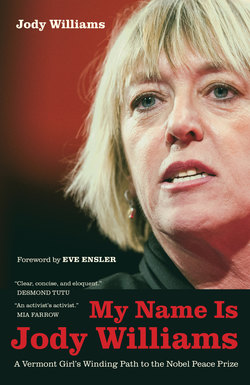

Читать книгу My Name Is Jody Williams - Jody Williams - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

October 10, 1997

The phone did not ring at 3 A.M. on Friday, October 10, 1997. It didn't ring at 3:15. It didn't ring at 3:30 either. If we didn't expect it to ring, we certainly hoped it would. But it didn't. Deflated, at least Goose and I could finally let it go and go to sleep. Since we'd finished cleaning the kitchen around midnight, we'd been tossing and turning in bed for hours.

We dozed off only to be woken up by the harsh ringing of the phone. I looked at the clock. It was 4 A.M. My heart was pounding. It was a combination of adrenaline from being startled awake and weird expectation. I picked up the phone to hear the singsong accent of a man who said he was calling from a Norwegian TV station.

He asked if I was me. When I said I was, he asked where I'd be in another forty minutes. As if I'd be leaping out of bed now and driving around the country roads of Putney, Vermont? I bit back any number of smart-ass retorts and simply said, “Here.” The phone went dead in my ear.

Goose and I looked at each other, wide-eyed and unsettled. Why had a call come at 4 A.M.? And why was it from Norwegian television and not the Nobel Committee?

Just a few weeks before, we'd spent a month in Oslo during the successful negotiations of the treaty banning antipersonnel landmines. Some of our Norwegian friends had told us then that the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, which I'd coordinated since getting it off the ground in 1992, was a front-runner for the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize. Media had buzzed about it the entire time we were there, even though we'd deflected their questions.

The last night in Oslo, we'd been out celebrating the success of the treaty negotiations. One of the Norwegian diplomats had whispered to us that if we were awarded the Peace Prize, we'd get a call from the Nobel Committee around 3 A.M. our time. They tried to give recipients time to prepare themselves before the chair of the committee made the announcement at a press conference a couple of hours later in Oslo.

But no call had come at 3 A.M. And when the phone rang an hour later, it was a cryptic exchange with someone from Norwegian television, not the Nobel Committee. Goose and I started speculating, and the only thing that seemed reasonable to us was that the media wanted to know where we were so they could get the ICBL's reaction to not receiving the Nobel Peace Prize after so much hype and expectation. Now we had about forty minutes to try not to fret.

The phone rang again promptly at 4:40 A.M. It was the same guy, who again identified himself as being with a Norwegian TV station. There was no dramatic pause, he quickly went on to say that he'd been “authorized” to inform me that the “International Campaign to Ban Landmines and its coordinator Jody Williams” were the recipients of the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize.

I repeated the words so Goose would know what was going on, then asked the guy who had authorized him to say that. He only repeated that he'd been authorized to let me know. He told me to turn on my television in about twenty minutes to hear the announcement live on CNN. I told him we didn't have a TV. “Well,” he said, “turn on the radio.”

When I told him there was no radio either, he laughed and said he'd keep me on the line so I could hear it directly from Norway. Stunned, I wouldn't be able to believe it until I heard the Nobel Committee say it out loud. I asked for about ten minutes to call my family. He said he'd call back then.

Mom screamed, “Hoo-hoo and yippeeee!” It was obvious she'd not slept any better than Goose and I that night. My father could sleep through almost anything. I asked Mom to call my sisters, Mary Beth and Janet, and my brother Mark to tell them to turn on their televisions and watch the announcement live. Then Goose and I waited until the phone rang again. We sat in bed with the receiver between our ears and listened as the press conference began. Francis Sejersted, then chair of the Nobel Committee, read the announcement, which captures the essence of our work in the Landmine Campaign:

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 1997, in two equal parts, to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and to the campaign's coordinator Jody Williams for their work for the banning and clearing of antipersonnel mines.

There are at present probably over one hundred million antipersonnel mines scattered over large areas on several continents. Such mines maim and kill indiscriminately and are a major threat to the civilian populations and to the social and economic development of the many countries affected.

The ICBL and Jody Williams started a process which in the space of a few years changed a ban on antipersonnel mines from a vision to a feasible reality. The Convention which will be signed in Ottawa in December this year is to a considerable extent a result of their important work.

There are already over 1,000 organizations, large and small, affiliated to the ICBL, making up a network through which it has been possible to express and mediate a broad wave of popular commitment in an unprecedented way. With the governments of several small and medium-sized countries taking the issue up and taking steps to deal with it, this work has grown into a convincing example of an effective policy for peace.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee wishes to express the hope that the Ottawa process will win even wider support. As a model for similar processes in the future, it could prove of decisive importance to the international effort for disarmament and peace.

I can't remember our immediate reaction when I hung up the phone, because we heard people outside. I crept to the window to see several cars parked in the driveway. Panicky, we threw on the clothes we'd taken off only a few hours earlier and went out to see who they were.

Journalists? The house sat at the end of a mile-long unmarked dirt road in the-middle-of-nowhere-Putney. We weren't prepared for them, and even less so for the onslaught that would follow. By 5:15 I was serving coffee to them in my kitchen. They were the first and last journalists we let in the house that day.

I was so thankful it turned out to be a glorious eighty-degree Indian summer day in Vermont. I kept wondering what we would have done with all the people if it had been raining.

By midmorning, the field in front of the house overlooking the beaver pond was studded with satellite feed trucks. Eight or nine of them. There were TV cameras dotting the field. On the deck. At my front steps. The day didn't stop, except for one ten-minute break, until the last TV truck rolled out at 8 P.M.

The interviews flowed from one to the next almost seamlessly. Journalists arrived from all of the morning TV news shows in the United States. From several in Norway, Canada, Sweden, and other places I can't begin to remember. There were some from several different shows on the BBC. We had local media. National media. International media.

All of them wanted to know how we'd use the Nobel Prize to pressure the Clinton administration especially, and other holdout states, to get on board. For the whole day we had media attention resulting from the Nobel announcement to further the message of the ICBL: Come to Ottawa. Sign the treaty. Ratify it as soon as possible. Join the tide of history.

I had no time that day to think about the course of my life and how I'd come to be surrounded by journalists, talking about antipersonnel landmines and the Nobel Peace Prize. No one would ever have predicted it. That a quiet kid from Vermont had become a hardheaded, straight-talking woman who'd helped change our world. But I did, and this is my story.