Читать книгу Summer in the Land of Skin - Jody Gehrman - Страница 7

CHAPTER 1 Learning to Taste

ОглавлениеI guess it’s obvious now that my father had some secret fatal flaw—a defect eating away at him somewhere inside his heart—but in the years leading up to his death I remember him as filled with the vigor of a yogi. His body was sinewy, long and lean, his hair a wild mixture of silver and brown spilling over his shoulders. Everyone agrees he was a genius; he built some of the finest, most intricate guitars in the world. I used to spend hours in his shop, caressing the stacks of wood that felt warm and alive under my small hands, putting my cheek against the cool mother-of-pearl. I would watch him patiently bend the rosewood sides over a heated tube, then clamp them into S-shaped molds to be sure the curves came out just right— “like a beautiful woman’s hips,” he used to say. I replay my memories of watching him work; I search his unguarded face, looking for clues. But he always seemed too alive, too otherworldly to be headed for such a seedy death. He had strangely feral eyes, dark as polished mahogany, with a visionary zeal so startling he could only be a god or a demon.

I think of those eyes as I tighten the focus on my binoculars, getting ready to study Magdalena. I do a cursory search of the others, skimming over their windows quickly—an exhausted mother changing her baby’s diaper, a young couple arguing as they gesture with shiny martini glasses. But the one I’m looking for is the slim, kimono-clad woman with raised bamboo blinds. There she is, on the third floor, watching the fog roll over the western hills. A single, flawless black braid snakes over one shoulder and her skin is so pale it makes me think of calla lilies. There is something in her eyes that always reminds me of my father—it’s the look that infants get when they gaze into the air with wild, unfocused bliss. Just give her a few hours, though. By midnight, she will stare out over the city with the hollow listlessness of a concentration camp inmate, a gaze that says she’s seen too much to go on looking.

I sketch her quickly in my notebook, and label it Magdalena: Manic as Usual. Then I spend hours jotting down notes about her childhood in Florida, her career as a flamenco dancer, and her inevitable suicide here, in San Francisco. She’s the type to slit her wrists in a bathtub. She thinks it will be pretty—all that red—like liquid roses.

I know I’m supposed to be somewhere tomorrow morning at seven. Namely, decaying in a lukewarm office before a computer screen, accomplishing data entry. But somehow I haven’t been able to move from this spot for days. I have a secret life here, wrapped in my beige apartment, recording the lives and deaths of my neighbors. Their bodies are real. Their histories—and their suicides—are all mine.

Maybe this is how it started with my father. Genes are very tricky, you know, millions of random cells dividing in a state of anarchy. I could have easily inherited the fatal flaw, the firing synapses that led him to that Motel 6, left him staring blankly at the cheap, flocked ceiling, wet with his blood.

I know I will not sleep. I have insomnia. Like him.

This is how I pass the time. Watching other people trying to live.

It is early in the morning when my mother comes whipping into my apartment in her high heels and tasteful, butter-yellow pantsuit. She sees me with my head propped against the wall, binoculars cradled between my thighs. I am naked, except for the old army blanket I have draped over my shoulders. I have not slept in five days. Her expression tells me that I am a despicable sight. She stands there, her thumb hooked on the strap of her suede briefcase, and surveys me with the edges of her mouth twitching.

She tries to flip her hair away from her shoulder casually—a habit left over from when her hair was very long, though she’s worn it in a pixie cut for fourteen years now and there is no longer anything left to flip. She pretends not to notice herself doing this and comes to sit on the edge of my bed.

“Christ, Anna,” she whispers.

She can look very mournful in the right light, though it is her practice to wear an optimistic smear of blush on each cheek and a precise smile, not too toothy, since there’s a gold cap next to her right canine. She takes a handkerchief from her pocket and reaches over to wipe a bit of sleep from my eye.

“Let’s get you in the shower,” she says. “Then we’ll put something nice on and go get breakfast. How does that sound?”

The muted morning light is resting on her face and hands, and the graceful curve of her neck is shining. I can recognize the fragile beauty my father must have seen in her—pale and vulnerable, with a dancer’s delicacy.

“You’re skin and bones. Let’s not talk until we’ve got you a nice omelette, a shot of espresso—”

“I’m not hungry,” I say.

Her hand seizes my wrist. “Listen to me,” she snaps, her eyes turned abruptly dangerous. “You will get in the shower now, do you hear me?”

“Jesus,” I say, and try to pull my hand away from hers.

“NOW!” Her jaw is clenched; I can see a vein at her temple throbbing rapidly.

“Okay,” I say “All right. My God.” This is my mother: fragile and sunlit one moment, pulsing with rage the next. I stand up, a little shakily, pulling the blanket around my body. “I’m twenty-five, you know, not ten.” I take a few steps in the direction of the bathroom, but everything seems unreal; I try to focus on my kitchen table, but the edges go blurry. I look up at the ceiling, the walls, the antique clock my grandmother left me. My legs become liquid, and a warm wave of nausea washes over me. I think to myself, Okay, then, I’m dying, and the thought registers something like relief before the room goes black.

I open my eyes and the world is filled with white tile, glass, and my mother’s face hanging over me, gaunt and transparent, like a ghost. The shower is on full blast, shooting ice-cold water at my solar plexus.

“Did you take something?”

I raise my head enough to view my hands, both of which look very distant. They are lying like dead fish in the shallow water of the tub.

“Sleeping pills, Valium? What?” she demands, pushing my hair back from my forehead.

“Nothing,” I say.

“You’re sure?”

“God, Mom, I don’t want to die,” I say, sitting up and reaching over to turn the shower off. “I just didn’t want to go to work.”

I watch as she pulls herself out of her crouching position, brushes imaginary lint off her pant legs and sits on the toilet. She rummages in her pocket and produces a pack of Virginia Slims.

“After Hours fired you. Did you get that message?”

I shrug. “You’ve been working on me to quit since I started there.”

She exhales impatiently. “I want you to use your degree.”

“Yeah. Big demand for anthropology majors.”

“I want you to use your mind, is what I mean. Data entry for a condom company is just not you, sweetheart. But this way you can’t even use them as a reference—that doesn’t help you move forward.”

Move forward. My mother is the queen of forward movement—with her sporty silver Fiat and her Silicon Valley life, where she drinks double espressos like water and occasionally sleeps with programmers visiting from Boston or Berlin. She hurls herself forward with the streamlined perseverance of a bullet train, but in her eyes there is a panic that is pure animal.

She smiles knowingly now and tells me, “Derek called yesterday. He said he was worried about your ‘stunted spiritual evolution.’”

I roll my eyes. “Derek. Jesus.”

“I told him, ‘It sounds like you’ve been dumped, buddy.’”

I’ve been with Derek for five years, and until recently I’d never asked myself why. He is thirty-six years old. He has an early-morning paper route to supplement the paltry cash he earns teaching meditation at a grubby little Buddhist center in Corte Madera. Now that we’ve broken up, I cannot even summon enough pathos to cry.

“Maybe it’s good,” my mother says. “A blessing in disguise.”

I can tell the cigarette cheered her up some.

“Maybe what’s good?”

“This little nervous breakdown you’re having,” she says. “Or whatever it is.”

“That’s great, Mother,” I say, pulling on some jeans. “Maintain your condescension, even in crisis.”

“Sometimes the only way to heaven is straight through hell.”

I stare at her. “What did you say?”

She looks up at me, startled. “What? What’s wrong now?”

“What did you just say?”

“About your nervous breakdown?”

“No. The other part.”

I watch her as she realizes her mistake.

My mother hasn’t spoken my father’s name even once in the fourteen years since he died. Very rarely, though, she will slip up and use an expression of his. My father had his own idioms—quirky phrases he repeatedly tirelessly. These words are buried in us, my mother and me, like tiny scraps of shrapnel.

She looks like a frightened child, now, caught in a lie. “Isn’t that funny,” she says. “I really don’t remember.” She flashes the precise, practiced smile that does not show her gold tooth. “I’m dying for some good coffee. How about you?”

Although my mother consumes on a daily basis the most exotic, trendy foods money can buy, when we’re together, she invariably insists on Josie’s, where the entrées jiggle under pools of grease and the espresso tastes like battery acid.

“Why do you like this place so much?” I ask. We’re standing in line to order, studying the menu, which is written in bubble letters with Day-Glo chalk on huge blackboards.

She glances around. “Some places just feel like home.”

Why my mother would feel at home here is a mystery. The place is filled with pierced faces and torn clothing, magenta shocks of hair and prominently displayed tattoos. My mother, sunny and fresh in her silk pantsuit, looks like Martha Stewart in a mosh pit.

We give our order to the girl behind the counter, a sullen, ungroomed thing with lots of beads knotted into her hair. Then we take our laminated number and find a table near the windows, where we wait in awkward silence for our food. I can tell my mother is aching for a cigarette. She keeps scraping at her cuticles like a nervous insect. They bring us our shots of espresso, and after she knocks hers back her face visibly relaxes. For me, though, the bitter brown syrup is a shock to my system; my mouth explodes with sensation. Five straight days without food or sleep have left me clean and high and empty; the world has a surreal pallor. The people and shapes of Josie’s move around me like an animated collage.

When our food arrives my mother orders another shot of espresso and digs into her ham-and-cheese omelette with embarrassing fervor. I raise a fork and touch the porous skin of my crepe. It gives under the blade of my knife much too easily, and something in my belly flips upside down.

“I know!” my mother says, talking out of the side of her mouth as she chews. “Suppose you took a class in computer programming?” She delivers this with a semblance of fresh energy, leaning forward like it’s an idea she’s just now hit upon, not the same suggestion she’s been making weekly for the past three years.

“Mother,” I say, my voice low with warning.

“But, no, I suppose you like data entry. I guess that’s your calling?”

“That’s over, now.”

“Oh, you’ll go groveling back there—”

“Don’t tell me what I’m going to do!”

We’re both surprised at how loud this comes out. A girl at a table near us glances over; she looks like a Rocky Horror Picture Show die-hard, and I resent her white face turning in our direction. I shoot her a dirty look and she averts her eyes. All at once I feel strangely powerful. I still haven’t even nibbled at my crepe, and I am floating on that weird, food-and-sleep-deprived hollowness that tastes like enlightenment.

“All right, Anna,” she says. “So you tell me. What are you going to do?”

“Sometimes the only way to heaven is straight through hell.”

“Don’t talk to me like that,” she chides, as if I have just cursed.

“What’s wrong with quoting my own—”

“I can’t,” she says, looking around helplessly. “I can’t do this.”

But I don’t want to stop—I’m empty and reckless, empowered by the sound of my own voice. “I’m not even living, Mom. I haven’t been alive for fourteen years.”

She gets up so suddenly that her chair knocks against the plate-glass window and her empty espresso cup topples over. She rights the cup quickly and snatches her briefcase. “I’m going outside,” she says, already moving toward the door. A muscular bike messenger inadvertently blocks her way for a moment, and she elbows past him, fumbling in her pocket for cigarettes.

Alone now with the crepes and the coffee, a calm comes over me, and the smell of food fills my head. I cut a piece of crepe with the edge of my fork and skewer a strawberry. I place the bite in my mouth carefully, like someone conducting an experiment. I chew slowly, and the flavors unfold with an intensity that shocks me; I can taste every seed inside the berry, every ounce of sweetness, the butter in the crepes, the eggs, the cream—it all sings on my tongue with a symphonic unity. For fourteen years, everything has tasted like variations on oatmeal. And now, suddenly, this wild thing is happening inside my mouth—a reminder of what it’s like to be alive.

That night I find myself sitting across from Aunt Rosie in the hip little Mission District dive she favors, The Boom Boom Room, where the lights are Chinatown red and the people all wear loud, retro-print shirts.

“I want you to know, kiddo, I think it’s just great you told your mother off.” Rosie is compact and feisty, with a bit of the bulldog in her. She has a boxer’s nose, thick, ungainly lips, and her body is built like a miniature tank, with almost no visible neck. She always wears platform shoes, and glitter on her eyelids; occasionally she is mistaken for a drag queen. “God knows she needed it. If Helen had her head stuffed any farther up her ass, she’d have to have it surgically removed.” She laughs at her own joke—one quick, staccato bark—and then looks unconvincingly contrite. “I’m sorry, kitten, I’m not here to badmouth your mother.” She takes a swig from her Miller Light. “She wasn’t always so uptight, you know. Back in the day, she was quite the party girl.” She rotates her beer bottle, a sad smile lingering on her lips. Then she sees me watching her, and looks suddenly self-conscious. “So anyway, what’s next?”

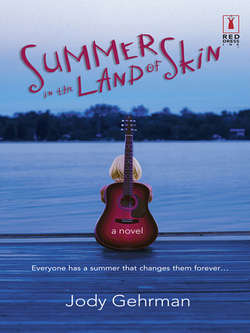

Without knowing I’m going to say it, I blurt out, “I want to build guitars, like Dad.”

She looks at me in surprise, then smiles. “Groovy,” she says. “Do you still play?”

I shake my head. “Not since he died. Mother didn’t want any music in the house.”

“Good God. That woman.” She takes off her pink fur coat and finishes her beer. “I don’t know why she has to be like that. It’s not good for you. It’s not good for her, either.”

“She acts like he never even existed.”

“I know,” she says. “It’s sad. I always thought it was sad.” She pushes my White Russian toward me. “Drink up, baby girl! You haven’t had a sip.”

I put the straw to my lips and suck a little of the sweet, creamy liquid. I’m not used to drinking, really. I’m not used to going out at all, lately.

“Well, I’m not surprised you want to learn the trade. You’ve got guitars in your blood. Your dad and Bender were legends.”

“Who’s that?”

“Elliot Bender. Old friend of your dad’s. They had a business for years—shit, they made guitars for Jerry Garcia, Bob Dylan, Bo Ramsey.” She looks around the bar dreamily, remembering. “They had a falling-out—everything fell apart. It was ridiculous, really.” She turns to me abruptly, her eyebrows raised high. “I have an idea,” she says.

It takes me one day to prepare, with Rosie’s help. I break my lease and fill my dad’s old leather backpack with four changes of clothes, ten pairs of underwear, a toothbrush, floss, and a notebook. I’ve got a thousand dollars to my name. Rosie insists on lending me her third ex-husband’s pickup truck. I leave my furniture and most of my belongings in her cluttered garage, with little hope of ever finding them again, buried in that sea of ancient trunks and stereo speakers, plastic shower curtains and milk crates full of yellowed photos.

Standing outside her old Victorian in go-go boots and a red chenille robe, Rosie cuts quite a figure in the chilly morning fog. It’s too early for her—seven a.m.—and it shows. Her hair is hectic with static electricity, and rings of mascara circle her puffy eyes. She yawns wide as she hands me an envelope and a carved statue of a Hindi god that fits in the palm of my hand.

“What’s this?”

“Shiva was your dad’s favorite—he took that thing with him everywhere. I figured you should have it.” I stand there on the sidewalk, fingering the smooth, cherry-colored wood, trying to imagine it in his hand. “Open the envelope later. It’s another good luck charm.” She smiles sleepily, and I hug her. “Now get out of here,” she says. “Before someone sees me like this.”

I forget all about the envelope until I’m in Portland, late that night, surrounded by the quiet gloom of a rest stop. I’ve been driving so many hours, when I rest my head against the steering wheel and close my eyes, I still see the road rushing at me. I reach for my backpack and take out the envelope, hold it in my hands a moment before opening it carefully. There’s a Bob Dylan quote scribbled in large, messy letters on the back of an ATM receipt. Kitten: She’s got everything she needs, she’s an artist, she don’t look back. XOXOXO, Rosie. I sit there, smiling in the dim yellow cast by the dome light, reading her words over and over, lingering on the urgent X’s and O’s. In the envelope is a crumpled one-hundred-dollar bill. As I pull back onto the interstate, I can feel a dull stinging behind my eyes, and I know if I weren’t so out of practice, I would cry.

On impulse, I get my hair cut in Seattle. I decide to let Ray, a high-strung man in a shaggy vest and leather pants, have total creative freedom with me above the neck. It takes hours, and there’s a lot of paraphernalia—intricate layers of foil, multiple applications of toxic-smelling goo. When he’s done, he spins the chair toward the mirror, and I barely recognize the girl staring back at me. I look like a 1920s starlet—he’s fashioned me in a chin-length bob, shorter in back like the flappers used to wear, and he’s highlighted my blond with streaks of bright gold.

“Girl,” he says, appraising me proudly, “I’ve really outdone myself today.”

As I’m driving the last seventy miles north to Bellingham, I tug at the rearview mirror now and then to look at myself. Each time, I’m startled by the strange woman staring back at me.