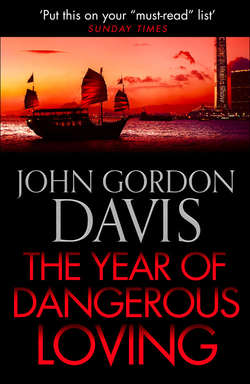

Читать книгу The Year of Dangerous Loving - John Davis Gordon - Страница 12

5

ОглавлениеAll the next week it seemed he could not get the image of her out of his mind. Her glorious nakedness, the sweet smell and taste and feel of her, and the memory of her standing at the immigration gates at the hydrofoil jetty that Monday morning, midst the clamour and jostling, the smells of diesel, of China, smiling all over her lovely face, her hair still wet from the shower, waving energetically: ‘Goodbye – goodbye …’ Hargreave went aboard the hydrofoil and slumped back in his seat. He could not wipe the smile off his face as he sat back in the air-conditioned first-class cabin skimming across the hazy South China Sea. And when the distant islands of the British colony loomed on the horizon, the myriad of ships from around the world at anchor, then the skyscrapers rearing up along the harbour front of Hong Kong and Kowloon, the most expensive real estate in the world with its mad money-making and its dense traffic and swarming people, it seemed he could not bear to wait to get back to sleepy little Macao next Friday, to Olga. He did not care what the weekend had cost him.

He disembarked at the ferry terminals, queued up to pass through the congested immigration barriers, then joined the sweating crowd along the walkway above Connaught Road. He hurried along the raised thoroughfares, past the marbled stock exchange with its fountains, where he had lost so much money the year before, past the elevated turn-offs to teeming Central with its hotels and shops and alleyways and towering business houses, until he descended through the crush towards Statue Square. Lord, give me sleepy Macao every time. Statue Square was teeming with pedestrians hurrying to work, cars and taxis and buses pouring out pollution around it. He hurried past the grand old Legislative Council building that used to be the Supreme Court, through the park that was the cricket club in the good old days, and crossed into roaring Queensway with its sweeping flyovers. Three hundred yards ahead the Supreme Court building reared up bleakly amongst the skyscrapers. He reached the basement parking area and rode up in the elevator to the first floor. He crossed the big atrium and entered the Crown Prosecutor’s chambers.

He was almost an hour late. There was the usual Monday morning bustle, his lawyers heading off for the courts in their wigs and gowns. He hastened down the long corridor, greeting his staff, and entered his chambers. There were several policemen waiting to consult him, and both his secretaries were speaking on telephones. He signalled to Miss Ho, entered his big office and closed the door. He slung his overnight bag on the long conference table and went to his desk. There were half a dozen telephone messages from policemen asking for an appointment, his in-basket high with files.

Miss Ho entered. ‘Good morning, Mr Hargreave.’

‘Morning, Norma. What problems?’

‘No problems, Mr Hargreave. Nobody sick.’

What a wonder! Over a hundred lawyers to worry about, and this Monday nobody was sick – it had to be a good omen.

‘Well I’m sick, Norma, sick and tired of this job, so treat me gently today.’ He slapped the pile of files. ‘I’ve got all this to read. Those policemen out there – send them to Mr Downes and Mr Jefferson and Mr Watkins, and if you’re stuck send them to Timbuktu.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Norma said, ‘but what about Superintendent Champion? He’s just telephoned for an appointment.’ She added: ‘The uranium case?’

Hargreave sighed. ‘Okay, I’ll see Mr Champion, but nobody else today.’

‘Where were you on Saturday?’ Bernie Champion complained, big and sweaty in his suit. ‘You said you’d be at the races. And I was going out for a Chinese chow last night, thought I’d invite you, I wanted to pick your brains.’

‘Which you’re doing now?’

‘Which I hope to do now. You look like death, where were you?’

Hargreave felt wonderful. ‘I was sailing.’

‘Like hell, your boat was in the yacht club all weekend, large as life. Who is she?’

‘I went to Macao.’ Hargreave smiled.

‘Macao, huh? Hope you wore a condom. How’s the chest?’

‘Healed very well. What’s the problem with the uranium case?’

Champion sighed. ‘Okay,’ he said, ‘you don’t want to talk about it, but I’m your friend and I’m asking you seriously, how are you?’

Hargreave hated this solicitude. ‘I’m fine, Bernie.’

Champion grunted. ‘Haven’t seen you around for a while, that’s all. Max, Jake and I, we were expecting you at the races, said you’d come.’ He raised his eyebrows: ‘And Liz?’

‘She’s fine too. She’s divorcing me, I got the letter on Saturday.’

Champion looked at him. ‘Divorce? I heard she was coming back.’

‘What?’ Hargreave stared.

‘Rumour at the yacht club. She phoned somebody and said she’s coming back, don’t know who. But listen, pal.’ He sat forward. ‘If you want her back, fine, I’ll play violins. But I’ve seen plenty of domestic strife in my thirty years in the cops, and if there’s going to be any more, don’t have the gun around. We nearly lost you. Imagine if she’d really hit you? You’d be six feet under and she’d be in jail. We don’t want that, for either of you.’

Oh God … Hargreave massaged his forehead. Liz returning, just when he was starting to feel he could show his face again? ‘She’s not coming back, it’s just a rumour. Her lawyer’s letter was only written last week, and it was very explicit.’

Champion said sympathetically, ‘And how do you feel about a divorce?’

‘Please, I don’t want to talk about it, Bernard. Now what about this case?’

The uranium case – Hargreave was sick of it. It wasn’t a case, it was a big amorphous file of theory and hearsay, mostly Investigation Diary reporting rumours which came to little. But it was Bernie Champion’s pet investigation. The only hard evidence was that a year ago the German police had arrested an elderly man called Wessels at Munich airport carrying a small sample of radio-active weapons-grade uranium in a glass jar. Enriched uranium is the basic ingredient in the manufacture of nuclear weaponry. Mr Wessels had just arrived from Moscow when he was arrested, and he had been about to board an aircraft to Hong Kong. He had refused to tell the German police how he had acquired the uranium in Russia, or to whom he was going to deliver it in Hong Kong: then, whilst being interrogated, he had died of a heart attack, leaving everybody none the wiser. The German police had sought the cooperation of the Hong Kong and Russian authorities. The Hong Kong police suspected that the notorious Chinese Triad societies were involved, intending to purchase large quantities of uranium to re-sell to terrorist organizations or warmongers like Gaddafi of Libya or Saddam of Iraq: but no evidence was uncovered, only rumours. A certain Colonel Simonski of the Moscow police had tried to trace the source of the uranium, without success: Russia was in chaos following the collapse of Communism but the government and all the personnel at nuclear sites insisted that none of their inventory had been stolen, every gram being accounted for and stored under tight security. Simonski had filed a detailed report to his superiors alleging, inter alia, that corrupt Russian bureaucrats were hand in glove with Mafia gangs to export nuclear material to Third World countries: he had promptly been removed from his post in the Organized Crime Squad and assigned to administrative duties. But his investigations were continuing, unofficially. There were some statements, forwarded to Champion by Simonski from Russian informers, who reported that this Russian crook had reported to this other Russian crook that this Russian bureaucrat at this godforsaken Russian nuclear plant had a deal with this unnamed Russian scientist who had not been paid his salary for six months to flog uranium for a staggering amount for export to Mr Gadhafi or Mr Saddam to blow us all to Kingdom Come in World War III. All serious stuff – but all hearsay.

‘So what’s new?’ Hargreave said.

‘Read the last page of the diary.’

Hargreave read it. More forgettable Russian names reporting rumours of a delivery of uranium to Moscow for shipment by air to the Far East.

Hargreave nodded. ‘Bad news. But where exactly are they going to ship it to?’

‘Right here,’ Champion said emphatically. ‘Hong Kong. Because we’re a huge duty-free port. For onward shipment to somewhere like North Korea, or the Middle East.’ He sat forward. ‘So I want your recommendation for more investigation money, I want to go to Vladivostok and Moscow and pay for information and get some statements from witnesses, so we can nail the Russian Mafia when they fly into Hong Kong. But the Commissioner of Police is worried this is a wild goose chase. However, he’ll allow me the funds if you recommend it.’

Hargreave was inclined to agree with the Commissioner. ‘But this is an offshore investigation so far, in Russia. How can I recommend paying out Hong Kong taxpayers’ money?’

‘Because,’ Champion said, ‘it ain’t offshore. Because when this stuff arrives in Hong Kong, who is receiving it, working with the Russian Mafia? The 14K. Terence Chang himself.’

Hargreave sighed. He’d heard all this before from Champion. Yes, everybody would love to nail the 14K, the biggest, strongest, nastiest Triad society in the world. And Terence Chang, the grand master. ‘But where’s your evidence?’

Bernie Champion tapped his head. ‘Trust me. Recommend the money and Simonski and I will get the witnesses’ statements in Russia, the plans for the shipment, who’s going to receive it in Hong Kong, the works. Then when that uranium leaves Russia we’ll do an Entebbe raid on the airport and catch everybody redhanded. Work backwards from there and uncover the whole murderous network – World War Three averted.’

‘Which airport will you raid?’ Hargreave demanded. ‘We don’t want radio-active uranium flying into Hong Kong!’

Champion said irritably, ‘How do I know which airport? I haven’t seen a Russian witness yet!’ He waved a hand. ‘Hell, man, this is the biggest, most important investigation imaginable – nuclear weapons to blow us all to smithereens, and you want to know which airport I’m going to catch the crooks at?’ He shook his fat face. ‘I don’t know, do I, until I’ve done the investigation with Simonski. But that takes money. Simonski hasn’t got access to police funds because he’s been removed from Organized Crime – and the Russian police have no money anyway.’

‘How much do you want?’

Champion pointed at the file. ‘It’s all itemized in there.’

Hargreave sighed. ‘Right, I’ll read the file again. But I’ll have to discuss it with the Attorney General.’

‘Why? You’re the Director of Public Prosecutions.’

‘Because he’s my boss.’

Champion snorted. ‘Notionally. Jesus, Al,’ he appealed, ‘can’t you see how important this is? Imagine if the Islamic Jihad or the IRA could build nuclear weapons!’

Hargreave put the file on top of his in-basket. ‘I’ll read it.’

‘How about dinner tonight?’ Champion said.

‘I won’t have an answer for you by tonight, Bernie.’

‘No, I meant just dinner. Haven’t seen you for ages.’ Champion looked at him appraisingly. ‘You need to get out of yourself, have some fun. You look exhausted.’

Fun? Hargreave had never had so much fun in his life – that’s why he looked exhausted. ‘Better not, Bernie, I’ve got a lot of homework to do and I need an early night.’

Which was certainly true. He was tired when he got home; all he wanted to do was have a few drinks and something to eat and hit the sack. But suddenly he was determined to do something about himself physically, to get into better shape. For Olga. So he went jogging.

He had not jogged for months and he certainly did not feel like it today, but he forced himself to do four kilometres round the mid-Peak roads, sweating in the sunset. It was agony but he kept it up. Olga was twenty-three, for God’s sake, and if he hoped to keep up with her he had to pull himself together, get some muscle-toning. Preserve the remnants of his youth. Tomorrow he would go to the gym. And he must do something about his diet – eat better: three meals a day instead of one and a half. He jogged doggedly to the supermarket at the bus terminus and bought some liver. He walked back to his apartment block with it. While the amah prepared it, he made himself go through the Canadian Air Force exercises that he used to do: press-ups, sit-ups, stretching. He was exhausted when he finished, sweating, but he felt good.

And virtuous. He showered, and he felt glowing. He looked at himself in the mirror. His pallor had gone. Forty-six years old – and she’s twenty-three. Oh, those breasts. Those legs. That creamy smile … You’ve got to get in shape or you‘ll just be another old guy trying to hang on to a young chick. No whisky this week – and get some vitamin pills tomorrow. He drank only two bottles of beer before dinner, and although he did not like liver, he ate it all. He went straight to bed afterwards. His last thought was of Olga, what she was doing. He groaned – he could not bear to think of her with another man.

The next morning he did more than buy vitamin pills, he telephoned Dr Bradshaw. ‘Ian, I want a tonic, can I come to see you?’

‘Sure, what kind of tonic?’

‘Something to give me a boost, I’m on a health-kick. Jogged four kilometres last night.’

‘Hell, take it easy,’ Ian said. ‘How do you feel now?’

‘Just fine. Stiff but good. And I want some advice on diet.’

‘Don’t overdo it on the exercise, we’re not as young as we used to be. What brought this on?’

‘And Ian – can you give me something to improve my sex-life?’

‘Hey!’ Ian said. ‘This is good news! Look, I’ll give you a course of vitamin B shots, but health is the best aphrodisiac. Good food – but watch the cholesterol. And watch the exercise at your age; don’t jog, buy a mountain bike.’

At his age. At lunchtime, instead of going to the Hong Kong Club for a beer and a sandwich, Hargreave went to the gymnasium near the Peak tram terminus, with Ian Bradshaw’s vitamin B shot buzzing in his system. He bought a season ticket.

It was years since he had been to a gym and he was not sure how to use all the equipment correctly, but he watched the next guy and followed suit. Lord, it was hard work. The gym was milling with sweating, muscled young men who knew what they were doing and Hargreave felt self-conscious: he was not flabby, but he was out of condition. And so pale – it was weeks since he had been sailing and he had lost his tan – and he wouldn’t be sailing this weekend, no sir. Then some older men came in, and he did not feel so bad – they were out of condition too. Then he felt worse – they knew how to use the machines, they weren’t sweating and puffing like he was. Hargreave watched them furtively as he doggedly slogged his way through the equipment. He was exhausted when he reached the end of the circuit, his legs and arms trembly. But by the time he got back to his chambers, after a hot shower and a nutritious lunch at the gym’s health bar, he felt great. He wanted to tell everybody where he’d been. Then the telephone rang.

‘A Miss Romalova for you, sir,’ said Miss Ho.

‘Put her through! Olga! Are you all right?’

She chuckled. ‘I am very well, except for my poor pussy. And my heart, my heart is very sore also.’ Hargreave was blushing. ‘Will my heart get better on Friday?’

‘Yes.’ Oh yes, he could not wait for Friday. ‘So your work-permit is okay?’

‘Yes, the police have extended for three months. And the big boss has agreed also.’

Oh, yes. ‘Well, I’ll be there on the seven o’clock ferry.’

‘Lovely! Which hotel do you want to stay in?’

‘The Bella Mar.’

‘So expensive. Why not another hotel, not so much?’

‘No, the Bella Mar.’ He had to have her in one of those airy, exotic suites, beauty like hers deserved the Bella Mar.

‘Shall I reserve? Maybe if I reserve I can get a small commission.’

‘Fine.’ Hargreave grinned.

‘I will give it back to you.’

‘No, you keep it,’ he laughed.

She seemed to accept that as reasonable. ‘I cannot meet you at the ferry, darling, because I must be at the club. But do not come there because then you must pay entrance, and the drinks are so expensive. Telephone me there when you are ready, and I will come to the hotel. But you will have to pay the bar-levy, I’m sorry.’

‘That’s all right.’ Talk of money made him uncomfortable.

‘But I will give you a discount for me, darling, don’t worry. And we will have a lovely weekend, I promise.’

Hargreave grinned, blushing: ‘And I promise you.’ He wanted to tell her about his health-kick but he felt silly.

‘Oh darling, I am so excited. I thought about you all last night at the club.’

Hargreave didn’t want to hear about the club. ‘I thought about you too.’

‘Did you really? I am very pleased. Okay, I must go to sleep now, I have to work tonight.’

Work. He did not want to think about it.

After he hung up he slumped back in the chair, and tried to make himself think about it. Lord, what am I doing, feeling like this about a …? Say it – a whore? Feeling possessive … romantic … smitten. Feeling … over the moon about her. Aren’t you making a bit of a fool of yourself? Don’t forget she’s a whore.

But I wouldn’t be the first man to get smitten by a whore. Whores can be fascinating. Exotic, romantic, even, you wouldn’t be the first man to fall in love with a whore.

Fall in love? What are you talking about, man? You’re not in love, you’re just in lust You’ve had a bit of a tough time with Liz, unloved, sex-starved, so it just feels like love, you just feel sorry for yourself. Whores are for fun, not love …

Okay, so have fun. Enjoy it, stop analysing it. Stop thinking about her ‘work’, and her ‘customers’, stop flinching about ‘discount’ and be grateful for it, grab every discount she gives you because this fun is going to cost you plenty if you keep it up. A three-month extension on her visa? How can you keep up with this for three months? And you won’t want to, you’ll burn the whole thing out soon and she’ll go back to Russia and you’ll be relieved. So be cavalier, just enjoy …

But cavaliers were fit, cavaliers could keep up with their lovers, they did not fall by the wayside just because they were forty-six. He felt tired when he got home from chambers, and he wanted a stiff whisky, but he made himself go out to jog again. But he only managed two kilometres before his heart and his knees told him to stop: the image of her nakedness could not beat the ache in his legs today. So, you gave yourself a workout at lunchtime, don’t overdo it. He walked back to his apartment block on Mansfield Road. He had one beer, one whisky, two boiled eggs, and went to bed. He was asleep before eight o’clock.

The next morning he could hardly stand. His knees were not swollen but they were giving him agony.

‘Cartilage inflammation,’ Ian Bradshaw said cheerfully on Wednesday. ‘From jogging – told you not to do it. Buy a bicycle, I said. Or an exercycle, one of those stationary things that executives use. And buy yourself a pair of proper running shoes – but don’t run, go for walks. Get the best, with springy soles. And for the next week that’s all you can wear on your feet.’

‘But I can’t wear running shoes to chambers.’

‘You’re the boss, aren’t you? Get a black pair, to go with your pinstripe suit, I’ll give you a medical certificate saying you’re a stretcher-case without them. Wear them to court, to cocktail parties, or you’ll have a cartilage removal operation – want that?’

‘No,’ Hargreave said sincerely.

‘Otherwise you’re in good shape,’ Ian said. ‘Heart fine. Got some colour again. Let’s look at my scar?’

Hargreave peeled back his shirt. Ian peered.

‘You’re healthy. Getting older, that’s all. I did a good job on that bullet, what’s left is pretty sexy. Tell the girls it was a jealous husband, makes them feel protective.’ He sat back. ‘What news of Liz?’

Hargreave pulled his shirt back on. ‘We’re getting divorced.’

Ian nodded. ‘Still in San Francisco?’

Hargreave buttoned his shirt. ‘I think so.’

‘No truth in the rumour she’s coming back to town?’

Jesus. ‘Who told you that?’

‘Yacht club. Don’t know the source.’

Hargreave’s heart sank. Just when he was going to have some fun. ‘I’ve just received her lawyer’s letter. If she’s coming back it’s just to pack the rest of her things.’

‘You can come and stay in my guest room while she does,’ Ian offered. ‘You don’t want any more scars. Did you marry under Californian law?’

‘Yes.’

Ian shook his head. ‘Same with me and Janet. Community of Property, half of everything you own. If Janet divorced me I’d be in trouble. Okay!’ He slapped Hargreave’s arm and stood up. ‘Just remember you’re forty-something, not thirty-something, come back for another vitamin B jab next week, and eat your wheaties. And whoever-she-is should have a smile all over her face. But no jogging. Buy an exercycle if you don’t want a bicycle.’