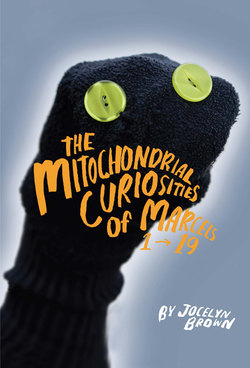

Читать книгу The Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 - Jocelyn Brown - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Two

ОглавлениеIn September I had an epiphany. Others called it a breakdown because I was fourteen and had recently cut my own hair. Everybody had an opinion. I got caught in a bad energy field (Rita); I was lazy (Joan); predictably nihilistic (Paige); anemic (Grandma Giles); possibly lesbian (Santini, school counsellor); underchallenged (Ms. Riddell, biology teacher); bloody brilliant (Leonard). I knew it was an epiphany because I knew what epiphanies were. The week before, I had happened to be in English 10 when Trenchey talked about epiphanies and he was quasi-interesting for the first and only time. That kind of coincidence has to mean something.

On epiphany day, things started as per usual. I was walking through Churchill Square, empty concrete heart of Edmonton. I had passed the sign that says ‘Wheeled sporting activities are not allowed.’ Wheeled sports are the only thing the square is good for, but that’s Edmonton for you, and I’m used to it.

Who knows why that day was so radically unspecial, but I was totally tabula rasa. Possibly Churchill Square oozed brain-damaging toxins and all my get-thee-to-school neurons had been eaten away so I could ephiphanize. Or, forget the carcinogens – maybe ugliness is enough for brain damage. Wouldn’t that explain practically everything?

I watched people walk by and so many of them looked like they wanted to sit down and stop everything. You could see them make the decision to keep moving. After a while I told myself, whatever, Dree, you’re just PMsing. I watched the guys looking for butts outside the doors of Edmonton Centre. Oh, go home, drink more coffee, I told myself. Then I saw the security guards watching the guys looking for butts. I went OMG, it’s Edmonton on Wednesday morning, get a grip. Then a man older than Grandma Giles yelled, ‘Learn to drive, you moron,’ from his truck, the woman he yelled at gave him the finger, he leaned on the horn and so did a bunch of other people.

We are so so done.

I thought of Joan in her cubicle and the hundreds – thousands? – of other people trapped in cubi-farms all around me. I felt the pull to jump back in, magnetic and strong. I didn’t move. I couldn’t not see what I saw. We’re talking full-on, factual data – like waiting for the bus when it’s thirty below and knowing it’s cold. I knew humans were finished.

It wasn’t about school being all traumatic. It’s just that when nothing matters, ninety-minute blocks of obsolete information are ridiculous. Like getting measles when you’re dying of cancer. A secondary disease.

I ate a lot of chocolate that evening, which led to regret, invention and decision. Feeling bad for the tired masses, I invented the band of hope, a hair band containing messages of hope to give to those in need of encouragement. I tried to blog it for my weekly craft, but because of a tragic home situation – dial-up – I gave up after an hour and concentrated on a life plan. Clearly, I could no longer not notice that my city is not only the epicentre of capitalist car-freaking-death culture but death itself, so, except for killing myself in spirit or body, there was one thing and one thing only to do: thrust myself into the heart of this evil. The Mall. I had to work in West Edmonton Mall.

The next day, I almost scored at Second Cup, thinking unlimited free coffee, yes. But Manager Rachel said I had to buy a Second Cup T-shirt for $27 and couldn’t use the espresso machine until I proved myself because the espresso machine was a privilege, not a right. When Roberta at Winners talked to me, I did not laugh at anything. It worked and I was unpacking Christmas ornaments with Tamsin before noon. Winners was perfect.

You can tell yourself nothing matters blah blah, but when most people keep going to school et cetera there’s this little bit of am-I-crazy-or-are-they. Maybe, you think, I have to tell myself nothing matters because I’m a loser. Winners clears everything up. When you’re unpacking big Christmas balls the size of your head and covered by some heinously strange feathers you can’t imagine a bird for, made by exploited workers in China, you know something is dreadfully, unspeakably wrong and then when you see people shopping and buying the big feathered balls in September for $16.99, well, civilization is sucking on fumes, isn’t it? So you look at the shopper and think a quiet I’m so sorry but good for us. You’re nuts for buying it, I was nuts for unpacking it, we’re all nuts, but we have each other. Tamsin asked me if I was Christian which was maybe an insult given her tone, but who cares – I was a caring person to a public in need.

Every morning I’d use the phone in the back to impersonate Joan and call the school, and I’d get home in time to erase the automatic where’s-your-kid message the school sent every day. For two weeks it was great. Then someone called Joan at work and she went all life-crisis. Thus ended my usefulness as a human. Leonard came to the house and sat across from Joan, me in the middle, Paige upstairs pretending to practice her handbells but actually only dinging psychotically whenever I said anything.

Parents wear you down with their worry and their guilt and their expectations. You look at your mother and you think, god, you turned your body inside out to produce me and you look at your father and, hell, he’s crying. Whatever, you try to convince them that crack, prostitution and living on the street in general do not interest you at all. But that’s where they go, they’ve seen the headlines and the movies. So, fine.

‘Okay okay,’ I said. ‘Yes, I’ll go back.’ Joan hit the table one more time to say this was about not throwing away my future, then went to bed.

‘Thanks a lot, Dad,’ I said.

‘Dree, you know how I hate to keep secrets.’

‘As in, hello, life is pointless?’

‘I’ve been putting away a little something for you every month.’

‘Yeah, right.’

‘For a couple of years now, surprise for the big fifteen. Listen, Dreebee, you’ve got to finish Grade 10. After that it’s the free-choice highway.’

I’m not an idiot. Not in the Leonard sense, anyway. He’d say what he wished was true instead of what was. I’d nailed him many times, told him not to make something look good just because he couldn’t stand the crappiness of it.

There was none of that and also, I gave him an out. ‘Really, Dad, you’re not just thinking about it? ‘

‘Two promises, Dree,’ he said. ‘One, don’t tell Paige or your mom; two, once you go, you call me every week.’

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘But Dad, it’s totally okay if this is an idea.’

‘Every month. Not a lot, but something.’

His voice was too quiet, his eyes too steady for a lie. At that moment, the special account existed.

‘So, Dad, how much is there, roughly?’

‘We’ll have the extravaganza treasure hunt. Coming of age and all that.’

‘Because, Dad, it’s hard to plan without a rough estimate.’

He could have used it up, that’s one possibility. Rita could have taken it. But it did exist. ‘Plan,’ he said. ‘You’ll have enough.’

I planned. I was up all night, and by the next morning the Plan was a beautiful thing. I’d go to Toronto, where I had blog friends, and find a way to live that wasn’t totally fake. Until then, I’d keep inventing stuff, making things, so I could get into the Renegade Craft Fair with Oxymrn who made $800 there last year with her retro aprons and beads.

So we made the deal, Leonard and I, and back I went. For the first time, I had a goal: to somehow use the futility of school as fuel for my blog, my crafts, my real life. For a while it worked, then I got incredibly sleepy. The school counsellor, Mr. Santini, was activated, and he was so worried about my lack of peer group I couldn’t stand his discomfort. ‘Whatever, fine,’ I told him. ‘I will make attempts.’ The film club was first, until Jeremy Mills said I had to wear spandex and get slathered in peanut butter because all film club members had to be corpses in his film on cockroaches taking over the world. Then came the anarchists, as in how adorable, anarchists in high school. Like vegetarians in McDonald’s. After the head anarchist’s girlfriend’s birthday party, that was all over. ‘Adolescence is deeply painful,’ I told Santini. ‘My way of getting through it is alone.’

He left me in peace since I was almost passing biology and art and had developed positive regard, as he put it, for Ms. Riddell, the biology teacher. Joan settled back down to getting people fired at work and Leonard stopped calling me every night for a report. For ten weeks, the Plan grew strong and glorious. I checked Toronto job sites every day and found a bunch of coffee shops that always need staff. I found a room in a house at Bloor and Dufferin, shared bathroom et cetera but who cares, and last week I sent them my rent and damage deposit knowing that today I would have the special account to pay Joan back before she knew she had been borrowed from. Six days ago, I registered for the Renegade Craft Fair, expensive but worth it, and of course I’d pay Joan back by the end of the week.

Five days ago, the Plan was poised to replace my meaningless life like an Academy Award presenter waiting to go onstage. Paige and I were in the Bio lab, partners because everyone else was partnered by the time we got there on Teeth Day – another tragic family situation being no dental plan. Aside from terror and pain, Teeth Day at the university student dental clinic means bus marathon which always means late. Since Paige is eleven months younger than me it is already unspeakable that we are in the same class, but she’s gifted, so who cares about my suffering. She had to be advanced a year and, five days ago, there she stood avec moi over dead fruit flies. Talk about foreshadowing. I had killed them with too much chloroform and she was displeased. ‘It’s easier when they’re dead,’ I told her. She had just said, ‘Correction? We’re supposed to chart their offspring?’ when the intercom crackled and our names were called. Paige tried to funnel the dead bugs back into the jar. ‘Get a move on, girls,’ Ms. Riddell said and I swung my bag over my shoulder, blowing the flies away. ‘Sorry,’ I said to them and Riddell.

In the hallway, Paige said, ‘It’s Dad.’ I was all of a sudden hollow, like a cheap chocolate Easter bunny caving in over a heat source. Leonard had already had two heart attacks. I used to be scared he’d die, used to imagine him dead on a stretcher every time I saw an ambulance or heard a siren. But since the Plan, no worries. Because Leonard was indispensable to the Plan, his death stopped being possible. I stopped at the trophy case with a picture of someone’s butt still taped to the corner. We could see Joan in the office with the principal. Paige pulled on my sleeve. ‘If we don’t move, it didn’t happen,’ I say. Paige pulled again. ‘C’mon, Dree. They see us.’