Читать книгу Zephany - Joanne Jowell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 5

ОглавлениеAs Miché’s nights have become sleepless, so too have mine. I lie awake thinking about this young woman – correction, girl – about to undertake the most important year of her schooling career, poised on the brink of adulthood, her most immediate concern the dress design for her Matric ball … becoming, in the space of minutes, effectively an orphan.

I turn now to a quiet bystander character, someone whom Miché has mentioned numerous times in our conversations as a source of unwavering support to her during this tumultuous time. Sophie Botha was Miché’s teacher and confidante at Zwaanswyk High School, a figure of quiet authority who remained close to Miché throughout her ordeal. She is not an ‘insider’, which is precisely why I’d like to talk to her – for her observer’s viewpoint – and she is the only one of such characters (friends, boyfriends, peers or superiors) Miché feels can offer objectivity. To Miché, most others are tainted with the whiff of the gossip-monger or publicity seeker – a class into which she dumps virtually all her friends from that time, whom she believes broke confidence by speaking to the media. Sophie Botha, on the other hand, offered an island of calm, faith and unconditional support when Miché’s own mother was ripped from her embrace.

I find Sophie Botha in a quiet restaurant outpost on the far end of Melkbosstrand. I quickly get the feeling that she is only prepared to speak to me because it was Miché’s idea. Her unofficial role as confidante for countless students means that her trust is hard earned, and she does not take that duty lightly. If nothing else, her personal honour code ensures that all information is privileged, and willingness to reveal it is reluctant.

SOPHIE BOTHA:

I’m not surprised you picked up reluctance on my part, because I’m not used to stuff like this – talking about other people’s lives. I help kids. I make myself forget what I’ve said and what they’ve said in our conversations because I want to keep their trust. So somehow I tend to move on and ‘forget’.

I think very few people know that I was involved with Miché. When she came to me, it was always at the school. She’d come through side doors and she needed it to be private because I think she’d had enough of the nonsense and publicity and people wanting all that sensation. I wanted her to feel safe and secure, to be able to share and just be herself, because at that stage Miché was so confused – she didn’t know what she was supposed to feel and whose side she was supposed to be on.

I was a teacher at Zwaanswyk for eighteen years. I taught Afrikaans but I was always the ‘mommy’ at the school: I was involved with the Christian Society so all the broken-winged little birds would come to me for hugs, when they had a need for love and support and talking. I did have a course in therapy as well just to back me up and help me. The children always knew: if you have a problem, you go to Juffrou Botha. It’s just the way I am. I think the children sensed that I truly cared.

I met Miché when she was in Grade 9. I had her for Afrikaans in Grade 9 and then also in Grade 10. So I got to know her before all of this came out. Miché was very into her religion – she’s strong in her beliefs, that’s the kind of house she grew up in – and that is what connected us at first. In class, I would not only teach about Afrikaans but also about life. One day, I gave one of my little life talks in class, and Miché came to thank me afterwards, saying that she wants to move closer to the Lord and she needed to hear those words. From then on it was like she felt free to come to me any time, just for a hug or to say hello or whatever. Even when she was no longer in my class, we were still close. We became friends on Facebook as well, where I could see her stuff and she could see mine. And then WhatsApp obviously made it even easier to chat.

Miché was a lovely child, the normal teenager. What’s normal? You have your ups and downs, days when you feel great, other days when you hate life. Miché was a normal teenager in that sense but very well behaved and respectful, with good manners – nothing wrong there.

Her nickname was ‘Poppie’. It suited her and I think she liked it – a poppie is a little doll, and Miché felt like one, she felt special. If she ever wrote me a letter or a message, she’d sign it off: ‘Ek is lief vir Juffrou. Liefde, Poppie.’

Miché had lots of friends and I think she was quite popular with the boys as well because she is a lovely looking child with a nice personality. Ja, just a lovely person. And she seemed to have a very good family. I didn’t meet them much – maybe at a parents evening or something – but you could tell that she was very well brought up.

Her boyfriend, Sofia’s dad, had been in my class too. He was also a lovely child but the two of them together – no. You get that in life – two people, or even a whole class, who are lovely as individuals but put them together and it doesn’t work. I think that was not a healthy relationship. It didn’t strike me in the beginning, but as their relationship progressed, I don’t think she was all that happy. I was very close to him at one point, when he was in my registration class, and he often used to come talk to me. But the two of them together – no.

I told Miché my reservations about them as a couple. I was always honest with her and I think that’s what she appreciated. I never tried to sugar-coat something. I’d tell her: ‘I want you to look at what I’m saying, consider for yourself and then make your own decision.’

Miché wasn’t in my class in her Matric year, so I wasn’t initially aware that she had been called to the principal’s office to hear the news. It must have been a day or two after that happened that the whole staff was called in. They told us that Miché was involved in an investigation for a child who went missing many years ago, and that they had the results of the DNA tests. We were told to be careful, not to speak to the papers, nor comment to anybody. We had to be aware to not put this child’s identity in jeopardy.

The entire staff room was in shock. It was one of those jaw-dropping moments where you just think, What?! You must be dreaming! All the teachers were stunned: how on earth is this possible? The child has been at Zwaanswyk for five years. Now her biological sister, who she’s never seen before, all of a sudden starts in Grade 8, but they don’t even live in the same area – what are the chances? I mean it’s so unbelievable that something like that could have happened. Crazy stuff.

My first thought was: if I’m feeling like this, just imagine what Miché must be feeling. So I contacted her after a couple of days and just said, ‘I love you, I’m here for you.’ I didn’t ask her anything, I just left it at that, and she contacted me when she needed to.

There was no one for me to discuss the case with. I prefer it that way. I don’t talk about someone else’s business because if that person wants to talk to me, they’ll come and talk to me. And that’s what Miché did.

MICHÉ:

I had left school that day with only my school bag, which I gave to my daddy at the Safe House. Marshionette got me toiletries and whatever else I needed to stay over, and we drove to Stellenbosch.

Marshionette lives in a very nice house, and they were all so welcoming and warm, her husband as well. We were settling in and I went to shower. Marshionette had my phone. When I came out, I told her, ‘I’d like to go sleep now, can I have my phone?’ But she didn’t want to give it to me. As nice as they all were there, I felt I just wanted to take my phone and call my boyfriend, or a friend, or anyone and say: ‘Come fetch me! Please! I don’t want to be in this drama.’ At that stage I felt, Gosh, I just want to go back to my life. This is nonsense. These people drag me into their situations and their troubled life. I don’t have time for this.

Marshionette said: ‘You can’t have your phone because an investigation is happening and there are possibilities … So that’s why we’re not giving it.’

Marshionette could always make me understand things. I remember she was sitting on her bed and I asked, ‘Then can you please at least just tell someone to bring me my clothes, my make-up, my hairdryer, my flat-iron – and my heels!’ And she did organise someone to go fetch those things.

At that time, I already had a sense like, Girl, you’re never going to be the same again. But how are you going to deal with this? That was my thing. How are you going to get through this? I looked at myself in the mirror and told myself that I resemble my father’s people, I don’t look like these others. There in her room, I asked Marshionette: ‘Do you think I really look like those people?’

‘You do look like those people. I’m just being honest. You wanted an answer – I do think you look like them.’

But for me, seeing is believing – and I didn’t, or wouldn’t, see it. I lay in bed and cried that night. I cried the whole night. I was like, I want my phone, I want to go home, I want my parents, my friends must be wondering where I am and what’s going on, the teachers must be so confused … I am so confused!

The next day was a Thursday. I got up and Marshionette made me breakfast. Then she showed me a headline in Die Burger that this baby might have been found. I promise you! The very next day! Up to this day we still don’t know who leaked the information; probably at the clinic or wherever they took the DNA test. The test results weren’t expected back until midday, and already the news was out. But I didn’t believe it. To me, that test had better be negative because I was going home to my family, home to my life.

We got dressed and went to the place where Leanna Goosen works – it’s a place for all the naughty boys, near Stellenbosch. On the way, Marshionette asked me: ‘What if this test is now positive? What would you do?’

‘I don’t know, I really don’t know. We have to see when we get there.’

We met Leanna there and we all sat in the office, waiting, waiting, 11 o’clock, 12 o’clock, waiting for this call to come through.

Leanna is the one who picked up the phone. And then, I don’t know why, but she started crying.

MARSHIONETTE:

From the minute we left the place of safety, even before that, Miché was just simply an adult.

I couldn’t understand how this child coped with what she was hearing, how she would take the facts, gather her thoughts, and just say, ‘Okay, let’s wait and see.’ We developed a very close relationship over the next while, and it always amazed me just how adult she was. The way Miché handled the whole situation was not like a seventeen-year-old child.

Almost immediately, we had a mother-daughter relationship, like in washing hair and blowdrying and everything. My sons were mad over this new big sister they had. From the minute Miché walked in, they just loved her. It felt like ages that Miché was with me. It was just about two weeks, but it seemed like ages. We had a ball together. And I finally had a daughter!

My main thing was to keep her away from the media and protect her identity because she was a minor. That’s where we got Ann Skelton in – she’s a lawyer for children’s rights, and Leanna arranged for her to be Miché’s lawyer, just to safeguard her so that her name is not all over the media. That’s also why we took her cell phone away – we didn’t want her on social media because we were scared that she’d be hurt by what people might say. But she challenged us for the cell phone, and in the end we gave it to her but we said she must block her Facebook account. Also, she had a boyfriend and she wanted to chat to him. So I gave her the phone just for an hour, to chat to the boyfriend and say that she’s okay.

The next day – Miché was with me the whole time, from after she was taken from school and first received the news – we were waiting for the DNA results. I can clearly remember we were sitting in Leanna’s office and eating. Sticky chicken wings and chips. Our nerves were down the drain and there Miché was, just sitting and smiling at us. I couldn’t stop eating because of the nerves. She seemed as calm as anything. And when she heard the results, she just said, ‘Well, now it’s out.’

MICHÉ:

When the call eventually came through, I sensed … Oh snap, it’s about to go down!

Colonel Barkhuizen was on the phone and Leanna was congratulating him, saying, ‘Well done, good job,’ and I was thinking, Dammit – this thing is probably positive.

Leanna was crying and she told me that she had really hoped it wasn’t going to be positive. Marshionette started crying too and she phoned her husband to say that I am that baby. I think the emotion was because they worked so long on this case, and now the product was sitting here right in front of them. They’d completed their mission.

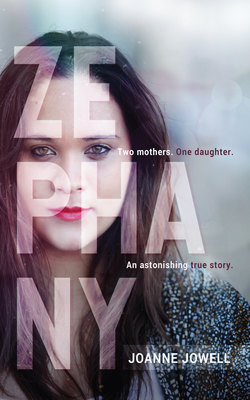

Leanna said, ‘You are the baby. You are the Zephany Nurse baby.’

And inside me, everything went dark.

I don’t know what happened to me that day. It was like the world went black.

‘But what’s going to happen now?’

‘Well, they’ve arrested your mother …’

That’s when it hit me. I didn’t cry, but inside … to hear that the person you love, the person you call ‘Mommy’ every day, the only mommy you’ve ever known, is being arrested … That’s not a nice feeling. Only criminals get arrested! How do you bring those two together – your mother and a criminal? How do you make sense of it?