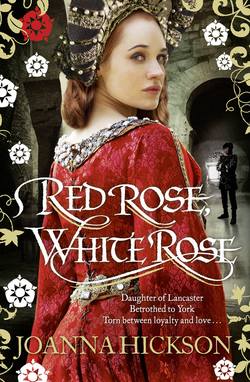

Читать книгу Red Rose, White Rose - Джоанна Хиксон, Joanna Hickson - Страница 15

6

ОглавлениеAycliffe Tower

Cicely

The squat tower seemed to rise out of a deep tangle of briars, which at this early spring season were just beginning to hide their fierce thorns behind emerging green shoots. Someone had struck on the ingenious idea of planting wild roses in the sparse patches of soil that littered the rocky foundations and these now formed a dense, flesh-ripping defence against any enemy attempt to scale the walls. Only the entrance to the undercroft, guarded by its latticed yett and a pair of thick iron-bound oak gates, remained free of this thorny barricade so that both people and animals could speedily take refuge in an attack. Gazing at these impenetrable thickets of briars my first random thought was to wonder whether they bloomed red or white. The red rose was one of the symbols of the Royal House of Lancaster, loyally supported by all branches of the Neville family, ever since my father had changed his allegiance from King Richard to King Henry. Planted here in Lancastrian-held soil by a Lancastrian vassal, it occurred to me that it would be ironic if, when they flowered in June, these defensive English roses were not red but white.

After struggling with a gargantuan lock and key, Tam and Thomas managed to get the yett and the gates open, but in order to reach the narrow tower stair we were obliged to cross the lower chamber, where until very recently a herd of cows had wintered. As a result the earth floor was still mired with their excrement so that our boots and the hem of my skirt quickly became filthy. I shut my mind to the stench and the image of rats scuttling over my feet and headed for the stair.

The upper floor was divided into two chambers, the first furnished with a few rickety benches and a heap of grubby sleeping mats piled in one corner. There was a cold, ash-filled fireplace in one wall. The deep gloom was preserved by tightly closed shutters; these Tam hastened to throw open, allowing welcome light and air through the two small window holes, but the smell of cattle dung still clung with fierce pungence and I clamped my hand over my mouth to stop myself gagging. Bidding me to duck my head, Sir John ushered me through a low door in the rough stone dividing-wall which led into another room containing a settle placed opposite another dead hearth and a low bedstead which lacked any mattress.

Eying this, I asked coldly, ‘Is it part of your plan, that I should sling myself on the bed-ropes to sleep, Sir John?’

‘We have brought mattress bags,’ he replied with a hint of a smile. ‘I will have Thomas send villeins out to fill them with myrtle leaves. They make fragrant bedding.’

‘I must take your word for that. Until I came to Brancepeth I had never slept on anything but feathers.’

‘Perhaps then you will begin to understand the difference between a castle and a hovel.’

‘I might, but I do not see how that will make me favour your cause.’ I shot him a sceptical glance.

Ignoring this challenge, Sir John removed a large iron key from the lock in the heavy door to the chamber and held it aloft while he spoke crisply and concisely. ‘You will sleep in here, the maid where you will. Tam and Thomas and I will sleep in the room above. There will be no keys but there will be a constant guard on the yett and a watch on the tower roof. Otherwise you are free to roam. The guard will not stop you but I do not advise trying to venture beyond the perimeter of the policies, due to the surrounding bog. Whole oxen have been swallowed by it in the past, when they strayed too close to the edge. The path is marked as you saw but the posts are removed at night. Only the reeve knows the safe route. Now I have arrangements to make. A meal will be served very soon. I hope you will join us.’

With a small bow he left the room, closing the door behind him. True to his word there was no dreaded sound of the key in the lock. I stared after him, trying to fathom his intentions in bringing me to this cheerless, dank little tower. To change my view of the Neville family feud?

The promised ‘meal’ was day-old bread, hard cheese and raw onion served on a trestle table. The men had removed their gambesons and boots and sat comfortably in tunic and hose, pointedly discussing Thomas’ inheritance.

Tam Clifford was succinct in his assessment of Aycliffe. ‘This place is a dump,’ he said. ‘What are you going to do about it, Thomas?’

Thomas pursed his lips. ‘I really do not know. I will have to win some big prizes at tournaments when I am knighted, if I am to build new domestic quarters.’

With a sly glance at me, Sir John remarked, ‘In any case it is no place to rear a family. Bogs may be a good defence against reivers but children do not thrive in them.’

‘True,’ Thomas drawled, downcast. Then, with a cheeky look at his brother, ‘John, you do not seem to be in any hurry to marry. If you are not going to take possession of the constable’s quarters at Barnard, perhaps I should move in there.’

It was news to me that Sir John was Constable of Barnard Castle, a royal stronghold not far from Raby. I supposed the post was connected to the earldom and had gone to the Brancepeth branch of the family.

He scowled. ‘As you well know, commanding a garrison like the one at Barnard is no task for a squire. Besides, I have every intention of using those apartments myself in due course, other duties to our brother permitting.’

‘Well I hope you take the young heir with you when you do. It is time young Jack escaped maternal rule,’ remarked Tam Clifford. ‘He is being mollycoddled.’

This criticism from Tam did not surprise me, even though it was of his own mother. I had already gleaned the impression that all the men of Brancepeth found the countess difficult to live with. I had only been under her roof for one night and found even the prospect of rat-infested Aycliffe Tower preferable.

I was uncomfortably aware that I needed a clean kirtle and the hem of my gown still reeked of cattle dung, although Marion had brushed it, but I found myself enjoying the cut and thrust of male conversation again. Having shared my brothers’ tutors for years, recently my mother had removed me from formal education and obliged me to acquire more feminine skills from her ladies. However, I now took care not to make any comment or contribution. Once or twice I felt Sir John’s gaze lingering speculatively on my face and guessed he was assessing my frame of mind; whenever I caught his glance he turned away.

The meal was soon ended and I decided to test his assurance that I could roam the tower’s surroundings at will, even if it meant crossing the dung-covered floor of the undercroft once more. I was agreeably surprised to find the dung had been cleared and our horses installed there, with fresh straw spread around them. Some of the villagers had obviously been called from the fields to perform this task and I met one of them carrying a tinder-box into the tower, to set fires in the upper chambers, I hoped, for I assumed the evening would be cold, though the sun still shone brightly by day. The guard on the yett saluted as I passed but made no attempt to stop me.

The rocky island on which the tower was built was also home to the manor village and the workers’ cotts. Buildings clustered around an area of land where there was enough soil, remarkably, to accommodate gardens and the burial ground of a small stone-built church. The cotts were roughly fashioned:wooden cruck-frames, walls of lath and mud-plaster and roofs covered with some sort of reed weathered in most cases to a dull dun colour, but streaked green with moss and lichen, and each leeward gable had a black-ringed hole in it where smoke escaped from within. Each cott had a small vegetable garden, fenced with woven briar hurdles against the lord’s herds of pigs and goats which roamed the rocky demesne at will. A few chickens pecked listlessly in wattle coops, being reared no doubt as rent in kind to be paid at the next Halmote. I wondered if Sir John would preside at the Aycliffe manor court, at least until its putative lord reached his majority. It seemed unlikely that the earl, crippled as he was, would ever travel to this bog-bound manor.

Skirting the village and rounding the back of the tower, I discovered to my delight that Aycliffe possessed an unexpected pocket of natural beauty. On this south-facing side of the rocky outcrop the ground sloped gradually, a grassy meadow dipping gently to the shore of a small lake, the sort fell-dwellers called a tarn. Unlike the stagnant pools we had ridden past on our approach through the bog, this water gave evidence of being fresh and clean, spring fed and life-giving. Encouraged by the early-season sunshine, green shoots were sprouting from the tangle of brown reeds at its edge. Occasional flashes of silver beneath the breeze-rippled surface revealed the presence of small fishes offset by the background of the silt-covered bed of the lake in the transparent water. Water birds ducked in and out of little islands of vegetation, investigating potential nest sites.

In shadows cast by a stand of stunted willow a heron stood like a statue. I pondered the riches that this small lake brought to the manor folk; fish, roofing material, baskets, wildfowl, irrigation and, above all, fresh drinking water. As well as refreshing the spirit with its beauty, its products were the reason the manor was here at all.

I wandered down to stand on a lichen-covered rock that jutted out into the lake. The water tempted me to squat down and scoop up water to splash my face, and as I did so I became aware of footsteps behind me, then a flat stone skipped across the surface of the lake four times and sank, taking me and a busy pair of moorhens by surprise.

‘I had a feeling I would find you here.’

I sprang up, my face dripping, to find Sir John not ten feet from me, bending to pick up another stone.

‘The lake is Aycliffe’s jewel. It is the only thing that makes it habitable.’

‘It is beautiful,’ I said, dashing the water from my eyes. ‘And the peel could be also. Why does the earl not make it so? Drainage, a barmkin, some byres and stables, a church tower. These things are soon built.’

‘The necessary funds, my lady, have gone to swell your mother’s dower.’

I could not let that pass. ‘Every widow must have a dower. That is enshrined in law.’

‘Not three quarters of her husband’s estate.’ Sir John’s face was stern. ‘What widow needs so much?’

I fought down an urge to agree with him by reminding myself that it was my mother’s closeness to the throne and the king’s patronage which had brought such wealth to my father.

‘My mother’s dower is one third until her death. The rest is entailed for her sons. All widows have as much. That is why so many younger sons fight to win them in marriage, is it not? Even if they are ancient crones! You could do so yourself, Sir John. If funds are so urgently needed I wonder you do not.’

‘I have no inclination to the wedded state,’ he retorted. ‘The earldom has its heir and due to my brother’s infirmity I am its steward. No, it is Thomas whose future is threatened because his betrothal was made when your father was alive, before the terms of his will became known. His bride-to-be is Margaret Beaumont, a widow with a substantial dower. She was married as a child to Lord Deyning but he died before they were bedded and she was betrothed to Thomas soon afterwards. Her father says now that he will not allow that dower to be squandered on a penniless younger son, even one who is the brother of an earl, and he is taking legal steps to break the contract. His strongest argument is that Thomas cannot provide a home suitable for the daughter of a viscount and he is right. Thomas will lose a valuable marriage to a girl of whom he has unfortunately become fond, because your mother hoards all the best Westmorland lands, which she does not need as your father ensured that all her children made advantageous unions. That is why I brought you here, to see the effects of her avarice for yourself.’

This remark stirred my capricious temper and I felt the blood rush to my cheeks. But though greatly tempted to deny my mother’s employment of the third deadly sin, I reminded myself that only one thing mattered, to escape back to Raby. Angrily confronting my abductor would not help achieve this and so I bit back the furious protest that sprang to my lips and took a deep, steadying breath.

‘Thomas is young. There will be another marriage. But I still do not understand why you cannot solve your family’s difficulties by making your own advantageous match. Whether inclined to matrimony or not, it is surely your duty, unless you are drawn to the religious life.’

It was his turn to exercise control. I could see his chiselled jaw clenching and unclenching as he turned away and let his gaze wander across the lake to where a pair of water birds were performing an elaborate ritual, shaking their crested heads to alternate sides, rearing up in the water and making each other gentle gifts of dripping weed. It was a charming sight but I was not prepared to let him retreat into ornithology. Leaning round to catch his eye, I shot him an encouraging smile and waited patiently for his response. When it came it took me completely by surprise.

He gestured towards the birds, busily involved in their courtship and unaware of the human passions building beside the lake. ‘I have been told that grebes like these mate for life and rekindle their relationship every spring by performing this extraordinary dance. I have seen it many times and I believe it demonstrates God’s intention that all creatures should make faithful partnerships. Did He not tell Noah to take only pairs of animals into his Arc? The Church teaches us that birds do not have souls and cannot experience human emotions like love and happiness but such behaviour indicates to me that they can only build their nest and lay their eggs if they have established some sort of bond. This ritual allows them to trust each other.’ He turned to face me and his expression was one of extraordinary intensity, grey eyes boring into mine. ‘I feel like that about marriage. Of course as noble men and women we must go through all the formal procedures of betrothals and contracts but I will only make a match with someone I can love and with whom I find a mutual understanding. So far I have not found such a one and I do not feel obliged to set my feelings aside to enter into a loveless marriage just because protocol declares it to be the right thing to do.’ Once again he turned away. ‘There, does that satisfy you? Or perhaps you now think me weak and hopelessly romantic?’

I was seventeen. Like most teenage girls I had cherished the notion of courtly love portrayed in the songs and lays of the minstrels who entertained us at feasts and celebrations, but ever since childhood I had been schooled to accept that such romances were fairytales; fairytales which were not for Nevilles. We were overlords, the rulers of the north; we had to make alliances with other noble families to perpetuate the power we had accumulated. Marriage was one way of achieving this. It secured treaties and preserved loyalties and I had to fulfil the role which God had given me by doing my duty and marrying the man my father and the king had chosen for me. Adolescent yearning for romantic love must be denied. I was, therefore, dumbstruck to encounter a man of power and position who not only cherished the concept of love and happiness but felt able to deny his obligation to God, king and family in order to do so.

I stared at Sir John wide-eyed and he, in his turn, wrinkled his brow in challenge.

I managed to hold his gaze but my heart lurched in a bewildering way. ‘I understand the desire to break the rules,’ I said faintly.

‘But you will not?’ His frown of disappointment forced me into a desperate attempt to make light of it.

‘It would take a braver woman that I to defy the Church, the king and my mother!’ I protested and when he did not react I stumbled on. ‘Perhaps my parents had that kind of marriage. My mother certainly loved and trusted my father. Perhaps he repaid that trust in the way that he fashioned his will.’

It was not the response he wanted. With a sudden exclamation he stooped, picked up another stone and hurled it violently across the surface of the lake towards the grebes, causing them to break off their dance and dive underwater in panic.

His voice cracked with emotion. ‘No! The old earl was much too shrewd ever to let his heart rule his head. When I was young my father served with him on the Northern March and we lived in his household for several years but when my father decided to follow the fifth King Henry into France they argued violently. The old earl thought Neville duty lay in the north, defending the border, but my father was lured by the prospect of wealth and honours to be won across the Narrow Sea. The rift between them never healed and by that time the sons your father had sired with your mother were growing to manhood. When your oldest brother Richard came of age, the earl made it clear that he wanted him as his heir, but for all his wily diplomatic skills, he could not change the laws of England to achieve that.’

‘You did not like him then?’ For some reason the thought of this distressed me.

‘On the contrary, I loved him. He was always kind to us children, making us laugh and bringing us treats and presents. I was sad when he no longer came to see us but too young to understand why. Now I do, of course. My father had crossed him and the first Earl of Westmorland could never bear to be crossed, especially by his son and heir.’ The knight cleared his throat as if struggling to continue. ‘I was not with my father when he passed away in London but it was officially recorded that he died of the plague. I have never really believed that.’

There was something in the tone of his voice that drew from me an expression of horror. ‘You surely do not believe that my father had anything to do with his death?’

Sir John shrugged. ‘Not personally no, but these things can be arranged at a distance. And you have to admit that it served his purpose well, if he did not wish my father to inherit.’

‘No, no!’ I was incensed. My father had been a good man. I was certain of it. He was a powerful lord and a strong leader who demanded nothing less than complete loyalty from his vassals, but to arrange the death of his own son merely because he had defied him – I simply did not believe he could or would have done such a thing. Apart from any moral issue it would have condemned him to eternal hellfire.

‘You are mad, Sir John! I swear before God that my father would never have killed his own son or even conspired in his death. I demand that you withdraw the accusation in the presence of the Almighty. What good would it have done him anyway, while your father had a son to inherit the earldom?’

Sir John’s lip curled at that. ‘A son who was a cripple and a minor might possess no power against the might of an earl who stood high in the king’s favour. My brother Ralph told me that after my father’s death the old earl sent his lawyers to demand that he give up his right of succession. It was in the face of Ralph’s flat refusal that your father spent the next four years until he died making sure my brother would inherit only a fraction of the Neville wealth. I will swear that is true on any holy relic you choose!’

Before I could prevent him, Sir John reached out and grabbed my hand and his eyes were so full of earnest zeal that I found myself powerless to pull it free. The touch of his fingers sent a shocking thrill up my arm which seemed to travel to my heart, causing it to race uncontrollably. Yet I continued to protest. ‘No, no, no. My mother would never have allowed him to make such a demand of your brother. It is a wicked thing to do.’

Even as I spoke the words, I could hear the weakness in my own argument. I knew nothing of what plans and schemes my parents had made during my father’s dying days. I had never spoken with him about the other half of his family. All his children by his first wife were strangers to me, as were their children. Apart from the man who now held my hand and his brothers, I hardly knew which of them still lived.

Sir John pursed his lips wryly and nodded. ‘You are right, it is wicked. But you are not as familiar as I am with the wicked ways of the world. Even as we fight our family wars here in the north, in the south there are forces gathering around the young king of which he is also unaware. You and he are both too young yet to know how power corrupts people and causes them to act against God’s commands and the laws of the land. But you must trust me, Cicely, because I do know and I can help you to understand. Justice is a fragile flower but if we treat each other fairly and deal reasonably together then justice can still be done.’

I tried to pull my hand away because the contact between us was confusing me. The messages passing up my arm were in conflict with the thoughts tumbling in my head. The first made me eager to believe the words of the man before me, while the second told me he was spinning a tale. Then his other hand rose to touch my cheek and my mind seemed to swim into a warm blue cloud and become lost to my rational self. I closed my eyes and let my starved senses relish the caress, then I felt his mouth close gently on mine and for what seemed like minutes I reveled in the first rush of fevered blood my body had experienced. The warmth of the spring sunshine was as nothing compared with the heat generated by the pressure of his lips on mine and the surge of pleasure it released. My bones seemed to turn liquid and I felt as if only our joined hands and lips were holding me upright. No carefully taught rules or commandments remained to order my feelings or actions. I did not care if I was on the steps to heaven or the road to hell; whether it was the devil or my own intoxicating desires that were drawing me along this unmapped path.