Читать книгу The U.S. Naval Institute on Naval Innovation - John E. Jackson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

In his classic treatise on power, The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli succinctly defined the inherent difficulty in promoting change and innovation when he noted:

[T]here is nothing more difficult to carry out, nor more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to handle, than to initiate a new order of things. For the reformer has enemies in all those who profit by the old order and only lukewarm defenders in all those who would profit from the new order . . . (because of) the incredulity of mankind, who do not truly believe in anything new until they have had actual experience of it.1

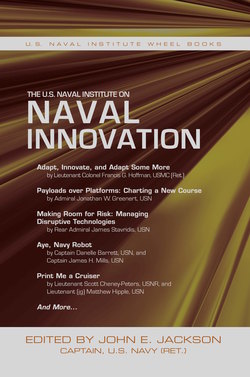

The purpose of this Wheel Book is to consider how the sea services have dealt with innovation and change in the past, as illustrated by selected articles that have appeared in the various periodicals and books published by the U.S. Naval Institute. It will also address the outlook for accommodating change in the future. If readers expect this to be a “cookbook” with a detailed and tried-and-true recipe for innovation, however, I acknowledge at the outset that no such recipe exists. The value derived from these pages will arise from the thoughtful consideration and assessment of ideas expressed by other maritime professionals in the first decade-and-a-half of the twenty-first century. (Other books in the USNI Wheel Book series will take a more historical approach, and will delve into USNI archives going back more than 140 years.)

At the most fundamental level, our topic relates to the only constant in life: change! Were it not for change, yesterday’s tactics and last year’s equipment would be adequate to provide for the common defense. But factors such as changes in political alliances, upheavals in cultural relations, and technological breakthroughs virtually guarantee that the path forward will be different from the path that brought us to the status quo.

I write these thoughts while serving on the faculty of the historic Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. It has been well documented that the College’s founding president, Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce, USN, embraced the changes he was witnessing in the Navy (and the world) when he founded the College more than 130 years ago. These changes were acknowledged in John Hattendorf’s centennial history of the College when he noted:

In 1884, the United States Navy was in a period of transition which reflected the broad developments in American intellectual perceptions, the growth of industrial power, technological progress, and general professional development. Change was in the air, and suggestions for future development were heard in many different areas.2

The issues facing today’s maritime leaders are, perhaps, not quite as transformational as those of Luce’s time, but I would argue that the rate of change is greater today than at any time in our history. As one tech-based example, the Apple iPhone first went on sale in 2007, and there have been seven updated replacement versions since then, an average of one per year. And in May of 2014, Apple sold its 500-millionth phone. Changes in other technologies, such as weapons systems or consumer electronics, and in culture—or even fashion—have moved at a similarly blistering pace. For this reason, I argue that this accelerated rate of change places a premium on adaptation and innovation in virtually every field.

Creative, innovative, and adaptive thinking is of particular importance today because of the highly fluid nature of world affairs. This period has been categorized by the acronym VUCA, a term developed at the U.S. Army War College in response to changes in the security environment over the last twenty years. The concept has garnered a wide following both inside and outside of government. The acronym represents the following characteristics of the modern world:

Volatility: the rate of change of the environment. Volatility in the Information Age means even the most current data may not provide an adequate context for decision-making. Beyond an ability to accurately assess the current environment, leaders must anticipate rapid change and do their best to predict what may happen within the time scope of a project, program, or operation. Volatility in the environment coupled with the extended timelines of modern acquisition programs creates a unique challenge for strategic leaders and their advisers.

Uncertainty: the inability to know everything about a situation and the difficulty of predicting the nature and effect of change (the nexus of uncertainty and volatility.) Uncertainty often delays decision-making processes and increases the likelihood of vastly divergent opinions about the future. It drives the need for intelligent risk management and hedging strategies.

Complexity: the difficulty of understanding the interactions between multiple parts or factors and of predicting the primary and subsequent effects of changing one or more factors in a highly interdependent system or even system of systems. Complexity differs from uncertainty; though it may be possible to predict immediate outcomes of single interactions within a broader web, the non-linear branches and sequels multiply so quickly and double back on previous connections so as to overwhelm most assessment processes. Complexity could be said to create uncertainty because of the sheer volume of possible interactions and outcomes.

Ambiguity: describes a specific type of uncertainty that results from differences in interpretation when contextual clues are insufficient to clarify meaning. Ironically, “ambiguous” is an ambiguous term, whose definition changes subtly depending on the context of its usage. For our purposes here, it refers to the difficulty of interpreting meaning when context is blurred by factors such as cultural blindness, cognitive bias, or limited perspective. At the strategic level, leaders can often legitimately interpret events in more than one way, and the likelihood of misinterpretation is high.3

How, then, can innovation, creativity, and adaptability help us deal with the VUCA world? Innovation often focuses on hardware: in the previous century, it was submarines and carrier-launched aircraft; today it is directed energy, drones, and other scientific breakthroughs. But in reality, innovation is about a great deal more than hardware. Leaders, both in and out of the military, must have adaptive and agile minds, able to operate efficiently in spite of this level of near chaos. Developing open minds, willing and able to consider new ideas, is facilitated by formal education programs such as those offered at the Naval War College and other professional military education institutions; through self-directed exposure to the thoughts of others by participating in programs such as the Chief of Naval Operations Professional Reading Program (CNO-PRP); and through involvement with the numerous interest groups and blogs that have proliferated on the internet. Professional competency in one’s chosen field is fundamental, but taking the next steps to expand your vision beyond your in-box is critical to becoming an innovator.

At this point, a few words about the nature of innovation are in order. As a baseline, it is interesting to note that a simple Google search on the term “innovation” delivers more than 127 million hits in less than a half-second! (The fact that you can access this level of information with a few keystrokes is itself remarkable evidence of innovation.) Much has been written on the subject, and one can find some consensus on the factors necessary to create an environment in which innovative and adaptive thinking can thrive. It has been suggested that in industry, government, academia, and in other fields, leaders should:

1. Stress the importance of creative thinking, and be open to new ideas.

2. Allocate time—“white-space” if you will—in busy schedules, to allow new ideas to arise.

3. Cross-fertilize: Encourage discussions between diverse individuals who may bring new insights based on their experiences. We should avoid talking only to people with similar backgrounds and training. We should seek to step outside of our comfort zone.

4. Tolerate mistakes and encourage mental “risk-taking.”

5. Reward creativity. Individuals with creative and adaptive minds are a valuable commodity and should be prized and protected.

6. Act on ideas. Great ideas and new concepts are only worthwhile if they result in action.

Hopefully these thoughts, consisting of just over one hundred words, provide some practical examples of steps we can take to foster innovation in whatever line of work we lead. The validity of these broad steps will be addressed in many of the articles reproduced in this Wheel Book.

Certainly, the process of encouraging innovation is not easy and there have always been impediments to change. Noted British military historian and theorist B. H. Liddell Hart is famously quoted as saying, “The only thing harder than getting a new idea into the military mind is to get an old one out.”4 I would argue that this sentiment applies equally to non-military minds, which are also conditioned by a lifetime of experiences to seek comfort in the familiar, and to remain cautious about the new and the unknown. Regardless of how difficult it may be, I argue that we must be innovative and adaptive if only because our enemies most certainly will be.

In addressing the subject of change, American historian and author Williamson Murray has noted:

It is clear that we live in an era of increasingly rapid technological change. The historical lesson is equally clear: U.S. military forces are going to have to place increasing emphasis on realistic innovation in peacetime and swift adaptation in combat. This will require leaders who understand war and its reality, as well as implications of technological change. Imagination and intellectual qualities will be as important as the specific technical details of war-making. The significant challenges here are how to inculcate those qualities widely in the officer corps and what are the peacetime metrics.5

Murray further stated:

It is all too easy to suggest that the American military needs to be more adaptive and imaginative in the twenty-first century. How to do so is the real question. Again, the answer is a simple matter, but its realization represents extraordinary difficulties because it involves changing military cultures that have evolved over the course of the past century. And cultural change in large organizations represents an effort akin to altering the course of an aircraft carrier.6

Innovation, from a military strategist’s perspective, is the single greatest guarantor of success. Inability to innovate—especially in the modern world—is a guarantor of failure. Returning once again to Murray:

A crucial piece of the puzzle for successful adaptation lies in the willingness of senior military leaders to reach out to civilian experts beyond their narrowly focused military bureaucracies. No matter how expert senior officers may be in technical matters, they can rarely, if ever, be masters of the technological side of the equation. Thus, real openness to civilian expertise in the area of science and technology must form a crucial portion of the process of adaptation.7

Similar factors drive successful innovation in peacetime as drive successful adaptation in war. Both involve imagination and a willingness to change; both involve imagination as to the possibilities and potential for change; and both demand organizational cultures that encourage the upward flow of ideas and perceptions, as well as direction from above. Particularly important is the need for senior leaders to encourage their staff and subordinates to seek out new paths. Both involve intellectual understanding as well as instinct and action.8

Much has been written over the years trying to explain and rationalize the nature of military innovation. Some suggest that innovation is more likely to occur in times of peace, when resources (R&D funding and research time) may be more plentiful. Others argue that innovation and adaptation are more likely to succeed during combat, when the stakes are higher and immediate results can be measured through changes on the battlefield. There is no “right answer.” In a similar manner, some researchers hold that innovation must come from a uniformed “maverick” able to push his ideas through unyielding bureaucracies and seniors in the chain-of-command, while others theorize that innovation must come from outside the armed services themselves, from civilian leaders in the executive and legislative branches of government. Again, there is no single “right answer” or clear path. Historical examples can be found to support each perspective, and some will be offered for consideration in the articles that follow.

Since the U.S. Naval Institute is, by design, the “Independent Forum of the Sea Services,” this Wheel Book has an appropriately saltwater flavor. In recognition of this fact, mention should be made of the fact that in 2012, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert, USN, in a desire to encourage creative thinking in the naval service, created the Chief of Naval Operations Rapid Innovation Cell (CRIC), which is hosted by the Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC). According to an 11 September 2013 NWDC press release, the purpose of the CRIC is

to provide junior leaders with an opportunity to identify and rapidly field emerging technologies that address the Navy’s most pressing challenges. The CRIC capitalizes on the unique perspective and familiarity that junior leaders possess regarding modern warfare, revolutionary ideas and disruptive technologies. Participation in the CRIC is a collateral duty that does not require a geographic relocation or release from one’s present duty assignments. Each member proposes a project and upon acceptance, shepherds their project to completion. The new members will rotate into the CRIC as current members complete their projects and rotate out. CRIC members regularly meet with leading innovators in the government and civilian sector, and have access to flag-level sponsorship, funding, and a support staff dedicated to turning a member’s vision into reality. Members generally commit about four days per month outside of their regular duties, participating in ideation events and managing their project. Because CRIC membership is project-based, length of membership depends on the duration of the individual’s project but should not exceed 24 months.

CRIC members are provided with modest funding to research, demonstrate, and promote ideas with the potential to have “outsize impact” on the future Navy. The CRIC and similar initiatives hold promise as methods to encourage innovation in the sea services. You can learn more about the CRIC at https://www.facebook.com/navycric.

The need for innovation and adaptation is evident in the Navy/Marine Corps/Coast Guard, and also throughout the Department of Defense. In mid-November 2014, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel announced the Defense Innovation Initiative as “a Department-wide initiative to pursue innovative ways to sustain and advance our military superiority for the 21st century and improve business operations throughout the Department.” The letter establishing the initiative is included, for ready reference, as the final exhibit in this Wheel Book. One of the first steps taken in launching the initiative was the establishment of the Defense Innovation Marketplace (http://www.defenseinnovationmarketplace.mil) as a clearinghouse and linking tool to connect industry, academia, the scientific and engineering communities, and the DoD workforce to one another for the purpose of exchanging ideas and concepts. While Pentagon initiatives often come and go, it is hoped that this “jump-start of innovative thinking” will result in significant improvements in the way America defends itself in the decades to come.

In the pages that follow this introduction you will find book chapters and articles addressing ways leaders can establish an environment where innovation has a chance to succeed; examples of adaptation successes and failures; and some creative ideas that could shape the Navy of the future. This Wheel Book is divided into four parts:

PART I: The Innovation Imperative, where we review some general thoughts about the impact that innovation and disruptive technology can have on operations in the maritime realm, and how change can be embraced and channeled for future success.

PART II: The Unmanned Revolution, in which we consider the impact that unmanned and robotic systems are having now and will likely have in greater measure in the near future. Many of these systems represent the types of disruptive technologies described by Harvard’s Clayton Christenson: “Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, smaller, simpler, and frequently, more convenient to use.”9 The first generation of military robotics has already demonstrated that they meet many of these characteristics.

PART III: CYBER, the Most Disruptive Technology, wherein various authors reflect on the all-encompassing threats and opportunities represented by modern society’s dependence on computer-controlled and cyber-linked networks.

PART IV: Thoughts on Possible Futures, where a few specific “outside-the-box” technologies are identified and briefly discussed.

The choice of the articles and chapters reproduced here was extremely difficult, and more than 180 articles published since the year 2000 were initially chosen for consideration. This volume of information speaks to the quality and breadth of discourse that takes place under Naval Institute auspices every year. While no anthology can be exhaustive on any given topic, we hope this compilation is comprehensive enough to engender thoughtful consideration of the subject and that it will spark the intellectual curiosity of the reader.

Change is in your future; how you deal with it is up to you!

Notes

1. Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince (New York: New American Library, 1952), 49–50.

2. John Hattendorf, Sailors and Scholars (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 1984), 8.

3. Strategic Leadership Primer, 3rd Edition (Carlisle, PA: United States Army War College, 2010), 11–12.

4. B. H. Liddell Hart, Thoughts on War (Gloucestershire, UK: Spellmount Publishers, LTD, 1944), 42.

5. Willliamson Murray, Military Adaptation in War (Alexandria, VA: Institute for Defense Analysis, Paper number P-4452, Chapter 8, 2009), 16.

6. Ibid., 26.

7. Ibid., 16.

8. Ibid., 4.

9. Clayton Christenson, The Innovator’s Dilemma (New York: Harper’s Business Review Press, 2013), xviii.