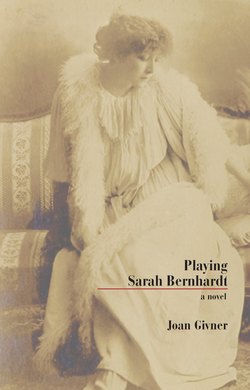

Читать книгу Playing Sarah Bernhardt - Joan Givner - Страница 6

I

ОглавлениеShe was playing Sarah Bernhardt when it happened. Perhaps that was part of it, for Sarah herself had been plagued by stage fright. “Le trac,” she called it, “fear.” There were two kinds, Sarah said, “the kind that sends you mad, and the kind that paralyzes.” The whole cast would wait in horror while Sarah stood transfixed, speechless. Of course, it might have been a trick to create suspense. That would have been in character, too, because she always staged a dramatic recovery.

Harriet hadn’t recovered. Not on the first night, not on the second, not on the third. Each time she was striding across the stage when she was suddenly struck dumb, every part of her body frozen — her limbs, her vocal chords, her mind. It happened always at the mid-point in the play. So there was no alternative but to quit.

The voices rose around her in a chorus, like the women of Thebes, scolding and predicting doom.

“You can’t run away from it.”

“Just lay off the sauce, Harriet, and you’ll be OK.”

“See somebody. Get professional help and give it another try.”

“You can’t just run away.”

Oh, yes, you can. She ran away, speeding down the long, straight highway and into the foothills of the Rockies. She drove recklessly, taking the hairpin bends too fast and choosing the most dangerous roads. She stopped for gas and bought stale sandwiches and weak coffee in paper cups and picked up a newspaper, though newspapers never interested her. The theatre was her timeless world and its gossip her daily news. But she stopped in front of the historic markers, reading them as if they were stage directions:

Slowly, over millions of years, crustal pressures pushed the seabed skyward. Water, wind, and ice attacked the emerging land mass, but the mountains rose faster than erosion could whittle them down. About 40 million years ago, with uplift slowing, the Rockies began to waste away.

It had happened before, of course, this failure of memory; it happened to all of them. Even when she was young and starting out. Once she was playing Ophelia and craziness seemed natural. She’d stumbled, distracted for a moment, and the others had filled in. Then she’d garbled her lines, saying “his trousers all unlaced” instead of “his doublet all unbraced,” and afterwards they’d rolled about laughing. They said the improvisation was better than the original, that she’d improved on Shakespeare. It was the high point of the entire run. They all had these anecdotes; they were part of the repertoire. The youngsters didn’t mind; they covered for each other. Hung over, strung out on drugs half the time. Lapses were a joke, not part of anything permanent. They wet their pants at tragic moments, got fits of giggles, broke the props, and took it all in their stride. “I lost it,” they said with a shrug. “I freaked.”

But lately it had happened more often and caused more problems. Once she was an absent-minded old woman in an Athol Fugard play, and she covered for herself. She put her hands to her head and said she was losing her mind, turning it into an extension of the role, and the young girl playing opposite her immediately caught on.

The Bernhardt play also had a cast of two. They liked that these days; it cut down on costs, not needing to hire more actors. But this time her partner wasn’t about to help her out of it. He resented her from the beginning, disliked his role as Sarah’s ridiculous secretary, saw himself as a romantic hero. “A deplorable little billy goat of a man,” Sarah called Pitou, and that applied to the actor, too. So she never managed to recover from the lapse. Even now she couldn’t think of it without wanting to vomit.

It was a longish speech, and she was addressing the ghost of her old admirer: “We are the last of our kind, Oscar Wilde,” she said.

At that point each time the wires in Harriet’s head crossed, and Lady Bracknell’s words floated into her head: “To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”

And after that, nothing. Just an immense silence in her head. Paralysis. And the stupid jerk refused to come to her rescue.

“The last Romantics,” the prompter said, and paused. “The last bright banners of ego and happy selfishness.”

But it was no good. She couldn’t pick up the threads and go on.

Sometimes the real Bernhardt would come onto the stage trembling so badly she could only indicate her gestures. What was behind the histrionics? Were they diversionary tactics dreamed up so that one eccentricity might conceal another?

At dusk Harriet found a bed for the night in a hunting lodge full of the smell of wood smoke. There were Spartan rooms with narrow cots for mountain climbers, for people pitting themselves against nature, testing themselves to the limit, not for tourists who needed bedside tables and lamps so they could read themselves to sleep. She never lingered, taking off at daybreak before anyone else stirred. Sometimes she woke to a dense fog that obliterated everything. She was marooned like an icebreaker in Arctic waters, forced to sit by the window, drinking coffee and watching the mist lift and the mountain return like a dinosaur’s back, so close that she could extend her hand and touch it. Then it was time to leave, and she strode out so hurriedly with her actor’s gait that onlookers imagined an assignation, a rendezvous.

Bernhardt had tried to orchestrate her death just as she choreographed her life, arranging the mise en scène, choosing the hour of her last performance. She kept a coffin always in readiness, even (they said) taking it with her on tours. It was made of rosewood and lined with white satin. She posed in it for the photographers, lighting a tall white candle and holding a sheaf of lilies. “I often think about death,” she said, “but only to reassure myself that I shall not die until I am ready.”

Bernhardt was full of weaknesses, reckless passions, vanities, affectations, but she turned every liability into a triumph. She travelled with an entourage of sycophants and accumulated a menagerie. She bought cheetahs and monkeys and parrots and turned her household into a circus. What was that but a publicity stunt, something to scandalize the bourgeoisie? Her genius was that she made her antics add to her stature; they didn’t leach from it as certain drugs leach calcium from the bones. Her wretched husband and her misbegotten sister were morphine addicts, but Bernhardt herself was abstemious. She even sipped champagne abstemiously, liking the idea better than the taste. If she needed to ease her pain she used the theatre instead of drugs.

When the Duchess of Teck asked how she could bear the strain of acting, Bernhardt said, “Altesse Roy ale, je mourrais en scene; c’est mon champ de bataille” — “I will die on the stage; it is my battlefield.” No sordid deaths for her — accidents above the frostline on mountainsides, crumpled cars, rumpled beds, and bottles of pills in cheap hotels, notes scribbled to harrow the survivors.

Harriet would have no survivors; she had to face it: there was no one in whose affections she stood first. She had no children, only an ever-changing troupe of players straight out of drama school; no lover but a series of leading men. She had no home and no family, and she’d never saved a penny. She didn’t even have a voice of her own, only a ragbag of hand-me-down phrases from the parts she’d played.

She tried sometimes in the late afternoon to pass the time of day with waiters when restaurants were deserted. “Slow time of day,” she’d say, or “Has it been busy?” The question sounded ridiculous, like an operatic soprano attempting a popular song. She had no small talk, could only declaim theatrically in a carrying voice that filled the house.

“May I have ... a refill?”

“Were you an actress?” a waiter asked. The verb tense stabbed her.

Age hadn’t stopped Bernhardt. When she was sixty-three, older even than Harriet, she’d given a series of farewell performances, playing Hamlet and the son of Napoleon Bonaparte. Two years later she’d played Joan of Arc. All Paris turned out to laugh at her. But she carried it off triumphantly. The crucial moment came during the scene with the Grand Inquisitor:

“Quel est ton nom?”

“Jeanne.”

“Ton age?”

“Dix-neuf ans.”

There was a moment of silence and then the whole house burst into wild applause at the sheer audacity of it. They did the same thing every time she played the scene.

When she was in her seventies, Bernhardt played with one leg amputated, played on and on until she couldn’t move across the stage without assistance. But she always managed to seduce the audience, make them fall in love with her over and over again. When she played an aging woman painting her face “in order to repair the irreparable ravages of years,” she flung her arms out in a wide appeal and spoke the words softly. The audience gave her a standing ovation, and in response she even managed to stand up, balancing on one leg, hanging on to the throne with one arm, and with the other returning their love.

“The last bright banners of ego and happy selfishness.”

“To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”

Bernhardt hadn’t lost both parents. She hadn’t had two parents to lose. She hadn’t even had one. She’d been born to a sixteen-year-old Jewish courtesan, unmarried, of course, who farmed her out at birth. She’d spent the rest of her life making up for that deprivation. And who could blame her? Yet she’d idolized her son and been devoted to her granddaughters. That was love, wasn’t it? Round and round went these thoughts in Harriet’s head, and every one brought her back to that moment when her memory had failed and chaos had ensued.

Another morning, another chalet, another lake, another national park. When Harriet stopped at the toll booth to pay, she thought that the altitude and the mountain air were causing her to hallucinate, for her name leaped out at her in bold letters from the notice board beside the window.

“That name,” she told the park ranger. “That’s my name.”

“Do you want to use the phone to call home?” the woman asked pleasantly. “Just pull over.” So Harriet drove to the grass verge, left the car, and went inside the little hut.

At first she thought it must be radio work; why would anyone trust her to do more than read from a script? But, no, he assured her it was a “bony fidey” play. The place was a small prairie city, and it was a play by an unknown playwright. His tone was contemptuous. He had the script in front of him and said it wasn’t promising. It looked like one of those docudrama things they put on these days about famous couples, but given the circumstances.... He had the title, but he couldn’t remember the details.

She didn’t need the details; the title told her everything she needed to know. If it had been any other title, she’d have turned it down flat because, even if she didn’t mess up, it was humiliating. It was only one step above a play in a church basement put on by the preacher’s wife.

“Listen, Harriet, I’m doing you a goddamn favour. Take it or leave it. But I gotta know soon. So don’t fuck around. All right, then, by six o’clock tonight. I don’t hear and you’ve lost the part.”

The time ’twixt six and now / Must by us both be spent most preciously.

She drove down the main highway looking for a quiet place where the roar of traffic was muted by pine trees. At Red Rock Canyon, she parked the car and joined a line of people going around the ravine in single file, like ants round a crack in the pavement, falling behind as she pondered the signs:

The mudstone contains iron. Exposure to the air oxidized the iron, like rust on steel, forming the red mineral hermalite.

You could hang in bravely to the very end, like those doddering English actors on Masterpiece Theatre, too old to remember big parts but doing what were euphemistically called “guest appearances” and “cameo roles”! They were magnificent, their voices still resonant, and they won awards, too, for supporting roles — Lady Bracknell, Lord Marchmain, an elderly missionary in the last days of the Raj.

The creek is like a giant conveyor belt carrying the mountains piece by piece back to the sea.

Should she accept gratefully? Go through the motions with as much dignity as she could muster? Or should she decline proudly — refuse to be put on display as Cleopatra scorned captivity, preferring death? But she knew that death didn’t come easily except on the stage. No rockslide would obliterate her, no snake deliver a gentle sleep. It would be impossible to stage a glorious exit.

Six o’clock and here she was back again at the entry to the canyon, almost deserted now save for the animals with motheaten pelts, sickly from being fed junk food by the tourists. She had come full circle and was back at the first sign:

The crumbly bedrock erodes quite rapidly on its own. Unfortunately man hastens this process, as the red rock cannot endure your footsteps. PLEASE STAY ON THE TRAIL AND LET THE CANYON ERODE AT NATURE’S PACE.

Well, then, it was decided. Already her mind was beginning to script a new role. She would walk into the theatre and the buzz in the green room would stop, everyone watching her entry. And it would start up again, the good old backstage gossip, inaccurate, malicious, but infinitely diverting.

“Did you hear about Harriet? My dear, a mountain climber!”

“No! I heard it was a park ranger!”

Back at the toll booth, she placed her call.

“Yes,” she said, “yes, I’ll do it.”

He gave the dates of the audition and said he’d courier the script if she’d just give him an address to send it to. Where the hell was she, anyway?

“Send it to the Lakeshore Hotel.”

It was the play’s title that had clinched it. It was a name from her childhood, or rather from that imaginary world that had run parallel with it, peopled by extraordinary beings in faraway exotic places. She’d dwelled in that world the way her friends had dwelled in a world of royalty or Hollywood stars. And that world had been orchestrated by one magical being, the only famous person she’d ever come close to knowing and who she came to think of as a distant member of her family, a friend of her Aunt Nina’s.

And now, years and years later, when her aunt was gone, the name she hadn’t heard for years had been spoken again, conjuring that whole world back into existence. Mazo de la Roche. Surely this was a talisman against disaster if ever there was one.

“She never married,” her aunt had said as they looked at a photograph.

“Like you,” Harriet said.

“No, not like me, not like me at all,” her aunt said.

“Well, what’s she like, then?” Harriet said.

“Like nobody you’ll ever run across,” her aunt said.