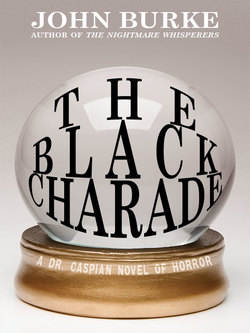

Читать книгу The Black Charade - John Burke - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

The chandelier in the coffee room of the Pantheon Club still showed the scars of last November’s outrage. Lacking one heavy cluster of drops and pendants, it hung slightly askew. Repairs could have been carried out at the same time as those to the window overlooking Pall Mall, but by tacit consent of all the members this relic of an historic moment had been left as it was, perhaps to remind them that in such revolutionary times they should never lapse into complacency. By the end of this century and well on into the twentieth there would be an accumulation of legends around that unsymmetrical chandelier: colourful fantasies of a night when a peer of the realm had been persuaded to swing from it and thereby bring down a portion in his fall; of a bishop who let a wine goblet fly from his hand in an impassioned appeal to heaven; even of a little-reported earth tremor. In fact, the crystal cluster had been demolished by a brick hurled through the window by one of the socialist marchers heading for Trafalgar Square on that bloody November Sunday of 1887.

The Right Honourable Joseph Hinde, Privy Councillor and Secretary of State for Municipal Development in Lord Salisbury’s Government, stood staring out of the window as if to raise the alarm should further attacks have to be repelled. A crossing sweeper, brushing steaming dung out of the path of a uniformed colonel on his way to a neighbouring club, caught a stab of the implacable stare and bobbed away round the corner, out of sight.

Viewed from inside the coffee room, Hinde’s stance had a different aspect. He had the air of one turning away in distaste from the two companions at his elbow rather than that of an alert sentry guarding the street. His always austere features were cramped with disapproval. Fellow Members of Parliament might have said there was nothing unusual in this: it was held by many, on both sides of the House, that the length and narrowness of his skull accounted for the narrowness of his opinions and the thinness of his voice. Here in his club, as so often in the House, he could not tear himself away from debate; but suffered by remaining.

‘A repeat performance. Invited to amplify the whole subject to the British Association in the autumn. Invited? Ha. Well-nigh commanded. What d’you think of that, Joseph?’

Sir Andrew Thornhill was mightily pleased with himself. His lecture to the Royal Society two evenings ago had been a success: that is to say, it had already stirred up a great deal of argument, which was always one of Thonhill’s aims. Hinde’s patent disapproval served only to provoke a mischievous pleasure in his restless blue eyes. He was heavier than either of his companions, with broad shoulders swelling beneath the spread of his cheviot coat, and a broad head weighted with a casque of silver hair, his side whiskers seeming to clamp it to his cheeks; but his eagerness and his constant wild gestures made him appear light and feathery, about to fly off across whatever room or platform he was dominating at the time.

‘The British Association,’ he repeated. ‘Hey, Joseph? A pretty contrast, hey, Caspian? There’ll be my estimable brother-in-law’—it was as if over the distance between them he were archly nudging an elbow into Hinde’s ribs—‘tramping the north giving speeches on traditional morality, whilst I demonstrate that all the old ideas are being constantly transformed into the new.’

‘Constantly distorted.’ Hinde did not look round, but could not suppress a dour response.

‘You weren’t even at my lecture, Joseph.’

‘We sat late at the House.’

‘If you’d heard what I actually said, you would realize there’s no question of distortion.’

‘What I’ve heard,’ said Hinde, ‘was that you’ve been preaching the possibility of the artificial creation of life.’

‘You see? False reports. Overstatement. I was talking about the prolongation of life. Quite a different thing. And why artificial? If it can be achieved within the natural order of things, then that makes it natural and not artificial, hmm?’

Hinde would not be drawn again. He moved an inch nearer the window.

Thornhill tried a wide conspiratorial grin at the third member of the group. ‘Don’t have to tell you, Caspian, a scientific man yourself, Etheric energy conversion: we all accept now that that’s what keeps us going. Energy can’t be lost. Can’t be created—there, Joseph, how’s that for an admission?—but it can’t be lost. And it can be refashioned. Always being refashioned. Nothing is destroyed, merely changed into another form.’ His right hand sketched soaring concepts in the air. ‘If matter and energy are indestructible, never suffering anything worse than conversion into another equally vital form, then human life is not a transitory thing.’

Dr. Alexander Caspian said carefully: ‘Obviously, the race as a race can continue to regenerate itself. The physical matter of our universe will change but cannot dwindle. One accepts that. But the prolongation of individual life...no, I’m afraid I have many reservations.’

‘Damn it,’ Thornhill burst out, ‘how can we ever make substantial progress if the best brains in the country are cut off in their prime?’

‘We make progress by drawing from what one might call a collective knowledge, amassed over the centuries. Each gifted individual is in fact gifted by his awareness of those sources and his ability to interpret them. The collective progress of the race and its philosophy—’

‘Damn collective progress! I want to see things for myself, and to go on contributing to them. Why should a man who has spent so long developing his skills have to give way, often at the height of his powers, to an infant who has to start the whole learning process all over again? If energy itself continues, why should not an existing formation of that energy continue? I’m convinced that the discovery of some regenerative process is waiting, just round the corner, so that those who don’t want to be transmuted into other matter may continue in their present shape, with their present faculties. And I want to live to see it. To see how our new knowledge is expanded and perfected.’

Caspian said: ‘Such desires are not new. And the knowledge is not new. This all-pervading ether to which you physicists ascribe the behaviour of all natural forces is similar to the Aksashic Record of Hindu mysticism. Paracelsus, too, wrote of just that astral power to which you have given a modern name.’

There was an odd hush. Caspian had half expected a burst of materialistic argument. Instead, Thornhill glanced covertly at him as if wondering what unspoken secrets they shared.

‘Perhaps,’ said Thornhill with unusual deference, ‘the old alchemists knew more than we like to admit.’

‘So that’s it!’ Hinde swung round. ‘Gibberish, just as I thought. Pagan superstition. A return to the Dark Ages.’

‘I meant merely that if we take those old concepts symbolically rather than literally, they often turn out to be remarkably close to what we’re now discovering by purely scientific experimentation.’

‘Such theories are bound to arouse opposition from some of your colleagues,’ said Caspian.

‘I expect it.’ Thornhill was gleeful again. ‘I could tell you here and now the names of enemies who’ll write scathing denunciations in Nature. And a lot of other places.’ He glanced past Caspian and raised a hand in greeting. ‘Speak of the devil. Or one of them. Old Walton—a bit restive the other evening. I really must go and find out what he made of it.’

He slapped Hinde on the arm and left them, eager for the stimulus of further battle.

Hinde looked grimly at a point somewhere in a vacuum, a yard or so from his nose. Then, slowly and stiffly, he said: ‘I was sorry to hear you encouraging his confusions.’

‘Confusions?’

‘Speaking of ancient charlatans such as Paracelsus in the same breath as modern science. All this Hindu nonsense, too: all the fakirs and fakements being inflicted on us nowadays.’ His bleached aquiline features were as unyielding as those of some Old Testament prophet. ‘So many of our current social problems derive from such rubbish. Such dangerous rubbish. That, to be frank, was what I was hoping to speak about to you. To consult you. Now....’

He was too polite to say he was already having doubts. Caspian waited. It would take the man a moment or two to bring himself to confide in a near stranger.

Then it came, hesitantly. ‘I am given to understand that you yourself take quite an interest in...ah....’ A longer hesitation, and a fastidious pinching of the words: ‘Psychic phenomena.’

‘In dispelling misconceptions about them, yes.’

‘I heard you exposed two fraudulent mediums a month ago. Admirable. Yet the gullible still attend the meetings of these abominable charlatans. People who ought to know better.’

Hinde’s lips were bitten in so tightly that they almost disappeared.

After a moment Caspian prompted: ‘You have someone particular in mind?’

‘I have indeed. I can trust your discretion, Dr. Caspian?’

‘If you have any doubts on that score, better not confide in me.’

Hinde stared full into his face. ‘I apologize. I would not have ventured to approach you if I had not heard the highest praise of your methods, from people I respect. And my own judgment tells me I can rely on you.’ He cleared his throat, still unsure. ‘A glass of wine, sir?’

‘When we’ve finished, perhaps.’ It was another gentle nudge.

‘Very well. Dr. Caspian, I am a widower. I had one son, killed in the Zulu wars. And I have one daughter, Laura. She is growing strange. I fear she has fallen into evil company.’

‘What company?’

‘She’ll not let me close enough to find out. But when I’m kept late at the House or some official function, I’m convinced she sometimes goes out on mysterious errands of her own.’

‘She has an admirer?’

‘There would be no need for her to conceal any such. She’s of age, it’s high time she was married. But she puts men off with that self-sufficiency of hers. Her mother encouraged her to be a bluestocking, and if I become too much the disciplinarian now, I fear I’d further estrange her. Since my wife died—’

‘Yes,’ said Caspian: ‘your wife. Couldn’t it be that the loss of her mother may have temporarily unsettled the girl?’

‘It’s more than a year now. And in. fact, at first Laura was a great comfort to me. But now she has taken to brooding. Her uncle’s influence on her—the way he talks, the meetings he addresses—none of it has been to her good. I wouldn’t put it past her’—the words were wrenched from him—‘to attend those infernal séances which are all the fashion, trying to contact the dead. She denies it: but so evasively!’

‘You haven’t considered following her? Or questioning the servants about her absences?’

‘She is of age,’ Hinde repeated, ‘and she is my daughter. I would neither humiliate her nor demean myself by chattering with servants.’

‘But you’re prepared to seek my intervention.’

Across the coffee room came a jubilant guffaw from Sir Andrew Thornhill. His voice rose in boisterous argument. With one accord Hinde and Caspian moved into the shelter of the pillared alcove at the end of the room.

‘You’re acquiring something of a reputation for dealing tactfully with—ah—odd cases,’ said Hinde. ‘Some way of reading people’s thoughts, they say.’

‘Do they, indeed?’

‘Only metaphorically, of course.’

‘Yes,’ said Caspian, ‘of course.’

‘Something you doubtless perfected in your career as a stage illusionist. “Count Caspar,” wasn’t it?’

‘And still is, from time to time. But domesticity has given me a taste for keeping my evenings free nowadays.’

‘I envy you. I wish that for me, too....’ Hinde broke off. For the first time Caspian caught a glimpse of a vulnerable human being behind that bleak façade.

He said: ‘Your daughter may simply be suffering from some extended fit of the vapours. That will either cure itself, or be more appropriately dealt with by a physician than by someone like me.’

‘Our family physician finds nothing wrong with her. Such disorders are outside his field. Nor will she confide in him.’

‘If we’re to meet, it must be done without arousing her suspicion.’ Caspian thought for a moment. ‘When is your birthday?’

‘In October. What has that to do with it?’

‘I was hoping Miss Hinde could be persuaded to have her photograph taken as a birthday present to you. But seven months away...no, that’s rather unconvincing.’

‘Her own birthday’s next week—the 24th of March.’

‘Capital. You shall ask her to sit for her portrait as a birthday present from you. Not quite as plausible as the other possibility, but she can hardly refuse.’

Hinde allowed himself a wry smile. ‘In her present mood she’s capable of saying she wants no such present. In any case, I fail to see what you’re hoping to achieve.’

‘My wife runs a photographic studio in South Audley Street. I shall be glad to make an appointment on your daughter’s behalf. People are very much off their guard when their picture is being taken, and in the most unobtrusive way we shall find what she has to tell us.’

He had only to think of Bronwen and he was already with her: she was at once so close that here in this male stronghold he felt it would be the easiest thing in the world just to put out his hand and touch her. Across the streets that separated them he seemed to detect the tremor of a response, the loving turn of a head and mind.

‘I’m in your hands, Dr. Caspian,’ Hinde was saying. ‘When shall I bring her?’

‘Monday at ten, say?’

‘She shall be there. And you’ll want me to remain?’

‘I should prefer you to occupy yourself elsewhere for at least an hour, and then call back for her.’

‘And you’ll report to me afterwards?’

‘Here or at your home, as you choose.’

Hinde took his arm. ‘Now, Doctor, for that glass of wine.’

As they emerged from the alcove and crossed the room, Thornhill flapped an affable hand. Only when they were out of earshot did Hinde quietly confirm: ‘Monday morning, then.’

* * * *

Laura Hinde stood by the lectern and listlessly turned over the pages of a portrait album, which Bronwen Caspian had opened for her inspection. It was bound in morocco, with gilt lettering on the cover to identify it as the property of The Powys Photographing and Enlarging Studio. Each page of heavy card had a gilt border, framing cartes-de-visite of sitters viewed from different angles and with different backgrounds. Some sat stiffly upright and stared vacantly ahead; others stood with one fist gripping the back of a chair, their gaze on some distant star. Clients usually arrived with little idea of the pose in which they wished to see themselves immortalized, and it helped to present them with a few samples.

Bronwen edged the mahogany tripod of her camera into position, and through the glass screen established a rough focus on the dais with its lyre-backed chair and potted palm.

‘If you care to try sitting beside the small table,’ she suggested, ‘or standing behind the chair, perhaps leaning forward—whichever you find most comfortable....’

Miss Hinde turned another page. She gave the impression of expecting no comfort.

‘I promise it’ll be painless.’ It was one of Bronwen’s stock remarks, usually arousing at least a wan smile.

The girl shrugged and turned towards the low dais. She sat down and folded her hands in her lap. Bronwen smiled encouragingly and rolled a tall cheval-glass on casters round so that the sitter could study herself. For a moment their two heads were caught in the mirror: Bronwen’s in the foreground, Laura’s remote and elusive, her eyes downcast. Not until some form of registering natural colours was perfected could such a contrast ever be satisfactorily captured. Hand tinting would blur and falsify their two contrasting heads: Bronwen’s auburn hair and wide, gently slanting green eyes; Laura Hinde’s flaxen tresses bound up too severely for her long, melancholy, beautifully moulded features, but still glowing with life in each fine silken strand.

‘We’ll have to see you more cheerful than that,’ Bronwen persevered. ‘I understand this is a present from your father. I’m sure he’d prefer it to be a happy one.’

Laura made an effort. ‘You and your husband work together, Mrs. Powys?’

‘Mrs. Caspian.’

‘I’m sorry. Of course my father told me the name was Caspian, but seeing Powys on that album, and over the studio door....’

‘It perpetuates my father’s name, and my own earlier work with him. My husband indulges me—allows me to carry on the work, and to keep the Powys name alive.’

The girl looked a trifle more animated. ‘What a fine thought.’ She raised her head, and the touch of a smile showed how ravishingly her features would be transformed if she smiled more readily, more often.

Bronwen stepped forward to indicate how the line of her arm across the pale blue dress would give balance to the picture, A tilt of the head to the left—‘And if you will just let yourself relax, just go slightly back against the chair’—and if only, she thought, she could be sure of catching the essence of that yearning, half-tranced expression. But even her slight intervention had turned the expression sullen and uncommunicative again.

‘Let’s try a couple of exposures, shall we?’ She took a couple of normal poses, then looped some drapery across a screen behind the sitter. ‘If you could lean back and look across at the far corner of the window....’

She tried to listen to the girl’s mind, but sensations were faint. A few shifting images faded and escaped. In her head Laura was as reserved as in her outward manner. But somewhere within the chill defences of her mind something fluttered: something fearful, like a timid animal peeping out of its burrow and then scuttling back to burrow even deeper.

The sensation intensified. For an instant Bronwen felt herself a hunter, strong and shrewd enough to draw the truth squealing and terrified out of the girl’s mind. The awareness was so strong that she knew Alex must be in the building. His mind had joined hers.

She removed a frame from the camera, suggested her sitter might care to consider some of the other poses in the album, and hurried into the darkroom.

He was perched on a high stool in the corner.

Quietly she said: ‘You can hear well enough?’

‘You know I can. I was with you. Try now. Listen with me.’

They were silent. Across Laura’s mind flitted a brief vision of a woman stooping, predatory, her head darkly veiled, two fingers of one hand jabbing an accusation. Then it was gone.

‘lt’s you!’ Caspian chuckled. ‘The wicked witch of the magic box!’ His lips brushed Bronwen’s cheek, and he said: ‘Do a few more studies, and we’ll both concentrate.’

‘Are you sure this is right? If she won’t confide in anyone, even her father or their own family doctor, of her own volition, ought we to eavesdrop?’

‘She’s crying out for help.’

‘If she won’t put it into words even to herself—’

‘Crying out for help,’ he repeated. His voice was no more than a whisper. At rare moments like this they talked as much with their thoughts as with speech. ‘But not knowing what help she seeks, she won’t tell all the truth. Even if she did try to confide in the family physician, she would tell him only what she could persuade herself to admit—which has nothing to do with her real ailment. We can’t refuse to listen—as much to what she’s not saying as to what she’s saying.’

Bronwen went back to the studio. The graceful head turned on its long, lovely neck.

‘You have some delightful pictures in this album. I’m sure the results of my visit won’t compare. Let’s not risk any further attempts.’

‘Your father’s not due for another twenty minutes. We really must do our best for him.’ Bronwen moved the camera into a new position. ‘Now, can we think of something cheerful? Or someone very dear to you? Or,’ she chattered on, ‘something that especially interests you? Now,’ she said sharply: ‘today.’

Caspian’s mind was in tune with hers. Both resonated to the conflict in the girl’s head. Through the thick mesh of the mental barrier she had erected they got a sudden clear picture of a newspaper advertisement. Then Laura Hinde rejected it again, virtually crumpling it up and hurling it away as if to cancel out anything it had said.

There was a dying whisper of words in that soft tone of hers, although she had not moved her lips.

Yes, I shall be there. To the end. I shall not fail.

The barrier closed again.

Bronwen felt her husband detach himself from her mind, like a lover withdrawing gently from her body. As ever, there was that pang of loss, even though at the moment he was only in the next room.

She took two more plates, and then said: ‘There, now.’

A carriage drew up close to the kerb, darkening the long window of the studio. As Mr. Hinde came in from the street, the back door slammed, and Alexander Caspian came along the corridor as if newly arrived. The two men shook hands. Laura stepped down from the dais and was introduced.

‘Doctor Caspian?’ She flinched away from him.

‘Of philosophy,’ said Bronwen lightly.

Mr. Hinde said: ‘A satisfactory sitting, Mrs. Caspian?’ His gaze ranged about the walls, and alighted on one of her father’s studies of Beaumaris. ‘If you should ever want to take pictures of my own establishment for your collection, please do let me know. I think it merits pictorial preservation.’

When father and daughter left, Laura’s head was bowed. Bronwen stood in the outer doorway watching. As they reached the carriage she saw Laura glance at Mr. Hinde, apprehensive yet wistful. But when he turned to speak to her, she was quite remote and withdrawn again.

* * * *

In the house Caspian had bought on Cheyne Walk immediately after their marriage, Bronwen sat facing him and said:

‘The type and setting of that advertisement belong to The Times.’

‘You plucked that from my mind.’’

‘Or you from mine.’

‘Oh, I think not.’

‘Really? You think not?’

‘I’ve just identified it, and you caught the gist of what I was thinking. Perfectly normal—for us, that is.’

‘And wouldn’t it be just as normal for me to think of a thing first, and you to register it?’

He laughed affectionately; and infuriatingly.

She said: ‘You’re so arrogant.’

But their minds drifted briefly together, and now they were both laughing.

Since the conventional wedding ceremony that followed their mystical union two and a half years ago, when they had pitted their interwoven minds against an engulfing force of evil, they had used their mental powers sparingly. At first the resources of telepathy, which they had so startlingly discovered within themselves, were a constant challenge, and a constant shared delight. But the strain began to tell. Too much energy, both psychic and physical, was drained away by too lavish a use of the faculty. It was too precious to be squandered on the conversational exchanges of everyday existence. And what need was there for it, when they could talk and take pleasure in the sound of each other’s voice? Bronwen loved her husband’s deep, musical, often mocking tone; and loved the movement of his lips when he spoke.

And then, complete surrender of the mind and its deepest secrets to another, no matter how passionately loved that other might be, was too destructive of privacy. Over the years it might even be destructive of the mystery and, paradoxically, the very intimacy of marriage. There were slow, sensual, mutual appreciations more rewarding than too direct an interchange of words or thoughts. And since what they shared was pleasurable and loving, there was no urgency. Thought transference was for times of stress: a telepathic message was an alarm signal rather than a leisurely comment.

London had added to the stress of using their gift too frequently. First learning its power and their own powers in a secluded Fenland village, they had communicated across the slow-thinking blur of country minds, hearing in the background what amounted only to a passing mumble, a half-formulated notion, with only the occasional harsh spurt of directness—until all those slow minds combined and unleashed a shared terror. The turmoil of the city was different, and dangerous in a different way. Prolonged mental exposure to its millions of unspoken desires and hatreds and confusions brought fierce headaches and a numbness of the mind: a cacophony of voices dinned unrelentingly in, clashing, some fast and some slow, too many shrill and disturbed and savage. Attempting to transmit a clear personal message through such discord was like trying to share confidences with a loved one and then having a window thrown wide open, to admit the full clamour of a screaming mob and the crash and screech and jangle of traffic.

Today they had exercised their powers briefly, but still found no neat answer to the question posed by Joseph Hinde.

Caspian settled deeper into his armchair. On the wall behind was Bronwen’s favourite picture of him: a portrait photograph which she had superimposed on a painting of a cloaked Mephistophelian figure rising above the Cavern of Mystery in Leicester Square. He had virtually retired from the theatre save for an occasional guest performance, preferring to devote himself to the exposure of fraudulent mediums and magicians rather than the display of his own avowedly, professionally fraudulent magic. Still she cherished the memory of him in his role of Count Caspar, in exuberant command of his skills and his audience.

Even in this room, at ease in his chair, he exuded the same power. He closed his eyes, but thereby became more widely awake. From memory and intuition he sought to call up whatever was relevant to that flash of insight they had experienced.

At last he said: ‘No, it’s an advertisement we’ve neither of us seen before. But we recognize certain aspects of it. So I feel it must be in a column adjacent to one of our theatre announcements. Logan will be able to trace it. I’ll go round and set him to work first thing in the morning.’

‘You can’t visualize the exact wording?’

Together they tried to bring the snippet of newspaper into focus from the remembered imprint of Laura Hinde’s consciousness. But only a few scattered words survived:

...TRUTH...death and its banishment... Scientific truth open to all who qualify as mature students... Thursday 12th January.

‘At least that date should simplify our quest. We’ll most likely find the item during the fortnight or so before the 12th of January.’

* * * *

The full version, when the Cavern of Mystery’s advertising manager had tracked it down, sat amid a whole batch of invitations to lectures and meetings: on two successive evenings the enquiring mind in search of self-improvement had a choice between the activities of the Empirical Society, the Paternoster Botanic Club, the Western Hermetic Society, and the Malthusian League, or a free discourse by Madame Helena Blavatsky on The Secret Doctrine. The one that Caspian had been seeking read, in full:

A DISCUSSION GROUP on

OUR INDESTRUCTIBLE LIFE

for discriminating seekers after TRUTH.— Lecture for serious Ladies and Gentlemen worthy of advanced tuition. The illusion of death and its banishment. ETERNITY IN THIS WORLD. Scientific truth open to all who qualify as mature students. Selection meeting Thursday 12th January at The Camden Lecture Rooms N.W.

Bronwen could see and hear it so clearly and depressingly: an hour or more of earnest disquisition in a dank and ill-lit hall, followed by equally earnest argument about Life and Death and the Hereafter and Scientific Proofs of something or other. Every night of the week there were such meetings and such jumbling together of hopes and frustrations all over London. ‘But why,’ she wondered aloud, ‘should Miss Hinde be so disturbed by her memories of that meeting—if in fact she did attend it?’

‘I fancy she attended it,’ said Caspian, ‘but yes, that’s our question: what did they teach her that proved so frightening...yet so irresistible?’

‘She won’t have been the only one to answer that announcement. There must have been others like her, hoping to get something from it.’

‘And perhaps, like her, now fearing what they’ve got.’