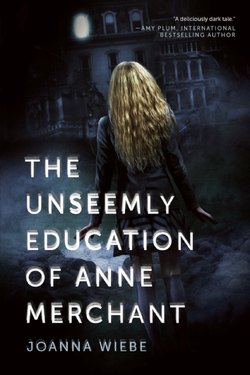

Читать книгу The Unseemly Education of Anne Merchant - Joanna Wiebe - Страница 9

ОглавлениеSINCE FIRST HEARING ABOUT THIS WHOLE GUARDIAN idea, I’ve been naively filling in the blank after the word Guardian with the word angel. Guardian Angel. Part of me had expected that my Guardian would be ushering me through life here, helping me make decisions.

But this scrawny man-child is no guardian angel.

A mouth-breather no older than yours truly, he looks like someone you’d expect to crawl out from under the floorboards in a Wes Craven flick. Pale irises, greasy hair, and bumpy gray skin with little orange hairs poking out all over his jawline. I look from him to Villicus and back. A prerequisite to work at Cania must be that you be the ugliest son of a bitch alive.

“I’m Ted Rier,” my Guardian says. He’s got a German accent, just like Villicus. “You may call me Teddy.”

“Ted is my newest assistant and the ideal Guardian for you,” Villicus adds, just as my pathetic excuse for a Guardian shuts the door and scurries to take the seat next to me.

Trying to catch my gaze, Teddy lifts my hand and kisses it. It is impossible not to notice the white flecks in the corners of his mouth. It is nearly impossible not to cringe—yet I manage—knowing my hand is so close to that or not to pull away too quickly when he smoothly says he’s charmed to make my acquaintance.

“It would be great,” I say as Villicus sits and Teddy opens his cheap-looking briefcase, “if someone could explain what exactly a Guardian is supposed to do. I assume there’s a connection between a Guardian and a PT, but I’m fuzzy on both.”

“If I may?” Teddy asks Villicus, who nods, allowing Teddy to field my questions. “Miss Merchant, first things first. I understand you attended a school prior to this one, and at that school you earned top grades.”

“Top of my class and top of the Dean’s List each year,” I admit.

Teddy smirks. “I didn’t know they had ‘deans’ at public schools.”

“Which is supposed to mean what?”

Neither Teddy nor Villicus seems to appreciate my tone much. As if they’re allowed to imply insults, but I’m not allowed a defense.

“You and I are on the same team,” Teddy tells me. “If I have offended you, forgive me. But the fact is that you are familiar with and comfortable in an academic environment that breeds much lower expectations than Headmaster Villicus demands here at Cania Christy. You were a top performer in California. You excelled among the uninspired. But now you’re among a new class of people. And you are competing for a title that, I give you my word, every student here wants more than you want to go to Brown on full scholarship.”

I’m about to ask how on earth he could know that when I realize that my dad must have put that info on my application form. So I skip to my second question: “I’m competing to be valedictorian, you mean?”

Teddy drops a leaflet in the hand he kissed, which still feels icky. I read its headline.

“The Race to Be Valedictorian: Only the Supreme Survive.” Dropping the sheet momentarily, I look from Teddy to Villicus, who is watching me with a small smile tipping the corners of his lips skyward. “Like ‘only the strong survive’?”

Teddy glowers at me, and I immediately realize that this may be the one school on earth where “stupid questions” actually do exist.

“What I mean is,” I backtrack, “if evolution—perhaps the most complex process in the universe, a process requiring unimaginable patience and rewarding natural talents—is all about the strong surviving, attaining the Big V must be an incredible challenge if only the supreme survive?”

Villicus stands and stoops behind his desk like a bird of prey, beady eyes glowing. He begins to speak—slowly, like one of those dictators you see in black-and-white films from the Second World War:

“I see that you have already adopted the vernacular of Cania students,” he says. “The Big V, as the valedictorian title has become fondly known here, is the highest mark of academic honor one can receive in school if not in all of life’s endeavors. Alas, who among this student body does not seek with full desperation the gift of the title valedictorian and all that it brings?”

I recall Pilot’s teary declaration but dare not mention it now, not with Villicus knee-deep in a speech he has surely given a thousand or more times. Truly, my key consideration in coming here was that the prestige of being the valedictorian of a school of this caliber would seal my future. I am as desperate as any for the Big V. Maybe more.

“The stakes are high—higher than anywhere. Valedictorians at schools like Taft, Exeter, and Eton go on to Oxford, the Sorbonne, Columbia.” Villicus’s eyebrow arches up his long, turtle-like head. “But an Ivy acceptance is just the beginning for the Cania valedictorian. No student here has a parent who doesn’t wholly wish him or her to graduate as the Big V. You recently saw Mr. Pilot Stone turn his back on the race, and I assure you: he is the only in the student body to do so. The Big V is, to be sure, a title that is beyond prestigious.”

With the grandeur of an old actor, Villicus sweeps back his shapeless garment and takes his seat again. Teddy licks the tip of his pen, and I notice he’s started filling in a form on a clipboard. My name is at the top of it.

“Miss Merchant,” Teddy says, “do you wish to be considered for the title of valedictorian at the end of your senior year?”

He and Villicus wait for my answer.

This is a no-brainer. Memories of my father rush at me, images of him whispering to me that I need to try as hard as I can to become valedictorian. Even Ben, who had so little to say to me, had that to share.

“Of course,” I say firmly.

Teddy ticks a box on the form. “Next,” he says, “I will inform you of the three rules for becoming valedictorian.”

“You would be wise to heed—verily, to meditate on—these rules,” Villicus adds.

I listen closely. As uncomfortable as I feel with these two kooks, as frustrating as it is to feel controlled by them, and as much as I wish I could bolt from this insanely hot room, this actually is important. The Big V is becoming more important to me as each moment passes, especially as I realize that this is an intense competition—and what Type A doesn’t perk up at the idea of competing?

The first rule is standard: I must have an outstanding GPA. Obv. Rule number two: I must follow Cania’s communication guidelines to a tee. These are both table stakes; you cannot be considered for valedictorian if you fail to meet these two baseline expectations.

“What are the communication guidelines?” I ask.

“To begin, there is absolutely no fraternizing with the villagers,” Teddy says. “No unsupervised phone calls. No Internet. No personal computers, mobile phones, tablets, or other such technical nonsense.”

“Sorry,” I interrupt to their vexation, “but how am I supposed to research my papers without Internet access?”

“All papers are handwritten, and research is conducted in our library.”

“Where there are computers?”

“Where there are books. Now, the third and final rule,” Teddy continues, bypassing my obvious concern, “is the critical one. The deal breaker. The game changer. The one thing that will set the superior apart. And it is this: you must sufficiently define and excellently live by your prosperitas thema.”

“What’s a prosperitas thema?” I’ve only just said the words when I realize I’ve heard of it already. “Oh, my PT.”

Teddy points at the sheet dangling between my fingertips as he explains, “Every student declares a PT, which is a statement of the inherent quality each mortal possesses that will make one a remarkable success in life.”

Skimming the handout, I read that my PT is supposed to complete the line:

When I grow up, I will be successful in life by using my

“So, it’s essentially a statement of how we’ll each be Most Likely to Succeed,” I summarize, and Teddy nods, though Villicus sighs as if I’ve just summarized the Mona Lisa with a single line about her smile.

“Once identified, your PT will be the ruler against which you are measured,” Teddy says.

Villicus piles on. “Candidates will be judged by their Guardians at every turn on whether or not they are satisfying their PTs.” His eyes land on mine. “You must live and breathe your PT, Miss Merchant, if you wish to become valedictorian.”

“If you don’t mind, what does that mean, practically speaking?” I ask. “How will I live and breathe it?”

“Suppose,” Teddy offers, “your PT is to…be selfish to succeed in life.”

“That sounds awful.”

“I would grade your actions over the course of the next two years against that PT. I would expect you to skip to the front of every line, fail to share, sabotage the efforts of your peers, especially those who are most desperate, and—”

“Steal money from a beggar’s bowl,” I suggest.

“Precisely!” Villicus and Teddy exclaim.

“I was joking,” I whisper. Neither hears me.

“Keep in mind,” Teddy adds, “that everyone around you is making every effort to live and breathe their own PTs. You won’t know it’s happening. You won’t know what they’re playing at. But that is precisely what they’re doing.”

Evidently, our PTs are assigned to us by our Guardians. Guardians are selected from the faculty, the housemothers, even the secretaries. One Guardian for each junior and senior—freshmen and sophomores don’t participate.

“I will be your shadow,” Teddy says finally. “Naturally we’ll be cohabitating at Miss Malone’s—”

“Wait, what?” I interrupt. “You’re living at Gigi’s, too? With me?”

“Where did you expect me to live?”

“There’s not even any room there!” I already know, though, that he must have claimed the guest bedroom, which is why I’m stuck in the attic.

“Miss Merchant,” Villicus interjects, his tone flat, “you have put up more barriers in these past ten minutes than the average student does in their entire time on this campus.”

“I’m just surprised—”

“And I’ve already considered,” Villicus thrusts on, “the possibility that you are not fit for this institution. Perhaps I ought to send you home. Do you realize that this morning alone I turned away a very wealthy man who implored me to let his daughter into the school? He’s flying out here tonight by helicopter just to see if he can persuade me. And here you sit! Snarling. Making demands.”

That shuts me up. Both Villicus and Teddy notice my reaction, and both smile; they share a joyless grimace. I’d love to be in a position to march out of here and stun them both, but with everything my dad gave up and all the strings he pulled to get me into Cania Christy, that would be a slap across his grizzled face. I wring my hands but know there’s no use in fighting this.

“So we’re living together, Teddy?” I choke out at last.

“The better to oversee your activities,” Villicus says.

Teddy piles on. “You’ll be graded at every turn. Morning, noon, night.”

As a junior, I’m supposed to work with my Guardian to document the activities I’ve completed that prove I’m living and breathing my PT. Guardians track progress daily, weekly, monthly. And, on graduation day, if I’ve pleased Teddy, he will argue my case before the Valedictorian Committee, which, with just one member, is the smallest committee in the world: Headmaster Villicus. The student whose case is best argued will be named valedictorian. Along the way, we’re supposed to keep our PTs private—no other students are allowed to know another’s PT as that may give them an unfair advantage.

It’s hitting me now, like lightning bolts shattering a gray sky, that Teddy is going to make or break me. He sneers at me like he knows I’ve just figured that out.

“Success does not happen by accident,” Villicus says. “Success is borne of looking inside oneself, recognizing one’s strengths, and making conscious decisions based on those strengths. That’s what your PT is. Because mankind is rarely capable of seeing its own strengths or flaws, your Guardian will assess you and identify your PT for you.”

I glance at Teddy. He just met me. How is he supposed to know my strengths and weaknesses?

Villicus goes on to explain that, although Cania has formalized and named the concept of the prosperitas thema, the greatest success stories of our time—even those who never set foot in this school—are each committed to a personal quality that has led to their success. Steve Jobs was innovation. Madonna is bold ambition. Warren Buffett is investment savvy. Oprah Winfrey is empowerment.

“Now, I see that you are already quite late for your scheduled meet-and-greet,” Villicus finishes. “This evening, then, at your shared residence, Ted will determine your PT. And you, Miss Merchant, would be wise not to resist him.”

By the time I race across campus through a rain shower that turns the quad into a slip-and-slide and, huffing, take a seat at the last open workstation in Room 1B of the stony Rex Paimonde building, I’ve already refused to let myself think that things can’t get much worse. I’m learning that they sure as hell can, so I don’t dare tempt fate. Instead, I rush to settle in, apologizing as I get my notepad out of my wet backpack, knowing I’ve interrupted their discussion. After all, I’m fifteen minutes late for a half-hour meet-and-greet.

But the teacher, Garnet Descarteres, this lovely blonde woman who’s maybe twenty, smiles and tells me to relax, get settled, I haven’t missed anything critical. She’s so pretty, I have a hard time believing she works alongside fuglies like the secretaries, Teddy, and Villicus. She explains that it’s her first year teaching here—she’s new, like moi—and that I should feel free to call her by her first name.

I’m about to smile when I glimpse someone I hadn’t expected to see: Harper. And, just like that, things go from bad to worse.

In total, there are twelve of us in the Junior Arts Stream, and, although we’ll have different classes, we’ll all meet daily for a morning workshop with Garnet. I’m relieved to find Pilot here and all the more relieved that Ben isn’t in this group—I’ve already guessed he’s a senior, so I shouldn’t have expected to see him. But a part of me, against my better judgment, did.

There’s also a very smiley girl, who must have declared a PT to be as sweet as cherry pie because she couldn’t appear more friendly and cherubic. The other nine students—including Harper and her Thai friend—engage actively with Garnet but practically snarl when someone else talks. Either everyone’s taking the Big V competition ultra-seriously or they all declared PTs to be gigantic snobs in life.

“We were just introducing ourselves,” Garnet tells me. “You’ll have plenty of time to get to know each other at the dance this weekend, but why wait until the weekend to make friends when you can start now?”

At the mention of making friends, smirks and sneers appear one by one, like fireflies in the night, on the brooding yet beautiful faces of most of the students.

Harper whispers to her Thai friend, “Even if I were open to knowing this bunch of losers, ain’t nothing gonna make me like Trailer Park Tramp.” She gestures my way. I’m meant to see it; I’m meant to hear her. “We don’t do charity in Texas.”

Ignoring Harper, I organize myself and ask, “Are we saying anything in particular in our intros, Garnet?”

“The usual. Where you’re from. What brought you here.”

“We don’t have to share our PTs, do we?” I ask, hoping to hear what the others will be “living and breathing” in the hopes of getting the Big V but knowing I’d have nothing to share yet.

No sooner have I uttered my question than everyone—even Pilot and the smiling girl—gapes at me like I just said Picasso is irrelevant.

“No, Anne,” Garnet explains slowly, tucking a lock of her gorgeous blonde hair behind her ear. “Students are meant to keep their PTs private. Only you and the school’s Guardians will know your PT.”

“Unless you don’t have one,” Pilot tacks on. His eyes meet mine and he flashes me a bright smile. “Some of us choose not to. It’s your right, you know.”

“Excuse moi, Garnet,” says a brown-haired boy with a tiny whiff of hair above his lip. He has a French accent so thick, it sounds like he’s eating peanut butter while fighting a head cold: every sound he makes is stressed, dragged out endlessly, or shoved to the back of his throat. He glances from Garnet to me. “Do you think we should continue to tell all our specific details?”

“If you don’t mind me adding, I was just thinking the same thing Augusto was,” the smiling girl adds, tossing me an apologetic grin before looking again at Garnet. “I would appreciate some clear guidance, if you wouldn’t mind, considering the, um, present company.”

“Well, Augusto and Lotus,” Garnet says, though she’s clearly talking to all of us, “why don’t you share as much with the group as you think you should, okay? Can we all self-edit? That’s an important skill for an artist.”

The introductions pick up where they left off before my interruption, with Augusto. He’s from Quebec. His parents own luxury ski resorts in Montreal, Banff, and Colorado.

“Before I came here, I was very much in love with a boy,” Augusto begins timidly, his cheeks flush. “The son of my own au pair. We could not share our love because my father is very traditional. So,” he flicks his sad gaze at me and fidgets with his pen, “I was at one of our family ski resorts with my love. And, holding hands, he and I boarded off the most incredible cliff together, soaring into the crisp and cool air. It was, without question, the most profoundly amazing moment of my life.” His eyes begin to water. “Unfortunately, my mère discovered us when we reached the bottom, and that was that. I was sent here after. I was a freshman at the time.”

Pilot has an intriguing twinkle in his eye that makes me think he probably wasn’t listening very intently to Augusto’s tale of forbidden love. “Can I go next?”

“If you’d like, Pilot. Now, tell us, is your father the California senator Dave Stone?” Garnet asks.

“Until the DNA results come back,” Pilot groans. “Yeah, he’s my dad. Real shining star, that guy. Anyway, let’s see, before I came here, I was at a prep school in sunny C-A, and I got caught up in some stuff my dad didn’t want me doing. It wouldn’t be good for his political career, see. So, long story short, I ended up here last November. Shipped away like so much riff-raff.”

Next is Lotus Featherly, the smiling girl and the personification of the word saccharine. As she talks about her life before Cania, I begin to look around the table. To really look. And I notice this: all of the students are flawless. I’m not exaggerating. These kids are perfecto-mundo.

Not gorgeous, per se. Not models.

Just unblemished. And pristine.

Lotus is so free of acne, she’d put those ProActiv spokespeople to shame; her skin shines. Augusto’s hair is almost too shiny. Pilot’s teeth are so perfectly straight and white. Harper’s figure is so Scarlett Johansson–voluptuous. They look like the untouched manifestation of perfect DNA. Flawless…and here I am. Swelling out of my little uniform. And with a crooked tooth and wild hair that’s starting to frizz up thanks to the rain.

“What brought you to Cania Christy?” Garnet asks Lotus, snapping me back into reality.

Like a waterline has erupted, tears spring to the girl’s eyes. Oh, no! There is no faster way to get on the Loser List than to cry publicly in school; that’s what bathroom stalls are for. “There was a situation,” Lotus whimpers, “and my dad was presented with an ultimatum concerning me. But he didn’t take it seriously. And so my parents ended up sending me here.” She drops her gaze and folds her hands. “It’s for the best, but I desperately miss home sometimes.”

Unspoken details hang in the air, details that would require a stealthy hand to grasp them without further upsetting poor Lotus. My hand has always been prone to shaking, so I don’t press. Not with Lotus sobbing like she is. No one else seems to care much, anyway. Maybe Lotus is known for emotional overreactions or maybe they’re as self-involved as all the richies I grew up with back in Atherton.

When it’s my turn to talk, I keep the details to a minimum and close off every emotion I have about the death of my mother. My story may have arrived on this island long before I did, but that doesn’t mean I have to confirm every suspicion these people have about me.

I begin, “I went to a regular school—”

“A public school,” Harper clarifies under her breath.

“Yes, a public school in California. It was good.” I pause as my brain skips past all the other stuff. “My dad thought it would be a good idea for me to come here because it’s sure to look great on my transcripts.”

Garnet half-smiles, but no one else reacts. The stories the rest of the kids tell are at least as vague as mine, but, unlike me, everyone seems to regard Cania as an undesirable last resort. Like Siberia for teens—somewhere they’ve been exiled to. Could it be that Cania isn’t the ultimate prep school, isn’t the sure way into the Ivy League? As if to solidify my suspicion, a guy with emo eyeliner tells his ill-fated story.

“My mom and the pool boy were vacationing in the French Riviera for the millionth time,” Emo Boy says with a forced lisp. He strokes his long bangs away from his face. “So, I mean, what would you do if your parents were always leaving you with the maids?”

“Easy. Go clubbing,” Pilot says.

“I know, right?” Emo Boy tugs his sweater cuffs over his thumbs and hunches into himself. “So I was at a rave, this madass club, and, yeah, I’d taken some E—hello, it’s a rave. And there was this bitchin’ dancer in a cage, just slathered in glow paint, right?” His voice becomes muffled as, endlessly fidgeting, he shifts his fists over his mouth. “So I climbed up on some speakers. And I leapt out onto her cage. And it, like, dropped from the ceiling. And my mom had to come home early because I was in the hospital. And she was so pissed. So, yeah, here I am.”

Harper’s Thai chum, Plum, goes next. She was a child actor-turned-singer in Thailand before Cania.

“I was doing lines of coke with my dad’s friend after some red carpet event,” Plum says casually, pulling a compact out of her bag and swiping red lipstick on. “That man was more a dad to me than my real dad. Anyway, I passed out in the VIP lounge. The effing paparazzi took photos and plastered them everywhere. Bitches. So, yeah, now I’m here. No life. No shopping. Nothing but the Big V race and a dance every now and then.”

Finally, it’s Harper’s turn. She openly shifts her bra to boost her cleavage and gazes at everyone but me, which is fine because it’s taking every morsel of my brainpower to sort out what she’s wearing. These uniforms are head-turning without modifications, yet she’s replaced her white shirt with a superlow V-neck tank, “forgotten” her tights, and hiked her skirt up wicked high. (I should not know she wears a red thong, and yet I do.) Sure, she has sleek hair, a cool Balenciaga blazer, and accessories that would make Rachel Zoe look like a pauper, but nothing can mask the truth: she’s over-the-top sleazy.

“This is my second year at Cania, y’all. My daddy said I should come here after last Christmas,” Harper says. Stroking a thick lock of red hair with both hands, she stares into space. “We had what you might call a falling out. I wanted Santa to get me a pink Hummer, but my stepmonster said if I wanted to get around so bad I should try riding our expensive horses for a change. So I thought of this great plan, y’see, to get back at her for it. And, sure, I admit I overdid it and my plan sort of backfired. But I blame her for that. Whatevs. No one was really happy with what I done. I had to come here, and that’s that.”

As I’m imagining Harper’s unspoken revenge attempt gone awry, her tone shifts. Her eyes narrow intentionally, like she saw someone do that on a bad TV drama once.

“But, well,” she continues softly, “y’know how they say you can cut off a dog’s tail, but you can’t sew it back on?” Confused silence. “I think you can. And with my plans to get the Big V, I’m gonna fix my mistakes.” She flicks a stern gaze at me. “Everybody best remember not to get in my way.”

That single comment starts an uproar with everyone but me and Pilot. He catches my eye and, smiling, mouths, “Get used to this.”

I stagger out of class and attend the rest of my orientation sessions, like Using the Dewey Decimal System (no Internet here) and Living Your PT. I survive lunch by avoiding the cafeteria; instead, I head down to the waterside, where I’m surprised to find dozens of kids sitting on logs and boulders up and down the water. Yet again, no one is talking to anyone else. No one.

The rest of the afternoon I notice that strangely cold behavior more. Everyone’s totally separated by this insanely tense isolation. I’d been worried about cliques I’d have to wrestle my way into via demeaning rites of passage—sleeping in a frozen bra or making out with, like, a rock—but that couldn’t be further from reality. Everyone here interacts formally. Coldly. Shaking hands when instructed but rarely meeting eyes. Twice, fights break out between kids who look so straight-laced and suburban—geeky, even—I have to hold my breath to keep from laughing. The only moments of relief come from Lotus, who happily pairs with me at one point, and Pilot, who seems to be smirking with me—like we’re in on some private joke—every time I pass him on campus.

“What’s so funny?” I finally ask him. It’s the end of orientation day, and we’re both leaving a workshop called Help Your Guardian Help You. Teddy was sitting next to me in the workshop; thankfully, Villicus called him to his office, and I haven’t seen him since.

“Funny?” he asks, but he’s smiling like even that’s funny.

“Am I missing something?”

“Aren’t you?”

“Do you only answer questions with questions?”

“Have you noticed that?”

Exchanging a smirk, we push through the doors. The air outside is like a wet slap.

“It’s like living in a raincloud here,” I say, buttoning my cardigan and longing for Gigi’s fish-stank coat. “Is it always like this?”

“You’ll get used to it.” Pilot halts in his tracks, forcing me to stop, too. “Listen, I’m not weird, if that’s what you think. I just wanted to talk to you more. Y’know, because it sort of feels like we know each other. Because of our dads and stuff.”

“Totally,” I say and watch my breath turn white before being absorbed into the misty air. “Your dad, like, got me in here.”

“From what I understand, your dad did that all by himself.”

“From what I understand, your dad is my benefactor.”

“Ha!” he scoffs. Pilot and I start to stroll again. We meander across the quad, heading toward the dorms and passing grumpy kids accompanied, at times, by stone-faced Guardians. “That’s the first and last time my dad will ever be called bene anything. I should’ve recorded it for posterity.”

“Well, it was awesome of him. I can’t say that I’d pay some random kid’s tuition to a place like this, even if I had the money and thought her art was half-decent.”

“Pay your tuition? Is that what you think my dad did for you?”

We stop again. Standing outside in this weather isn’t doing my hair any favors; I can feel it growing like a Chia pet on my head.

“Isn’t that what he did?” I ask.

“He supported your application, Annie. That’s what makes him your benefactor. And, besides, people don’t just pay tuition here.”

“Well, Cania surely can’t be the world’s first free private school.”

“That’s not what I mean. Tuition here is beyond cold, hard cash.” Nonchalantly, as if it’d be odd to be perplexed by such details, he lays it on me. “Your dad had to come up with your tuition. My dad wouldn’t be allowed to pay your way if he wanted to.”

But my dad doesn’t have any money. Even a couple grand is a huge stretch for him. Of course, I don’t tell Pilot that.

“Look, my dad told your dad about this place, which is a serious no-no. Secrecy is key—that’s the only way to keep this place from turning into a slum.” Grinning to take the edge off, Pilot explains that Villicus invites every student to Cania, which is why Villicus was stunned when my dad called him out of the blue and demanded he let me in. “When my dad told your dad about Cania, he broke the school’s code of secrecy.”

“There’s a code of secrecy?”

“When you’re dealing with rich screwballs, there are always codes for everything. You’ve gotta know the secret handshake, wear the club jacket, or flash the ring to get in anywhere worth getting into. Things have to be impossible to attain and insanely private for guys like my dad even to consider them. Even the people in that fishing village aren’t allowed to cross the line to come on the school grounds. It’s that exclusive here.”

I recall the red line I hopped over this morning. “Yeah, my Guardian mentioned something about not ‘fraternizing with the villagers.’ That seems extreme and sort of mean.”

“I think a marketer would call it exclusive.”

“I think a villager would call it mean.”

“You’ll never know. Because you’re not allowed to fraternize with them, remember?” His white teeth flash. “Anyway, there’s only one person our age in that whole village, so it’s not exactly like you’re missing out on a bunch of hot dudes drinking the town dry every weekend.”

Just ahead, some guy with his face painted white and his lips painted black—totally Goth—leans against the guys’ dorm building and waves at us.

“Speaking of hot dudes, there’s my roommate, Jack,” Pilot says, taking my hand and yanking me toward him. “He’s a senior, so don’t worry, he’ll be nice. You’re not a Big V competitor for him.”

Beaming through black lips, Jack turns to us as we approach. His dark gaze skips over my body and lands oh-so-obviously on my enormous ’fro. “Wow, either your PT is to raise rats in your hair or you lost a bet.”

“Annie, meet Jack,” Pilot says.

“It’s just Anne, actually.” I give Jack a slight wave. “Nice makeup. Does Halloween come early in Maine?”

Jack smirks and wraps an arm around my shoulder. “Okay, Afro Girl, you can stay.”

“Lucky me,” I mutter with a small smile as he releases me.

“I was trying to explain tuition to Annie.”

“Ah, yes,” Jack says, pulling out a cigarette and peering at me as he lights it. “Tuition. Not your usual twenty grand a semester.”

I almost choke on my own saliva. The idea that my dad could pay anything close to that sort of fee is—it nauseates me.

“How much is it?” I ask, hiding a grimace.

A thin curl of smoke escapes Jack’s lips as he chooses his next words with what seems to be great care. “Let’s just say that if you want your kid to get in here, you pay. Big time.”

Shooting a sharp look Jack’s way, Pilot adds, “Traditional tuition wouldn’t set Cania apart enough. Ivy League schools want the best, and Cania Christy does what it takes to prove it’s producing the best—from the ridiculously motivated valedictorians it churns out to its code of secrecy to the slightly inflated tuition it charges.”

“So how much is it?” I repeat. Just as I do, Harper and her posse stroll by, flicking their hair over their shoulders in perfectly timed unison. Is it wrong to want them to topple over in their six-inch Louboutins?

With equally tight grins, Pilot and Jack both shrug.

“If you have to ask, Annie, you can’t afford it,” Pilot says, chuckling.

By the time I head to Gigi’s, crossing that red line again and trying hard not to look at the house the beautiful Ben Zin calls home, I’m exhausted. If the tiny, wobbly little cottage felt at all like home to me, I’d collapse on my bed and nap until dinner.

But it doesn’t.

And the fact that Teddy’s standing in the doorway, with his notepad in one hand and my abandoned coat in the other, watching my every move as I walk up the gravel path, doesn’t help.