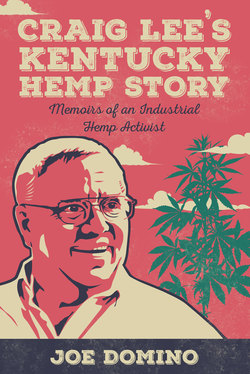

Читать книгу Craig Lee's Kentucky Hemp Story - Joe Domino - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Turner Heads

ОглавлениеIn 1996, a middle-aged Craig Lee was becoming a fixture at Kentucky’s county fairs. The county fairs are where the grassroots hold firm—a place where a vagabond hemp activist could reach people that normally, otherwise, couldn’t be reached.

I met and talked with people for hours, educating them on the virtues of hemp cultivation. I did so while representing the Kentucky Hemp Museum & Library, an initiative by the Kentucky Hemp Growers Association and Cooperative (KHGAC). I was a founding member of the hemp farmer cooperative and was, more or less, in charge of their guerrilla marketing. I wasn’t afraid to beat my chest and stand out. Advocacy is all about sharing ideas face-to-face; advocacy is not sitting on your Facebook regurgitating all that cow manure! If everyone shares the same ideas, then nothing ever gets done. Advocacy is about collaboration, hard work, and being present in the moment.

A wise man accurately described my feelings about advocacy and leadership in a single statement. It was a statement so important that he engraved it into a plaque and bolted it to the helm of his mahogany desk.

Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.

That wise man was Ted Turner. The next story is about my initial experiences with the Turner Foundation and how those experiences evolved from a grant opportunity into Ted Turner personally scheduling a meeting with my buddy and me—yeah, really!

For those who don’t know much about the Turner Foundation, their core mission was tackling large-scale international issues. They’re kind of a big deal. The foundation, just like it’s eccentric founder, quickly earned a reputation as being high stakes risk takers.

Before starting the foundation, Ted Turner wore many hats throughout his illustrious career. He was the founder of CNN (the first 24-hour Cable News Network) captaining the media empire for over twenty-years before selling to Time Warner Cable in 2000. Ted had a diversified portfolio of accomplishments beyond media too. He’s the diehard owner of the Atlanta Braves and, also, America’s first world sailing champion.

After living the better part of his life on the high seas, Ted decided to change gears toward saving the planet. And the foundation, driven by Ted’s lofty ideals, were not afraid to rock the boat. And, without a doubt, hemp was a controversial subject in 1996. The general public just couldn’t accept that hemp was not marijuana.

Those of us who were a part of the Kentucky Hemp Growers Association Cooperative (KHGAC)submitted a compelling proposal to convince the Turner Foundation that we shared their values concerning deforestation. We knew we could demonstrate that bi-annual hemp crops could be a feasible alternative to the insidious practice of clear-cut logging. Our pitch to the Turner Foundation was that the co-op would promulgate a new mode of agriculture to curb future deforestation. In addition to saving the world’s trees, we told the foundation that a paradigm shift toward hemp cultivation would increase revenues for struggling farmers as well fuel a new rural value chain. They loved the entire concept from the get-go. The Turner Foundation, impressed by our professionalism, financed our clear and concise corporate mission:

The Museum and Library Corporation was established to promote public education about the cultural, historic, and economic importance of the hemp industry in Kentucky and the United States.

The funds will be used to employ and support activities of a qualified curator; to obtain hemp implements, tools, machinery, industry artifacts, and books, photographs and other media descriptive of the hemp industry as it operated in the U.S. and as it now operatives in other nations; and to sponsor conferences and symposia on the use of hemp as a non-wood substitute for paper, construction materials, and other wood-based manufactured products. Grant Proposal submitted to Turner Foundation Inc. December 19, 1994

Over a three-year timespan, the Turner Foundation granted our small farmer cooperative $75,000, which covered the cost of outfitting the Kentucky Hemp Museum & Library Mobile Exhibit, traveling costs, and spending money to keep me fed while on the road. With our financial backing secured, I wholeheartedly carried out my end of the bargain: I educated the masses on the personal and economic benefits of industrial hemp. I traveled nearly 100,000 miles during my tenure operating the cooperative’s mobile marketing tank. Once on the open road, the KY Hemp Museum & Library Vanimmediately became the talk of the state. Our haters thought we had somehow pulled a fast one on the Turner Foundationand were in some way abusing the charitable tax code.

Others simply wrote us off as loose cannons. It’s fair to say that not everyone liked what we were doing. Many behind closed doors secretly hoped our “little fad” would die sooner rather than later. Nevertheless, our supporters saw real hope and were impressed by our rapid progress.

Before the Turner Foundation became our underwriters, I had been wandering the state like a mad cow in my beat-up white Chevy van. The old brute was getting craggy. My van wasn’t designed for all the hemp displays and artifacts that overflowed every time I opened the door. I was a laughingstock, although, I did my best with whatever was available. I tried hard to stand out amongst the fairs’ staple events: farming equipment, rodeo cowboys, circus acts, sheep shearing, cattle weighing, tractor pulls, jam and jelly tastings, and much more.

But standing out for the wrong reasons—like driving a ramshackle non-descript white van that possessed a worse reputation than hemp ever had—was not doing me any favors. My current ride wasn’t achieving the level of professionalism I had in mind. It was imperative that we stand out for the right reasons. I made known to the co-op’s board that our representatives needed to be properly equipped. Every day I gave a 110 percent effort, yet, I grew frustrated by how restricted my accoutrements left me. I needed the ability to amplify my limited energy. If we expected to win this war of propaganda, then we needed to improve our offensive firepower.

The Turner Foundation funding opportunity was discovered by Victor Mullens. Victor was the Marion County librarian. The library served as the Kentucky Hemp Growers Association Cooperative’s headquarters from 1995 to 1999. At the bequest of Mr. Mullens, the Marion County Public Librarygenerously donated an office space for the co-op to use. Not only did Victor help alleviate our operating costs, he also spearheaded the co-op’s grant writing. The Marion County Public Library was the perfect incubator for our start-up before start-ups were cool.

I first learned about the Turner Foundation after walking into our library office after returning from the state fair. The majority of the KHGACdirectors and founding members were present: Andy Graves, Dave Spalding, and Joe Hickey. They were mulling over an opportunity Victor found on the web recently posted by the Turner Foundation. Mr. Mullens caught me up on the good news. The Turner Foundation was a new and eager organization awarding large grants to ambitious environmental initiatives. The opportunity sounded perfect for the KHGAC.

Fast forward a few years to 1997: the Turner Foundation would make the largest private donation to the United Nations. A one-billion-dollar pledge establishing Ted Turner as the model billionaire-philanthropist inspired others like The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In collaboration with the UN, the Turner Foundation built solar-powered irrigation systems in Zambia, handed out mosquito nets to refugees in Kenya, and taught health care and nutrition to girls in Guatemala.

Yet, before marrying the United Nations, saving the planet’s trees was the foundation’s initial focus. The foundation announced their “Request for Proposals” to save the planet’s trees in the fall of 1996. The RFP called upon organizations—who weren’t afraid of thinking outside the box—to answer the call. The KHGAC knew we could save millions of trees by substituting hemp in one product alone, paper, not to mention cellophane, rayon, and a whole host of cellulose-based products.

We all agreed that what went inside the co-op’s final proposal had to coincide with our current grand idea: “PROJECT 23—the 1996 Kentucky Hemp Education Initiative.” The name PROJECT 23 was invented after the University of Kentucky polled citizens of the bluegrass state on whether they would support some kind of pro-hemp legislation. The results of poll showed that the majority of Kentuckians (77 percent) were in support of some kind of pro-hemp legalization. The crux of PROJECT 23was to convert the remaining 23 percent of non-believers. What the UKY’s poll indicated to us was that there was enough political momentum to steamroll the general assembly into legalizing industrial hemp.