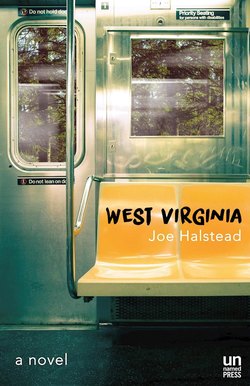

Читать книгу West Virginia - Joe Halstead - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

GROWING UP, Jamie’s best friend was Kenny Bennett. Kenny was a redneck and he talked about how he wanted to be one of the two toughest rednecks in school (“next to Adam Young”), even though he was kind of a pussy, even though they were all rednecks, and Jamie had a suspicion that Kenny wouldn’t let the aspiration go until he did something drastic.

It came at the end of seventh grade. Jamie was in a sleeping bag in Kenny’s backyard, drunk for the first time in his life, listening to Lynyrd Skynyrd, and he was feeling pretty sick and he tried to pretend that Kenny didn’t say anything, but then Kenny said it again: “Look at how big my dick is, everbody, quick, look.” He was in his sleeping bag and wearing a Mountain Dew T-shirt, Taco Bell sauce in the corners of his mouth, and his knee was pointed upward like a giant erection, and he pretended to masturbate, looking jumpy and excited, rubbing his knee boner, his eyes wide, a Dale Earnhardt hat stuck to the top of his skull.

“Y’all niggers have sapling dicks compared to me!” he cackled.

Tom Melvin, a “known faggot” among the boys because his hair was long and blond and his parents were college educated, was standing near the fire pit and he told Kenny to stop shouting “nigger” because it was the third time and a black person was going to hear him, and Kenny called Tom a dumb idiot because everyone knew West Virginia didn’t have any niggers, and then he asked Tom if he wanted to suck his dick and that he’d say “nigger” all he wanted, and Tom said no he didn’t want to suck Kenny’s dick because he “wasn’t a faggot,” and then a guy named Ben Patrick, a skinny fucker who thought himself a badass because his parents operated a funeral home and because he’d seen the naked corpse of the cheerleading captain who was killed in a car accident, laughed and said, “We gonna do somethin’, Kenny?”

“If Jamie’ll stop bein’ such a pussy,” Kenny said.

Jamie’s eyes rolled up. “Shut up, you fuckin’ little retard.”

Kenny sat on Jamie and started punching his head, and sometime after the fourth blow Jamie grabbed his arm and twisted it up behind his back but lost his balance, and they both fell to the ground and Kenny’s dog, Rocky, a black bull terrier, came up to where the boys were, but the fire was behind him and Jamie had to squint to see what it was.

“Rocky,” Kenny whispered.

Although Rocky was only five he looked older, and this was mostly due to the gunshot wound that’d mangled the left side of his head. He’d once been owned by the Bennetts’ neighbor, Carl Holden, who shot the dog with a .22 pistol. The bullet was deflected by Rocky’s skull and was lodged somewhere behind his ear. When Carl decided he couldn’t finish him off, he turned the .22 on himself. Kenny’s mother adopted the dog.

“Rocky,” Kenny said. “Let’s kill Rocky.”

Ben Patrick laughed and said, “You wanna kill your dog?” and even Tom Melvin started laughing with him and then Kenny said, “Let’s do it,” and then everyone got quiet.

Kenny had this dumb scary grin on his chipmunk face and he reached past Jamie into his backpack and pulled out some baling twine and a roll of M-88 firecrackers he’d gotten in Tennessee, and then he said that one of them would hold Rocky down and someone else would throw the firecrackers in his mouth and tie his snout with the twine. That was the plan. And suddenly Rocky was barking because Kenny was chasing him around the backyard, and Jamie groaned and got out of the sleeping bag again with the realization that he needed to prove something that night: that he could be just as heartless, just as cruel, as any boy from West Virginia. Kenny pinned Rocky and Rocky was moving his body around, trying to escape, and Jamie took the firecrackers and Ben Patrick handed him a lighter, and he didn’t want to see it when it happened so he turned his head and lit the firecrackers and threw them into Rocky’s mouth, and Kenny, laughing, tied Rocky’s mouth shut with the baling twine and then there was an explosion and Rocky was flipping around and his face looked like Daffy Duck after the exploding cigar and he was bleeding all over the grass. Ben Patrick said, “Oh shit,” and looked satisfied in a sad sort of way, and Tom Melvin started crying, and Kenny, still laughing, picked up a piece of Rocky’s skin from the grass and chased Tom around and then threw the tag of skin into Tom’s blond hair and Tom ran around trying to shake it out, and Kenny laughed, and Jamie’s hand was trembling and he tried to compose himself, and Ben Patrick looked over at him but he just looked away. He was about to leave when Kenny yelled something at him, and before Jamie knew it he was pinning Kenny by his sausage biceps and hitting him hard across the head and he wasn’t laughing anymore—he was crying—and after a while Kenny didn’t move and then Jamie sat there for a long time and watched Rocky limp off into the woods. Where he went Jamie didn’t exactly know, though he didn’t find it particularly hard to imagine.

The next night, Jamie and his father were sitting on the picnic table at the edge of the woods. The moon was huge, hanging low in the sky, pale, like the face of a sunken cadaver, and his father kept commenting on how big it was. Jamie knew that he’d heard about Rocky—his downward gaze whenever he came to the table told him so. They talked about it a bit, but Jamie couldn’t concentrate on the conversation because he had this feeling that they were being watched by something lurking in the woods, so he looked up and saw only one constellation: Orion the Hunter. Jamie looked up at him. He never changed, never moved at all.

“Was it you that put the farcrackers in the dog’s mouth?”

“All I did was hand Kenny the lighter,” Jamie said. “He was the one who stuck the firecrackers in Rocky’s mouth. Kenny came straight up to me and said, ‘Hand me the lighter.’”

“Why’d you hand him the lighter?”

“I don’t know. I guess I just couldn’t stand to see him actin’ that way.”

“Are you lyin’ to me?”

Jamie looked at him. All he said was “no” in a tone that made it clear he was lying. He wished for a moment he hadn’t lied. Even years later, he wished he’d told the truth.

“Should I believe what you’re tellin’ me? I always have, but now—”

Suddenly their dog, Scout, ran the length of his chain and was standing near them and barking in the direction of the woods. He’d heard something. They stared at the dark woods for a beat and then Jamie furrowed his brow slightly and tilted his head and then lay back on the picnic table, his face covered with his arm, pretending to be bothered by his stomach.

“Think I’m goin’ inside,” he said.

“What’s the matter?” his father said.

“I don’t feel good.”

“Are you sick?”

Jamie shrugged. Scout kept looking into the woods and then he started barking again. Jamie and his father turned around and looked back, and out near the end of the fence they saw a fawn chasing its mother along the fence, trying to nurse, as the mother ran afraid.

Jamie stopped talking to Kenny. He didn’t want to hear about Kenny anymore and tuned out when someone mentioned his name. Kenny was arrested for statutory rape once but then got out because West Virginia is a small place and something like that’d hurt families. Jamie heard he’d gotten married and worked in a coal mine. But he never talked to him again.

After he told the story, Laura talked to him without looking at him, as if absorbed by something invisible in the corner. She talked about work and he was nodding, but the words weren’t adding up to anything, like those books where people mark out all but a few words to create an enigmatic and entirely absurd poem.

“You sound a little nervous,” he said, “or something.”

“I sound nervous?” Her tone became harsh. “Maybe you’d like to tell me more about West Virginia and killing dogs, because you—I mean, I loved that.”

“OK, I’m sorry. I shouldn’t’ve told you that story, OK?”

“Well, yeah. I mean, I just don’t understand why someone would want to do that. Especially these days. I mean, it’s—you know—I just don’t see the point.”

“I know,” he said, frowning as he checked a text from the fashion design student: “just talked to Sara And she said it was cool and I think she just wants to talk and work it out,” and barely a second after it appeared he texted back “OK cool” and clicked off the screen.

Laura’s eyes were half closed and she was buzzed.

“Neither one of us wants to admit that something’s wrong with you,” she said.

Jamie sighed and leaned his head back and looked at his iPhone.

“You’re not a bad person,” she said, “but anyone who tells a story like that without thinking—I don’t know, you’re just seriously messed up.”

He laughed tiredly. “Seriously?”

“I think there might be something wrong with you.”

He turned to look at her face. He felt ashamed, as if something actually were wrong with him and this wrongness were obvious to the world. He decided he was going to give the rest of the conversation sixty seconds. He nodded thoughtfully, as if mulling it over, and then said, “They told me I could be like all the other redneck boys if I put the firecrackers in Rocky’s mouth.” He poured half a glass of wine and sighed. “So I keep that story in the back of my mind for one reason”—lighting a cigarette—“to remind me of who I don’t want to be.”