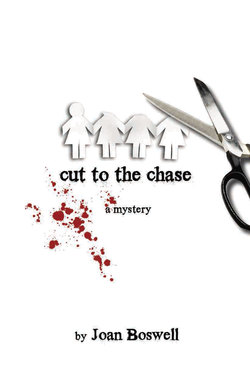

Читать книгу Cut to the Chase - Joan Boswell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One

ОглавлениеBrush in hand, red-framed glasses perched on her nose, Hollis Grant studied the large canvas positioned on the easel set under the north-facing skylight. Earlier she’d cranked the window open to allow Toronto’s unseasonably warm late October air to flow into the room. The third floor attic apartment remained hot, but she ignored the heat, focused on her work and tried for the moment to ignore her concern for her landlady and friend, Candace Lafleur.

She intended to create a golden puzzle, a painting that would draw the viewer in and make them search for meaning. There would be tones and textures of gold with half-revealed hidden messages. Except for the reference to gold, this description could refer to Candace. For the past week, Candace had been a women obsessed with a problem but unwilling to share the details.

The painting wasn’t working. Damn.

She plunged the brush into the water on the tambour beside the easel. She felt like pulling out her hair. She momentarily envisaged herself bald as an egg and the floor littered with curly blonde hair.

What if she couldn’t fix the painting? Couldn’t paint what she visualized? Couldn’t succeed as an artist? These depressing thoughts sidling into her mind frightened her.

Not again. She’d suffered bouts of depression in the past, and they’d immobilized her. Bad enough to have painter’s block—she couldn’t allow depression to overwhelm her.

Exercise—that would help, she decided.

Several years earlier, her soon-to-be ex-husband had challenged her to take up running to lose weight and improve her fitness. Surprisingly, once she’d accomplished these goals, she hadn’t given up running; the process and the joy it produced had hooked her. Another plus had been its slimming effect on her slightly corpulent golden retriever, MacTee. They’d become committed runners, although sometimes, when she found herself plowing along in snow or rain, she wondered if “committed” wasn’t exactly the right word.

Today, probably one of the last warm autumn days, instead of running, she’d sit in the garden, enjoy the sun and read the Saturday paper. Maybe she’d solve the cryptic puzzle; that always boosted her ego. Entertaining diversions also helped to chase away the black dogs of depression.

She opened the fire escape door which overlooked the garden, noting that the latch needed to be repaired. Paper tucked under her arm and a thermos of coffee clutched in her hand, she enjoyed the view over the neighbourhood before she cautiously descended. As always, the rusty railing alarmed her. She chose not to touch it but to edge her way down, allowing her free hand to touch the wall. MacTee, nervous about the see-through stairs, hesitated for a long moment before he reluctantly followed.

On terra firma, she breathed deeply and stared up at the intense blue autumn sky. They’d had a cold snap and a few flakes of snow earlier in the week. Today the temperature hovered at twenty, and the radio weather reporter had promised this warm weather would last through Hallowe’en, the following Tuesday. Great for the kids who wouldn’t have to wear parkas and snow pants under their costumes.

She dropped the newspaper on the round cedar picnic table, retrieved a sling-back canvas deck chair from the garage, unfolded it and prepared to relax for an hour and think of anything but painting or Candace. As she sorted through the sections, deciding which to read first, MacTee, after rolling ecstatically on the leaf-covered grass, flopped down, groaned with pleasure and stretched out in the sparse shade of a maple almost devoid of leaves.

The ground floor door banged open.

Hollis, halfway through reading editorial speculations about an unidentified mutilated murdered man and his possible connection to the murders of male drug users in the downtown core, lifted her head. Candace emerged, leading two-year-old Elizabeth and carrying newspaper and coffee mug.

“Good morning. Hope you don’t mind company,” she said, releasing the toddler’s hand. She spoke in a flat tone.

Whatever had been bothering Candace was still affecting her. She’d been tense and nervous each time Hollis had spoken to her during the week. She wasn’t likely to be very good company, and certainly she looked anything but peaceful. What could Hollis say? The yard belonged to Candace who allowed Hollis and MacTee to use it.

Elizabeth, wispy blonde curls escaping from her pink baseball cap, chortled when she spied the dog. Clad in overalls and a pink windbreaker, she toddled toward him shouting, “Tee, Tee, Tee.”

MacTee adored children and tolerated their unintended abuse. He always allowed Elizabeth to catch him, grab great handfuls of hair and hug him. When she opened her mouth and bore down on his nose, he shrugged her off and moved away. She’d follow and repeatedly throw herself on him as they continued the game they both enjoyed.

Eyes bleak, mouth set in a straight line, shoulders slumped, Candace radiated distress.

Maybe Hollis would finally root out the cause of her friend’s unhappiness.

“Always glad to see you and Elizabeth. Aren’t we lucky with this weather?” she chirped.

“We are,” Candace said without conviction. “I’ll get a chair.” After she’d hauled one from the garage, she folded herself into it and said, “I’m being selfish. I should have stayed inside. I’ll drive you crazy. I’m so jittery, I can’t concentrate on anything.”

Hollis examined Candace. Early in their friendship, Candace had identified herself as a fellow Virgo and a woman who prided herself on being an organized positive pragmatist. Dressed in tailored clothes, accessorized with conservative but high-quality accessories and shod in highly polished, “sensible” pumps she was a quintessential polished professional executive assistant. Today, baggy jeans, a stained and faded T-shirt, and a misshapen navy cardigan not only drew attention to her short, stocky body but emphasized her state of mind. Her square-cut chin-length brown bob, wide-set brown eyes and regular features devoid of makeup normally underscored her no-nonsense approach to life. Today the tension in her face telegraphed that she was anything but “in charge”.

Candace reached into her sweater pocket and yanked out a cell phone. She pressed buttons, listened, snapped it shut and stuffed it back in her pocket.

“My god, where is he?”

Her anxiety hung in the air.

“Who?”

“My brother.”

Hollis had met Candace’s brother, Danson, several times and knew that the muscular and athletic young man supported himself as a nightclub bouncer but spent time promoting and playing box lacrosse, the indoor winter version of the summer game.

“What’s the problem?”

“I’ve been calling him for days. Days and days. I’ve phoned his friends and his boss. He worked last Saturday. That’s the last anyone has seen or heard of him. His tenant, the guy who rents the second bedroom in his apartment, isn’t there either.”

“Is that unusual?”

Candace shrugged. “Search me. I haven’t met him. His first name is Gregory, and I haven’t a clue what his last name is.” She shrugged. “Apparently Gregory’s a sales rep who hates motels and wants his own place when he comes to Toronto.”

“So no one is there to answer the phone.”

“Not the apartment phone and not Danson’s cell phone. Last time I talked to him, he scared me, because he implied he was on the trail of something important. I’m frightened that something terrible has happened to him.”

“What and why?”

Candace shook her head. “It’s a long story, and it’s taken me a few days to get really worried. At first I was furious, especially when Jack showed up on Wednesday.”

“Jack?”

“Remember two weeks ago, when you and Danson came for Saturday lunch?”

When she’d met Danson in July or August, he’d struck Hollis as intense and obsessive. Her first impression had been confirmed at that mid-October lunch. It had been warm, and they’d eaten out here in the garden. She recalled lobbing an innocuous question. “Candace says you play lacrosse and…”

Danson hadn’t waited for her to finish. “Play, recruit, organize—lacrosse is officially our national sport. I bet you didn’t know that. Hardly anyone does.” He didn’t require a response.

“It’s a totally demanding game. You have to be totally fit, totally committed. I wish the government would pass legislation to make it compulsory in our schools. Forget football or even soccer. Lacrosse is the sport all young people should play.”

Candace intervened. “Hollis, it is a great spectator sport. You and I should go to a game after Christmas.”

Danson reached across the red and white checked tablecloth and laid his hand over his sister’s. “Candace, I have a favour to ask—a big one.”

Hollis sensed that whatever the request, the answer would be ‘yes’.”

“Remember when I went to Montreal a few weeks ago?”

Candace sipped her wine and nodded.

“I recruited a great player, totally great, and he needs somewhere to stay until he gets a day job and place to live.”

Candace toyed with the stem of her wine glass and waited with a half-smile on her lips as if she anticipated what was coming.

“Since you don’t have a tenant in the basement studio apartment, it occurred to me that he might camp out there for a few weeks. It wouldn’t be for long, and he’d pay rent,” Danson said.

Candace had looked as if she wanted to refuse but found it hard to deny her baby brother anything.

“It was a lovely lunch,” Hollis said now. “Danson wanted a lacrosse player to crash in your basement apartment. I recall that you said yes, but your expression said no.”

“Absolutely right. It’s hard for me to say no to Danson. He has a generous heart, and he’s always taking care of others. Sometimes it’s us, sometimes it’s friends, this time it was a lacrosse player. It’s a wonderful quality, but last week a woman at work told me her daughter would like to rent the basement apartment for a year. I didn’t want to turn down a year’s guaranteed rent. When I called Danson with the news, he understood and promised to tell Jack.”

Candace ran the fingers of both hands through her hair, interlaced her fingers behind her neck and pressed her head back as if trying to squeeze her tension away. She released her hands and crossed her arms over her chest. “Jack Michaels phoned Tuesday evening. He sounded so pleased that he had a place to stay that I couldn’t say no. He moved in on Wednesday.”

Elizabeth howled. MacTee had accidentally upended her, and she’d banged her head on the edge of the sandbox. Candace jerked to her feet and rushed to comfort the little girl. “You’re fine, Elizabeth,” she said as she picked her up.

Almost simultaneously, the basement door opened, and a young man who had to be Jack Michaels emerged. His face resembled an inverted white-enamel pie plate on which a kindergarten child had drawn round eyes, curved eyebrows, and a bow of a mouth. After that, the child would have smacked on a playdough blob for his nose and declared the face finished.

He took in the scene but said nothing.

Since Candace literally had her hands full, Hollis spoke up. “Hi. You must be Jack,” she said. “I’m Hollis, the upstairs tenant. What can we do for you?”

Jack stared at Elizabeth, who continued to scream. “I have to do laundry. Can I use the machine in the basement?”

Candace, who’d quieted Elizabeth, nodded. “You may.”

“I’d like to make sure I do it right.”

Candace put Elizabeth down and held up her hand to indicate she’d address Jack’s concerns in a minute. She spoke to Elizabeth. “Why don’t we give MacTee a break? I’ll uncover the sand box? Would you like that?”

Elizabeth stopped sniffling as abruptly as if she’d thrown a “do not cry” switch. “Water?” she said hopefully.

“Good thing I didn’t get around to turning it off for the winter,” Candace said to Hollis and Jack with a poor attempt at a smile. “I’ll fill your watering can,” she told Elizabeth. She unrolled the hose, partially filled a child-size, green plastic watering can and handed it to the toddler.

Elizabeth parked it on the sandbox’s seat, clambered in and plunked down amid a bright plastic toy collection. She grabbed a yellow shovel and scooped sand into a plastic pail. After adding two more shovels of sand, she poured water into the pail, stirred, looked thoughtfully at Candace and dumped the contents on her head.

Candace, squatting beside the sandbox, wasn’t quick enough to stop her.

Water and sand splashed over Elizabeth’s baseball cap and dribbled down her face and neck. She scrubbed at the mess, balled her hands into fists, jammed them in her eyes and wept.

“Anything to get attention,” Candace said and folded her arms around Elizabeth. “Time for a quick spray in the bathtub.”

Her gaze swung between Jack and Hollis. “Hollis, would you show Jack how the machine works?”

Hollis would have preferred hearing why Danson’s failure to phone had terrified Candace, but this wasn’t the time to pursue the topic. “Sure,” she said, called to MacTee and followed Jack to the basement laundry room.

Before Hollis left, Candace lowered her voice and said, “When Elizabeth’s cleaned up and had her morning nap, would you join us for lunch? There’s more to Danson’s story.”

Hollis agreed almost before the invitation left Candace’s lips.

Jack had parked a large blue duffle bag on the basement floor in front of the washer.

“It’s a basic machine,” Hollis said. She showed him which dials to turn. “Do you start practices right away?” she asked.

“No. They told us to come early to find a job and a place to live. We’re semipro, and we don’t make enough to live on. Too bad, or we’d be better players. That’s the way it is. I have interviews this afternoon,” he said.

“What do you do?”

Jack stopped sorting his laundry. “Anything. I don’t have specialized training, but I’ve worked in fast food restaurants, and I can probably get something that will mesh with the training schedule.”

“Good luck. I’m an artist, and my studio is here. If you need to know anything about the house or the neighbourhood, feel free to come up and ask me.”

“You’re here every day. I forget that people work at home,” Jack said.

“I do. Candace’s mother is here off and on during the daytime too.” She pointed to the ceiling, “She’s above you on the first floor. You may wake up at three in the morning and hear her. She’s a dancer and practices at all hours.”

“It’s already happened. I figured college kids lived upstairs, although the music was kind of strange. I figured they were Latin Americans.” Jack’s eyes widened, and his mouth made a perfect “o” before he said, “Candace’s mother is a dancer?”

Leaving him to digest his surprise, Hollis and MacTee headed back outside. Hollis didn’t know what had been causing Candace such distress, but it hadn’t just been her obsession with her brother’s whereabouts. Danson seemed like a normal, caring if somewhat fanatical guy. Hollis wondered why his sister was so concerned. What revelations was she about to hear?