Читать книгу Timeline Analog 3 - John Buck - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FRIENDLY’S DINER

ОглавлениеRon Barker quit his temporary office at Adams-Smith and moved home to research editing. He needed to raise money to go any further with the project and arranged to meet Chet Schuler who he knew had managed to get the Masscomp Computer project bankrolled.

The two met at Friendly's Diner in Sudbury, Massachusetts. Barker recalls:

Chet seemed like a very competent engineer and he had raised money. He convinced me he could help, so I asked him to put a financial plan together and manage the engineering team as well.

Schuler remembers the first discussions.

Ron had become an expert at his hobby of building and flying model helicopters and he had recognised that video editing was terribly cumbersome and counter intuitive and that if one tried to fly a helicopter by keyboard (for instance) it would be a complete disaster. He surmised that this created a unique opportunity for us to revolutionize the video editing process by inventing a more user-friendly product.

I came from an aerospace and computer technical/engineering background and had very little awareness of the practices of the video industry (which ultimately may have been to my advantage) causing me to express some reservations about this opportunity.

He didn’t know exactly what we were going to do, but he had an itch so bad he had to scratch it. It would not have happened if he hadn’t been involved. He was so bent on fixing what he saw as a hopelessly frustrating process, the linear online editing system.

With a home PC and dot matrix printer they formulated a business plan. Barker recalls:

Wang Computer had been successful with the Wang 1200 Word Processing System that was marketed as replacing typewriters with computer word processors, so I pitched an editing system that was a visual equivalent - a picture processor.

Barker and Schuler created a partnership that they wanted to call Picture Processor (PIP) but a quick search discovered a printing company Postal Instant Press already had the same initials.

Instead their new venture was christened Composition Systems Corporation (CSC) and included in its assets register Schuler's personal frame grabber, Barker’s Sony Betamax and his Sears monitor. Barker doggedly tested the theory.

I spent several weeks at the dining room table trying hundreds of picture setting combinations to finally determine that 4kb images were sufficient to "see where the star falls off his horse".

He tried unsuccessfully to interest West Coast based investors or business partners, so Barker changed his focus to the other hub of video editing in America, New York City.

John Storyk and Alex Major were the new owners of Metropolis Studios and I knew that they were keen to build the best studio production facility in the US and that they would benefit from being able to promote a state of the art editing system. So I wanted to solicit seed money in exchange for first delivery. Storyk recalls the meeting, vividly.

I can remember first meeting Ron, almost like it was yesterday. A meeting was set up for him to visit our offices on Union Square in Manhattan. Alex and I listened as Ron presented a well thought out presentation of this concept that Ron called 'picture processing'. We continued to look at each other asking the other (silently) if either of us had ever heard of anything quite like this.

When he was finished, we asked Ron if he could actually do this project. We believed him and agreed to inject $10,000 into this project, even though we barely had this money ourselves, but considered it a good investment. I remember having to actually lend Ron money at the end of the meeting for him to get back to Boston.

With money to continue working, Barker reconnected with Chet Schuler and the two men decided to set out on a research trip. Barker knew the solution to the creative impasse of electronic editing was to a visual interaction between editor and machine.

The user interface should be similar to the way he flew his helicopter, using eyes and ears but not looking down at the controls. Barker had also tested the concept of using the 'pause' function on his home Betamax machines to create in and out points, visually. He believed that there must be an existing method to combine both concepts for editing. Schuler recalls:

Ron decided that I should experience video editing from start to finish in order to convince me what a great opportunity this could be. First he explained the long editing process beginning with the editor reviewing his takes offline with burned-in time code while taking voluminous notes concerning their sequence, his preferences and all corresponding reel and time code locations in preparation for an expensive on-line session.

Anybody who watched an online session back then without any previous prejudices, like I was, just couldn’t believe how laborious it was and how expensive it was!

I was told before the session that it was costing the client over $500.00 per hour which (even though it wasn’t my money) made me feel very fidgety all though the long drawn out discussions concerning the time code locations of the edit entry and exit points for each edit point of the ad spot.

I guess because I was new to this entire field. I had no prior experience, no prejudices and so I looked at electronic editing and said to Ron, “This is crazy!” At one particular scene showing a skier making a wide showy turn in powder snow, there was a discussion of whether the exit point at location time code should be moved 50 or 75 frames forward or back causing me to whisper to Ron “

Why are they chatting in eight digit numbers to describe the particular image location they want to designate?”.

He started to explain rudimentary time code and I interrupted him. 'That's simple, I get it." What seems to be missing is that timecode number relates to a specific image, a specific frame, so why not have the computer use images of the frame in question to let the editor select his location of choice and have the computer keep track of the numbers, in the background.

Take actual timecode out of it and replace it with the images. There was a long pregnant pause after which Ron asked “Can you do that? To which I replied "of course, just digitize and store the images in a data base that cross references the time code locations and let the computer keep track of the editor’s time code choices”.

Schuler’s lack of familiarity with contemporary analog online editing proved to be an asset. Confident that there as a digital solution to the UI, the two men believed that video cards and frame stores could dispense with the need for a keyboard and timecode to guide edit decisions. Schuler recalls:

After the session we both became excited about this totally new approach to designing a video editing system, that was less a keyboard directed machine controller more graphical user friendly editing station adapted to the editor’s needs. The problem with existing editing systems was that the designers kept accommodating the existing technologies and their method was to make systems that made it easier for editors to access the technology without asking the question.

Is this the best way to use technology to assist the editor or would we better off, starting again?We wanted to radically shift the perspective from concentration on the machine activity and final Assembly quality, to the aesthetic and practical requirements of the editing process itself and have the editing system compile all of the necessary Edit Decision List (EDL) or film cut list information for a semi automated final Assembly process for any media.

The two men astutely realised that although videotape was replacing film in television production, it had tactile shortcomings. The editor could not 'see' the material he or she was editing unless they had electronic equipment, whereas their flatbed counterparts could feel and see film through their gloved hands. This they contended had 'dampened in some respects the creative talents of the director'.

Added to this fact was that editorial companies needed to employ non-editing personnel such as technicians or engineers to handle the workflow of video editing. Barker and Schuler contended later in their patents, that this inability to "react to the temporal nature of the media" was another hurdle to overcome.

They believed the new picture processor device could lessen the reliance on intermediate personnel, speed up the process and solve the time-space problem inherent in video editing. The two men sketched out a plan for the project which included of the following:

Ability to accept video, film, audio, timecode and film frame information for editing and output.

Secure “picture labels” or frame images for the beginning and end of all clips.

Provide multiple storage locations (bins) for organizing clips in logical groups for rapid random access retrieval in any order during the editing session.

Provision for a scrolling display of multiple image pairs representing beginning and end timecode locations (time code display could be turned on or off) any group of clips or any edited sequence of clips synchronous with or independent from audio.

Instant preview of any selected clip or selected sequence of clips.

Insertion of wipes, dissolves, fades or cuts of any length at any transition.

Complete freedom to change, rearrange and instantly view the result.

Create a clean EDL or Film Frame Cut List for final semi-automated Assembly when the editing session is finished.

Barker and Schuler knew that if these criteria could be implemented in the product they could revolutionize the industry. Their electronic editing system was to have the ability to change editorial decisions instantly, use pictures rather than time code as the cue for decisions and allow the editor to instantly view his/her decisions in real time. No more re-recording, dubbing, or losing generational picture quality.

Despite the richness of the idea, Barker was worried.

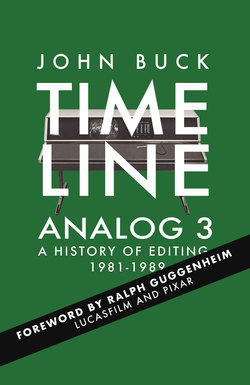

First, I suspected that Ralph Guggenheim’s team was already trying to solve the same problem. Second, if we wanted to continue this project, it would require further seed money to allow us to flesh out and test our product design concepts as well as develop a business plan so that we could acquire major funding to finance the team and resources to develop, build and market the product. It was winter and I had run out of heating oil from lack of funds.

Bob Doris was now General Manager of the Computer Division at Lucasfilm:

Greber and Faxon were charged with running Lucasfilm, not just the Computer Division which accounted for around 10% of the employees when there were no films in production and in single digits when films were staffed up.The other point worth noting that nobody in management was a technologist and nobody working on the projects had a grounding in business.

It was an interesting recipe! and in the early days a lot of fun and very interesting and I guess fascinating to see where we were headed. I was naive enough to think it was possible! My arrival was met with different levels of enthusiasm around the group!. But in general Ed Catmull and all of the leadership group was quite happy to have me around and seemed to get happier as I understood them.

Because I had been told “don’t ruffle feathers, keep them excited, keep them developing great stuff”.