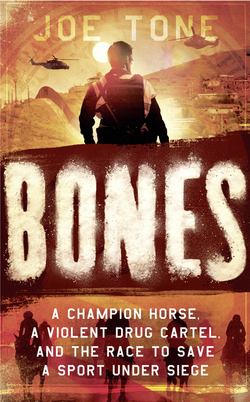

Читать книгу Bones: A Story of Brothers, a Champion Horse and the Race to Stop America’s Most Brutal Cartel - Joe Tone, Joe Tone - Страница 8

PROLOGUE POCKET TRASH NUEVO LAREDO, TAMAULIPAS, MEXICO June 2010

ОглавлениеAs he walked across the bridge that morning, approaching the invisible line that separated him from Texas, it wasn’t hard for José to envision what would come next: the welcoming American half-smile, the face-down scan of his passport, the keyboard pecking, the faux-polite please come with me, sir, and the pat down, always a pat down, before a waterfall of questions about his brother. He’d be lucky to get out of there by lunchtime.

It was only eight in the morning, but already it was 80 on its way to 101, with the sun preheating the pedestrians on the Gateway to the Americas International Bridge. “Bridge One,” as the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents called it, was the span used by the thousands of people who crossed by foot each day between Nuevo Laredo, in northern Mexico’s Tamaulipas state, and Laredo, Texas. José inched across, U.S. passport at the ready.

He was forty-three. He was thick through the chest and shoulders, soft in the middle, filling out his five-foot-seven frame. His black hair was thinning on top and fading at the temples; his round face was Etch-A-Sketched with proof of his status as lifelong laborer and father of four. He’d been trudging across this bridge for most of his four decades.

Crossing was once a breeze. Mexican or American, you could stroll across the bridge in either direction, the Rio Grande slogging beneath you, and through the checkpoint in a matter of minutes, often by just declaring yourself a citizen. It was the ease of crossing that made living on the border alluring: the ability to visit a favorite relative, attend a birthday celebration or quinceañera, play in a soccer game, or party in a country other than your own. You crossed the border the way people in other towns crossed a railroad track, so fluidly that residents referred to the two cities as one: Los Dos Laredos.

Over the years, though, the one-thousand-foot walk across had become excruciating, even for those who weren’t yanked out of line the way José was. It started after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when more agents were dispatched to keep the cable-news nightmares at bay. Armed with scanners, X-rays, and political consensus, Customs and Border Patrol agents, soon to be rebranded as “Border Protection” agents, started scrutinizing every crosser, looking for reasons to turn someone away. The line into Texas could take hours now, even if your name didn’t make the feds’ hard drives spin.

José made his way between the chain-link fence that lined this section of the bridge and the metal barriers that protected him from cars inching past to his left. At around five after eight, he finally approached the kiosk and handed the agent his passport.

Do you have any weapons?

No.

Do you have more than ten thousand dollars to declare?

No.

For years his answers had been good enough. Lately, though, when the feds scanned José’s passport, they got a notification from a proprietary security platform telling the agent there was some reason not to let José pass.

This time was no different. An agent escorted him into the fading beige U.S. Customs and Border Protection building. It was a maze of offices and interrogation rooms, connected by hallways with moldy tile and wheezy elevators that seemed forever on the verge of breaking down. The whole building smelled a little like a teenage boy’s locker. There were holding cells for criminals caught crossing, furnished with nothing but metal toilets and wooden benches, handcuffs attached and waiting. There were rooms for counting currency, equipped with computer terminals and scales. There was an intake center for families, mostly Central American mothers and children who were fleeing gang violence and hoping for asylum. There were dog cages but usually no dogs. They were all outside sniffing.

An agent patted José down and escorted him into an interview room. They called this “secondary inspection” or “hard secondary.” For José, a more apt name might have been a “We Know Who Your Brother Is, So Sit the Fuck Down for an Inspection” inspection. When José drove across, which was infrequent, they would comb his car and his person for guns, drugs, large amounts of cash, or anything else actionable. He had walked across this time, so they had to settle for what they called his “pocket trash”: the contents of a bag he was carrying and the pockets of his clothes.

Agents moved in and out of the room. They didn’t announce it, but José could guess what they were doing: making calls to whatever agency might have some questions about his little brother.

Thirty years before, when José was just a teenager, he had crossed this river on his way to lay bricks in Dallas. In time, people like him—Mexicans crossing north in search of work their homeland couldn’t provide—would be weaponized and dragged to the front lines of America’s culture war. But back then, for teenage José, it was as simple as crossing the bridge, driving seven hours north, finding a job, and going to work.

He laid his share of bricks in those early years. A few of his brothers did, too. They were constructing what could have been the foundations of a working-class American life. But before long, José was the only Treviño Morales brother left in Dallas. Now, as his wait on Bridge One stretched into its second sweaty hour, two of those brothers were dead. One was in an American prison. Another was enmeshed in Mexico’s trafficking business.

Then there was Miguel, the brother these feds so badly wanted to know about. He was a leader of Los Zetas, a criminal organization raking in hundreds of millions of dollars every year, much of it controlled by Miguel. Because of this vast accumulation of power and wealth—and because of Miguel’s unrivaled lust for mass, public, and grotesque violence—he was one of the most wanted drug lords in Mexico.

It had been this way for several years now. So for several years, this was who José was when he showed up at the border: the bricklaying brother of one of Mexico’s most wanted men. For all this harassment, José was never any use to the feds. He’d spent three decades as a mason; his callused hands had helped build Dallas’s exurban excess and then revive its urban core. No matter how hard the feds tried, they had never been able to connect brick-laying José to brick-smuggling Miguel.

But José was no longer a bricklayer, and that interested the feds. Recently, he had remade himself into a successful racehorse owner. He’d taken the racing business by surprise, quickly maneuvering into its upper ranks by hanging on to the fluttering silks of an undersized colt and partnering with a down-on-its-luck stud farm. Now, after winning a couple of big races, José was buying up some of the most expensive breeding mares in quarter-horse racing, the brand of racing preferred by the cowboys of the American Southwest and Mexico.

José’s new career opportunity had come just in time. In thirty years of laying bricks, he had never been able to do much more than keep his family afloat, even as his cartel-affiliated brothers in Mexico amassed cash, property, and power. Now his teenage daughter wanted to be the first in his extended family to finish college, with her three younger siblings hopefully not far behind. A few more breaks on the track and José might be able to pay for it all.

But his success at the track also made these crossings more titillating for the agents who swarmed these borderland interview rooms. Because however mysterious José’s little brother was to them, there was one thing they all seemed to know: Miguel loved horses.

About ninety minutes after José got pulled in, an agent from Immigration and Customs Enforcement showed up to ask all the usual questions.

I’m not proud of my brother, José said.

My brother has made my life hell, José said.

I don’t know where my brother is, José said.

He almost definitely didn’t. Few people knew where Miguel was at any given time. The moment people did know, his whereabouts changed.

At about ten-fifteen that morning, two hours after José had been pulled out of line, at least three since he’d stepped into it, the agents handed him back his belongings. There were some clothes, boots, toiletries, and a few coloring books and crayons, which he was bringing back for the youngest of his four kids. They were waiting for him in Dallas, and he was finally on his way.