Читать книгу A Store at War - Joanna Toye, Joanna Toye - Страница 6

Chapter 1 June, 1941

Оглавление‘Well? Will I do?’

Lily Collins hovered in the doorway of the small back parlour. Her brother Sid, shirt sleeves, flannels, wavy blond hair, broad shoulders – Sid was the looker of the family, and no mistake – his injured foot propped up on a stool, glanced up from his Picturegoer magazine.

‘Come in, then, Sis, give us a closer look!’

Coming in was just what she didn’t want to do. What she wanted, no, needed, to do was to get Sid’s swift approval, then shoot out of the house faster than a firecracker before her mum could see that Lily had dabbed on a bit of her powder and even (before quickly blotting most of it off) a smudge of precious lipstick. She’d only dared sneak down to seek Sid’s approval because she’d seen from upstairs that her mum was out in the back garden, sitting on a canvas stool in the sun, shelling peas.

‘Come on!’ urged Sid. ‘Let the dog see the rabbit!’

Lily edged forward. She was horribly aware of how young she still looked in her faded print frock and – horror of horrors – ankle socks.

Sid scrutinised her, his head on one side.

‘Um … your hair. What exactly were you aiming for?’

‘A mind of its own’ was the kindest description of Lily’s own fair hair. It made life interesting, she supposed, because she never knew when she woke up which way her strong-minded curls would have decided to arrange themselves overnight. She imagined them in the small hours, debating long and hard.

‘I’ll flop over her right eye if you stick out at an angle at the top.’

‘No, hang on, I stuck out at the top yesterday! Why don’t I do the flopping? And for a change, you can spring off her ear?’

It hadn’t used to matter that much. At school she’d had to force her hair back any old how with grips and a hairband, but for a job interview, and with hairgrips just one of the things that had started to disappear now the war was in its second year … The best she’d been able to do was a complex arrangement with as many grips as she could muster and a couple of combs – also her mum’s. The effect she’d been aiming for, since Sid was asking, was side-parted and crimped at the side – Bette Davis in Dark Victory, basically – but her brother’s face told her the effect was more like something from The Wizard of Oz. And not Judy Garland, either.

‘Sorry, Lil, I’m not sure …’

‘It hasn’t worked, has it?’

‘You’re ahead of your time, that’s all. Give it six months, a hairdo that looks like you’ve stuck your finger in the socket’s bound to take off.’

‘Sid! They’re never going to give me the job!’

‘No. They won’t. Not unless you get a shake on, have you seen the time?’

In her anguish, Lily hadn’t seen or heard her mother come in.

‘Now sit yourself down and let’s sort that hair out.’

Dora Collins crossed the room. Lily was her youngest child but neither being the baby of the family, nor, after two boys, being a girl – at last! – meant that she was in any way indulged. If their father had been around, it might have been different – a lot of things would have been different – but he’d died of a heart attack the year Lily was born and Dora had been left a widow with three children under five.

Lily’s stomach took a plunge.

‘Here we go,’ she thought. ‘She’ll see the make-up. I’ve had it.’

But if she noticed – and she would have done, Dora missed nothing – her mother said nothing. Instead she sat Lily down at the table, snapped her fingers for Sid’s comb, and began with practised eye and hand to tame her daughter’s hair. Miraculously she managed it with half the amount of hairgrips Lily had used.

‘Now you’re presentable,’ she said with brisk satisfaction. ‘If Marlow’s don’t take you on, well, it’s their loss.’

Marlow’s. Simply hearing the word set Lily’s stomach somersaulting again.

It had first come up at the end of the Easter term when her headmistress had called the girls in Lily’s year in one by one for the customary interview. She’d been sorry, she said, to hear that Lily wouldn’t be staying on to take her school certificate.

‘I’m sorry too, miss,’ said Lily with real regret. ‘But Mum can’t afford for me not to be working.’

Miss Norris sighed. As a bright girl unable to make the most of her chances because of her family situation, Lily wasn’t alone. It had been the case through all Miss Norris’s teaching career – all the previous decade and the one before – despite the Great War, despite the vote, despite the new opportunities that had supposedly opened up for women. And now another war, which had brought with it more opportunities – of a sort.

Miss Norris sighed again. It had come so close. In 1939 there’d been debate about raising the school leaving age to fifteen, but the outbreak of war had put paid to that, for the time being at least. And now that unmarried younger women had to register for war work – it’d be married women next, including those with children – there was even talk of women being conscripted before the end of the year – it also meant that girls like Lily were in demand for the jobs they’d left behind. Shops, cafés, laundries, pubs, hotels … there were plenty of jobs for fourteen-year-olds. In fact the country was relying on them to ‘do their bit’ as well.

‘What do you think you might do?’ Miss Norris enquired.

‘They’re looking for someone at the Fox and Goose – general assistant, they call it,’ Lily replied. ‘Or Mum’s got a friend that works at a laundry …’

Miss Norris looked pained.

‘Lily. You’re better than that,’ she protested. ‘You don’t want to go skivvying!’

‘Well …’

‘And I won’t let you. Let me make some enquiries.’

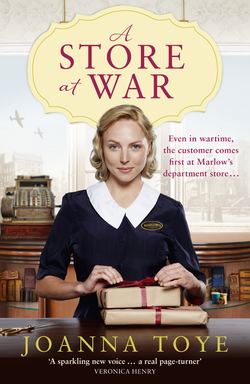

And so Miss Norris had made her enquiries, and within a few days told Lily of the opening at Marlow’s – the biggest department store in town. It was only a junior’s job – skivvying too, in its way, Miss Norris had explained apologetically – but it would at least have prospects – promotion, if she worked hard. And from the very start it would be better paid and what Miss Norris called a ‘better working environment’ than either of Lily’s other possibilities.

Lily had tried to look grateful – and she was. It was really kind of Miss Norris to have taken the trouble; she didn’t have to. But Marlow’s! Their motto was ‘Nothing but the best’. They might as well have added ‘for the best’ because who could afford to shop there? Not the likes of Lily’s family, for sure: she’d never been further than the black-and-white mosaic tiles in their doorway, and that was only because she’d sheltered there from the rain once, when she’d been in town buying a present – a scarf ring – for her mum’s birthday. Which she’d bought from the haberdasher’s in the market, of course.

And now Miss Norris expected her to work there? Marlow’s, with the drift of scented air which had escaped when the commissionaire had opened the door; Marlow’s with its oak-and-glass counters, polished parquet floor and dove-grey carpeted staircase – Lily had made sure to take a good look inside. Marlow’s … only the poshest shop in town. And Lily just a girl from a back street.

And now here she was, at two o’clock on a Monday in June, ready for her interview. Or was she?

Her mother jerked her thumb over her shoulder, jolting Lily back to reality.

‘Scullery, and double quick,’ she said. ‘Wash all that off your face. Wasting my powder like that! The nerve!’

Sid shot her a look that mixed sympathy with ‘might have known’ as Lily went to do as she was told. This never happened to Bette Davis, she thought wistfully, drying her face on the rough roller towel. Even at my age.

‘She doesn’t mean it, you know, our mum,’ said Sid consolingly as he walked, or more accurately, limped, alongside Lily into town.

Their older brother, Reg, had been eighteen the month war was declared, and had signed up straight away – Sid, too, enlisting for the Navy the minute he was old enough in April. Reg was doing well – going to be made up to lance corporal soon, he’d hinted – but poor Sid hadn’t got much further than training camp. He’d managed to crack a bone in his foot landing badly from the vaulting horse and, to his frustration, was now stuck at home till it mended. Not the sort of thing, he’d remarked ruefully, that you ever saw happening to James Cagney in the films – unless it led to him meeting a pretty nurse. Which in Sid’s case, it hadn’t, only an unsympathetic naval doctor with bad breath, apparently.

‘Thing is, she’s had to be mum and dad to us, hasn’t she?’ Sid continued now. ‘That’s why she lays it on a bit strong sometimes.’

‘I know,’ said Lily.

She knew her mum wasn’t really that cross, because after checking that Lily’s face was scrubbed as clean as the day she was born, she’d lent Lily her white fancy-knit cardigan, with her lucky horseshoe brooch pinned to it, and given her a hug and a kiss before she left.

‘So have you got all your answers ready?’ smiled Sid.

‘I don’t know what they’re going to ask!’

‘They probably only want to see that you haven’t got two heads. Let’s face it, they’re not exactly spoilt for choice at the moment, are they?’

‘Thanks very much!’ retorted Lily. ‘If you weren’t already on crutches I’d put you on them!’

But she knew he was only joking. Sid was four years older than Lily, but since they were children they’d always enjoyed teasing each other. Reg, Sid’s elder by eighteen months, was the quiet one, good with his hands, good at mending things. He’d spent the war so far being sent here and there for unspecified ‘training’ – Reg was very discreet – but after all that had ended up back at the searchlight battery in Nottingham where he’d started. This was a mixed blessing in the Collins household: it wasn’t what Reg had joined up for; on the other hand, Dora’s worries could be contained. Then, at last, his technical skills were appreciated – he’d been an apprentice mechanic when war broke out – so after more training, which this time he was happy to tell them about, he was going to be transferred to REME – the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers – to his great satisfaction, but their mum’s growing anxiety. Reg would be twenty in September, which meant he’d be considered for overseas service. The Mediterranean? The Middle East? The Western Desert? It was all much too worrying to think about.

‘Here we are, anyway.’

They stopped before the sandbagged façade of Marlow’s, its corner site bridging the town’s two main shopping streets. Even the Splinternet tape stuck criss-cross against the huge plate-glass windows – four down one street, four down the other, and two graceful curving panes each side of the entrance – couldn’t mask the elegance of the approach. Anyway, Lily thought, it gave the place a sort of charm, like the latticed windows of a cottage, albeit a cottage more the size of a mansion. The store’s name stood out above the entrance in stylish black on gold and was picked out again in gold on the mosaic tiles of the entrance. The huge clock which overhung the doorway showed five to three.

‘Right then. “The time has come, the Walrus said …”’ Sid squeezed her arm.

Lily gulped.

‘Don’t leave me, Sid.’

‘Of course I’m not going to leave you. I’m going to look at the ties,’ said Sid airily.

Lily’s eyes widened. At Marlow’s prices?

‘You’re never going to buy one here! Anyway, you’ve got a dozen ties already!’

‘Looking’s free, isn’t it? And they can’t stop me.’

The uniformed commissionaire gave them a hard look as he held the door open, but Sid’s salute and rueful glance at his foot brought a twitch of recognition from an old serviceman to a younger one and he swept them through with a gracious wave of his arm.

Once inside, Lily froze again. Now she was inside, properly inside, she could appreciate Marlow’s true magic. She’d never seen anything like it – or imagined such a place could exist in Hinton, their workaday Midlands town.

‘War? What war?’ she felt like saying, because there didn’t seem to be any shortages here. Overpowering scents wafted towards her from the cosmetics and perfume counters in front of her. To her right, scarves and gloves were fanned out in a rainbow of summer colours – palest pink through mauve to cornflower blue, and white through cream to lemon. Beyond were umbrellas both furled and twirled, handbags and shoes. Behind them, notices pointed to menswear, footwear, stationery, and gifts.

‘Come on, Sis, you don’t want to be late. Who is it you’re to ask for?’

The name was imprinted on Lily’s mind.

‘Miss Garner, staff office.’

Sid motioned her towards the enquiry desk.

‘Now you really are on your own.’ He squeezed her arm again. ‘You’ll be fine, kid. Just be yourself.’

With that he was gone, swinging himself athletically on his crutches, and attracting as he passed, Lily noticed, interested looks from Elizabeth Arden and Max Factor – or at least their immaculately-presented salesgirls.

The enquiry desk was on her immediate right. Behind it was a woman in her fifties who regarded Lily over spectacles whose design made them look as if they wanted to take flight.

‘My name’s Lily – Lily Collins. I have an appointment. With Miss Garner. Three o’clock,’ she said – or squeaked. Her voice seemed to have been replaced by Minnie Mouse’s.

‘Let’s see…’

The woman ruffled a couple of sheets on a clipboard and placed a satisfied tick against a typewritten line. She replaced the clipboard in a wooden slot to her right.

‘They didn’t tell you, then?’ she enquired.

‘Tell me what?’

The woman raised her eyebrows higher than her aerobatic glasses, but her smile was kind.

‘This’ll be the last time you use the customer entrance. The staff entrance is in Brewer Street, at the back. That’s if you get the job.’

If I don’t get the job, thought Lily, it’ll be the last time anyway. I’m hardly likely to set foot in here again!

On the third floor, Miss Garner, the staff supervisor, was holding forth on her favourite subject – the difficulty of getting what she called ‘the right type of girl’.

‘I never thought I’d see the day’ – she indicated Lily’s letter of application, written not so much with the help of as by Miss Norris – ‘when Marlow’s had to take girls from anywhere but the grammar school!’

Cedric Marlow shrugged. He was sixty-three, the son of the founder of the original Marlow’s (‘Capes, mantles and bonnets – all the latest designs from Paris!’) and had been in the business since he was twenty. He’d seen plenty of commercial ups and downs, plenty of staff come and go, and more to the point had seen one war that was supposed to end all wars be followed by this one. If he’d learnt nothing else – and he’d learnt a lot – it was that a business had to adapt to survive and accepting reality and adjusting requirements to suit what was available was the only sensible strategy.

‘We don’t have a great deal of choice, do we?’ he said mildly. ‘And I can’t see things improving when—’

‘When they bring in conscription for women. I know.’

Miss Garner looked briefly at the floor. She didn’t ever mention it, but she’d done her bit. She’d served in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry in the First War. She’d met her first love, too, when she’d nursed him back to health after the second battle of Ypres. Before he left for the front again, he’d asked her to marry him, and had become her fiancé, then her missing-in-action fiancé, then her missing-presumed-dead fiancé. His body, the body she’d bathed and tended back to health once already, was never found.

Miss Garner was too old now for nursing, or any interesting war work, and too useful anyway, doing what she did at Marlow’s, keeping the home fires burning, or rather somehow finding the staff to sell the coal scuttles and hearth rugs that flanked the home fires – while hearth rugs and coal scuttles were still available. Making do and mending, cutting her cloth … seeing the young, then middle-aged, staff leaving and replacing them with the halt, the lame, the very old – and the very young. Fourteen-year-olds, in fact.

A shaky tap on the door told them that the girl they were expecting had arrived.

‘Enter!’ called Cedric Marlow.

Lily’s interview was about to begin.