Читать книгу I'm Your Girl - J.J. Murray - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

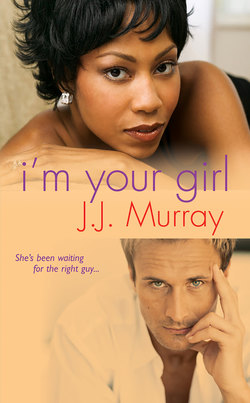

1 Diane Denise “Dee-Dee” “Nisi” Anderson

ОглавлениеThis game is rigged.

I know it’s only solitaire, but these cards just don’t want to fall for me tonight. For seven games in a row, the ace I’ve needed to win has been hiding in the last pile on the right, and twice it’s been the bottom card.

It serves me right for playing solitaire on Christmas Eve.

Solitaire is a funny game. It takes a long time to win, and when you do, you keep playing—and losing—until you win again. It’s just something to do with my hands, to keep them occupied. “Idle hands,” my mama used to say to me, and I’d finish the phrase: “are the Devil’s playground.”

I’ll bet even the Devil cheats at solitaire.

Solitaire is kind of like life, I guess. You fuss and scratch to get into college, take the right courses, get the degree that you hope will take you through the rest of your life, get that diploma…then lose your mind trying to find a job that matches that diploma. I have a degree in library science, and, yes, it is a science to run a library. I figured that this country, with thousands of libraries, would have openings wherever I looked, especially for a suede-skinned sister like myself.

I was wrong.

While I was doing some part-time work at libraries in my hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana—and living with my mama, but that’s another story—I was sending résumés to libraries all over the country. Most never responded, and four wrote nice “no-thank-you” letters, leaving me with interviews in Chicago, Louisville, and Roanoke, Virginia.

I had to look up that last place on a map.

And, of course, Roanoke is where I ended up. My official title is Grade Four Clerk, because I actually have a library science degree. I’m a clerk. I’m not “Assistant Librarian,” not a “Media Specialist”—just a Grade Four Clerk, as if I’m working in an elementary school somewhere. I shelve books, reshelve books, scan bar codes, compile overdue lists, conduct reference interviews until my voice gets hoarse, and occasionally help coordinate Saturday morning readings for the kids. Yeah, that’s me behind the circulation or reference desk, eyeing every person wandering into the library, forcing a smile and making change for the copier.

And…that’s…about…it.

“Give me a king, please!”

And I’m talking to a deck of cards on Christmas Eve.

It’s better than talking to my mama, though. She had called earlier this evening to bug me about coming home for the holidays.

“Meet any interesting men today?” she had asked. That’s all Mama cares to know, and that’s how every conversation starts.

“No, Mama.” Though there’s this homeless man who winks at me all the time. He’s a nice man, I’m sure, but he only comes into the library to bathe in the men’s room sink and dry his wet socks with the hand dryers.

“Well, you remember what I’ve always told you, Dee-Dee.” That’s what my mama calls me, and I hate it. “You can have any shade of a man as long as he’s black.”

She has a million sayings just like that one. I should write them all down and call the book Things My Mama Says That Make Absolutely No Kind of Sense to Anyone But Her. The title would barely fit on the cover, leaving only a little room for my full name: Diane Denise “Dee-Dee” “Nisi” Anderson.

And though I tell her that Roanoke is 30 percent black, she’s convinced I’m living in Caucasian-land.

“I’m more open-minded than that, Mama,” I had told her, though I’m not as open-minded as I want to be. Roanoke is, well, Southern, despite its location on the map just east of West Virginia. Folks frown on mixing salt and pepper people around here.

“As long as you have a black man up in there in that open mind, I don’t care.”

“That’s not what having an open mind is all about, Mama.”

“It isn’t?”

“No.”

“It is to me.”

But you’re wrong! I had wanted to shout. “Mama, that’s not it at all.”

“Well, you tell me what you think having an open mind is all about.”

“Okay, you see, you have to be willing to accept anyone into your life, regardless of race. That was what Maya Angelou was all about. That was what Dr. King was saying when—”

“Don’t you bring Dr. King into it!”

Mama has had some, well, issues about Dr. King ever since she found out he wasn’t faithful to his wife. We can’t talk about Bill Cosby, Magic Johnson, or Jesse Jackson anymore either. Oh, and Kobe Bryant, too, but I mentioned Kobe once, and all Mama said was, “Those Asians took over baseball, and now they’re taking over the NBA.” My mama, who lives in basketball-hysterical Indiana, knows next to nothing about Hoosier Hysteria or the Pacers.

“Mama, you know what I look like.”

“I look at your picture all the time, and it’s like looking in a mirror.”

Not. I’ve got Daddy’s skinny face, which doesn’t quite fit the rest of my…let’s say healthy, twenty-five-year-old body, and though Mama’s body only jumps out in front (Mama’s got a bad case of “no ass at all”), my body jumps out only in back. I’m not flat in front. I’m just not “well-rounded.”

“Mama, I’m plain.” With a train. A caboose. And though I walk the stacks at least half of the time I work, I will never be able to uncouple that caboose.

“As soon as you have a husband and a baby, you’ll get some titties to match your behind.”

And Mama’s a churchwoman. Forty-three years she’s been a member of her church, and she’s the only woman I know who says “titties” like it’s any other word like “chair” or “kitchen.” She even points out other women’s chests sometimes, saying, “That woman over there has some tig ol’ bitties”—as if anyone listening can’t figure out what she really means.

Yeah, she embarrasses me sometimes.

“Mama, come on. I’m too plain for any decent-looking black man to notice me.” Not that I’ve been trying, and not that any decent-looking black men ever come into the library just to meet me. “But I’ve got just enough…exoticness”—is that even a word?—“to attract any—”

“Don’t you say ‘white man,’ because you know I won’t have that. Not since that Bobby and you in the seventh grade.”

Which was thirteen years ago. It was my first sock hop, an in-school dance, you know, all sweaty palms, red hair bows, not enough lotion on my elbows and knees, and Bobby, who was plain and quiet like me was the only one to ask me to dance, and I really wanted to dance, so…I danced with him. That was it. One dance to some old El De-barge song, something like “Love Me in a Special Way.” Our hands kept slipping off each other because of the sweat, and neither of us looked the other in the eye. He had an ashy nose. Not that I remember much about it—

Okay, it was a turning point in my life. I can’t deny it.

There I was, plain, flat as a board, just brown enough to be called black, the beginnings of my caboose slowing me down, and I was totally ignored by every black boy in the gym because I didn’t have titties. Or a weave. Or make-up. Or fingernails. Or bicycle shorts. What was that all about anyway? Hey, everybody, look at the veins in my butt! And the only boy in the room who consciously made a decision to think I was good enough for him was a white boy named Bobby. I wonder where Bobby is now. I hope he’s not a doctor with those sweaty hands of his.

“Mama, that was so long ago.”

“I remember it as if it were yesterday,” Mama had said. “The shame of it all. Getting told on Easter Sunday by Imogene Blakeney, of all people, that my youngest daughter was bumping and grinding with a white boy in plain view in public. It was a shame.”

“We weren’t bumpin’ and grindin’, Mama.” I’m starting to drop all my gs whenever I talk, and I’ve only been in Roanoke for a year. I refuse, however, to use the phrases “might could” or “How you doin’?”

Mama had growled. “Like I said then, and I’ll say it to you now. You should have danced by yourself before you danced with any white boy any time, any place.”

And that’s what I’ve been doing ever since. I’ve been dancing with myself. It isn’t so bad. I’m on my own, have my own place, my own car, my own bills, and my own savings and checking accounts. The only time it isn’t fun being independent is late at night, especially if there aren’t any C batteries in the house.

And Mama will never know about any of that.

Her Baptist heart couldn’t take it. The shame of that. She’d probably find out right before another Easter service or something, and Mrs. Imogene “Couldn’t-Hit-a-Note-if-You-Hit-Her-with-a-Hammer” Blakeney would be screeching it all over the sanctuary. I know Mama has only gotten her “pleasuring,” as she calls it, from Daddy, my uniquely handsome, skinny-faced, shovel-handed, wide-footed, gap-toothed Daddy. They make a cute couple, but I doubt Daddy would ever buy Mama C batteries for anything but a flashlight.

“Now your sister…”

As soon as Mama had mentioned Reesie, I had tuned her completely out. Reesie is my older, supposedly wiser, African sister, who has only made babies (three and counting) with African boys since she was fifteen. And Mama never had any shame about any of that. None at all. I danced vertically with a white boy once, and Mama was ashamed. Reesie has danced horizontally with three different black boys, and Mama’s proud as she can be.

If that isn’t dysfunctional and worthy of an entire segment of Oprah, I don’t know what is.

And Reesie, who I have no respect left for, once told me, “They found you by the side of the road, Nisi.” After Mama had straightened that lie out, Reesie told me, “They were gonna adopt a puppy, and they adopted you instead.” I have too much of Daddy in my face to be adopted, but sometimes I wonder if they switched my mama at birth or something.

“Are you listening to me?”

“Yes, Mama.” I had yawned. “I have to go.”

“Go where?”

“Out, Mama.” As in, out of the living room to the kitchen to get a slice of orange cake left over from the library Christmas party.

She had sighed. “I still don’t know why you had to move so far away.”

“Roanoke is where my job is, Mama.” And Indianapolis is many blissful hours away. Luckily, Roanoke isn’t connected nonstop by air to any city except Pittsburgh, Charlotte, and D.C.

“And why did you have to have your own place, and a whole house at that, and not even in a black neighborhood?”

“There are plenty of black people in my neighborhood. The family across the street and the neighbors to my right—”

“They aren’t really black if they live where you live.”

No, I had wanted to say, they’re just middle class enough to live here and just happened to be able to scrape up enough money for a down payment so they don’t have to live on top of other people in an apartment complex.

“Child, you could still be living in your own room right here in this house, you wouldn’t have a mortgage, and that city library you said you liked working at the most is just around the corner.”

That particular city library in Naptown was the first to turn me down for a full-time job after graduation, but I purposely screwed up the interview. I didn’t want to be working a stone’s throw from my mama! I might have picked up those stones and thrown them at her! It did, however, offer me part-time work at minimum wage; I accepted…and I endured three dreary years with Mama and Reesie’s three little monsters I collectively called “the Qwans”: J-Qwan, Ray-Qwan, and Qwanasia. If it weren’t for Daddy, I would have gone out of my mind.

“Mama, they didn’t want me for the position I deserved four years ago.”

“Well, there are plenty of other libraries around here, and maybe they have some openings now—”

“Look,” I had interrupted, “I’m blooming where God planted me, okay?” Mention “God” to Mama, and she at least takes a breath. “Staying and working the stacks in Indian-no-place at minimum wage was a waste of my time, Mama, and—”

“Excuse me?” she had interrupted. “Living with me and your daddy was a waste of time?”

“That’s not what I said.”

“It sounded like you said it to me.”

My mama only hears what she wants to hear. “I said that the job was a waste of my time. It was a waste of my degree and all that money you and Daddy paid for me to go to college. Look, Mama, I’m tired. I’ll talk to you later.” Then I had waited for her to get the final word.

And this time, Mama didn’t speak right away. That gave me time to walk down my hallway, clutching a cordless phone I paid way too much for, wearing an outfit I bought with my own money at regular price at a store Mama would never shop in, into my library. Yes, I have a library. What else do you do with a three-bedroom ranch (advertised as a “handyman special”) when you only need one bedroom? I know it’s redundant and stereotypical for a librarian to have her own library. But I’d much rather buy books and shelves than beds no one will ever sleep in. If Mama and Daddy threaten to visit someday, I may have to buy a sleeper sofa or something. I’ll probably end up just sleeping on that sofa since I’m leaving the other bedroom “fallow.” It’s my storage room now.

But I don’t want to think about that. Not the buying of the sofa—the visit from Mama and all her criticisms. She’ll look at my house as her house and spend the entire visit “fixing” everything I’ve done wrong.

“You make sure to be in church on Sunday,” Mama had said eventually. “Maybe you’ll meet somebody.”

Just once, I’d like to go to church only to meet Jesus. “Good night, Mama.”

“And go to a black church this time, Dee-Dee, okay?”

Click.

Oops. I had hung up on my mama. I had only been thinking about hanging up on her, and my finger had hit the button before I could stop it. The phone had rung a second later. “Sorry about that, Mama. My finger slipped and I—”

“Are you coming up for a visit or not? At least come up for New Year’s.”

I had taken a deep breath and closed my eyes. “No, Mama. As I’ve told you before, I have—”

“Your own life now. I know, I know.” Silence.

“And I only have one day of vacation left this year.” More silence. “I promise to come home for Thanksgiving.”

“Thanksgiving? That’s in…eleven months!”

“Bye, Mama.”

Click.

I had waited a few minutes, and the phone didn’t ring. After that, I had started shuffling cards and…here I am.

I really shouldn’t be playing solitaire at all. I should be making cookies for Santa, which only I would eat in the morning. I should be wrapping gifts (mainly for myself) or listening to carols or even looking out the window for the snow showers they’re predicting. Roanoke might have a white Christmas for the first time in anyone’s memory. But aren’t all Christmases white anyway? You have a white Jesus, white shepherds, white angels, and white stars. It’s a Caucasian Christmas. At the library, we’ve been listening to a country station that plays only Christmas music from Thanksgiving to New Year’s Day. Our library isn’t completely quiet, because Kim “Prim” Cambridge, the library director says, “We have to compete with the mall, and they’re playing that music, too.”

Kim is…odd.

So, I’ve been subjected to eight hours of “Jingle Bell Rock,” “Silent Night,” “White Christmas,” and “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” Oh, and “The Christmas Song” sung by some white guy with a twangy voice. Where are Nat King and Natalie Cole? Or just Nat? Mmm. I could get used to Nat’s creamy-butter voice in my life. I doubt I’ll hear him on that station, though I did hear a little Luther Vandross one day. It surprised me so much when he belted out “O Holy Night” that I did a little chair dance right there at the reference desk.

Francine, the other Grade Four Clerk, had then had the nerve to ask if I needed some lotion for my behind. “You look all itchy and twitchy,” she had said.

White folks just don’t know a good chair dance when they see one.

I was listening to that station earlier tonight, but I’m all Christmased out. Those reindeer keep hitting grandma—because grandma is drunk—and the little drummer boy (all seventeen different versions, three every half hour) is giving me a headache with all that rum-pum-pum-pumming. I’m no Scrooge, but when you start hating “The First Noel”—the first Christmas song I learned to sing when I was five years old—you don’t have any Christmas spirit left.

I look at the gifts under my Charlie Brown Christmas tree, a remnant of a tree I actually bought at a Christmas tree lot. “Topped it off a real big one,” the man had told me, and I had talked him down to three dollars.

You know you’re horrible at celebrating Christmas when you talk a man down to three dollars for the top of a “real big one” and your tree fits in the front passenger seat of your Hyundai.

And, you know you’re lonely when there are only four gifts under that tree. Two are from anonymous coworkers (one from a gift exchange with the circulation staff, one from a gift exchange with the reference staff), and both are books: The Da Vinci Code and The Handmaid’s Tale. Neither book is my cup of tea, but they’ll look nice in my library. The third gift is a sweater I bought for myself at Lane Bryant. I had tried on several sweaters ranging from sizes ten to eighteen, and though my heart had said, “Give yourself a size ten, girl,” and my mind had said, “You’ll look just fine in a fourteen,” my body ordered me to wrap up the size eighteen. It actually fits me better, though I’m embarrassed that it fits me better. It will give me an excuse to get out after Christmas to exchange it…for a sixteen…or a fourteen, who knows? I may take a couple walks around the block tomorrow.

And the last gift really isn’t a gift at all. They’re books I get to review for the Mid-Atlantic Book Review, an on-line book club I’ve belonged to since I arrived in Roanoke. “We’re MAB, and we’re Mad about Books!” is our slogan. I didn’t make the slogan, and, for the most part, I’m “Mad at Books.” The trifling stuff they publish these days…At least these books will keep me busy for a week or so.

Until then, I’ll just—

“Finally!”

Now if I can only find a red jack, I’ll be…

Set.

Time to shuffle.

Again.

Merry Christmas, girl.