.

In the middle of the night this Maureen came and crept in bed with me and what followed was as wonderful as it was inevitable. When we finished, she kissed me on the cheek, got up and went back in her own bed.

This happened on the Thursday night, the Friday night and the Saturday night. I shafted her all over the weekend. I was leaving on the Monday morning, so on the Sunday night her father gave me a pull and said, ‘Don’t keep Maureen up too late tonight, she’s got to get up for school in the morning.’ That frightened the bleedin’ life out of me, I can tell you. We got in the bed and I said to her, well how old are you? She said, ‘I’m 14.’

For crying out loud! I knew the law at that time and I thought, I could be nicked here! It frightened me because I’d given her enough rod to put a hand-rail round Harrogate.

But I still gave her one before I fucked off.

The following morning I was up with the cock – again, on the motorbike and off like a bloody rocket. I didn’t even say goodbye to her. My bike was older than Maureen was. Granted she had better acceleration and a quieter exhaust, but at least the motorbike was legal to ride.

Looking back now, I consider those three days as a bit of a Triumph.

* * * *

I’d left school at 15 with no qualifications. I could add up, nobody would ever have me over for a quid, but even now my writing looks like a spider has crawled over the paper. I was a grafter, though, and the bike made me properly independent. I could drive myself to work and to shows. I didn’t have to rely on anyone else any more, which was just how I liked it.

By the age of 17, people started to take notice of me. I was working the British Legion club down the Walworth Road in south London. It was an odd place; the entertainment secretary always used to warn you not to stay on stage for an extra song after your allotted time. This was for the very good reason that, if you did, you’d be wasting your time as the train went by every half hour and rocked the building for so long no one would have heard you. All you could hear was the bloody train. Of course it wouldn’t apply now because these days the trains are always delayed.

This particular night, Larry Parnes the famous impresario was in and he came backstage after I’d sung and asked me if I could raise £250. I said, ‘Are you joking, it was hard enough raising £25 for me bike.’ He said ‘That’s a pity because if you could raise £250 I could get you a record contract.’ We used to call him ‘Parnes, Shillings and Pence’ cos Larry was very reluctant to part with a pound note.

Well I didn’t have a snowman’s chance in the Sahara of raising that kind of dough. I was only getting paid £1.50 for a show. There was more chance of me giving Princess Margaret one. But there was another guy on the bill with me by the name of Tommy Hicks from Bermondsey, and his mother and father had a greengrocer’s at the time, and they raised the money for Tommy to take Larry up on his offer. And, of course, Tommy Hicks became Tommy Steele, who had his first hit a year later in 1956 with ‘Rock With The Caveman’, and his first Number One two months after that with ‘Singin’ The Blues’.

Just think, if I could have raised half a monkey that might have been me singing ‘Half A Sixpence’ on Broadway as opposed to singing for two and sixpence in the Broadway, Dagenham…

When I wasn’t out working as a singer, I would still enter whatever talent shows were going and work for free. There were a few of us who used to go in for all of these contests at the time. It was generally the same little crew, you may have heard of them. There was Queenie Watts who became a famous actress, Tommy Bruce, who sounded a lot like Louis Armstrong and had a Top Three hit in 1960, the singer Kim Cordell from Clacton who did a bit of telly in the ’60s, and a fella from Shoreditch by the name of Terry Parsons who changed his name and became an international showbusiness legend as Matt Monro.

Back then he was a bus driver; he worked out of Plaistow bus garage. He certainly rang the bell later on with massive international hits such as ‘Born Free’, ‘Walk Away’ and ‘Softly As I Leave You’.

The best of these pub talent contests was at the Rising Sun in Bethnal Green on a Tuesday night. I’d win one week, Queenie would win the second, then Matt, then Tommy… and we’d all come back for the big final. It was very competitive and the standards were sky high – far higher than they are on TV talent shows today. So there started to be a bit of a buzz about the place. I was in the pub one night when the legendary Judy Garland came in to watch the turns. Eventually the Rising Sun talent nights inspired the ATV television series Stars and Garters, which tried to recreate the feel of a variety show in your local pub. It made stars of Kathy Kirby, Vince Hill and my old mate Tommy Bruce. The compère on the TV show was Ray Martine – not Welsh George who did it in the pub – but they did use the pub band, the Don Harvey Trio, who were to figure in my life a fair bit. There was Don Harvey on organ, Eric Cornish on drums and George Watkins on bass.

On TV, the audience consisted of extras mixed with real regulars from the Rising Sun. Only non-alcoholic drinks were served but they did hand out free cigarettes. Ray Martine was a good comic from the Deuragon Arms in Hackney, but his routine was so blue that ATV had to bring in Barry Cryer, Dick Vosburgh and Marty Feldman to write clean gags for him.

Back in the real world, the Rising Sun nights were such a runaway success that other pubs followed suit. A guy called Daniel Farson started to run talent nights on the Isle of Dogs, with Martine as compère. He also put on a show called A Night At The Comedy in the West End with top turns such as Kenny Lynch and Vince Hill and a young up-and-coming Scouse comedian called Jimmy Tarbuck. Then he would have two acts competing in the new talent part of the show. One particular night, it was me versus Queenie Watts, and when Ray asked the audience who’d won, this one fella was most insistent. He said that Albert Simmonds was sensational and that he wanted to meet me after the show and give me his professional advice. I was thrilled and intrigued. It turned out he was a showbiz journalist called Godfrey Wynn from the Sunday Express – he was said to have been the highest paid columnist in Fleet Street, where his nickname was Winifred God. But Daniel and Ray pulled me over and said, ‘Be careful of this bloke because he’s not quite kosher’. I was 17 and didn’t know what they were getting at, so they spelt it: the guy was gay, and quite predatory. He’d give me some column inches in the newspapers all right but he would also want to slip a column up the back – where The Sun don’t shine.

Just as they’d predicted, I was propositioned straight afterwards. Godfrey came and spoke to me and his first words were, ‘I could put you on top of the tree.’

And me, being a cocky little bastard, said, ‘That’s very kind of you but I’m not a fairy.’ So there was my leg-up out the window, along with his leg-over.

Ray was gay himself, he just didn’t like men with a thing for underage kids.

A Night At The Comedy was an absolutely fabulous show. Ray Martine had a sidekick in Kim Cordell, and there was another regular on the bill called Mrs Shufflewick who was a drag act and very, very funny indeed; Shufflewick was a legend in variety theatre circles. She was played by Rex Jameson, and the character was a drunken old Cockney charlady whose stories got dirtier the more she drank her port and lemon. We knew her as Shuff.

Jimmy Tarbuck closed the first half, and top of the bill was the brilliant Northern comedian Jimmy James who we all called Stumpy Marsh because he had a bad leg; Roy Castle was his stooge. Queenie Watts opened the second half with a song and then it was all down to Jimmy James. Tarbuck and I would sit and watch him six nights a week. We never missed a show. He was wonderful, a real comedian’s comedian. We would just turn to each other and say, ‘Look at his timing!’ It was stunning, absolutely impeccable. He did a drunk sketch, an elephant in a box set, and his act was word perfect. It’s an over-used phrase, but Jimmy James really was a comedy icon.

Ironically, off-stage James was a teetotaller, he wouldn’t touch a drop, but no one played a better drunk. I can still see him now, lurching across the stage while ‘Three O’Clock In The Morning’ played in the background, his top hat askew, shirt out at the front, a wilting fag in his hand… wonderful. Jimmy’s big problem was gambling. He loved a flutter and was declared bankrupt three or four times, but he was a very generous man. He got Bernard Manning his first agent, but then no one’s perfect.

The show ran for about two months, maybe more, before the Lord Chancellor closed it. Because in the West End in those days, if you did anything even slightly naughty, if there was any bad language or risqué suggestions, then bang, the show would be closed. I remember the intense disappointment when I got there one Saturday night and the old boy on the stage door told me: ‘Not tonight, Albert.’

‘Why’s that?’

‘The Lord Chancellor was in at lunchtime, Mrs Shufflewick went over the top and they’ve closed the show.’

And that was it, Shuff had gone blue in the matinee and we all lost out. Some people in the cast said that was just an excuse and speculated that the real reason for closure was that Daniel Farson had run out of money. I don’t know if that was true, because we always played to packed houses, and besides, it didn’t make any difference to me because I didn’t really get paid anyway. But A Night At The Comedy ended for good that day. It would be a night with no comedy from now on.

I was never close to Jimmy Tarbuck but we were always friendly, and even now if I go into a theatre where he has appeared the night before he’ll leave me a little note, along the lines of, ‘Follow me around like this Jonesy and you’ll soon be a star’.

As for Mrs Shufflewick, the problem was Rex was a pisshead. When Shuff was on at the Hackney Empire the production manager locked her in the dressing room to keep her off the pop but she was still getting legless and no one could work out how. Shuff was actually bribing a stage hand to buy half a bottle of whisky and stand outside the dressing room door while she drunk through the keyhole with a couple of joined-up straws. Her act got bluer the more she had to drink, so it was easy to see how she could have gone OTT at the matinee. I loved the act, it was all filth. She’d say things like: ‘Do you like this fur, girls? It cost £200. I didn’t pay for it meself; I met 200 fellas with a pound each… This is very rare, this fur. This is known in the trade as “untouched pussy” – which as you know is unobtainable in the West End of London at the moment. And I don’t think there’s much knocking around here tonight.’

She had a story about a shoemaker who made a pair of boots for Queen Victoria and stuck a sign in the window that read ‘Cobblers To The Queen’. The Palace made him take it down, so he replaced it with another one: ‘Bollocks To The King.’

* * * *

I was 18 when I met my first wife in the most romantic of locations, the Four Oaks café. All the herberts and ton-up boys used to get in there, the air was full of exotic aromas: frying bacon, the smell of coffee and petrol fumes. Gracie Lock was a good-looking girl. She caught my eye and we hit it off immediately. I laughed her into bed and the next thing I knew Gracie was pregnant. It was my fault, I should have taken precautions; I should have given her a false name.

Being a boy of 18 years of age I wasn’t ready to settle down but my girlfriend was expecting and in those days it meant you got married. You were brought up to do the right thing. So I did. We tied the knot on 5 January 1957. And three months later, on St George’s Day, 23 April, she gave birth to my lovely son Paul.

Not an ideal start to married life, but I’m immensely proud of my family: four boys and two girls, who have given me 17 grandchildren aged between ten and 31, and nine great grandchildren – ten by the time this book is published.

I couldn’t keep a wife and my son afloat on the money I was making from my act, which was still singing, whistling and bird impressions, so I was working in the building trade as a plasterer until the guy I was working for very inconveniently went and died on me.

I got myself another job as a tiler’s labourer which entailed exactly the same kind of thing – knocking off muck and hard work. I learnt to lay tiles, just as I’d learnt to become a plasterer, by picking the job up as I went along and helping out whenever I could.

At the time, Grace and I were living separately, her with her mum and me with mine, and then she went to live with a friend over in Dagenham. But I must have been making plenty of journeys over to see her because pretty soon she became pregnant again, this time with Helen.

To sort out our living arrangements, I finally met a lady councillor, turned on the charm and persuaded her that the council should give us a house. It was a right dump because the people living in it before had let it go to rack and ruin, but the council said we could have it providing I agreed to clear it up. I jumped at the chance. And that our first home together, 34 Sunnings Lane, Upminster.

To show what a family man I was, I traded my motorbike in for one with a side car. We had some fun and games on that. One night in particular we’d been visiting our parents in Rainham and were driving home, with my son on the back of the bike with me and my wife in the side car with the baby. It was near Christmas and this Old Bill stopped us on a country lane and demanded to know if I had any chickens in the side car. I said, ‘You’re having a laugh aren’t you mate?’

Apparently a crowd of herberts had raided a local poultry farm and half-inched all the chickens. And this cop only made Grace and the baby get out of the side car so he could search it for chickens. The dozy bastard. We had plenty of stuffing back then, but no stolen chickens.

It was just as well I never volunteered to show him my prize cock.

A chicken walks up to a duck at the side of road. He says, ‘Whatever you do don’t cross, mate, you’ll never hear the ’kin’ end of it.’