Читать книгу The Ceredigion and Snowdonia Coast Paths - John B Jones - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

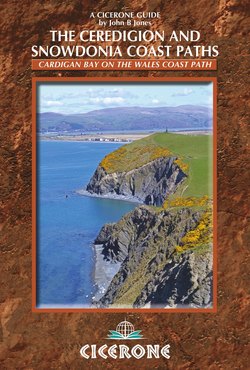

By turns rugged and gently contoured, sweeping and intimate, exciting and atmospheric, the coast of Wales down Cardigan Bay, from the end of the Lleyn Peninsula Coastal Path to the start of the Pembrokeshire Coast Path, makes for an inspiring walk. This guide covers the splendid and varied section of the Wales Coast Path along the Snowdonia coast, around the Dyfi Estuary and down the Ceredigion coast – a distance of 233km (145 miles).

A breezy day in the dunes of Morfa Harlech (Day 3)

The route follows long sandy beaches, high rugged cliffs and steep-sided cwms; you walk beside saltmarshes, stride over coastal plains, wander through the margins of Snowdonia’s coastal hills and crunch along pebble storm beaches. And there are great views: on clear days, especially from the central parts of Cardigan Bay, you can see the whole sweep of the coast from Bardsey Island to Strumble Head, backed by the mountains of Snowdonia in the north and rolling green hills in the south.

There are beautiful inland routes around the estuaries of Traeth Bach and the Dyfi, many attractive settlements to pass through and much of historic interest. A fascinating geology is laid bare in the different rock strata and landforms, and there is a rich and immensely varied natural history. While here and there the walk passes stark caravan sites, your abiding memories will be of a superb coast.

The Wales Coast Path/Llwybr Arfordir Cymru

On 5 May 2012 the Wales Coast Path was officially opened: a full 1400km (870 miles), from the outskirts of Chester in the north to Chepstow in the south, making it the first long-distance trail in the world to follow an entire national coastline. While the path incorporates existing coastal routes (including the Pembrokeshire Coast Path, the Lleyn Peninsula Coastal Path, the Anglesey Coastal Path and the more recent Ceredigion Coast Path), many new sections were needed. For the whole Wales Coast Path to have been created in such a remarkably short timescale is a magnificent achievement. Visit www.walescoastpath.gov.uk for more information.

Cnicht and the Moelwyns, as seen from the Cob at Porthmadog (Day 1)

The Llŷn to Pembrokeshire: the route in summary

The Snowdonia Coast Path: Porthmadog to Aberdyfi

This is not an official title but a name of convenience; since most of the route is within Snowdonia National Park it seems appropriate. The truly coastal sections tend to be along huge sandy beaches, while the remainder is through nearby hill country or across the coastal plains. Until you get to Harlech you would be forgiven for thinking you were not on a coast path, as the route takes you well inland via Maentwrog (although the new road and cycleway between Penrhyndeudraeth and Llandecwyn, replacing the unsuitable toll road, could be used as a shortcut). However, the Maentwrog loop is a fine wooded section, with great views of a number of the Snowdonia peaks. The path then – following the coastal plain of Ardudwy, via saltmarshes and fields to Harlech – reaches the sea proper. Alternating between sandy beach and inland routes, it arrives at Tal-y-bont. Rather than taking the official main road route to Barmouth, consider either an enjoyable beach walk (low tide only) or a fine hill alternative on part of the Ardudwy Way. South of the Mawddach Estuary the path lies back from the sea through hill country, a splendid section. It ends along the vast beach from Tywyn to Aberdyfi.

The Dyfi Estuary: Aberdyfi to Borth

A long inland loop through the countryside on either side of the Dyfi Estuary via Machynlleth (the lowest road crossing point) takes the coast path through beautiful hill country, with lovely views, returning to the coast at Borth.

The Dyfi, seen from the ridge road (Day 7)

The Ceredigion Coast Path: Ynyslas to Cardigan

Promoted by Ceredigion County Council, particularly in association with the Ramblers and Aberystwyth Conservation Volunteers (who assisted with much of the physical improvement work), the Ceredigion Coast Path (www.ceredigioncoastpath.org.uk) was funded under the EU’s Objective 1 programme for West Wales and the Valleys and was officially opened on 3 July 2008 by Jane Davidson AM, the Welsh Assembly Government Environment, Sustainability and Housing Minister.

The path starts at the flat lands at Ynyslas and joins the Wales Coast Path at Borth. Over a distance of just short of 100km (60 miles), it links Ynyslas with Cardigan (Aberteifi) on the Teifi Estuary, following some of Wales’ finest and most varied coast. It is quite different in character from the Snowdonia section: for the first time on the route there are extensive cliffs and the walking becomes much more truly coastal. The path runs magnificently over the cliffs to Aberystwyth and Llanrhystud, then an easy section along a narrow coastal plain leads to a long stretch of wonderfully rugged coastline, which is followed via Aberaeron, New Quay and Aberporth all the way to Mwnt before the way turns inland along the Teifi Estuary to Cardigan. The path follows many sections of pre-existing and often improved rights of way, as well as a number of specially created sections.

Cardigan to St Dogmaels

A short link on the south side of the estuary, via field paths and roads, leads to St Dogmaels and the official start of the Pembrokeshire Coast Path.

The Story in the rocks

One of the delights of the coast path is its ever-changing scenery, resulting from the varied underlying geology.

Between Porthmadog and a little north of Broad Water you encounter the oldest rocks along the path. These are called greywackes: hard, dark sandstones, alternating with softer slate and mudstones, formed 544 to 510 million years ago during the Cambrian period. Folded into a dome (the Harlech Dome), much eroded since its first formation, they rise from the coast towards the Rhinogs.

Subsequently the landmass that included Wales drifted north some 3000km (1865 miles) from the southern regions of the planet. Mudstones, siltstones and sandstones formed during this time occur along the coast between the Teifi and Ynys Lochtyn near Llangrannog.

Between Ynys Lochtyn and Borth the rocks of the later Silurian period comprise great thicknesses of greywackes, formed in fast-moving currents. The larger sand grains would settle out first, with finer muds on top, a sequence repeated many times and seen in layer upon layer of alternating strata in the cliffs. Most striking of all, between Cwmtydu and Borth, are the so-called Aberystwyth Grits, nowadays considerably contorted as a result of mountain-building forces.

An outcrop of Aberystwyth Grits at Allt-wen, south of Aberystwyth (Day 9)

South of Tal-y-bont to Llanaber, the path runs over much younger clays, silts, sands and gravels formed a mere 55 to five million years ago.

The land we see today has been modified by erosion and glaciation. As the ice retreated, and especially with the last retreat about 12,000 years ago, large amounts of glacial moraine and till were left behind, of such quantity as to overspread the low-lying coastal tracts. New stretches of coastal plain were formed, leaving former cliff lines inland. You can see this in the coastal strip between Aberaeron and Llanrhystud, for example. In some places the glacial debris is of such depth that it has formed its own coastal cliffs, such as at Llansantffraid. At Wallog, moraine forms the remarkable bank of Sarn Gynfelyn, stretching way out to sea, a survivor of thousands of years of tides and storms. Further up the coast, under the sea, lies the similar bank of Sarn Badrig.

At some places, such as off the coast of Borth, evidence of former land lies in the remains of submerged peat banks and old tree stumps still in their original positions, visible at low tide.

Undercut glacial cliffs near Mynachdy’r-graig (Day 10)

The processes of erosion and deposition are never-ending. We can see where the coastline is being changed today by the silting-up of the estuaries, or where marsh has formed and become vegetated, such as in the vast raised bog of Cors Fochno near Borth. And we can marvel at the huge dune systems formed in the last few hundred years, often as windblown sand has gained a toehold on the pebbles and gravels carried north up the coast by longshore drift.

History

Early settlers

By the time melting ice had finally cut Britain off from the rest of mainland Europe in about 5000BC, early colonists had already arrived on these islands. The first to leave visible evidence on the landscape, during the period from about 4000BC to 3000BC, were the Neolithic peoples. A number of Neolithic burial chambers are to be found in Gwynedd, a fine example being at Dyffryn Ardudwy. A number of stone circles, several near the coast, date from this time through to about 2000BC, as civilisation moved into the Bronze Age.

The Celts, who arrived in Wales from about 600BC, were warlike and had a culture steeped in legend. Their language (the various tribes speaking different versions of the same tongue) gave the basis for modern Welsh. The latter part of the first millennium BC saw the development of numerous hill forts, such as at Pendinas above Aberystwyth and at Pendinaslochdyn near Llangrannog.

Seen across a shimmering sea, Pendinaslochdyn appears in silhouette (Day 13)

The Roman invasion

The Roman invasion of Britain from AD43 made relatively little impact on West Wales. There was known to be one fort, near the path at Pennal, but roads were largely absent and the Celtic peoples carried on their way of life much as before.

After the Romans

The history of West Wales after the Romans departed is often shrouded in mystery. Irish tribes began to settle here; then, according to tradition, early in the fifth century one Cunedda and his eight sons came from Southern Scotland, subjugating the Irish settlers and imposing the Welsh (Brythonic) dialect of the Celts. It is perhaps no mere coincidence, then, that the conquered areas bear the names of Cunedda’s sons. Dunawd, for instance, is said to have given his name to Dunoding (an area that included the coast between present-day Porthmadog and Barmouth, the land of Ardudwy); Ceredig to Ceredigion, and Merion (the son of Tyrion, who had already died) to Meirionydd between the Dwyryd and Machynlleth. These are some of the oldest names in Wales.

At about this time, in the fifth and sixth centuries, there was a growth of monastic communities associated with powerful families, comprising a church and simple dwellings within an enclosure (a llan). Here religious men led a life of prayer and frugality. Along the route of the coast path the most famous of these men was Padarn at Llanbadarn (on the edge of present-day Aberystwyth), this llan later developing into the abbey and important bishopric of Llanbadarn Fawr. Many disciples who came to these llans went on to set up further churches, associated with the founder. Thus of the St David foundations there is Llan-non, named after David’s mother St Non, and Llangrannog, named after St David’s grandfather Carannog.

St Crannog watches over Llangrannog village (Day 14)

The Norman Conquest and the Wars of Independence

In the following centuries various attempts were made to create a wider unity in Wales, as, for instance, by Rhodri Mawr (844–878), his grandson Hywel Dda (c900–950) and others, but without long-term success.

A major change to the political map came with the arrival of the Normans, although in West Wales the conquest did not fully happen until the time of Henry I (who reigned from 1100 until 1135), when, for example, he gave Ceredigion to the powerful Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, who built the castles at Cardigan and Llanbadarn. In the succeeding centuries the history of West Wales is complex as various rulers arose to drive back the Normans, only to be overthrown themselves.

Among them, towards the end of the 12th century, was Llewelyn the Great, who by 1234 controlled all of North Wales. After his death Henry III once more took control of many of the Welsh territories, including Llanbadarn. But by 1257 Llewelyn’s grandson, Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, sought to restore the former position, notably in the two wars of 1276–1277 and 1282–1283. With Llewelyn’s death on 11 December 1282, defeat was on hand. The royal army advanced, taking, among other places, Ceredigion. Edward I, already building new castles elsewhere in Wales (as well as strengthening a number of existing Welsh castles, such as Llanbadarn) now initiated a further phase of castle-building, including Harlech Castle.

Houses of most of the monastic orders had come into Wales by now, paramount being the Cistercian house of Strata Florida, inland at Pontrhydfendigaid, under the patronage of the lords of Deheubarth and holding significant areas of coastal land at Dolaeron, Morfa Mawr and Morfa Bychan. Whitland Abbey in Carmarthenshire held coastal land at Porth Fechan (by Aberporth) and at Esgair Saith (by Tresaith). Cardigan and Llanbadarn were Benedictine foundations.

The Glyndŵr revolt

At Machynlleth the coast path reaches the place most closely associated with Owain Glyndŵr. He was born in around 1354, was well-read, spoke English, knew the legal system and became a soldier loyal to the English king.

Wales was turbulent in the 14th century, with much anger still emanating from Edward I’s subjugation of the country and from more recent swingeing taxes. The revolt arose from a local dispute with the English Lord Grey of Ruthin, who had apparently seized some of Glyndŵr’s land. The courts failing to back him, Glyndŵr took up the cudgels and, having been declared Prince of Wales in 1400 by the insurrectionists, first attacked Ruthin with some 4000 men, then moved on through Oswestry to Welshpool.

Machynlleth’s Parliament House is a Grade I listed building (Day 7)

Henry IV’s two expeditions of 1402 to quell the uprising, and the introduction of punitive laws, simply caused an escalation of the revolt. By 1403 Glyndŵr controlled much of Wales, and in 1404 he was crowned ruler of a free Wales in Machynlleth.

Glyndŵr, keen to form alliances with other sovereign nations, courted the allegiance of the French king and set out to demonstrate, in the Pennal Letter, his allegiance to the Pope in Avignon. But inexorably the Welsh were overcome, and by 1407 the rebellion was fading. Glyndŵr fled into hiding and died, it is believed, in Herefordshire in about 1416. He was unquestionably a man of vision, for had the rebellion succeeded some believe Wales could at that time have had its own church and university. However, the Welsh economy was left in a parlous state, and many churches and at least 40 towns had suffered significant damage.

This monument to Owain Glyndŵr stands in the park at Machynlleth (Day 8)

Henry Tudor

The next historic event of note along the coast was the progress through Wales of Henry Tudor (the future Henry VII). It was the usurpation of the English throne by Richard III, after the death of Edward IV (1483), which brought Henry into prominence. Landing at Dale in Pembrokeshire on 7 July 1485, and with considerable support from the Welsh, he made rapid progress up the coast, arriving at Cardigan on 9 August, Llanbadarn on 10 August and Machynlleth the following day, on his way to Bosworth.

The uniting of England and Wales

Under Henry VIII’s Act of Union of 1536, initiating the uniting of Wales and England into a single state, the boundaries of the modern shires were largely determined by those of the old Welsh divisions. Merionethshire included the coastal plain of the old lands of Ardudwy, while Cardiganshire (as the area was now called) conformed surprisingly closely to the ancient lands of Ceredig, son of Cunedda, a remarkable continuity down the centuries.

Second World War tank traps still line the beach at Fairbourne (Day 5)

Wildlife

The varied habitats found along the coast path – the cliffs, dunes, saltmarshes and woodlands, as well as the sea itself – support a wonderful array of plants and creatures. There are several nationally important nature reserves, and large tracts of the coast have been afforded special protection. Stretching 30km (19 miles) out to sea, the whole section from the Llŷn to Clarach has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation, as has the section from Aberarth to Cemaes Head in Pembrokeshire. The Dyfi Estuary has been designated as Wales’ only International Biosphere, with protection for the dunes, the extensive raised bog of Cors Fochno and other habitats.

Four sections of the Ceredigion coast (from Borth to Clarach, Twll Twrw to Llanrhystud, New Quay to Tresaith and Pen-Peles to Gwbert) have also been designated as Heritage Coast and are managed to conserve their natural beauty.

Offshore, Cardigan Bay supports an amazing variety of marine plants and animals, from bottlenose dolphins to the humble reef-building worm. Along the coastal margins, the sandbanks, reefs and caves are also hugely important for wildlife, with their attendant populations of grey seals and lampreys.

Sea pinks and birdsfoot trefoil are found along the coast path during the spring and summer months

From spring into summer a wealth of wildflowers thrives along the cliff sections of the path, including orchids, sea pinks, birdsfoot trefoil, thrift and bladder campion, with drifts of bluebells here and there. The common gorse is prolific, adding splashes of bright yellow to the landscape in the season. Butterflies also do well in these areas, and the cliffs are important breeding grounds for birds such as the razorbill, fulmar, guillemot and kittiwake, as well as gulls, and there are also populations of chough. Certain rocks are favourite places for cormorants to perch and hang their wings out to dry. You would be unlucky not to see red kite along the coast either side of Llanrhystud.

By contrast the shingle beaches may seem devoid of life, but a closer look will reveal plants such as the sea campion and sea holly thriving. The shingly flats near Broad Water, where the Dysynni reaches the sea, are a good place to see sandwich terns, eider ducks and turnstones, especially at high tide.

Large tracts of the extensive dunes, especially along the Snowdonia coast, are National Nature Reserves, owing to their rich wildlife (including orchids) and their butterflies, other insects and birds such as the shelduck and curlew.

The fragrant, bell-shaped flowers of bladder campion

The path crosses several areas of saltmarsh and runs beside estuarine flats such as those of Traeth Bach, the Mawddach and Dyfi – good food sources for waders and winter migrants such as redshank, wigeon and oystercatcher. In the Traeth Bach area look out all year round for the red-breasted merganser, and in winter for peregrine falcons, whooper swans and water pipits. Osprey have been breeding in the area for several years and you may be lucky enough to spot one diving for fish. The grasshopper warbler and common whitethroat can sometimes be heard around the Mawddach Estuary, and offshore from the Dyfi Estuary in winter you may spot red-throated divers, long-tailed ducks and the common scoter.

The various areas of woodland (found, for instance, in the coastal cwms and dingles) are locally important for wildlife, while much of the more extensive Maentwrog oakwood above the Afon Dwyryd has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation, supporting hundreds of species of mosses, liverworts and lichens, rare bats, and birds such as the pied flycatcher, redstart and wood warbler.

Commerce along the coast

The boatbuilding era

All along the coast (and especially south of the Dyfi) from the later decades of the 18th century and through the 19th century, boatbuilding was a thriving industry even in the smallest of settlements and least promising locations, as the roads were in a poor state and goods were often transported by sea.

Hundreds of vessels of many types, such as smacks, schooners and brigs, were built at this time and the economies of Cardigan, Aberystwyth and Aberaeron were largely based on this industry. The vessels plied their trade not just up and down the coast, but also across the Atlantic. Limestone and timber were major imports, and slate (especially from ports north of Machynlleth) was the main exported commodity. Wherever there was boatbuilding, so secondary trades went hand in hand, including rope and sailmaking, insurance and customs.

The advent of steam power, and of iron as a ship-building material, meant a decline in demand for the timber-built sail-powered boats; and the arrival of the railway, which enabled goods to be moved more easily by land, led to a wholesale demise of the industry. By the beginning of the 20th century it had largely disappeared.

The limestone industry

Limestone was a significant import in the 19th century. It was burnt in kilns to produce quicklime for use in building mortar, and for ‘sweetening’ the agricultural land; all along the coast – again, especially south of the Dyfi – there are limekilns, sometimes in quite out-of-the-way places.

A well-preserved limekiln at Cwmtydu (Day 13)

At the kilns the limestone was crushed, usually by hand, to a uniform size and built up into a dome, with alternate layers of coal inside the furnace on a grate above the ‘eye’ of the kiln (the air intake). The kilns were all roughly the same size, as this accommodated the optimum size of fire: any bigger and the coal and limestone would collapse under their own weight. Lime-burning was not only thirsty work but also unhealthy because of the smoke and fumes.

The coming of the railways meant that lime could be transported around the country more easily by larger manufacturers, so the small-scale individual limekilns became unprofitable and fell out of use.

The slate industry

Thousands of tonnes of slate per year were won from vast galleries in the hills of North Wales, particularly during the 19th and into the 20th century, with tramways and narrow gauge railways built to bring it to the coast for export. Serving the Rheidol Valley mines, a railway went down from Devil’s Bridge to Aberystwyth carrying slate and zinc. This is now the famous Vale of Rheidol Railway. From near Abergynolwen, slate from the Bryn Eglwys Quarry went to Tywyn on the Talyllyn Railway. And from the vast slate area around Blaenau Ffestiniog, the Ffestiniog Railway linked to the coast at Porthmadog.

Tourism

As the boatbuilding, limestone and slate industries declined, partly as a result of the arrival of the railway, it was the railway itself that prompted the growth of seaside resorts. Tourism remains a vital part of the economy of the area, based on its proximity to Snowdonia, on attractions such as the narrow gauge railways and on the magnificent coast.

A plaque near the Urdd Centre marks the official opening of the Ceredigion Coast Path (Day 13)

Walking the Ceredigion and Snowdonia Coast Paths

How long will it take?

Strong walkers could complete the full walk in just less than two weeks, averaging 22km (14 miles) a day. This would leave little time to wander through some of the settlements or visit the attractions along the way. Averaging about 16km (10 miles) a day, the walk would take you 15 days. It is also worth considering building in ‘rest days’ in order to visit, say, Harlech Castle, or ride one or more of the narrow gauge railways (see Visitor attractions, below). With conveniently spaced settlements, good links to public transport and available accommodation, the path could easily be broken down into shorter sections, giving time to explore and enjoy the scenery and the wildlife. For this you might need to allow about three weeks, possibly split between more than one holiday. It would also be perfectly possible to base yourself in one place for a few days and use public transport to reach the start of, and to return from, each day’s walk (see Appendix A and Appendix B).

How strenuous is it?

It is all too easy to underestimate the amount of climbing involved in much of the coastal walking in the British Isles. While long stretches of the Snowdonia Coast Path (being alongside saltmarshes or along sandy beaches) enable a fast pace, there are also some big ascents, especially between Maentwrog and Llandecwyn and on the routes out of Fairbourne and Llwyngwril, and also on the hill alternative between Tal-y-bont and Barmouth (Day 4).

The Ceredigion Coast Path is a surprisingly challenging walk overall, with many ups and downs and some big days, requiring a good level of fitness.

Walkers on one of the steep slopes north of Llanrhystud (Day 10)

Alternative routes: high tide routes and other options

At Borth and at New Quay it is possible to follow the beach at low or falling tide, and there are official alternative routes for when the tide is high. Between Cwmtydu and Ynys Lochtyn (Day 13) there is an official inland alternative for those who wish to avoid the exposed coastal path.

The beach crossing of the Afon Cledan near Llansantffraid on Day 11 can be difficult when the river is in spate: a short inland detour is available.

Between Tal-y-bont and Barmouth the official Wales Coast Path at present is actually along the main A496 for 4km (2½ miles), which is highly unsatisfactory. This guide gives an unofficial beach alternative (low tide only) and an unofficial and highly recommended hill alternative. For times of low tides useful websites are www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast_and_sea and www.tidetimes.org.uk.

Other suggested alternatives, where the official route is unsatisfactory, are between Minffordd and Penrhyndeudraeth, south of Maentwrog, at Harlech, at Tre’r-ddôl, near Tywyn and at Machynlleth. A short off-route detour is also suggested at Furnace.

Walking with dogs

The path passes from time to time through areas with livestock, through areas important for wildlife and close to cliff edges, so if you must take a dog with you it must be kept under close control.

Allt-wen from Aberystwyth promenade (Day 9)

When to go

Given the unpredictability of the British weather these days, there is no guarantee that you will enjoy more favourable conditions at certain times of the year, although on average the months of April to July are the driest (or should that be least wet?). Often, however, the coastal strip will be pleasant while the weather just inland is poor. From spring into summer, when the wildflowers are at their best, is also a good time to be walking the path. Some people may prefer early autumn, when the trees are just starting to turn. And while winter is unlikely to be a good time to be walking the whole path, a short section on a couple of well-chosen calm days would be rewarding if you are especially interested in the wintering birdlife on the marshes and in the estuaries.

In August – the high season for holidaymakers – accommodation in the main resorts can get booked up, so if this is your chosen time to walk the coast path it would be wise to book your accommodation well in advance.

Signposting and waymarking

The Wales Coast Path symbol is used between Porthmadog and Borth, while on the Ceredigion Coast Path the symbol generally used shows an outline of the headland of Ynys Lochtyn. On the whole the waymarking is good, but not foolproof; on complicated sections follow the route directions and the sketch maps closely.

(left) The buzzard is the symbol for the Ardudwy Way (Day 4; hill alternative); (upper right) A Ceredigion Coast Path waymarker; (lower right) A Wales Coast Path waymarker

Safety

Coastal walking is a great experience, but be alert to the dangers. Coastal conditions can be highly variable and can change quickly. Take extra care in high winds and do not venture to the cliff edge. Remember the coast can be subject to erosion and cliff falls. Follow any diversions in place. Check tide times in advance where the walk goes along beaches that are covered at high tide; use the alternative routes as necessary and note any possible escape routes. In an emergency call 999. Once connected to the emergency operator, explain the situation so that the appropriate service (Coastguard, Ambulance or Police) can be alerted, but be aware that mobile phone coverage is patchy.

Maps

The following OS maps cover the route in this guide:

Landranger: 124 (Porthmadog and Dolgellau); 135 (Aberystwyth and Machynlleth); 145 (Cardigan/Aberteifi and Mynydd Preseli); 146 (Lampeter and Llandovery/Llanbedr Pont Steffan a Llanymddyfri)

Explorer: OL18 (Harlech, Porthmadog and Bala); OL23 (Cadair Idris and Bala Lake); 198 (Cardigan and New Quay); 199 (Lampeter); 213 (Aberystwyth and Cwm Rheidol)

The extracts from the Landranger maps in this guide show the terrain immediately adjacent to the path. For the wider context the relevant Explorer maps are highly recommended.

The sketch maps, at a scale of approximately 1:25,000, show complicated sections of the path in greater detail.

For a short time the path follows the pebble beach south of Llanrhystud (Day 11)

Getting there

By train there are reasonable services from London Euston via Birmingham; from Birmingham itself; from Manchester via Shrewsbury and from the north of England and Scotland via Wolverhampton. All these trains go via Machynlleth, where the train divides – one part going on to Porthmadog (then Pwllheli), the other to Aberystwyth.

By coach there are routes from London, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow to Pwllheli for onward trains to Porthmadog, and a long-distance bus links Cardiff with Aberystwyth via Aberaeron.

To drive to Porthmadog from London and the southeast, use the M1, M6 and M54, the A5 to Betws-y-coed, then the A470 and A487. From the Midlands and the east make for the A5, then follow the route as above. From the Manchester and Liverpool areas get on to the M56, then follow the A55 coast road to Bangor and the A487 via Caernarfon. From the north and northeast of England and from Scotland, either travel down the M6 to join the M56, or travel down the A1 and join the M56 via the M62 and M6. To pick up your car from the end of the walk you can use one of the regular buses from Cardigan to Aberystwyth, then the train via Dovey Junction or Machynlleth to Porthmadog.

To return home by public transport from the end of the walk at Cardigan, use one of the regular buses to Carmarthen for trains or National Express coaches to London, the Midlands and further north.

See Appendix C for website details and telephone numbers of travel organisations.

For those travelling by air, Manchester and Birmingham International Airports are the best arrival points, both linked to the national rail network.

Getting around

Public transport along the walk is generally quite good. Regular buses and trains link most of the settlements along the coast, making it possible, with careful planning, to use public transport either at the start or end of a day’s walk.

A train leaves Tywyn on the Talyllyn Railway (Day 6)

Between New Quay and Cardigan, Ceredigion County Council’s coastal Cardi Bach bus can collect and set you down at convenient locations within a defined zone, and can be booked in advance. For a timetable go to www.ceredigioncoastpath.org.uk/cardi-bach.html or telephone 0845 686 0242.

There are railway stations at Porthmadog, Minffordd, Penrhyndeudraeth, Llandecwyn*, Talsarnau*, Tygwyn*, Harlech, Llandanwg*, Pensarn*, Llanbedr*, Dyffryn Ardudwy*, Tal-y-bont*, Llanaber*, Barmouth, Morfa Mawddach*, Fairbourne, Llwyngwril*, Tonfanau*, Tywyn, Aberdyfi, Machynlleth, Dovey Junction, Borth and Aberystwyth.

The stations marked * are request stops.

Accommodation

Appendix B lists places with accommodation (and type of accommodation available) at the time of writing, and Appendix C lists the tourist information centres relevant to the coast path. A useful website is www.visitwales.co.uk; for information specific to the Ceredigion Coast Path visit www.discoverceredigion.co.uk. An online search for hotels, guest houses and B&Bs in specific towns and villages is also a good way of finding somewhere to stay. For people who prefer to carry their accommodation on their backs, there are many official campsites (which are primarily caravan sites) along the coast; the list at Appendix B includes camping options. There are only two youth hostels convenient to the route in this guide: one at Borth and one at Poppit Sands (west of St Dogmaels).

Cab-a-bag scheme: luggage transfer

A luggage transfer scheme operates along the Ceredigion Coast Path, enabling walkers to forward larger bags from one overnight stay to another and carry a light pack for the walk itself. See the ‘Walking’ section at www.discoverceredigion.co.uk for further details.

What to take

As some sections of the walk are quite rough and rocky, and those across fields can be muddy at times, hiking boots rather than trainers are recommended. Always carry suitable wet-weather clothing, including lightweight overtrousers for rainy days and for when the walk goes through wet vegetation. A compass is unlikely to be needed (except on the hill alternative between Tal-y-bont and Barmouth) but do carry a charged mobile phone, noting that coverage can be very patchy. While there are frequent places offering refreshment, it is important to carry ample food and drink, especially in hot weather. And do not forget to take high factor sun cream.

Bright seafront houses at Borth (Day 9)

Visitor attractions

You may wish to build an extra hour or so, or an extra day as appropriate, into your walking schedule to visit one or more of the following attractions (listed here in the order in which you will encounter them):

The eclectic mix of buildings at Portmeirion (Day 1)

Welsh Highland Railway, Porthmadog – runs from the end of March to the end of October www.festrail.co.uk

Ffestiniog Railway, Porthmadog – runs from February to December www.festrail.co.uk

Portmeirion tourist village – open all year from 9.30am–7.30pm www.portmeirion-village.com

Harlech Castle – open March, April, May, June, September and October 9.30am–5.00pm; July and August 9.30am–6.00pm; November, December, January and February 10.00am–4.00pm (11.00am–4.00pm Sunday)

Fairbourne Steam Railway – runs from the end of March to the end of October, with limited days in February www.fairbournerailway.com

Talyllyn Railway, Tywyn – runs from the end of March to the end of October, with limited days in February, November and December www.talyllyn.co.uk

Owain Glyndŵr Centre, Machynlleth – open from March to the end of September 10.00am–5.00pm; and from October to the end of December 11.00am–4.00pm www.canolfanglyndwr.org

Centre for Alternative Technology, Machynlleth – open seven days a week, from Easter to the end of October, 10.00am–5.00pm www.cat.org.uk. (There are regular buses from Machynlleth.)

Ceredigion Museum, Aberystwyth – open Monday to Saturday, from April to September 10.00am–5.00pm; and from October to March 12 noon–4.30pm www.ceredigion.gov.uk

Vale of Rheidol Railway, Aberystwyth – runs from April to the end of October, with limited service in February and March www.rheidolrailway.co.uk

Dylan Thomas Trail, New Quay (see www.newquay-westwales.co.uk/trail)

St Dogmaels Abbey, St Dogmaels – open all year 10.00am–4.00pm (11.00am–3.00pm Sunday). There is an adjoining Coach House museum and café.

Using this guide

The route is divided up into day walks, each ending at a place with accommodation. The suggested sections are not written in tablets of stone and, based on the information in the appendices, you may opt to cover shorter or longer distances.

For each day walk an information box gives details on the walk’s start and finish points, length, amount of ascent and descent, overall time it might take, OS maps required, any opportunities for refreshments along the way, public transport and accommodation. Timings are based on the speed of a walker of average fitness, allowing for rest and refreshment stops and for the nature of the terrain. You will need to add in extra time should you wish to visit one or more of the attractions en route, such as Harlech Castle or a narrow gauge railway.

Each route includes extracts from the appropriate OS Landranger map. A number of sketch maps at a scale of approximately 1:25,000 are included to show the route in more detail over complicated sections. The maps in the guide are not intended as a substitute for the overall OS maps themselves, which walkers should also take with them. The 1:25,000 Explorer maps are especially recommended.

In the route descriptions key features that appear on the OS and sketch maps are shown in bold type to help with navigation.

In the appendices you will find a summary of the route distances and ascents/descents, and information on facilities such as places with accommodation, shops, cash points and where you can find a place to have lunch or an evening meal, and finally the addresses, websites and telephone numbers of useful contacts, including tourist information centres.