Читать книгу Thomas and Rose - John Aitkenhead - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Four

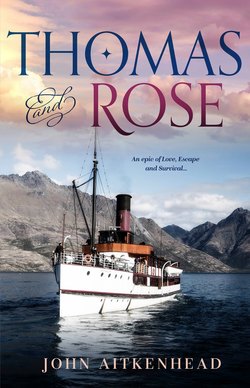

My dad told me that he needed to buy a merino stud ram, and we would have to travel to a sheep station aboard the steamship Earnslaw. We drove in the truck to Queenstown and parked in Ballarat Street outside Eichardt’s Hotel and close to the lake. I had convinced my dad that Skipper should come, and I was still really surprised that he had agreed. It seemed to me that my dad was trying to mend fences, and I was responding as best I could. My mother had sent a letter to school advising of my trip and asking for a day off. Mrs Baxter had agreed as long as I recorded everything from my day off and spoke to the class about the trip on the next school day.

My dad went off to buy our tickets and make arrangement for Skipper and the passage of the ram back to Queenstown. There were a few shops in Ballarat Street, including a milk bar with seats and tables down one side and a jukebox where you could put in money and play records. I walked back to the truck and let Skipper jump down. We walked down to the lake and out onto the jetty. There were two Maori kids – one I knew from school, Winstone Ratea – who were dropping bits of bread into the water. There were dozens of huge brown trout swimming below, and I could hardly believe my eyes when Winstone walked down the steps and caught one with his bare hands. I was relieved when it wriggled free and swam away.

I walked around to where the Earnslaw was berthed and ran into my dad on the way. Although it was early spring, there was still a lot of snow on the Remarkables, the wonderful range of mountains alongside Lake Wakatipu. We went aboard the beautiful old ship and put Skipper into one of several pens along with a few other dogs. I had brought along a notebook and a pencil and started making some notes to satisfy my agreement with Mrs Baxter. I found a brass plate on one of the walls with details of the Earnslaw and started writing:

In the late 1800s, a number of vessels provided access to isolated sheep stations around the shores of Lake Wakatipu. Demand for an improved shipping service led to tenders being let for the building of a new vessel.

A tender for £20 850 was accepted in 1910. Prefabricated in Dunedin, the vessel was dismantled and railed to Kingston at the south end of Lake Wakatipu. Reassembled in Kingston, the TSS Earnslaw was launched on the 24th of February 1912. In October that year, the vessel was officially handed over to New Zealand Railways Department.

Her details were:

Gross Weight: 330 tons

Steel Hull-Kauri Decks: 160 feet long, 24 feet wide, 7 feet deep

Engines: two 500-horsepower steam engines

Maximum load: 1035 passengers, 100 tons cargo, 1500 sheep, 200 wool bales or 70 cattle.

Crew: eleven

Speed: 13 knots

My dad went off to see the captain while I stood at a railing watching the furnace and the men shovelling coal into the flames. I understood how the boilers provided steam to drive the big turbine engines, but this was where my understanding ended, although I was fascinated by the way enough power could be generated to drive a big ship like the Earnslaw. We began to move, so I went outside as the ship gradually turned, disturbing a big flotilla of ducks and black-billed gulls, which took to the air. I walked up to the bow and watched the black smoke billow from the funnel as we built up speed. Although it was September, the wind was quite cold, and I did up the top button of my jacket and felt the wind ruffling up my hair. I went back to check on Skipper, who was having fun wrestling with a cattle dog in his pen.

I remembered Mrs Baxter telling us about the lake, which is 50 miles long and 1250 feet deep in parts. Because of its unusual shape, it has a ‘tide’, which causes the water to rise and fall about two inches every twenty-five minutes or so. She had told us about a Maori legend and the heartbeat of a huge monster named Matau, who is said to be sleeping at the bottom of the lake. The Dart River flows into the northern end of Lake Wakatipu, and the Kawarau River, beginning near Queenstown, handles its outflow. The lake occupies a single, glacier-carved trench and is bordered on all sides by tall mountains, the highest of which is Mount Earnslaw at 9586 feet. Settlements around the lake shore include Queenstown and the villages of Kingston, Glenorchy and Kinloch.

The Earnslaw steaming down the lake seemed both graceful and purposeful. The mountains rose up from the water’s edge with snow right down to the lower ridges and deciduous and conifer trees along the lake’s edge. Occasionally, we would see a farmhouse near the lake and sheep in the paddocks above. Twice, I saw some deer at the water’s edge. Eventually, a huge farmhouse and some very large farm sheds came into view as we approached the sheep station. We slowed down and came alongside a big jetty below the farmhouse. The crew tied up the ship and let down the gangplank. I went back to get Skipper and put him on his leash, which was required by the station family for dogs around the house and sheds.

Quite a few visitors and workers got off the ship, and a man called out to my dad. He introduced himself as Arthur, but I was told to call him Mr McKenzie. In front of the wharf was a big pen with a lot of sheep to be loaded aboard the Earnslaw; Mr McKenzie said 250.

Mr McKenzie took us for a look around, firstly to a big shed with two tractors, other farm machines and equipment. I was allowed to climb up on the biggest tractor and was shown how to start the engine; Skipper got a big fright. They were much bigger than our little Ferguson, had big steel wheels at the back and rubber tyres at the front. There were drums alongside the shed, which were used to store fuel for the tractors and for the big electricity generators. At the end of the shed, we went through a large door into a roosting area with about fifty hens and three roosters. The property needed to be self-sufficient as it was so remote, Mr McKenzie told us, although the Earnslaw and other Steamers were able to bring important goods.

We visited the woolshed, which was huge but empty, with the electric clippers hanging above the wooden floor. My mind quickly replaced it with the image of hundreds of sheep, and men in singlets busy shearing, as I had seen in magazines. I imagined the smell of sheep and sweating men, and even though it was imaginary, I was pleased to be back outside into fresh air.

The station had a herd of eighty cows and many thousands of sheep, a large orchard of fruit trees and a huge vegetable garden. So, as well as providing for its own requirements, it was able to sell eggs, chicken, vegetables and fresh milk to other farms. Women of the station made butter, cheese and soap, as well as sewing and repairing clothes for the family and the many workers.

Closer to the house was a line of six kennels housing the work dogs, which all looked very well bred and healthy. I let Skipper go up to each one and only one was unfriendly as it was gnawing on a bone and bared its teeth as we approached.

I hitched Skipper to a horse ring, and we went into the biggest house I had ever seen, going through the back door, and down a long corridor with rooms off each side, where the workers stayed. Then, we went into the massive kitchen, which had two huge coal range stoves – one with its door open so I could see the fire flaming inside. On each side of the stoves were large wooden worktops, each with a sink and a brass water tap, and above them were long shelves with tins and jars of many sizes. Two sacks of flour sat on the wooden floor.

A long wooden table with a bench on each side, like the ones in the church hall at Arthurs Point, stood in the middle of the kitchen. At one end of the table, there was a large porcelain teapot and several cups. Tea was poured, and a large lady with an apron asked me if I would like a glass of fruit cordial. I nodded politely. There were two bowls containing round wine and arrowroot biscuits, and another large lady with an apron was taking a tray of scones out of an oven. The second large lady plonked a bowl of floating butter balls onto the table followed by a bowl of jam and a second bowl with marmalade.

My fruit cordial wasn’t very sweet, but I was very thirsty, and I asked very politely if I could have some more. The second large lady frowned, then brought a jug and filled up my glass. The first large lady then put a tray of very hot scones onto the table. My dad whispered in my ear that I had better eat up because there would be nothing more until teatime. I had four scones loaded with butter and delicious jam.

My dad and Mr McKenzie had a discussion, and during the talk, there was mention of money. My dad unbuttoned a pocket in his trousers, took out a roll of banknotes and counted them out one by one. Our ram was in the pen with the 250 sheep, and Mr McKenzie said they were packed rather tightly, so the ram couldn’t conduct his business. He and my dad both laughed, but I didn’t quite know why.

A big clock in the kitchen said quarter to eleven, but the Earnslaw was not due back until four o’clock, so I asked my dad if Skipper and I could take a walk into the hills. My dad agreed but said I must look out for the Earnslaw, and as I would be above the lake, I would see it long before it arrived.

Skipper and I walked along a track leading to the milking shed and into a paddock with the entire herd of cows. There were also three enormous Clydesdale draught horses and a foal. One of the horses wandered over to us and nuzzled me with its huge head. Skipper looked unsure and whimpered, thinking it could harm me somehow, but I gave him an assuring pat. Then something really amazing happened. The foal came galloping over to Skipper, who ran off with the foal chasing. Then skipper chased the foal; and this went on for quite a few minutes until the foal was exhausted and laid down. Skipper lay down beside it, and I almost cried; I had seen something beautiful.

We walked on up the hill to a line of macrocarpa trees and a gate which we couldn’t open, so I lifted Skipper until his feet reached the top rail, then pushed him over the top, and he leapt down the other side. I then climbed over to join him.

We followed a long ridge with nothing more than tussock and the occasional plant they called ‘whitehairs’ or ‘vegetable sheep’. The ridge flattened out, and we were high above the lake with the farmhouse and sheds a long way distant. We sat down to enjoy the amazing view of Lake Wakatipu and the snow-capped mountains rising above. It was quite warm in the sun, and Skipper was panting, but we soon became aware of the air becoming colder as it clouded over.

Over the next couple of hours, we climbed several more ridges with magnificent valleys between them and fast-flowing streams flowing below, until we reached the snow. We came across a large waterfall with the water crashing down to a beautiful cascading stream, which must have been fifty feet below. We scrambled down through Raoulia shrubs and bracken into an area of flat bluestone rocks above a large pond. Skipper had a big drink, and I did the same with cupped hands. We then saw something amazing on the other side of the pond. A pair of Kakas – one of New Zealand’s two species of native parrots – and a juvenile were also drinking from the pond on the other side. When I stood up to get a better view, they flew up into a large mountain beech tree, squawking at us.

We followed the stream for quite a way and noticed the shadows on the mountains beginning to lengthen, so we climbed to higher ground where we could again see the lake. In the distance, we could see the Earnslaw steaming towards us. We could also see some of the buildings close to the homestead, so we set off downhill to be back in time to meet the old ship.

When we arrived back to the row of macrocarpa trees and the gate, I lifted Skipper, got him over then climbed back over myself. As we started back across the paddock with the cows and horses, I caught sight of my dad waving at us quite urgently, and I noticed that the Earnslaw had already docked.

The next three minutes changed my life.