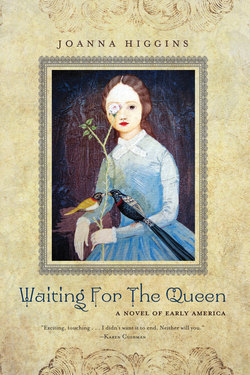

Читать книгу Waiting for the Queen - Joanna Higgins - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEugenie

A cold wind gusts through these American mountains, ruffling the churning river and further impeding the progress of our boats. On a map Papa showed us in Philadelphia, the river bears the Indian name Susquehanna as it meanders down through eastern Pennsylvania like gathered blue stitching on green fabric. The looping is most definitely accurate. But today the river is not blue; rather, nearly black. And the mountains are not green but in their sheer drapery of fog and mist, a dismal gray. Often a cask slides by, carried swiftly by the current. Or there might be great tree limbs with a few tufts of leaves that seem torn bits of flag. Our flag, I imagine in my fatigue. The flag of our beloved la France.

Cold penetrates wool and velvet and settles upon my shoulders like stones. Ah, the marquis’s perfidy! Talon promised fine dwellings, but where are they? We have been traveling now for a week upon this wilderness river. He promised a French town, but where is it? I lean to my trembling pet and wrap my cloak more securely about her. “Courage, Sylvette. Soon we shall learn if the marquis is a man of honor or not.”

Sylvette curls herself tightly against me, shivering in spasms. I try to comfort her, but a settlement appears along the bank that causes me to tremble as well—forest scraped clear for a few meters, and six rude log dwellings there, earthen colored. Smoke rises from chimneys, mingling with low cloud. Someone on a landing gestures toward our boats.

Mon Dieu! Can this be our promised town?

I close my eyes and hold onto Sylvette. When I open my eyes again, the settlement is behind us.

Merci, my Lady.

Fear eases its hold. I scratch behind Sylvette’s ears, feel the warmth of her. She hides under her paw and dozes. By now it must be midafternoon. Early this morning we embarked from the usual sort of camp we’ve been seeing along this river, merely a few board houses surrounded by a cluster of squat log huts more like caves. Last evening and again early this morning, several ill-clothed women and children emerged from these dark dwellings to stare at us. Maman ignores the uncouth gaping Americans. I do as well. But when a child ran up to Papa, wanting to touch his fur-trimmed cloak, Papa leaned down and lifted the boy high into the air and swung him down again. The child ran off, but not far. “Au revoir!” Papa called. The urchin smiled and threw himself at Papa again, and again Papa swung him upward. This time the child reached for the feathers on Papa’s high-crowned hat, but Papa set him down before he could tear them off. Then Papa took a coin from his waistcoat and gave it to him. Maman pretended to see nothing of this.

How these people bring to mind our peasants, the way they watch us. The boy’s mother finally pulled him away as if we were evil.

For such reasons and many others, the journey north from the port of Philadelphia has been distressing—the first hundred or so miles in a bumping coach to the river town of Harrisburg, and now these low boats and rainswollen river. And along the way, poor inns, poor food, and poor sleep, I tossing about on thin mattresses stuffed with crackling straw, tormented by dreams that always leave me exhausted. And then the dreams’ poisonous residue taints my days as well.

But the dipping boats lull, and it is difficult to keep my eyes open. I give in to temptation and am, at once, back at our château in the Rhône-et-Loire. The fields an orange sea, flames rising upon it like waves. I run down stone steps into a cellar. Maman! I call. Papa! But no sound issues from my throat. The cellar becomes a charred field, and I see a farm cart surrounded by peasants on the road bordering the field. In the cart, my beloved maid and companion, Annette. Then smoke rises from the cart. Spikes of flame. Peasants move back. The air around the cart brightens with fire.

I force my eyes open and the scene shrivels as if it, too, has burned.

“Ah, Sylvette.” Her white fur warms my cheek, catches my tears.

Why, Papa, I remember asking, did they do that to my Annette?

Because of her royal blood.

Do they hate us so, then?

I think—yes.

But what have we done to them, Papa?

Perhaps it may not be what we have done, so much, but what we have failed to do.

And that is, Papa?

Treat them as we treat each other.

But, Papa, they are not like us, so how can we treat them that way?

Papa had no answer for me. He said only that the times are most confusing, and one is certain of little now.

My heart is beating so as I hold Sylvette. “Maman,” I whisper, waking her. “How can there be fine dwellings in such a place? Perhaps they are taking us to some prison, just as they took the Queen to la Conciergerie!”

Maman shakes her head a little and stares at the river. Finally she whispers, “No, Eugenie. This is America. We have been promised refuge, remember?”

“But in such a wilderness? Why could we not have remained in Philadelphia? Philadelphia is America, too, is it not?”

“Eugenie, you well know why. Yellow fever has swept through there these past months, and now it is a city struggling against lawlessness and near anarchy. Did we flee the chaos and anarchy and terrible dangers in France only to endanger ourselves here? Of course not. Also, there are many Americans who favor the French rebels and would happily see us imprisoned or, worse, sent back to France—a death sentence for us! I wish to hear no more talk of returning to Philadelphia.”

“But the Vicomte de Noailles was there, Maman.”

“Oui, to arrange our passage and, earlier, to negotiate on our behalf. But you can be certain he will not remain. Even President George Washington has left for his home in Virginia. Far better for all of us to be some distance away, in a protected area, as Talon promises.”

“Promises,” I cannot refrain from saying.

“And as for the yellow fever, I am thus reminded.” She takes two cloves of roasted garlic from her reticule, one for each of us.

“But Maman, the taste lingers, and my breath becomes foul. Besides, has there not been a frost? It is said that when the frosts come, the danger of fever is no—”

“Frost or not, eat it, Eugenie. The garlic cannot hurt, and it may help, still. Or would you rather douse your redingote and gown with vinegar as the slaves have been doing this week past?”

“And so have the slaves’ master and his family. Well, what can it matter, those daughters being so long of face and foot. Gowns soused in vinegar will hardly make any difference for them.”

Maman watches as I put the clove on my tongue. “You must swallow it now, Eugenie.”

Reluctantly, I obey. “Those slaves, Maman. They endanger us as much as Philadelphia might. Are they not from the Caribbean, supposedly the source of the yellow fever? Why must they travel with us? It is beyond insulting. And remember how we heard they are from a rebellious area? What if their loyalty to Rouleau isn’t so assured? How safe shall we be then? By allowing Rouleau and his slaves, the marquis has doubly betrayed us.”

“Eugenie. We know not whether the marquis has betrayed us at all. And why should he not offer sanctuary to Rouleau? We cannot begrudge the man. He, too, has suffered. Besides, there are but four slaves and those, by all accounts, loyal. You have seen the scars on that one. It is said he tried to put out the fire in Rouleau’s maison, a fire set by other slaves.”

“Well, but Rouleau is not nobility, though he pretends to be. A pompous little tyrant, ingratiating to us, but quite mean to his supposedly loyal slaves. No wonder the others rebelled, and perhaps these shall too. Maman, the Rouleau family cannot stay with us. Either they must go elsewhere or we must.”

“Eugenie, we have no choice in this matter.”

“But the stink of them! Dousing themselves in vinegar!”

“Lower your voice, please.”

“Well, but we agree, do we not?”

“Your speech is too direct. It is not seemly.”

“Yet it is the truth.”

“The truth must be better clothed.”

“Well, how can one better say that they are a threat to our lives? How can we best clothe that truth, Maman?”

“We could tell the marquis that we prefer not to have Caribbean slaves and commoners at the settlement. Better that they find more suitable accommodation elsewhere.”

“But that hardly makes the point.”

“It will express our displeasure.”

“Surely we wish to express more than that.”

Maman is silent.

“Well, I shall not douse Sylvette with vinegar. Nor my gowns.”

“Of course not, my dear. Nor shall—”

Maman lurches against me as our longboat spins backward and into the prow of the boat behind us. Water sloshes in, wetting my suede shoes, redingote, and gown. Maman and I right ourselves, and there is the Rouleaux’s youngest slave in the boat alongside us. Her cotton gown is sopping to the waist, her eyes wide with fright. The pole is useless in her hands.

“Idiots!” Rouleau shouts. I think he means us until he adds, “Look what you have done to the noble ladies and gentlemen! You shall be punished! Now, away from their boat!”

The younger of the male slaves pushes hard against his pole, his scarred face trembling with exertion. But the current is holding us locked fast, and both boats are losing hard-won distance.

“My fault, monsieur,” Papa calls. “Do not punish them, I beg of you. I lost the bottom again. They are blameless.”

“Nevertheless, comte, they should have steered clear in time.”

I bow my head to hide tears. Papa, poling with slaves and savage-looking rivermen in deerskin jackets and fringed trousers stained black with tobacco juice. Papa making apology to Rouleau.

“Mademoiselle,” Florentine du Vallier calls out. “Perhaps the lances on your family crest are in fact poles, do you think?” Florentine is sixteen and believes he is a great wit. He is also thin and pimply and, when not attempting jests, surly.

Still, the nobles in our boat laugh. Maman and I ignore them. But then elderly Duc d’Aversille, usually a kind and most generous man, addresses Papa, saying, “La Roque, had you remained in France, you might be wearing the revolutionists’ red cap and tricolor cockade by now.”

How dare he. I turn to stare at him and hope that Papa will come up with some sharp rejoinder, but Papa merely laughs along with everyone and then says, “If you knew what pleasure I derive from getting this boat to move in one direction or another, Duc, you would be vying for this work, I assure you.”

“Not I, Philippe. I am far too old for such sport.”

Everyone laughs again, but the Comtesse de Sevigy first gives us a falsely sympathetic look. Hypocrite! Supposedly, she is Maman’s friend. Oh, I can just hear her. Madame Queen, we have the most delightful little story to tell you about our river journey here. It seems that Comte de La Roque has kept his true talent hidden until now . . .

It will ruin us.

But an even greater fear is that the events of these past months have overburdened Papa’s mind.

The boats separate. Papa and the rivermen plant their poles in the river, lean forward, and pull. Our boat inches forward again. Rain drips from the rivermen’s broad leather hats. It sluices down off the boat’s canopy. Clouds descend even farther, obscuring the tops of these mountains bristling with leafless trees. But then Maman points to a patch of color on a mountainside—sienna, maroon, dark green, and lemon hues faded in the mist.

“Chêne,” Maman says. Oak. “And see that lighter shade? Lovely!”

“Like your brocade gown. Did you bring that one with you, Maman? You could wear it here, for the Queen. You know the one—you like to wear it on the Feast of All Saints Day.” I stop, remembering how we observed that holy day quietly, in Philadelphia, with no pomp or feasting whatsoever. Maman had worn one of her other, simpler, gowns.

“Non,” she says. “I did not bring it.” After touching each eye with her handkerchief, she gazes ahead, into the mist.

Soon the fog thins again to reveal a long tawny creature crouched on a tree that has toppled into the water.

“Maman,” I whisper. “A mountain lion!”

“Where?”

“On that tree trunk. Drinking from the river.” But even as I say these words, the fog thickens again, hiding the creature.

“You imagined it, Eugenie.”

“Non! It was there, truly.” I lower my voice, not wanting Florentine to overhear. “Mountain lions will catch Sylvette and kill her.”

“Eugenie.”

“We must go elsewhere, Maman. We must.” “But we cannot.”

“It will be impossible here. There is nothing but forest—and wild creatures. Perhaps Indians, too.”

“Not Indians, Eugenie. They have moved farther west, we have been assured. As for our dwellings, we shall have proper maisons. The marquis has pledged this.”

“Maisons with stoves?”

“With hearths and stoves, surely.”

“And servants?”

“Of course.”

“And furnishings and beds and drapery?”

“It has all been promised.”

The rain slackens, but clouds still curtain the river and mountains. The Caribbean slaves, poling the Rouleaux’s boat, sing in their poor French. Our boat is silent, the rivermen grim.

“Maman?”

“Eugenie, you tire me. Allow me to rest, please.”

“Just this, Maman. The Queen will come, will she not?”

“She will.”

“She has escaped her captors and will come.”

“Yes.”

“We shall see her again.”

“Of course.”

“Even at this moment she may be on a ship nearing America.”

“Oui.”

“Maman, you must speak with Papa. He cannot—”

“Eugenie, enough for now.”

Then for a long while there is nothing but cloud and rain and the faint singing of the slaves. It tempts me to close my eyes and sleep, but no! I must not. My Lady, let this day pass soon. We are cold. We have not eaten since morning.

I hold Sylvette close and promise her a warm room and food. I do not tell her how the rain gives this day—or evening, if that is what it is—a gloomy aspect I do not at all like.

At last the Marquis de Talon stands in the boat ahead of us and gestures with his plumed hat. Our three boats begin turning toward a break in the forest on the left side of the river.

“Mes amis, we arrive!” the marquis calls. “Long live Marie Antoinette! Queen of France!”

Appearing along the riverbank are a number of silent figures. Maman takes my hand in hers. Sylvette looks alertly forward. Beyond the figures, a few hutlike structures appear indistinct in the mist like something in a dream.

Breath leaves me. Mama is holding herself stiffly, while Papa sags in undignified fashion against his pole. The nobles in our boat begin murmuring as our boat glides toward the landing. Then the boat is held fast and except for Florentine and us everyone else disembarks.

“I refuse to leave this boat,” I am finally able to say. “The marquis must take us elsewhere.”

“Eugenie,” Maman says. “You are creating a scene.”

“I care not! This is impossible!”

“Come now,” Papa says. “We are all tired and prone to worrisome thoughts.” He offers his hand.

“And famished, too,” I add. “But non! I shall not leave until we are taken to a proper settlement.”

“The mist and cloud obscure the maisons, Eugenie,” he says after helping Maman out. “Come now.”

“Papa, I am . . . afraid.”

“There is nothing to fear, chérie.”

“You do not know that for certain, Papa.”

“Eugenie, you have been courageous for many weeks. Do not allow your courage to fail you now, at this moment of arrival.” He offers his hand again, but I lower my head and tighten my hold on Sylvette. After a while, Papa, Maman, and Florentine leave the boat. Rivermen replace the gangplank and pull the boat, with Sylvette and me still in it, farther up onto the landing and walk off.

“Eugenie,” Papa says. “Please. Let us go and find warmth.”

I look at his sodden cloak and boots and almost relent, but say, “Papa, the marquis has tricked us. There is nothing here.”

“Florentine,” Papa says, “remain with mademoiselle, please. I shall find Talon.” Florentine bows, and then Maman and Papa walk away. My heart hurts as I watch them leave. Smirking Florentine asks if I am about to pole the boat back to Philadelphia. “It will be easier, mademoiselle. The current will be in your favor.”

I cannot allow him to see how fearful I am, or how angry and hurt. When Sylvette begins whimpering, wanting to leave the boat, I extend my arm to Florentine and unsteadily step out onto a large flat stone. It seems to sway underneath us, and for a long while I can only stand there, hoping not to pitch over.