Читать книгу For Love of the Dollar - J.M. Servin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

LIVING THE DREAM

BY DAVID LIDA

There are two prevalent narratives about undocumented Mexicans in the U.S. The first is a tale of hardship, sorrow, and danger—the story of the struggle of people on the fringes of towns and cities, unable to enjoy the rights and privileges of citizens; of endless days of monotonous work that nationals won’t do any longer: landscaping, housekeeping, construction, scrubbing pots and pans, meat-packing.

The counter-narrative, repeated frequently by politicians and writers of pot-boiling thrillers about the drug trade, paints Mexicans without papers as cold-blooded criminals, “bad hombres,” and “rapists,” people who, if you so much as stand in their way, will shoot you between the eyes before tucking into a plate of enchiladas rojas.

However one-sided, there is a basic truth to both of these stories: The undocumented come from Mexico’s most struggling social class. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be undocumented. Immigration authorities have no problem issuing visas to Mexico’s wealthiest citizens, but few of them have any desire to live in Gringolandia. Mexico’s aristocrats stay away from the U.S. once they’ve earned their MBAs or other post-graduate degrees at Harvard or Stanford. After their commencement ceremonies, they prefer to return to Mexico, and plum jobs either in government, the private sector, or the family business, where on similar salaries to what they’d be earning in the U.S., scandalously cheap labor allows them to hire cooks, gardeners, maids and chauffeurs. I remember from the early 1990s a Mexican who referred to a gringo counterpart with a mix of contempt and disbelief: “He earns a hundred and fifty thousand dollars a year, and he mows his own lawn.” This Mexican would travel to the U.S., but only to accompany his wife on trips to shopping malls in Houston and San Antonio.

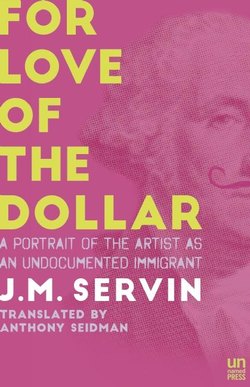

J.M. Servín, author of For Love of the Dollar, is in a class by himself — at least as far as the literature of the undocumented is concerned. He is from the Mexican middle class. A little definition is in order. The term “middle class” in Mexico has nothing to do with what those same words mean in the U.S. (or at least nothing to do with what they used to mean before the economic crisis of 2008, when people in the U.S., whose salaries had been stagnating for twenty years, began to see an entire way of life disappear). The Mexican middle class, unlike the Mexican poor, does not struggle from day to day to put food in its mouth, but it definitely goes into panic mode at the end of each month when the bills are due. It is a social class that subsists on what would be considered slave wages in the U.S., and has few of the social benefits that middle-class people north of the border have traditionally taken for granted.

It’s a social class that has been hammered by peso devaluations that have occurred consistently since the 1970s. When Servín was born, in 1962, the peso held steady at 12.5 to the dollar, and would continue to do so until 1976, when overnight it went to 22 to the dollar. By the early 1990s, it was at 3,400 to the dollar, before the president tried to “fix” the problem by lopping off three zeroes at the end of the currency.

Throughout these years, the elite and the impoverished tended to live more or less as they had throughout Mexican history, but the middle class struggled to keep afloat, when the falling oil prices, high inflation, no credit and rising interest rates became Sisyphean. Through much of the 1980s, Mexico’s GDP grew at the rate of less than one percent per year, while inflation galloped at 100 percent annually. Many middle-class Mexicans who worked in both the private and public sectors lost their jobs, and began to emigrate to the U.S. by the thousands, to work in agriculture, construction, or maintenance. (One of these Mexicans was Servín’s father, who found work supervising a jewelry workshop in Rosenberg, Texas.) Many of those who stayed behind resorted to work in the informal economy—parking cars, cleaning houses, or selling cigarettes and chewing gum at traffic intersections (when they weren’t cleaning windshields or eating fire). These days, more than half of Mexico City earns its living informally. Servín came of age in the beginning of the 1980s, the start of what would become known to many in Mexico as “the lost decade.”

“My parents could name all the pawnshops,” Servín writes in For Love of the Dollar. “They transmitted their experiences to us as if by osmosis. ‘Property should be used to get you out of sticky situations’ was the family motto. My mother’s children grew used to living on the installment plan. Filling our stomachs was the priority.”

In the early 1990s, Servín went to New York on a tourist visa, which gave him permission to stay in the U.S. for a few months. He would remain there for seven years, minus a short stay in Ireland for what was essentially a drunken spree. For Love of the Dollar is a chronicle of those years, in which Servín did his best to ignore the prevalent social stereotypes of hangdog laborer or bloodthirsty drug dealer. Instead, he was inspired by some of his literary heroes, such as Louis-Ferdinand Céline, whose experiences as a young man in Africa, Cuba and the United States (sometimes on medical missions for the League of Nations), shaped the novels he would write later in life. Or Nelson Algren, who came of age just as the 1929 stock market crash sent the world into the tailspin of the Great Depression—and who spent some years hopping freights around the U.S. (and did time in jail for stealing a typewriter) before publishing his first book.

In contrast to the prevailing narratives, For Love of the Dollar is a picaresque; a tale of adventure and misadventure, as Servín wends his way through the Tri-state area. He finds work in the kitchen of a restaurant in midtown Manhattan (but not before spending a hundred and twenty dollars to acquire a false Social Security number, in order to have the privilege of paying taxes on the six dollars an hour he earns). He graduates to being a “nanny” for the rich brats of a suburban family, where he helps himself to the liquor cabinet when no one is looking. He also mows the lawns in an elite golf club, and culminates his stay in the U.S. with a job pumping gas at a Mobil station in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Throughout, Servín is skeptical, and at times downright contemptuous, of his compatriots (including one who kisses a crucifix around his neck each time someone gives him a dollar tip for cleaning a windshield). He writes:

The day laborers were never too interested in learning English; they would let their bosses speak to them in choppy, rude Spanish or through interpreters. Sometimes they wanted to learn, but they couldn’t; at other times, they could, but there was always something better to do than go to classes...Sooner or later, the law of minimal effort would prevail. Single men would live crowded together in guesthouses or small rooms that were sometimes the property of their bosses. When they weren’t working, they bummed around the house, lazing away the day. The most obsessive ones saved up (or ostentatious used cars, luxury items, electrical apparatuses, or transactions with a coyote...They would return to their countries each winter, and they would return each spring to seasonal jobs, without money and with hangovers that would last until summer. They would complain, but the dollar’s an addiction.

Unlike them, Servín revels in his status as an immigrant in the shadows of his adopted country, living his version of the American Dream: listening to James Brown records and spending every cent he earns in dive bars, or on flasks of whiskey and grams of cocaine to keep him warm on winter nights in the gas station, or feeling up strippers in peep-show booths in Times Square (just before that part of New York was transformed into Disneyland). His quest for love and sex most often ends in mishaps along the lines of a low-rent Henry Miller, in encounters with prostitutes, adulterous wives, or waking up in a pool of vomit alongside other undocumented Mexicans.

I’m not saying that Servín is the only Mexican who ever crossed the border on a joyride. But as far as I know, he’s the only one who ever wrote a book about it. With a mordant eye, he never loses sight of his social status and the Faustian bargain the undocumented make along with their dollars. They were:

...black and Latino workers, undesirable renters, but ready to live by the highway and the interstate in a gloomy neighborhood surrounded by factories, warehouses, gas stations, and waste processing plants that attracted opossum, squirrels, and skunks. The streets were rarely traversed at night and, if so, only by people passing through and looking for drugs in the nearby ghettos, all located next to the train station. Our awareness that we lived in poor neighborhoods was consoled by the fact that the power and water always ran, the streets were paved, and that problems were taken care of quickly. The landlords asked for two months’ rent in advance, for our work phone numbers, and that we try to minimize our accents. As a “favor,” they wouldn’t run the credit on the Social Security number on the copy of our bank statement.

Much has changed in the twenty or so years since Servín left the U.S. and returned to Mexico. But some things stay the same ad infinitum. Since the 1970s, U.S. politicians, talking out of one side of their mouths, have spoken in accusing and censorious terms of the “immigrant problem” in the U.S., while at the same time, out of the other side, exploiting those same immigrants’ willingness to work for low wages in their communities (and pay taxes, sometimes at a higher rate than the wealthy in those same communities). Now that the U.S. has elected a president whose political platform was primarily a screed against the undocumented, perhaps before long we will regard For Love of the Dollar as a sentimental document, some nostalgie de la boue from more carefree times.

David Lida

Mexico City, 2017