Читать книгу A New Tense - Jo Day - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

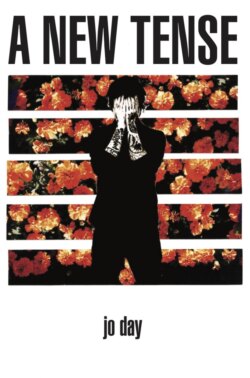

The Jones'

ОглавлениеI only had my carry-on luggage, a big old army backpack, and I passed quickly through customs at Melbourne Airport, I was one of the first people out. The hangover I so deserved had finally kicked in and I was so tired and hungry that I felt faint. As I came out into the international arrival lounge they were there immediately, Calliope and Gary and Jones, and I had to stop myself from double-taking at Jones because he was gaunt, cheeks pulled in, singlet hanging off scrappy shoulders that’d always been so strong.

I went over to them and greetings were said. Calliope put her arms around me in a hug and it was too much. I was covered in cold sweat, my heart was pounding, and spit was pooling in my mouth. I was suddenly aware that I was going to throw up. I looked around for the nearest toilets but couldn’t see any, a bin was the closest thing to me. I mumbled something like an apology to all of them before I went over to it and vomited.

Not much came out of me and thick bile burned the back of my throat. Someone was behind me, rubbing my back. It was Calliope. Good old Calliope. If I had enough hair I’m sure that she’d have held it back from my face.

After a few minutes it subsided, my heart went back to its normal rhythm, but there was still something wrong. I felt disconnected and I couldn’t talk, all my words were coming out strangely. Jones looked worried. He took my bag and didn’t ask me questions, and when I staggered a little coming off the escalator he took my arm and linked it through his, supporting me.

In the car they took pity on me and stopped trying to involve me in the conversation. I sat with my legs drawn up, looked out of the window with hot air blowing into my face, which felt burned despite not having been in sunlight for weeks.

I barely remembered going inside the house but I woke up sometime later in the bedroom that had once been mine. I went out into the kitchen. Jones was in there, sitting at the kitchen table with his laptop open, drinking a beer, and I was so disorientated, was I really on the other side of the world?

“Hey,” he said when he saw me. He closed his laptop. “How’re you feeling?”

“Yeah, better. I’m so hungry though, is there anything to eat?”

“Yeah, there’s a bunch of stuff, mum made it for you.”

“How long was I asleep for?”

He looked at the clock on the wall. “Seven hours.”

“Seriously?”

“Yup.”

“Right. Where are Gary and Calliope?”

“They’re at some family thing.”

I went to the fridge and pulled out all the containers. Beans in tomato sauce, a bunch of different salads, skordalia, spanakopita. I’d forgotten how good the food was here, Calliope went to her parents’ house a lot and cooked big meals, or her parents did alone and delivered them to her. There were beers in the fridge, too. I balanced a bunch of containers on the counter and popped the cap from the beer, drank greedily. It felt small in my hands compared to the longnecks I was used to and I necked half of it in a mouthful. I couldn’t be bothered plating up the food, and ate it straight from the containers, oily beans and fresh vegetables. Jones had opened his laptop again.

Around a mouthful of spanakopita, I said, “Are you working on something?”

“Yeah. But I won’t bore you.”

“It’s okay, I’m used to it. Go on.”

“It’s just some coding for a company.”

“Okay.”

After I’d eaten and put everything away we smoked cigarettes in the backyard, Champion Ruby for him, Pepe for me. He bought out speakers and played some music.

“Are you playing the drums anymore?”

“I’m practising, but I’m not in any bands right now.”

“How come?”

“I don’t feel like it.”

“Okay,” I said again, even though I had a million questions.

“How’re you feeling?”

I considered. “Yeah, alright. Tired and jet-lagged but okay.”

He lit another cigarette. “Have you decided if you’re going to the funeral or not?”

“I dunno. When is it?”

“Day after tomorrow.”

“Right. Fuck. Um...I guess I’ll decide tomorrow.”

“Fair enough.”

A silence stretched between us. “So what’s happening with you, man, are you living here?”

“Yeah,” he said slowly. “For a little while.”

“Fuck.” I’d have asked what was wrong if I thought there was any chance that he’d answer me.

“Do you want to see the paper?”

“The paper?”

“There was an obituary in the paper today. I saved it in case you wanted to see it.”

I breathed deep. The air was warm and rich with jasmine. Somewhere on the street a family was having a barbecue, I could smell the smoke and hear voices from a backyard nearby.

“Yeah, okay.”

He went inside, sliding the door behind him. I stretched my arms up, trying to fix the knots in my back from the plane, even though it felt like the whole trip hadn’t happened, that I’d been in Berlin a second ago. Jones came back with beers for the two of us and handed me a newspaper, folded open at the obituaries page.

Turnbull, Madeline Jessica.

Beloved mother, and partner of Mark.

Funeral and memorial service will be held at

- and it gave the details of a church in St Kilda. Beloved mother? Who wrote that?

“So did you talk to this guy? To Mark?”

“Yeah.”

“What’d he sound like?”

He shrugged. “Just a guy. Pretty sad.”

I pictured some kind of English Victorian, waistcoat and all. I wondered how they’d met, if she’d gone on dates, what they’d have done. If they’d had a first kiss, if they’d held hands. Beloved mother. “He left his number, he said that you could call him.” He drew on his cigarette and exhaled quickly, the way he always smoked, little mannerisms that I’d already forgotten about. “Oh. Right.” I looked at the number. Put the paper in my pocket. “Fuck it, I’m not doing it today.” I sighed deeply and realised that I was beyond the point of reeking, and I hadn’t changed my underwear in days. “I’m gonna have a shower, I stink.” I was digging around in the pockets of the jeans I’d been wearing on the plane, trying to find a hair tie, when my fingers brushed against the unmistakeable thickness of a baggie. I was home and safe and through god knows how many airport securities, and here it was, not much, a few big lines of speed, but still my heart stopped in my chest for a moment and then, when I put a hand to my chest to remind it to do its job, it compensated by going double its normal rate. “Jesus fucking Christ,” I said, to no one. I sat on the edge of the bed, holding the baggie in front of me. “Shit,” I said, as I was tapping out a little line, just a little one, on the bedside table, rolling up a five dollar note from my wallet. The familiar burn. The shower was luxurious. My apartment in Neukölln was old and charming but the water pressure was ridiculous, just a trickle, Steffi came out of it looking fresh but I came out with soap still in my pit hair. This, though, this was blasting, and I was gasping with the pleasure of it. I got out. There was a full-length mirror on the opposite wall to the shower. I unwrapped the towel and took it in, body going so from the winter and belly protruding from the beers but still a strong body, and if it wasn’t conventionally beautiful it was beautiful in its abilities, there was strength underneath the so ness. The first time I’d taken all my clothes off around a woman — or a girl, we’d both been girls — had been fast, all of them off at once. I was saying here it is. Expecting disgust or laughter. Instead, she’d sat up in bed and smiled at me and pulled me down on top of her. I liberated one of Calliope’s hair ties, smoothed my hair from my face, and went into ‘my’ room. I put on fresh underwear and cut-offs that hadn’t been worn since summer. I hadn’t had any clean shirts to pack and now I didn’t want to wear anything that smelled of sweat. I walked to the kitchen in my bra and shorts, called outside. “Hey, can I borrow one of your shirts?” “Yeah, go nuts,” Jones said. He’d been looking at his phone, he put it face down on the table. “They’re in my room.” Everything was crisp but deliciously off-kilter. Jones’ room smelled of cigarette smoke and there was an empty Vegemite jar full of butts next to the window. I opened a beat-up duffle bag on the floor, expecting Jones’ usual jumble of mess, but it was empty except for a few leftovers — an odd sock, a ripped flyer of a band I didn’t know. His general mess was in his cupboard. I picked out a black t-shirt, soft and clean, and pulled it on. Looked in the mirror, inspected my smile again, seeing how far I could go before I revealed the gap. I helped myself to his deodorant and then looked around at the room again. There was a notebook on the bed. I picked it up, just to hold it, and then put it back. My heart was racing a bit and I wanted a cigarette. I went back outside and lit one and started to talk about a band I’d seen, a feminist band from Sweden that I’d seen last week in Prenzlauer Berg, how when me and Julia had talked to them afterwards they’d said we should go visit them and play some shows and we could stay at their place, they all lived together and I was envisioning some blissed-out commune. Probably it was just drunk talk — our band wasn’t so good yet, we were just starting, but still, it was exciting. Halfway through I realised that Jones hadn’t asked me any kind of questions, I’d just come out and started to talk about it, and I was talking too fast. When I stopped for breath he smiled. “So how’s the jet lag?” “Yeah, I’m fucked.” Ordinarily I’d have told him about the speed, offered him some, but it still felt a little weird between us, and there was a self-awareness of the fact that I was taking speed just to sit here, and I would’ve had to admit that I’d brought it all the way with me, accident or not. “No arguments here.” I couldn’t stop myself from smiling. “What?” “It’s just... it’s fucking amazing to see you, man. I’ve really missed you.” “I’ve missed you too,” he said. We kept drinking. Jones played more and more music but none of the stuff that we ever listened to together. We didn’t talk about Pete. I guessed I couldn’t blame him, he’d been through the same, or nearly the same because Jones hadn’t found him. But I couldn’t bring it up. I couldn’t imagine his reaction if I told him that the world was still fucked for me, not all the time, but sometimes when I lay in bed trying to sleep after a good night out Pete’s face would come to me and I’d crawl into bed with Julia, and if she wasn’t home or had someone over then I’d drink in bed until I could cry or pass out, or both. And that wasn’t fair, anyway. It was impossible to know how Jones felt, and I didn’t really know what it was that I wanted to talk to him about. Mostly I didn’t know how to voice the feeling that I was arriving at something, some surety, but I didn’t know of what. Maybe acceptance, I sometimes thought, and I thought as well that I was avoiding that as much as I possibly could because that idea was so much worse than any pain. The speed made me sound nasal, made me sniff every few minutes. Jones had his bare feet on the chair, was smoking cigarette after cigarette. I went to the bathroom to piss and have another line. It was still early, or early enough to have more beers and see if Jones had some weed to smoke before crawling into the clean bed. A nice lie-in tomorrow. I walked down the corridor. I was a bit drunk, I had to trace a hand along the wall as I walked, and as I did my arm brushed a photograph and nearly knocked it down. I righted it, swaying slightly. The house was covered in photos of Jones as a kid, looking at the camera, masses of curly hair, so fucking beautiful that I imagined his whole childhood had been plagued by old women in supermarkets pinching his cheeks until blood vessels were at risk of bursting. I went back outside. I was getting more and more in my head, trying to be conscious of the conversation and be quick in my responses but even with the speed I felt slow. We talked more about music, and this led onto music in video games, which led to the intricacies of a game he was making, and I was proud of him but as usual I started to drift. I was looking at him but my mind was floating away, thinking of photos I should get printed out, drawings I could do, a show I could play, friends I should get in contact with. Gemma, Ryan, Scotty, Holly. And Ada — I missed Ada. I’d only met her a few years ago but it’d felt like I’d known her forever, so that we talked about experiences we’d had when we were kids as though the other had been there. “I’ve completely lost you, haven’t I?” I came back, shook my head. It was dark, the night light had flicked on. Moths and other bugs were bashing into it. “Yeah, completely, I was totally in my head. Go on, tell it again, I’ll try to listen.” “It’s alright,” he said, smiling. “You can just play it when it’s done.” “Thanks,” I said gratefully. He’d always been into video games, since I’d first known him. The first time I went to his house he’d made fun of me, telling me I was no fun to play against because I was so bad. I didn’t really know what a video game was — mum didn’t have a television or a computer or a mobile for years, which could’ve been great. Like I’d be trampling through the wilderness, or something, when what I was really doing was taking my skateboard down to the skate park and sitting with the older boys, drinking their beer and smoking the weed they gave me as a joke, imitating their machismo. One of the boys, they called me for a while, and I wore this title with pride before I started to realise that they were excusing me from something that didn’t need excusing. So when I went to Jones’ and saw the television and the console I had no idea what I was doing. When he realised that I was confused and getting embarrassed and angry at his comments he’d backed off, had said, It’s okay, you play for a while, I’ll teach you. I can’t believe you get to play for the first time. The first times, man, those are the best. “And you,” he said, lighting a cigarette. “What have you been doing?” I told him the outline. Working a little, playing a lot, boozy nights out and boozy nights in. Making zines. Odd jobs I’d gotten, people I’d met. “I’m in a band with one of my housemates,” I said. “We’re not bad.” “Oh yeah? That’s cool.” I couldn’t tell but I thought that I heard a tone of caution in his voice. Jones and I had played together for a while, growing up. He played drums, he said if you understood maths it was easy. I wasn’t sure that I believed that but it seemed to work for him. I bought myself a shitty bass and amp with one of my first pay checks and we started to play together. We started playing with Pete when he moved in. He played guitar, he’d been in a few bands in England, some folk-punk stuff we hadn’t heard of before, which I’d liked but Jones hadn’t. We got better because of Pete. Jones and I had been lazy with practice, preferring instead to get drunk, but Pete wouldn’t have that. He introduced us to bands we hadn’t heard of before. We all sang even though none of us had good voices. Jones’ was monotonous, Pete’s wavered in and out of tune. I could sing but I hated the girlish sound of it (it took me the longest time to stop hating anything feminine, one of the boys rang so often in my head) so I forced it to sound guttural. After I’d started to get horrible sore throats I went to see a doctor. He told me that I was starting to get nodules and said, trying to be helpful, Well, you should probably learn how to sing. Pete would stand in between Jones and the game on the television (the most dangerous place in the world) and wouldn’t say anything but would just look at him, chin tilted down and eyebrows raised, refusing to move until Jones, grumbling, would put the controller down and we’d go practice. We had a few shows, supporting other bands, and we got good feedback. “Maybe we could play together sometime,” I said. He shook his head. I thought he was going to say something — I wasn’t sure what — but he just stood up. “Do you want another beer?” “Sure.” I reached for my tobacco, saw that it was empty and reached for Jones’ instead. Lifted my arms to stretch my back and looked at the plants on the patio, ferns and potted palms in terracotta pots. One that I’d bought for Calliope for her fiftieth birthday. It needed watering.