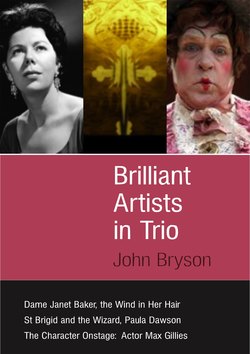

Читать книгу Brilliant Artists in Trio - John Bryson - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJanet Baker, The Wind in Her Hair

Dame Janet recently retired from public performance.

John Bryson recalls her visit to Sydney during the mid-eighties, when he took her sailing.

Here he profiles the great mezzo-soprano.

SHE WAS PLAYING WITH THE SOUND of the waves from the bow, it seemed to me, ‘Never before under sail’, she said. It was very close to song. The pitch was good. She had our precise rhythm. ‘Sometimes to sea, but never before under sail.’ So well did she know the behaviour of her own voice that she spoke softly ahead and we heard her aft, by way of the breeze. She was at the mast, ahold of the rigging, a scarf to guard the hair, a kerchief to shelter the throat. ‘Never before,’ her husband Keith said, ‘quite true.’ Keith was also her manager, and he looked nervous for her. She sang at concert in Sydney yesterday, and must sing again tomorrow. I called her to the cockpit, but she stayed where she was. She peered over her sunglasses. ‘Do you think I am fragile in my old age?’

She was barely fifty. Keith, with Tricia who was her publicist for this tour, and Roger Williamson who worked for her publisher, all seemed to know perilous things were afoot here I mightn’t yet have grasped. ‘No, Trica said, ‘you look fine.’ When she joined us, the scarf and the kerchief were gone to her pocket.

SHE BEGAN IN OPERA twenty-six years before, with the Oxford University Opera Club, Smetana’s The Secret, a chorus part. Within two years she had made it to principal singer, when Morley College called her to play Gluck’s hero, the bereft shepherd Orpheo. She was in mid-twenties. Another dozen roles, and she was onstage at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, the same year as New York first saw her. Since then she performed in forty seven operatic productions, many more if you count the solo concerts.

A few months back, she again played the role in which she was born as a principal singer in ’58, Orpheo ed Euridice. But now she was Dame Janet; now her following was so great that the season would command two theatres, Glyndebourne and the Albert Hall; now the orchestra before her was the London Philharmonic. Producers and music directors were her longtime friends, chorus singers were her acolytes, scene shifters left cheeky notes of praise in the dressing room.

Houses were packed. Again she was the boy Orpheo. In short-cropped wig, cape and leggings, she sang, danced, leapt. She found it difficult to stand through all the curtain calls. The company, in splendid array, gave her a bound letter from Berlioz to Viardot, the chorus gave her Orpheo’s lyre, the standing audiences gave her tumult. She had given to them the operatic performance of a lifetime, and the last of her lifetime. Tears were of admiration and farewell.

SO PRECIOUS AN INSTRUMENT is her voice that Keith was always in managing role, and keen she didn’t talk too much. This was effective for around an hour which, because the breeze was light, took us through a hamper lunch, of which she ate little but nibbled everything tropical, out of respect for things Pacific I supposed, but fealties like this are paid for by later fasts, and she said that if she couldn’t eat then she might as well talk, and she might as well do something. She had in mind taking the helm.

This was Broken Bay, Lion Island to seaward, to our left the inner head, its reef and ledges. She asked me to stand behind her until she had the hang of it. She was short enough that I had clear line of sight over her fluffing hair. As Donizetti’s Mary Stuart she had played to taller Elizabeths, and once ordered a pair of stilted shoes, but she threw them away, and worked on her presence in ways which had nothing to do with altitude.

The Hawkesbury estuary makes directly for the inland here, and we took this heading awhile, the wind over our shoulders. She had the rhythm of the following swell. Her small hands were firm and captainly, they understood the need for an authority in them. We rounded under the northern bluffs. The wind, from ahead now, was nudged about by the skewed cliffs. Roger asked if she wanted him to tell her what she might expect from this. She smiled. ‘I’d rather find out for myself.’ And she’d found something new already. ‘The wind isn’t only from the one direction, is it?’

YORKSHIRE HAS A FIRM PLACE in her understanding of herself, and when she speaks of something close to her heart she uses the accent of the north country. She speaks this way about her childhood and her parents. She seems to use these sounds in the manner of a musical score, to display that her family was of ordinary Yorkshire stock, at the same time as she demonstrates the skill and ambition of such folk, of whom she is a spectacular example. Alongside this is an uneasiness in her, about fame and success, which has to do with the distance between the small town of her birth and the footlights of the international stage. She is truly astonished.

To accommodate the magnitude of her journey she has set in place an intricate system of beliefs. She figures in them merely as the recipient of fortune. The simplest is a recognition of her astrological sign, which is Leo, and maybe accounts for her exorbitant capacity for work. Christianity contributes a good deal more, but is seemed to me that, of the Trinity, she attributes more to the power of God than to anyone, as if patronage like the this could come only from the mightiest source around. The third force, although she might dislike the heresy in putting it this way, the third force is deliciously pagan. She feels it in the theatre, she feels it in the voice, and in the most beautiful of music. When she sings beyond some already established pinnacle, which is always her goal, her heart swells in gratitude, and in awe. She is, as she sees it, a vessel chosen for performances like these, and whoever sequesters her at those times is nothing as puny as a muse. She is possessed then by no less than the life force of artistry itself, as old as the first song, fierce and intolerant of insult, no metaphor for the inexplicable here, but a terrifying and ancient being.

It follows that the gift may not be hers always.

SO SHE IS EVER AT RISK, and I made the mistake, asking if she regretted leaving theatrical opera. Keith sharply caught my eye, Roger and Tricia looked away. ‘I think I’m going fine,’ she said, appraising the course ahead, a generous ambiguity which saved me. She had given a third of her life to staged opera, and would give the next third to concert and recital. I supposed she saw the division between the dramatic stage and the recital platform the way scientists see their work in the applied or the pure, and priests the pastoral or the devotional. She would now devote to pure voice, and trust that the being which visits song will not turn its face from her.

Close to Lion Island a dory plied under a tempest of whooping terns, boat and birds together working a shoal of kingfish, most likely. We were heading for the open Pacific. She was humming a melody now, which Elgar wrote for the fourth of the Sea Pictures, under the words

It lures me, lures me on to go

And see the land where corals lie

which somehow put her better in mind of her task. ‘There’s holes in the wind, isn’t there? I don’t mean it blows then doesn’t blow, I mean holes in the wind.’ Indeed holes happen in the wind, in precisely the way she meant it. ‘And the wind changes its weight,’ she said, and she was quite right, gusts of identical speed may be much different in the way the boat feels them, a phenomenon I can account for only by variance of temperature and density. I know skippers who took a long time at sea to find an understanding of this.

Short of the headland we turned south, for home. The sun was cold and low. A seaplane landed its sightseers near the sand-spit at Palm Beach. The breeze was fading, so she spun the wheel this way and that, but we lay where we were. The water around us was slick and still. Keith broke out a bottle of wine from the locker, but she’d caught sight of a yacht which had a breeze of its own. I told her we’d have to wait awhile, which didn’t appease her for a moment. ‘If I was any bloody good as a captain, I’d have found us a breeze of our own,’ she said.

We made the wharf before dusk, and she seemed wearied but happy. Keith was concerned she might have overdone things, but by way of a trade-off of interests he said, ‘I suppose you’ll sing the Elgar now better than ever.’ She was already considered the best exponent of Sea Pictures, anyway since they were first presented by Clara Butt, with Elgar, in 1899, but more likely the finest of all time. She looked at Keith to see if he might be joshing. Slowly she said, ‘I don’t think that’s so daft.”

FULL CIRCLE, her account of her last year in opera theatre, was fresh in the bookstores then. In it she wrote of herself: ‘All that I am I owe to music. All that I will be, whatever it is, I shall also owe to music…’

Of her passionate Orpheo, and the way she plays him, she says: ‘Here I am as Orpheo, trying to find a part of myself, Euridice, who is lost to me. We all know what that means.’

HER CONCERTS IN SYDNEY were booked solid weeks before, so I spent that evening of her last appearance sitting alone on a balcony watching dories trawling nets for prawn between the islands of the harbour, listening to her performance broadcast, live, on ABC radio.

The works included Elgar’s Sea Pictures and, as the time came it seemed she took especial pause for composure, before some small gesture of assent allowed the conductor to tap the music stand, poise the strings and the clarinets, and begin the soft phrases of a gathering tide. The voice enters in the third bar, and from that moment it was clear she was in thrall. Not all the poetry in this cycle is very good, but the voice made it splendid, in squall defiant, in calm serene, phrases backed and filled before they were fully aloft, and launching her words to us, whole, in this tricky and inconstant air, seemed to require all the concentration she could find in herself.

When it was finished the audience hushed. I imagined Keith somewhere in a front row, a tear running his cheek, as happens whenever she excels beyond some previous mark, watching her make her bow under the sudden thunderhead of applause, she aflush and trembling, grateful to the being, whatever it is, who could now find her anytime, wherever she is.