Читать книгу Zen Gardens and Temples of Kyoto - John Dougill - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеZen in Kyoto

Each year I receive around 5,000 visitors to my temple who want to learn about Zen. They come from many different nationalities and backgrounds, ranging from businessmen to travelers and university students. Many have misconceptions about Zen, but nearly all are interested in developing and practicing ‘mindfulness’ in their lives.

Over the centuries, the Zen world in Kyoto has developed a unique culture in terms of focussing attention. It is evident in such ‘Zen arts’ as the tea ceremony and Chinese ink work. Its influence can be seen also in architecture, garden design, Japanese archery and martial arts. We can, in fact, find this clear, concentrated attention reflected in all aspects of Zen culture.

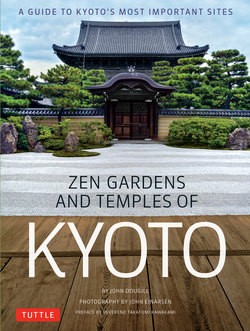

Luckily, we now have a book to guide us around the gardens and temples, revealing more than is immediately obvious. Between them, long-time residents of the city, John Dougill and John Einarsen, are able to bring the places to life. Author of an acclaimed cultural history of Kyoto, Dougill provides us with background information necessary to an understanding of the institutions. Award-winning John Einarsen’s pictures balance panoramic views with eye-catching details to recreate the serenity and beauty of the Zen atmosphere.

It gives me great pleasure to recommend this book. It will help me communicate the rich experience of Zen to others as well as be a worthy souvenir for anyone visiting the city. And for those who have yet to experience Kyoto and its Zen heritage, the book will surely be a great enticement.

—Reverend Takafumi Kawakami, Shunko-in Temple, Kyoto

Dry landscape gardens use raked gravel to represent water, with rocks representing islands or mountains. Some see this in abstract terms as the movement of the mind interrupted by thought. For onlookers the garden may serve as an aid to meditation, while for monks raking the gravel is an exercise in mindfulness.

A National Treasure:

Kyoto and the Art of Zen

Kyoto is a city blessed in so many ways. It is home to seventeen World Heritage Sites. It is the city of Noh theater, ikebana and the tea ceremony; of gardens, geisha and Genji; of crafts, kimono and weaving; of poets, artists and aesthetes; of tofu, saké and kaiseki delicacies. It is also a city of temples, shrines and museums and of festivals and seasonal delights. And on top of all that, it is a city of Zen—Rinzai Zen, to be precise. It was here that the fusion of Chinese Chan with Japanese culture took place, producing a sect that has become synonymous with satori, or ‘awakening’. Zen and Kyoto go together like love and Paris.

The genius of Japan, it is often said, is in the adoption and adaptation of foreign customs. Zen is a prime example. In the Heian period (794–1186), leading priests of Kyoto went on perilous trips to China to study at the feet of the great masters, the result being the introduction of new types of Buddhist thought. In 1202, a temple was set up in Kyoto which challenged the established order, for it preached that the sole means of salvation was through Zen meditation. The name of the temple was Kennin-ji, and though it remained nominally part of the Tendai sect, it proved a pioneer for the new teaching.

Zen soon found favor with the ruling classes, first with the warrior regime in Kamakura and then with the imperial court in Kyoto. By the Muromachi period (1333–1573), when the Ashikaga shoguns made Kyoto their capital, Zen’s place was assured and the whole arts and crafts of the age were affected as a result. A city once known for aristocratic indulgence embraced a new order that spoke to essentialism and the suppression of self. Just 200 years after Myoan Eisai (1141–1215) had single-handedly introduced Zen to the city, seven mighty monasteries encircled the imperial capital. Robed figures with shaved heads roamed the corridors of power, while inside the thick temple walls, guarded by sturdy gates, monks rose before daybreak to begin a daily round of chanting, meditation and pondering anecdotes about eccentric Chinese masters.

Zen temples have attractive wooden verandas which give onto gardens and provide a sense of oneness with nature, as here at Ikkyu-ji. In this way, the architecture fosters awareness of transience and the passing seasons.

The huge Sanmon gates of Zen temples are ceremonial in nature and feature altar rooms on the upper floor. Nanzen-ji is a noted example, the formidable size indicative of the temple’s elevated status.

Thanks to patronage from on high, the temples were able to acquire some exquisite decoration for their monks’ quarters. Because of a desire to strip away illusion, the artwork had a minimalist character which tended towards simplicity and tranquility. Gardens were laid out by the top designers of the age, gorgeous fusuma paintings were executed by leading artists, and magnificent statues were commissioned for the halls of worship, while on the ceiling of the lecture halls were painted astonishing pictures of swirling dragons.

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Buddhist temples in Japan have had to be self-financing. Income from visitors plays a vital role, and because of the attractiveness of Kyoto there can be formidable crowds of tourists at peak times. Some temples have embraced the opportunities this presents, while others are reluctant to compromise their religious purpose. Visitors looking for a moment of reflection during the periods of cherry blossom and maple viewing would be well advised to seek out a peaceful nook in one of the less famous temples. Those who are in earnest will rise at dawn to join the early morning zazen (sitting meditation) groups that welcome newcomers.

Sixty years ago, when temples were less frequented by tourists, Ruth Fuller Sasaki came to live at Daitoku-ji where she wrote of Kyoto in letters to the First Zen Institute of America. She had words of advice for her fellow countrymen, and though much has changed in the meantime her words remain apposite.

I assume those who come to Japan for only a few weeks and hope to find out something about Zen in that time will come to Kyoto, for only in the old capital can at least the outer expressions of Zen still be found in abundance. Here are seven of the great Rinzai Zen headquarter temples, each with its monastery. Here are the finest examples of Zen gardening. Here the old arts of Japan—Noh, tea ceremony, flower arrangement, sumi painting, calligraphy, pottery, among others—can best be enjoyed or studied…. There are a few rules you should lay down for yourself. The first is to put your camera away. Secondly, do not plan to do more than one major thing in one day. Thirdly, take your time and go leisurely…. When you return home and your friends ask you what you have learned about Zen in your three or four weeks’ stay in Kyoto, probably you will have to say “Not much.” Not much you can speak about, perhaps, but much you will never forget.

Since Fuller Sasaki’s time, Zen has spread around the world, and today there are hundreds of training centers outside of Japan. None, of course, have the patina of age or the cultural wealth accumulated by the temples of Kyoto. This was highlighted in an exhibition put on in 2016 at the Kyoto National Museum to celebrate the 1,150th anniversary of the death, in 866, of Rinzai (the Chan Chinese Linji Yixuan), who introduced the oldest school of Zen to Japan. Paintings, statues, calligraphy and ritual items spoke of a keen aesthetic sense shaped by the indigenous taste for naturalness and purity.

Here in Kyoto’s river basin, shielded by its protective hills, the Japanese sensibility has been nourished over long centuries. When the pursuit of beauty came into contact with the thinking of Zen, the result was an infusion of profundity and paradox, which gave rise to a remarkable aesthetic of minimalism. It is manifest in the awe-inspiring architecture, in gardens conducive to contemplation, in art that speaks of transcendence, and in calligraphy that is an art in itself. It marks one of mankind’s greatest accomplishments, and it is one that deserves wider celebration. How better than through the discerning eye of John Einarsen, long-time devotee of the city and inspiration behind the award-winning Kyoto Journal? In the lens of his camera is captured a very special cultural heritage—the spirit of Zen. The spirit of Kyoto Zen.

The lotus blossom is a symbol of enlightenment for the way its pure beauty emerges from muddy depths. The flowers bloom from mid-June to early August and are seen to best effect in the Lotus Pond at Tenryu-ji.

Carp are a symbol of perseverance because of their determination to swim upstream. By achieving their aim, they became associated with such positive attributes as courage, strength and good fortune.

Water basins signify the importance of spiritual as well as physical purification. They are typically found beside pathways leading to tea houses, where the sound of flowing water serves to soothe the minds of visitors.

From China to Kyoto:

The Story of Zen Buddhism

Zen first emerged as a Buddhist sect in Chinawhere it was known as Chan (meaning ‘meditation’). Indeed, Zen is said to have originated in the encounter between Indian Buddhism and Chinese Daoism. Like other Buddhist sects, it refers back to the life and teaching of the historical Buddha, whose actual name was Siddharta Gautama. Since he was a prince of the Shaka clan, in Japan he is known as Shakyamuni (‘sage of the Shaka’) or Shaka Nyorai (Nyorai being a term for the Enlightened). After long years of ascetic practice, he was meditating under a bodhi tree when he experienced a deep realization that all people have Buddha nature and are endowed with wisdom and virtue but that they fail to realize this through being deluded.

For the rest of his life, Shakyamuni taught a message of salvation through spiritual awakening. His doctrine was based on the Four Noble Truths: life is suffering; suffering derives from desire fueled by the ego; there is need to overcome the ego; the way to do so is through the Noble Eightfold Path. Different sects emphasize different aspects of the teaching, and for Zen ‘the flower sermon’ holds particular significance. When Shakyamuni held up a single flower in silence, only one of his disciples smiled with understanding. He was named Mahakashyapa and Shakyamuni picked him as his ‘Dharma heir’ (successor in teaching). The incident encapsulates the essence of ‘the wordless way’, namely that truth is intuitive. As the Greek author Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904) put it: “Zen represents human effort to reach through meditation zones of thought beyond the range of verbal expression.”

As time passed, Buddhism spread across Asia and there developed a distinctive Southern and Northern Tradition, which differed over how best to strive for enlightenment. It was from the Northern Tradition, emphasizing compassion for others, that emerged a legendary figure called Bodhidharma (Daruma in Japan). According to tradition, he was the 28th Patriarch, by which time Buddhism had become largely a matter of scholarship and good works. He is said to have sailed from India into China around 520, where he promoted the practice of meditation. Instead of seeking the truth in words and texts, he advocated looking within, as can be seen in a famous definition of Zen attributed to him:

A special transmission outside the scriptures;

Without dependence on words and symbols;

Directly pointing at the heart of man;

Seeing into one’s nature and the attaining of Buddhahood.

One of Zen’s most famous stories concerns a monk called Dazu Huike, who wanted to be a disciple of Bodhidharma. The legendary Zen founder showed little interest, however, famously sitting for years in front of a cave wall at Shaolin, so after repeated rejections Huike cut off his arm to prove his sincerity. The painting of Huike Offering His Arm to Bodhidharma was done by Sesshu Toyo in 1496.

The emphasis on experiential knowledge is a vital element of Zen, and Shakyamuni’s appointment of Mahakashyapa was the first in a teacher-disciple transmission of wisdom that has continued to the present day. In each case, the enlightenment of a disciple has to be verified by a master, and the lineage of such masters is a matter of importance in Zen.

Bodhidharma, or Daruma, remains a living presence in Zen temples, where pictures of him are often displayed. Many of these show him meditating in a cave, for tradition holds that he sat for nine years facing a cave wall in the mountains at Shaolin. Such was his determination not to fall asleep that he plucked out his own eyelids, as a result of which he is depicted with fierce features and bulging eyes. It is also said that he meditated so long that his legs and arms dropped off, which explains why Daruma dolls in Japan are shaped like a ball.

Transmission to Japan

As Chan Buddhism took hold in China, it was much influenced by Daoism, absorbing some of its thinking along with symbols and deities. Several favorite Zen anecdotes concern Daoist sages, and the often quoted “He who speaks does not know; he who knows does not speak” derives from Lao Tzu. By the ninth century, different Schools of Chan had appeared, amongst which was that of Linji Yixuan, known in Japan as Rinzai (d. 866). His school was characterized by the severity of its practices, which were rooted in zazen (sitting meditation) and the study of koan (Zen riddles). At its heart was a belief that the rational self was an illusion and not the final arbiter of truth.

Meanwhile, in Japan a meditation hall had been established in Nara as early as the seventh century, and later a form of zazen was introduced to the monks on Mt Hiei. However, these early transmissions did not develop into a separate teaching, and it is only with Myoan Eisai (1141–1215) that Zen is considered to have taken hold in Japan. At the time, religion in the imperial capital was dominated by the eclectic Tendai and the esoteric Shingon sects. With the onset of mappo in Japanese Buddhism in the eleventh century, thought to be a time of degeneracy in Buddhist practice, many people had turned to belief in salvation through Amida, who vowed to receive in his Pure Land all those who called on him.

The arrival of Zen in the early 1200s coincided with the coming to power of the samurai. A military government had been set up at Kamakura in 1187, which proved fortuitous for the new sect, as warriors and monks shared similar values—austerity, endurance, subjugation of self, fearlessness in the face of death. (Buddhists, however, both clerics and the laity, took a pledge not to kill.) The shogunate saw a political advantage in promoting Zen as a means of weakening other sects (Tendai, in particular, had an independent army of warrior-monks). The Hojo clan, the power behind the shogun, saw in the new Zen culture an alternative to that of the aristocracy. With the adoption of Zen in this way, it seemed that the Buddhist sects had all carved out a niche for themselves: “Tendai for the emperor, Shingon for the aristocracy, Zen for warriors, and the Pure Land sect for the masses,” was a popular saying.

The first temple to practice Zen in Kyoto was Kennin-ji, in 1202, but because of fierce pressure by the monks of Mt Hiei the monastery was forced to remain nominally part of Tendai. (It was only under the sixth abbot that it became fully Zen.) One of the early disciples at Kennin-ji, Eihei Dogen (1200–53), who had studied in China with a master from the Caodong School (J. Soto Zen), broke away to set up a temple in the south of Kyoto. The Tendai sect again acted to suppress a rival, prompting Dogen to leave the capital altogether after being offered land in what is present-day Fukui Prefecture, where in 1243 he founded Eihei-ji. It helps explain why Rinzai came to dominate Kyoto while Soto looked elsewhere.

The Gozan System

Major temples in China were often named after the mountain on which they were situated. In this way, ‘mountain’ came to be used as another word for temple. The Gozan system, literally ‘Five Mountains,’ referred to the official patronage of five major temples, and the Chinese model was taken up by the shogunate in Kamakura. In return for the donation of estates, the regime gained important rights, such as the power to appoint abbots, supervise standards and monitor financial affairs. The benefits to the temple thus came with a loss of independence.

The system started with five Kamakura temples (all Rinzai), and was then extended to Kyoto. In its final form, which was never rescinded, it consisted of five Kamakura temples and five Kyoto temples, with Nanzen-ji given supreme status above the two groupings. The Kyoto five comprised Tenryu-ji, Shokoku-ji, Kennin-ji, Tofuku-ji, and Manju-ji (now a subtemple of Tofuku-ji). Two notable exclusions were Daitoku-ji, which asked to be exempted to retain its independence, and Myoshin-ji, which chose to prioritize the practice of meditation.

In the Muromachi period (1333–1573), known as ‘the Golden Age of Zen’, the Ashikaga shoguns made Kyoto their capital and were powerful patrons of the Gozan temples. As a result, they became important centers of imported items and ideas, such as Neo-Confucianism. It inspired a period of creative vigor, exemplified by the Chinese ink paintings with their use of empty space. Gozan literature flourished, too, with an outpouring of poetry, treatises, diaries, commentaries and biographies, all written in Chinese. The new way of thinking—directly pointing at the heart of things—affected a range of art forms, from calligraphy and garden design to the tea ceremony, flower arrangement and Noh (whose creative genius, Zeami, was influenced by Soto Zen).

The arts of peacetime were halted by the destructiveness of the Onin War (1467–77), which devastated Kyoto and has been called one of the most futile wars ever fought. It started as a battle of succession to Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, founder of the Silver Pavilion, but with the passage of time the original cause was forgotten as rival armies stampeded across Kyoto. Fire raged throughout the city, and the mighty Zen complexes suffered along with everything else. As a result, most of the structures visible today date from rebuilding in the sixteenth century or later.

The civil war heralded a breakdown of central power, as Japan entered a period of Warring States when regional warlords vied with each other for power. Without the backing of a powerful shogun, the Gozan system fell into disarray, though ironically Zen as a whole prospered in the misfortune. The independent temples of Daitoku-ji and Myoshin-ji were boosted by donations from regional warlords for the establishment of subtemples. At the same time provincial rulers set up branch temples in their capitals. The top generals of the age received on the spot guidance from powerful Zen priests, who acted as negotiators or gave training in martial arts. Takuan Soho, briefly abbot of Daitoku-ji, is a famous example, drawing on Zen techniques to give much valued advice about swordsmanship.

Detail of one of the huge columns that support the Sanmon gate at Nanzen-ji. Hewn out of a zelkova in 1628, the column shows evidence of the passage of centuries.

The poet Hanshan and his friend Shide were a pair of eccentrics who lived near China’s Mt Tiantai. Known in Japan as Kanzan and Jittoku, they became a popular subject in Zen painting. Kanzan lived in a cave and is depicted with a scroll to indicate his poetry, while Jittoku was a foundling who worked in the temple kitchen and passed food to his friend.

The Edo Period and Modernization

With a return to stability under the Tokugawa shoguns, the country entered more settled times in the Edo Era (1600–1868). To counter the threat of Christianity, every family in the country was obliged to register with a Buddhist temple, and the terakoya system was introduced to promote public education by temple priests. With its Chinese roots Zen was well suited to promote the prevailing Neo-Confucianism. The connection was reinforced in 1654 by the arrival of a Chinese immigrant known in Japan as Ingen Ryuki (1592–1673), who not only introduced Obaku Zen but prompted an invigorating influx of Ming arts and crafts.

For Rinzai, the major development of these years was the work of Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1768), seen in hindsight as almost single-handedly reviving the moribund sect. He lived in a modest temple near the foot of Mt Fuji, turning down offers from Kyoto temples and devoting himself to the training of monks. He made a point of preaching to commoners and his drawing skills won him wide attention, particularly the idiosyncratic portraits of Daruma which he freely gave away. Such was his influence that it is said all contemporary Rinzai priests can trace their lineage back to him.

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the new government was eager to establish a state religion as in the West. They chose the indigenous religion of Shinto and imposed its separation from Buddhism, to which it had been conjoined for over a thousand years. As a pillar of the discredited Tokugawa, Buddhism found itself in disfavor and its funding was cut. With the loss of their estates, temples became financially insolvent and had to sell off valuable assets, including parts of their precincts. As a result, some of Kyoto’s Zen temples are barely a third or a quarter of their former size. Tenryu-ji is just one-tenth.

Buddhism was too deeply rooted to be eradicated, however, and it soon made a comeback. Priests became dependent to a large extent on funeral rites for their income. For many Japanese, the only encounter with Buddhism is through the death of a family member, when the elaborate obsequies involved in securing a safe passage into the afterworld can cost millions of yen. However, this too has come under threat in recent years as Japan’s population shrinks, particularly in rural areas. It is said that in the next couple of decades as many as a third of Japan’s 77,000 Buddhist temples are expected to close down.

To some extent, Zen in Kyoto has been shielded against the downward trend because of the tourist trade, which has seen a dramatic rise in numbers. Kyoto, a city of a million and a half, now attracts over 50 million visitors a year. For a religious sect that values silent contemplation, the revenue from tourists is a mixed blessing, as indicated by this notice posted publicly at Shokoku-ji: “Please respect the temple precincts, garden and environment as a religious space and keep all noise to a minimum. You will acquire Buddha’s providence from the bottom of our heart.”

Zen Spreads to the West

During the course of the twentieth century, as knowledge of Zen spread to the West, Kyoto played a prominent part. D. T. Suzuki (1870–1966) is a case in point. Born in Kanazawa, Suzuki studied Zen in Kamakura before working for eleven years in America. After returning to Japan and teaching English in Tokyo, he took up a professorship at Kyoto’s Otani University in 1921, where he continued teaching until the age of 89. He founded the influential Eastern Buddhist Society, and in 1927 published the first series of his ground-breaking Essays in BuddhismOther books followed, among them An Introduction to Zen Buddhism in 1934 and Zen and Japanese Culture in 1959. Over the years, Suzuki gave several lecture tours in the West, described as more like Buddhist sermons than academic talks. Although he has been hailed for his pioneering work, he has also proved a controversial figure who has come under criticism for espousing essentialism.

Among Western intellectuals to take an early interest in Zen were such notables as Satre, Heisenberg, Huxley, Jung and Heidegger. The Beat Generation of the 1950s looked East for inspiration, with Kerouac dubbing his book Dharma Bums (1958) and Gary Snyder coming to Kyoto to study Zen. (Other poets to have found inspiration in Kyoto include Kenneth Rexroth, Cid Corman and Edith Shiffert.) But perhaps the most influential figure of all was Ruth Fuller Sasaki (1892–1967), whose pioneering work played a vital role in opening up Zen to the West.

As Ruth Fuller, she had met Suzuki in 1930 while on a trip to Japan, and she returned to Kyoto the following year to do zazen meditation at a Nanzen-ji subtemple. As a wealthy widow following the death of her husband, she had continued her Zen practice in America, marrying the Japanese master Sokei Sasaki shortly before his death. In accordance with his wishes, she set up the First Zen Institute of America and traveled on its behalf to Kyoto in 1949. She was given use of a house in Daitoku-ji, and used her wealth to develop the site into the subtemple of Ryosen-an. Here she entertained such luminaries as Joseph Campbell, R. H. Blyth and her son-in-law Alan Watts. She was a formidable woman, at one time sitting zazen eighteen hours a day, and she dedicated herself to making Zen writings available to the English-speaking world. To that end, she created a research team, which included Gary Snyder, Burton Watson and Philip Yampolsky.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Zen experienced a cultish boom in the West fueled by books as disparate as The Way of Zen (1957) and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974). The spiritually displaced headed for ‘a golden triangle’ of Kathmandu, Kuta and Kyoto, and the streets of the city began to fill with seekers of satori (‘awakening’). Some returned home none the wiser, though others stayed on in the city to pursue their interest long term. Some even qualified as priests. Figures like ‘Shakuhachi Bob’ were prominent among the foreign community, and the appeal of studying Zen in the city was poetically caught by Pico Iyer in The Lady and the Monk (1991).

The diffusion to the West has been compared by commentators to the movement of Zen from China to Japan. Among the Kyoto priests facilitating the westward spread were Zenkei Shibayama at Nanzen-ji, a follower of D. T. Suzuki; the abbot of Tofuku-ji, Keido Fukushima, who was unusually open to teaching Western students; and Soko Morinaga, head of Hanazono University, who was the inspiration behind Daishu-in West in northern California and the Zen Centre in London. Through the work of such figures, Kyoto’s reputation as a citadel of Zen has been spread around the world. Eight hundred years after its establishment in the city, a religion based on sitting has proved remarkably mobile.

Incense serves as a purifying agent in Buddhism and is offered at times of worship. Since an incense stick burns on average for 30–40 minutes, it is used in Zen to measure the length of meditation sessions.

WAYS TO STILLNESS:

THE THREE SECTS OF ZEN

Contrary to the perceptions of many in the West, Zen is not the dominant strand of Buddhism in Japan. In terms of followers, the Pure Land and Nichiren faiths (if one includes the lay organization Soka Gakkai) are bigger, as is the esoteric Shingon sect. Moreover, within Zen there are three different schools: Rinzai, Soto and Obaku. Rinzai is the oldest, Soto the biggest, Obaku the smallest.

Of the 20,000 Zen temples in Japan, Soto has about 75 percent, yet in Kyoto it is Rinzai that is dominant. Indeed, of the 35 temples and subtemples included in this book, only three are Soto (Kosho-ji, Shisendo and Genko-an) while just two are Obaku (Manpuku-ji and Kanga-an). How is this explained? An old saying suggests the answer: “Rinzai for warriors, Soto for commoners.” While Rinzai appealed to the élite of Kyoto, Soto spread in the provinces with the support of regional lords. (Obaku was a latecomer.)

Of the three Zen sects, Rinzai and Obaku are the closest in thinking, for both trace their lineage back to the Chinese master Linji Yixuan (d. 866; Rinzai in Japanese). The difference can best be understood in terms of history. Rinzai arrived from Song China in the late twelfth century and subsequently became Japanized. Obaku arrived from Ming China in the mid-seventeenth century and retained many of its Chinese forms and regulations. The doctrinal differences are slight, however, and in recent times they have joined together in an association in which Obaku stands alongside Rinzai’s fourteen schools (which are mainly a matter of lineage).

The difference between Rinzai and Soto is more substantial. Rinzai sees meditation as a means to awakening, whereas Soto sees it as an end in itself. “Practice and enlightenment are one,” said Eihei Dogen, founder of the sect. For Soto, just sitting (shikantaza) is in itself transformative, and the striving of Rinzai is seen as counterproductive. In its attempt to trigger awakening, Rinzai makes more use of koan than Soto, which looks rather to intensity of meditation. Rinzai is known as the rough school, using a sudden sharp shock to jolt the sitter into enlightenment. Soto is known as the gentle school, taking a gradual approach.

Monks at Shokoku-ji emerge from the monastery’s kitchen, known as kuri. Over time, the quarters evolved to house temple offices and to function as an administrative center. The bell-shaped windows and doors that open outwards were features introduced from China.

In terms of the master–pupil relationship, the Rinzai master is said to be like a wise general ably directing his students, while the Soto master resembles a wise farmer, concerned with nourishing his plants. The difference in approach goes along with differences in practice: Rinzai does zazen facing the center of the room, Soto faces towards the wall. There is a distinction also in the length and manner of holding the kyousaku, the stick used for hitting sitters. As for walking meditation (kinhin), Rinzai prefers a brisk energetic manner with left hand wrapped round right wrist; Soto adopts a slow pace, with right hand wrapped round left. Such distinctions are of little significance, however, compared with the difference in emphasis, for while both aim at attaining a state of compassion, Rinzai is inclined to shout “Wake up!” whereas Soto urges “Just sit!”

Eat, Sit, Sleep:

The Daily Routine Of a Zen Monk

The seven great Zen temples of Kyoto each head a separate school of Rinzai Zen. These schools are administratively distinct but basically the same with regard to practice and teachings, and Zen priests are free to move from one school to another. Each school is headed by a chief abbot who is a qualified Zen master or venerable teacher (roshi). Assisting him in his duties are senior prelates, almost all of whom serve as priests at their own temples. Rinzai was originally a celibate tradition, but following the end of Japanese feudalism in 1868 the government authorized marriage for Buddhist monks as part of a program to weaken the religion. Although most of Kyoto’s great monastic abbots maintain the custom of celibacy, it is no longer obligatory.

To enter the Zen clergy it is first necessary to become the disciple of a temple priest. In the majority of cases, this means the son of a priest registering as a disciple of his father (Japan maintains the hereditary principle in several areas of traditional life). Laypeople are able to become disciples of a local priest or a priest with whom they practiced zazen sitting mediation. They will typically spend a year or two at the priest’s temple, then have an ordination ceremony qualifying them to enter a training monastery.

Entrance to the training monastery (known in Rinzai as sodo or senmon dojo) involves arriving at the entrance hall early in the morning and presenting the necessary documents from the ordaining priest. Applicants are refused entry for two days as a test of resolve. After waiting patiently for the two days, they are moved from the entrance hall to a small room where they must meditate for five days facing the wall. Only when this trial period is completed are they accepted into the monastic community.

A thick wooden block is struck like a gong to summon monks for functions. This one from Manpuku-ji has a Chinese inscription that reads “All who practice the way, pay attention! Birth and death are grave matters. Nothing is permanent; time passes quickly. Awake! Do not dawdle; devote yourself to your practice.”

Zen Training

The Zen sodo is basically a training hall. It is not, as in Christianity, a cloister in which to spend one’s life. Monks who wish to become temple priests are asked to train for at least three years. In this case, the sodo serves the function of a seminary. However, monks who are interested in a life of meditation remain at the monastery many years longer in order to advance as far as they can, which involves working on and passing koan (Zen riddles). In this case, they stay until they have completed the training process, something that can take from twelve to twenty years.

The few monks who finish the entire koan curriculum and are judged to have the qualities necessary to teach others receive a certificate of approval known as inka shomei, which qualifies them to become a Zen roshi. For such individuals it is common to undergo a period of post-monastic training, lasting several years, before they assume their teaching duties.

Just a few decades ago, Rinzai monasteries comprised communities of thirty or more monks, but nowadays, with the steep decline in the number of young people in Japan, most sodo manage with ten monks or fewer. The training consists of zazen, koan study, sutra chanting, physical labor (known as samu) and takuhatsu (begging for alms in nearby communities). However, zazen is central, for the meditative mind should be maintained even during all the other activities.

The formal practice of zazen occupies up to seven hours a day of the normal schedule. It is the basic technique by which practitioners seek to awaken to levels of mind deeper than discursive thought. By observing the mind’s workings, the practitioner comes to realize the illusory nature of the ego, which is basically no more than a construct of thought. This leads to a deeper understanding of the mind as something that is empty yet dynamic in nature. Ironically, in losing the sense of self, the meditator finds oneness with everything. Realization of this is called kensho (‘seeing one’s original nature’).

Koan are enigmatic problems that cannot be solved with the rational mind, such as, “What was your original face before you were born?” or “Does a dog have Buddha nature?” If used properly, they allow the practitioner to access a new mode of understanding beyond logical thought. In monastic practice, koan are assigned to students and their progress checked by the roshi during interviews. Once the master is satisfied with a student’s understanding, he assigns a different koan to deepen and refine the newly acquired insight. Traditionally, there are said to be 1,700 koan in all, though the number employed by any particular master varies considerably.

There are two main styles of zazen sitting meditation. That of the Rinzai and Obaku sects is done facing inwards towards the center of the room, whereas the Soto style is done facing the wall.

The Daily Routine

Apart from the formal practice of zazen, much of the monastic day is taken up with physical work, which is considered a vital means of cultivating mindfulness and distinguishes the Zen monastery from other Buddhist sects. Indeed, a Zen saying states that cleaning comes first, then religious practice, and thirdly study. By focusing on the job in hand, monks free the mind of needless distraction. Tasks include sweeping the grounds, cleaning, splitting firewood, cultivating vegetables and preparing food. As one wag put it, for people who sit around all day, there is a lot of hard work involved.

The monk’s life is carefully regulated, and first-timers are often startled by the military-style promptitude with which activities are carried out. This contrasts with the romantic image prevalent in the West. As Pico Iyer puts it in The Lady and the Monk “The Zen life is like a mountain wrapped in mist—though it looks beautiful from afar, once you start climbing there’s nothing but hard rock.”

The daily schedule differs between monasteries and there are variations according to season, but the basic routine is essentially the same. Early rising is followed by sutra chanting, zazen, cleaning and physical chores. Meals are carried out in silence. Takuhatsu mendicancy is conducted at least twelve mornings a month, while bathing is reserved for days with a four or nine in them (i.e. every five days). A typical day may run as follows, though it is not prescribed:

4 am Wake up

4.10–5 am Sutra chanting

5–7 am Zazen and interview with abbot

7 am Breakfast of rice gruel, salted plum and pickles

8–10.50 am Cleaning and work duties

11 am Lunch, typically barley rice, miso soup, cooked vegetable and pickled radish

1–3.50 pm Work duty

4 pm Light meal similar to lunch

5–8.30 pm Zazen and interview with abbot

9 pm Lights out

9–11 pm Night sitting

The monthly one-week intensive retreats called sesshin involve a greater focus on zazen and koan study. There may be twelve to fourteen hours of meditation (including night sitting) and up to four koan interviews a day. At a number of monasteries, laypeople are allowed to participate, living in the training hall where they are allotted a single tatami mat and a futon for sleeping. “Half a mat when awake [for zazen]; a whole mat when asleep” runs a Zen saying. For the duration of the sesshin, this small area represents the entire universe, channeling practitioners to look within. For some, the result may be a deep awakening.

Takuhatsu is the practice of begging for alms, whereby young monks in single file are led through neighborhoods intoning “Hooo ... hooo….” (meaning Dharma). Donating food and money is rewarded with sutra chanting, which brings spiritual merit. Here a young monk in outfit holds out his satchel-bag for offerings, bearing the words Tenryu Sodo (Tenryu monks’ quarters).

THROUGH FOREIGN EYES:

AN INTERVIEW WITH THOMAS YUHO KIRCHNER

Thomas Kirchner is a Rinzai monk and caretaker of Rinsen-ji, a temple which is part of the Tenryu-ji complex in Arashiyama. Born in Baltimore in 1949, Kirchner came to Japan in 1969 for a one-year course at Waseda University, following which he stayed on to pursue an interest in Zen. In 1974 he was ordained as a monk and given the name Shaku Yuho, spending time at Kencho-ji in Kamakura and later at Kennin-ji in Kyoto. He holds a master’s degree from Otani University (where D. T. Suzuki taught) and is a researcher at Hanazono University, the Rinzai Zen university. Amongst his publications are Entangling Vines, a collection of 272 koan; Dialogues in a Dream, a translation and biography of Muso Soseki; and an annotated translation of The Record of Linji, completing work left behind by Ruth Fuller Sasaki.

How did you first become interested in Zen?

As a young boy growing up in the 1960s, I read the books around at that time—D. T. Suzuki, Alan Watts, Philip Kapleau. Also Eugen Herrigel, whose book on archery led me to take it up in Japan. But it wasn’t just books, because during my first year at college I was deeply moved by Zenkei Shibayama, abbot of Nanzen-ji, whose talk I attended. He must have been in his seventies, but his bright, peaceful eyes and cheerful personality moved me deeply. Unlike some other Eastern sages I’d met, he didn’t seem to be selling anything.

What was the first practical step you took in pursuing Zen?

After studying at Waseda, I stayed on and wanted to try meditation. My archery teacher recommended a temple in Tokyo, which led me to want to explore Zen more fully. Through a contact there, I was introduced to a small temple in Nagano where there were only four people: the roshi, his wife, another practitioner and myself. Later I spent a few years as a lay monk at the monastery Shofuku-ji in Kobe. In 1974, after I was ordained as a monk, I spent four years at Kencho-ji in Kamakura and three years at Kennin-ji in Kyoto.

Monastic life is known for its hardships, so i wonder how you coped with that?

It’s something you get used to. The early mornings, the painful sitting, the cold in winter. It’s not easy at first as you have to retrain all your bad habits. But after a few years correct posture becomes natural and the pain recedes.

For a while you looked outside monastic life. As well as a master’s degree, you did an MEd, trained in acupuncture and shiatsu, and took a job as copyeditor at Nanzan University.

Yes, my parents wanted me to graduate (I had dropped out of college in America), so I came to Kyoto to study while teaching English and living in a tea house in Daitoku-ji. I wanted to see if there was something more to life.

But you went back to monastic life?

The reason was in the late 1990s I developed a tumor in my pancreas. My weight dropped from 70 kilos to below 50, and I was expected to die. But when it came to the operation and they cut me open, there was nothing but healthy tissue. The tumor had mysteriously disappeared. It was a life-changing event; as the old saying goes, “The proximity of death wonderfully clarifies the mind.” While thinking over my life, I found the most meaningful part was the time I spent in monasteries. Everything else seemed superficial, pleasant to be sure, but inconsequential.

How did you get such a prestigious position as looking after the temple where the famed Zen master Muso Soseki lived and is buried?

It was through people who knew me from my earlier spells in monasteries. If you live with people in a monastery for any length of time, you get to know them very well, like army buddies. It’s very intimate, and there’s a level of trust that you build up. So people who knew me asked if I would be interested in looking after the property (it had been empty for two years).

What do you have to do?

I maintain the grounds and rake the garden, which I think is the largest dry landscape in Kyoto, maybe even in the whole country. It takes a couple of hours a week. I also show visitors around, and I help out if there are foreigners on short courses at the monastery. It’s a life that suits me, as I enjoy physical work like growing organic vegetables and wheat.

What’s your impression of Zen in Kyoto?

Kyoto is the heart of Zen culture, so not surprisingly it tends to be conservative. There are centuries of tradition to maintain. Some people talk of a decline, but part of that is simply the falling population. Numbers are down in all walks of life. But there’s another factor, I think. Five hundred years ago there was a vitality about Zen because the level of suffering and the awareness of death was much more intense. Modern medicine shields us from that, and there’s so much distraction in modern life, such as the media and electronics. Religion is so far removed from daily life that some young people don’t even know what Zen is. But having said that, there’s a great spiritual thirst which materialism can’t satisfy. And there are still some truly inspiring roshi around. That gives me great hope for the future.

Whereas straw sandals are worn for takuhatsu alms begging (see opposite), wooden sandals known as geta are worn around the temple or on outings. These have white straps instead of the usual black in order to distinguish monks from laypersons.

Finding One’s Way:

The Design of a Zen Monastery

Kyoto has seven great Zen temple-monasteries, which dominate the city’s landscape. In order of foundation, these are Kennin-ji (1202), Tofuku-ji (1236), Nanzen-ji (1291), Daitoku-ji (1326), Tenryu-ji (1339), Myoshin-ji (1342) and Shokoku-ji (1382). Their design differs from the temples of earlier Buddhism and their architecture was a borrowing from Song China (960–1279). The layout correlates with that of the human body, so that the Buddha Hall lies at its heart and a straight spine runs through the main buildings. As in the Chinese tradition, the compound was aligned towards the south and comprises a set of seven structures. Apart from the Buddha Hall, there is a Sanmon (ceremonial gate); a Doctrine or Lecture Hall; a Meditation Hall; and a kitchen, latrine and bath. The name of each is displayed prominently on a wooden plaque below the eaves.

The main structures are Chinese in character, with buildings set directly on the ground and floors made of stone or tile. The woodwork is unpainted and the large wooden doors swing open rather than slide, Japanese-style. Zen is characterized by rigid and structured practice, and thus the cavernous halls give off an air of austerity in keeping with the life of the monks. The walkways between buildings are wide, suited to large processions, and though they may be decorated with trees, there are no ornamental gardens and the atmosphere is spartan.

Around this central Chinese core are subtemples in Japanese style, with tatami, asymmetry and residential architecture. They have a more intimate feel. Shoes are taken off and tatami rooms are separated by narrow corridors open to delightful gardens. These subtemples developed organically, by contrast with the symmetry and straight lines of the monastic buildings. The prime example is the Myoshin-ji complex, with 46 subtemples arranged like a medieval village centered around a church. The subtemples are privately owned, and although the head priest participates in monastic affairs, the building constitutes his family residence.

Some of the monasteries have lost their original layout or were conceived differently from the outset. Nanzen-ji, for instance, is aligned on an east–west axis, because it originated as a villa owned by a retired emperor. Others have been badly affected by disaster, particularly the Onin War (1467–77), which devastated the entire city. Indeed, the large temples have without exception all burned to the ground at least once. Some structures were never replaced, and others have been rebuilt several times over the course of their history. But while wood can be a liability in terms of fire, it can also be an advantage in terms of relocation, and several temples have benefitted from the gift of imperial palace buildings or magnificent castle gates.

Nearly every temple displays a large painted illustration of the grounds. Although fairly recent, these boards originated in an earlier tradition of keidaizu, prints of the compound common in the Edo period (1600–1868). This painted guide to Shokoku-ji shows its subsidiary temples of Kinkaku-ji and Ginkaku-ji in the top left and bottom right, respectively.

TEMPLE STRUCTURES

To fully appreciate the temple compounds, it should be borne in mind that when constructed the huge monastic buildings would have dominated the cityscape. Magnificent views over the capital were afforded from the upper floor of the large ceremonial gates. Sadly, in an age of modern high-rises, the wooden buildings have lost some of their former grandeur although the dimensions and woodwork are still awe-inspiring.

❶ Outer Gate (Somon) This is the general entrance, situated slightly off the central axis. It generally faces south in accordance with Chinese fengshui principles, with important buildings towards the north of the complex.

❷ Imperial Messenger’s Gate (Chokushimon) The ceremonial gate is reserved for the emperor and his envoys, signifying the importance of imperial patronage in the past. It stands on the monastery’s central axis and is normally kept shut.

❸ Hanchi This pond at the entrance to Zen temples, often square in shape and with an arched stone bridge, represents passing from profane into sacred space. The lotus is a symbol of enlightenment because of its ability to produce a pure and beautiful flower from muddy depths. The ponds also served as a source of water during the conflagrations to which temples were prone.

❹ Sanmon (Ceremonial Gate) Sanmon means ‘mountain gate’ (the word mountain is synonymous with temple). It is symbolic rather than functional, typically with an altar room on its second floor. It is also known as Enlightenment Gate since it represents the passage into the world of Zen. In some cases, the first of the Chinese characters is written as ‘three’ instead of ‘mountain’ to denote the three openings in the gate that represent ‘emptiness’, ‘no-mind’ and ‘no intention’. The space between the Sanmon and the next structure is planted with trees, which are used for rebuilding.

❺ Buddha Hall (Butsuden) Normally standing on the north–south axis between the Sanmon gate and the Lecture Hall, this houses the temple’s main object of worship. The building was the second largest after the Dharma Hall and its high ceiling and stone floor are thought to have enhanced the chanting of sutra. Most Kyoto monasteries no longer have one because the originals were not replaced after being burnt down (it was also felt that too much ritual distracted from Zen practice). Both Daitoku-ji and Myoshin-ji still have Buddha Halls.

❻ Dharma Hall/Lecture Hall (Hatto or Hodo) This formidable temple building, with its gleaming tiled roof and sweeping eaves, houses statues of deities, guardian figures and statues of former abbots and is also used for formal talks by the abbot. The columns supporting the roofs are made of sturdy zelkova (keyaki) wood. The slightly curved ‘mirror ceilings‘ bear magnificent paintings of dragons, thought to help guard against fire and evil spirits. Shielded beneath the dragons’ protection, the Dharma could be preached without fear.

❼ Meditation Hall (Zendo or Sodo) This hall plays a vital role in the monastery. Along the sides runs a raised platform on which monks sit in zazen meditation on zabuton cushions. The open space in the middle may be used for walking meditation. There is usually an image of Monju, bodhisattva of wisdom, whose vajra sword cuts through all delusion. The meditation space is combined with a training hall, where monks are allotted one tatami on which to live, with storage for bedding and shelving for a few possessions.

❽ Kitchen (Kuri) Traditionally, the kitchen is situated next to the Abbot’s Quarters. Many monasteries have vegetable gardens to cater for the vegetarian diet of the monks, with a typical meal comprising rice, miso soup, a vegetable side dish, pickles and green tea.

❾ Latrine (Tousu) The traditional toilet comprises a circular hole in the earthen floor. To cater for large numbers, neat rows of such holes were housed in a long wooden building. (The restored latrines at Tofuku-ji, oldest and largest of its type, catered for a hundred people at a time.) In the past, human excrement was a major source of income for the temples as it was used for manure and delivered to the estates of nobles and samurai warriors.

❿ Baths (Yokushitsu) The bath house used steam to conserve natural resources, since conventional baths would have consumed an inordinate amount of wood and water. There was a highly prescribed ritual for bathing, which was considered a form of spiritual practice. There are restored bath houses at Shokoku-ji, Myoshin-ji and Tofuku-ji. (In smaller institutions, the kitchen, latrine and baths were housed in a single building.)

⓫ Abbot’s Quarters (Hojo) The Japanese name Hojo translates as ‘Ten Foot Square Hut’, indicative of how small the original area was. Over time, as Zen was patronized by those in power, the Abbot’s Quarters became an important meeting place and grew in prestige. A covered walkway connected the building to the Lecture Hall (Hatto/Hodo), to which the abbot would proceed in his finery to deliver the important Dharma talk. Fusama sliding doors divided the area into six sections, with three south-facing rooms for entertaining dignitaries and three north-facing rooms for more private purposes. Generally speaking, the southern set contain a central altar flanked by sliding screens painted by famous artists, and the rooms look onto a courtyard covered with fine white gravel to provide a dignified air. The northern rooms typically have a living area, a study and a room for meeting acolytes. These look onto a more informal type of garden, sometimes used by the abbot for instructional purposes.

⓬ Bell Tower (Shoro) The monastery’s largest bell is rung at dawn and dusk each day. As at other temples, it is also struck 108 times for the New Year, each strike ringing out one of the attachments to which humans are prey.

⓭ Sutra Hall (Kyozo) A small building with shelving for storage of sutras and other documents. The sutras are scriptures passed down by tradition as the legacy of the historical Buddha. Originally, these were transmitted orally (in Pali) by his disciples, in particular Ananda. Different sects of Buddhism privilege certain sutra, and for Zen it is the Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyo).

⓮ Founder’s Hall (Kaisando) This is a hall for veneration of the founding figure of the monastery where special memorial services are held.

⓯ Subtemples (Tachu) Over the centuries, subtemples proliferated along the sides of the main temple axis. Many contain items of great value, such as paintings, dry landscape gardens and rustic tea houses. Most were funded by powerful patrons and staffed by monks who had retired from formal duties. Some were constructed by samurai who had converted to Zen and wanted to pursue a religious life.

⓰ Shinto Shrines (Jinja) The custom of paying respect to guardian deities (kami) was part of the Japanese tradition before the arrival of Zen, and continues today. In some cases, shrines were already in place before monasteries were built, and they were maintained for protective reasons. Other shrines were added later, even as recently as the late nineteenth century when Buddhism fell out of favor (and over 20,000 temples were destroyed). Temples sought to appease the authorities by establishing Shinto shrines to show compliance with the new state religion.

Visions of Serenity:

The Zen Garden

Japanese gardens have a long history, stretching back even before the pleasure gardens of Heian nobles (794–1186). These featured a pond around which were set villas and pavilions. Here aristocratic pursuits took place, such as fishing, moon-viewing, poetry writing and boating. Shorelines were replicated by rocks along the margin of a pond and waterfalls were reproduced by water emerging from between rocks. Some of the gardens were given a spiritual dimension by evocations of Amida’s western paradise, with its promise of salvation. By the eleventh century, the sophisticated gardening knowledge had been collected in Japan’s first book on the subject, Sakuteiki (Notes on Garden Construction).

Kyoto’s flourishing garden culture was facilitated by the city’s location in a river basin. In the forested surrounds were plentiful resources of wood and stone. Added to this was fresh-flowing water and underground springs. Moreover, the humid climate lends itself to the cultivation of moss, which grows easily on untended soil (Japan has only 0.25 percent of the Earth’s surface but is home to nearly 10 percent of known moss varieties).

With the introduction of Zen, a new of type of thinking permeated garden design. Rather than a place to enter, the garden became a place to view. As a consequence, most of the gardens in Zen temples are enclosed, as if to frame the scene and stop the mind from wandering. It is worth noting,however, that there is no such term as ‘Zen garden’ in Japanese. Rather, there are garden types that have been adapted to a Zen setting. Although they come in various forms, they share underlying characteristics to do with a lack of ostentation, an inclination to tranquility, a tendency for symbolism and an ‘elegant mystery’ (yugen). The Daoist connections are reflected in a sense of flow and the frequent reference to Chinese myth.

Bonsai originated in China and was adopted by the Japanese following the introduction of Zen. The tray here was a New Year’s gift to Taizo-in and features the ‘three friends of winter’—plum, pine and bamboo. Tending to temple gardens takes up to seven full days a month.

Rocks can be appreciated in their own right as aesthetic objects, though they may also be invested with symbolic significance. In the dry garden at Ryogin-an, laid out by Mirei Shigemori in 1964, they represent a dragon emerging from the sea and about to fly up to heaven (the mythical creature has the attributes of both fish and bird).

Japanese gardens often feature a set of three rocks, such as that above sited on a rise at Komyo-in. The grouping represents a Buddhist triad, whereby an enlightened being is flanked by two attendants. In Zen this denotes the Shaka triad, in which the historical Buddha, known in Japan as Shakyamuni, is accompanied by two bodhisattva, Fugen and Monju.

One of the earliest examples is the Sogenchi pond garden at Tenryu-ji. It was laid out by the founder, Muso Soseki (1275–1351), who in one of his writings warned against a worldly love of gardens. His intention was rather for the garden to serve a spiritual purpose, and the landscaped grounds draw in the surrounding hills to speak of oneness with nature. In this way, his creation is not simply an adornment but a lesson in Zen thinking.

The Dry Landscape

The type of garden most closely associated with Zen is the dry landscape (karesansui). At its most basic it simply consists of raked gravel or sand. The style originated in China, where it was found useful for areas lacking water, and it developed into a three-dimensional counterpart to Chinese ink painting. Its adoption in Kyoto stemmed from a number of factors, one of which was economic. With the collapse of the central government in the Warring States or Sengoku period in Japan (1467–1568), there were few powerful patrons to fund expensive gardens. The large pond gardens required a lot of land and labor. By contrast, the dry landscape only required a small area of pebbles and rocks. Moreover, maintenance was easy as a single monk could manage the raking and sweeping.

One of the most common features at Zen temples is the Horai garden, as here at Ryogen-in. Mythical Mt Horai constitutes one of a small group of islands where Daoist Immortals dwell, represented by the rock grouping in the corner. This is accompanied by two symbolic islands, that of the Turtle (in the circle of moss) and that of the Crane (vertical to signify the long neck). Together the creatures symbolize longevity and happiness.

The new style was particularly well suited to Kyoto because of the abundance of gravel brought into the city by rivers flowing down from the granite hillsides. It was favored by Zen because of its representational qualities. Raked gravel suggested open expanses of sea, or space, or eternity. The rocks spoke of moments in time, thoughts in the mind or islands in an ocean. The enigmatic nature of the compositions offered a visual counterpart to Zen riddles. “What is the meaning of the Buddha mind?” asks a well-known koan. “A single pine growing in a garden,” runs the answer.

A common form of dry landscape is the Horai Garden (Penglai in English). This refers to the ancient Chinese belief in the Isles of the Immortals, where people live happily free of the ills that plague ordinary humans. Dominating the four Isles is mythical Mt Horai, which is represented by a rock grouping out of which flows ‘the river of life’. In this ideal place is a symbolic meeting place of human and heavenly worlds, where opposites are brought together in harmonious coexistence, signifying the underlying oneness of things.

The unity of opposites is manifest in the form of Turtle and Crane Islands (the animals are Chinese emblems of longevity and good fortune). While the turtle can plunge to the depths, the crane can soar to the heights, so that in their coming together the world of division is symbolically transcended. Turtle and Crane Islands can be found in pond gardens as well as dry landscapes, with the crane represented by a vertical arrangement (as if about to take off) and the turtle by more horizontal features. In some cases, the islands are reduced to a simple yin–yang pairing of rocks, one vertical and one horizontal.

A TEA GARDEN

Another type of garden often found at Zen temples is that leading to a tea house. Rather than an object for viewing, the purpose here is to act as a passage between the mundane world of everyday life and the more serene world of the tea house. The Japanese term is roji, which means ‘dewy path’, and the materials are sober and subdued: moss, rocks, shrubs, bamboo, stone lantern and wash basin. They serve to calm the soul as the visitor prepares for the contemplative nature of the tea ceremony. “The garden serves the human soul,” writes Preston Houser. “It is a secular stage whereupon our spirituality is brought into play.”

The approach consists of a series of thresholds, and the effect is of entering deeper into nature. The route is determined by a path of stepping stones, set closely together for those wearing kimono. A sense of distance is conveyed by the winding course it follows, as if in keeping with the natural contours of the land. Near the tea house stands a water bowl for ablutions, symbolically purifying spirit as well as body. In this way, by removal of ‘the dust of the world’, the visitor enters into a different realm.

Kyoto boasts the finest collections of tea rooms in the world. Many are centuries old and made of fragile materials: bamboo, paper, earth. Some require special permission to enter or are only open to official groups. Several are off-limits to visitors altogether. Those that are available for inspection are often models of wabi-sabi, the aesthetic of rustic austerity. At the end of the garden path, it turns out, is a lesson in harmony with nature.

The tea garden is known in Japanese as roji, meaning ‘dewy path’ leading to the tea house. That of Koto-in provides a typical example, with a simple rustic gate separating the outer garden with its trees and bushes from the more sedate and sparse inner garden.

Sipping Zen:

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony as we know it today was initiated in Kyoto’s monasteries, and it came to fruition in the sixteenth century under a series of tea masters trained in Zen. Even though aristocrats had indulged in tea ceremonies in earlier times, it was mostly for pleasure and display. But with the introduction of Zen, the suppression of self came together with the pursuit of beauty, the result being one of the world’s great cultural practices. In this way the simple partaking of tea was imbued with a strong spiritual component, showcasing many of Japan’s finest traits: refinement, exactitude, attention to detail and an unerring aesthetic sense. In all of this, Zen played such a vital role that a traditional saying states that “Zen and tea have the same taste.”

It all began in 1191 when Myoan Eisai, founder of Kennin-ji, brought back tea seeds from China. Tea drinking had entered Japan in earlier times but had died out, and Eisai reintroduced the practice not only by passing on seeds for plantation but by promoting its life-enhancing qualities. He also advocated its use as an antidote to falling asleep during meditation. Accordingly, green tea became a feature of Zen life, with the preparation and consumption conducted according to Chinese practice. With the passage of time, the ritual was adapted to Japanese tastes, and amongst leading contributors were Zen priests such as Ikkyu Sojun and his disciple Murata Shuko, both with ties to Daitoku-ji (later dubbed ‘the head temple of tea’).

Murata Shuko was tea master to the aesthete-shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, for whom he built a four-and-a-half mat tea room at the Silver Pavilion. It became the prototype for later models. Shuko also introduced Zen calligraphy for decoration and favored a simple and natural pottery for his utensils, such as the Bizen style. These ideas were furthered by Takeno Joo (1502–55), a student of Zen from a Sakai merchant family who moved to Kyoto to study tea. Drawn to the aesthetic of wabi (rustic simplicity), he was inspired to build a tea room in the manner of the thatched huts used by farmers. Amongst those inspired by the teaching was Sen no Rikyu (1522–91), who codified the ceremony as we know it today. He was also closely connected with Daitoku-ji.

The tea served at Zen temples is matcha, made by whisking hot water and green tea powder. This is served in a bowl of aesthetic or historic significance, with particular attention paid to the color contrast with the tea. The somewhat bitter taste is offset by the sweetness of the accompanying confectionery.

Master of Masters

Rikyu was the son of a wealthy Sakai merchant and from an early age took an interest in the tea ceremony, studying for fifteen years under Takeno Joo. Like his teacher, he was drawn to the study of Zen at Daitoku-ji and he also traveled widely to visit first hand the places where utensils were made, such as the kilns for the pottery. By middle age he had acquired such a reputation that he was appointed tea master to Oda Nobunaga. It was an influential position, for tea was used as a diplomatic tool and alliances were cemented with gifts of expensive utensils. As tea master to the ruler, Rikyu was privy to matters of state.

One of Rikyu’s principles was that all should be equal in the tea room, so he dispensed with the niceties of rank and used a small ‘crawling entrance’ to prevent the wearing of swords and ensure humility in entering. He also promoted the values of wabi-sabi, an aesthetic that combines rustic simplicity with natural beauty and an awareness of transience. This was reflected in the utensils he favored, which were made of simple but natural materials. In a similar manner, his tea houses were built in the peasant hut style. His unerring aesthetic sense is captured in an anecdote about his gardener, who had swept the garden free of fallen leaves in keeping with the tea principle of cleanliness. Seeing this, Rikyu completed the scene by shaking a branch and scattering leaves over the path in an irregular manner as ordained by nature. The arrangement of autumn hues was a perfect wabi-sabi presentation for his guests.