Читать книгу The Curse of the Ripe Tomato - John Eppel - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

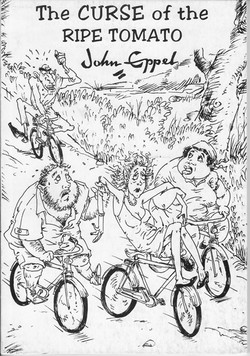

ОглавлениеChapter Three

Duiker has an Idea

Their long-term plan was to return home; their short-term plan was to give notice at the factory - a week was sufficient - and then go on a cycling tour of England and the flatter countries of Europe.

What about Fred Grommet Esquire? Nothando didn’t think he’d even notice her absence. In recent months he’d been getting his own beers from the fridge, and his own tins of Ambrosia rice pudding from the grocery cupboard. Baked beans on toast was too much of an effort for Fred; besides, it made him fart like a pony. Duiker suggested that they put a curse on the Englishman. Nothando wasn’t so sure. Curses had a habit of rebounding. They discussed the matter over a cup of tea and a Cape apple each - Granny Smiths - which Duiker had purchased, on his way to work, from a Pakistani vendor. They settled for a mild curse, one that would torment but not kill Mr Grommet.

The next time he passed the Pakistani vendor, Duiker bought two Cape apples - Golden Delicious - and an Israeli tomato. While they crunched their apples, the two collaborators stuck pins and splinters of chicken bone into the tomato and said, “We curse you, Fred Grommet.” Then Nothando took the tomato home and left it weeping onto Fred’s pillow. The curse took effect almost immediately. Fred’s television went on the blink, and with it, his whole purpose for existence. Beer without TV was nothing, Ambrosia rice pudding was nothing, life was nothing. He took himself upstairs to bed and there on his pillow was the spiked tomato. “I’ve been cursed,” he gasped. “Knotty!” he screamed, “is dis your doing?”

But Nothando wasn’t there to respond. She’d made off with the milk money and those worldly possessions of hers that could reasonably be lugged around England on a squeaking bicycle.

“It’s voodoo, dat’s what it is,” muttered Fred, “flaming bloody voodoo.” He threw the tomato out of the bedroom window and it landed on the hat of a diplomat from a non-aligned country who took the matter up with the Home Office, and Fred was in for the high jump! However he did manage to get in a few days bed rest before the men in trench coats came to question him.

The two adventurers rendezvoused on the road they both knew well, outside the Alperton factory, underneath the saggy baggy window of the security guard’s room. They leant their bikes against the factory wall and sat down on the narrow pavement to discuss strategy. It was a cool but sunny morning in April. The ringing of countless burglar alarms that had been activated by the wind, reminded them that it was a Sunday. They thought they were the only people in the vicinity until the tell-tale reek of frying kippers began to defenestrate above them. Mr Major was on duty in the guardroom.

They moved upwind of the kippers and discussed their holiday in earnest. Their pooled resources were meagre. They certainly wouldn’t be able to afford accommodation in hotels or guesthouses, or even camping sites too often. What they needed was a light, durable two-person tent, sleeping bags, a Gaz stove, cooking and eating utensils, a powerful torch, lashings of cheap alcohol, and some oil for Nothando’s bicycle. While they were in London - Nothando would be moving in with Duiker till the end of the month - Duiker must arrange visas for Holland and Germany (the flattish parts), since he was travelling on a Zimbabwean passport. Nothando had a British passport which required no visas. Presumably Britons are more trustworthy than Zimbabweans.

Duiker saw Mr Major’s face for the first and last time when the latter poked it out of the window and accused the two foreign looking geezers of loitering with intent. Whereupon Nothando accused Mr Major of fouling the atmosphere with intent. Mr Major’s pallor went from strongish milky tea to weak milky tea. He then accused Nothando, somewhat obscurely, of affirmative action. She called him a fool in IsiNdebele: "Isiphukuphuku": which delighted Duiker who capped it with "Indwangu" (baboon). The chums gathered their things, mounted their bicycles, and rode off to the diminishing sounds of Mr Major’s voice: "Bleedin’ foreigners...lowering the value of property...proud to be English...fought against ’itler...pay my taxes...Queen Elizabeth...kippers.”

Duiker led the way. Out of consideration for Nothando’s age, he decided to try a shorter route to Earl’s Court. According to his London map, if they took the fat blue road called Westway A40 (M), it would lead them directly to Holland Road, thus reducing the distance by two or three miles. Duiker was proud of his bright blue Raleigh Roadster with Sturmey Archer gears and built-in dynamo. He’d bought it new with money earned from the Buckingham Palace curios. Nothando rode an ancient Rudge with no gears and with clip-on, battery charged lights. It had belonged to Fred’s late father, Shirley, who had kept it, if not himself, rust-free.

The feeder road that took them on to the A40 was rather steep and they were both pretty breathless by the time they reached the motorway. They got off their bikes and pushed for a while. They were surprised by the density of the traffic which prevented them for many minutes from crossing over the road. Duiker reasoned that since they would eventually have to turn right, the sooner they got onto the right hand side of the road the better. It seemed to be windier at that elevation and Nothando was compelled to tighten the doek on her head. Duiker’s thinning grey hair flapped free.

They re-mounted, Duiker still in front, and pedaled off. A concrete parapet was all that separated the westward bound traffic from the eastward bound traffic. So, the two cyclists, on the extreme right (the fast lane) of the westward bound traffic, were also on the extreme right (the fast lane) of the eastward bound traffic. The sensation was terrific. Juggernauts roared past them in both directions.

The cyclists began to relax a little when the hooting, then the shouting, started. They waved and beamed at the truckers as they hurtled past. This was more like it. Maybe the pommies weren’t so hostile after all. Just listen to them honking and parping and calling greetings, frantically waving. Ah, the Commonwealth! At last a sense of belonging. Duiker was almost moved to tears by what he felt to be a "camaraderie" of the road.

They’d traversed about a mile of the motorway when it began to dawn on Nothando that the hoots and shouts of the motorists were not greetings but warnings, dire warnings. This became quite clear when one of the truckers - driving a Scania, she noted with brief nostalgia - actually slowed down, creating an instant bottleneck in the fast lane, and shook his fist at them, calling them “Bloody idiots”. Didn’t they know that this was a motorway, not a bloody cycle track. “Turn around! Get back!” Apparently Duiker didn’t get the message because he waved with gay abandon and, almost ecstatically, cried, “Yoo hoo! Camaraderie!”

Nothando called to him to stop but he could not hear her. Instead he went faster, hunching himself, backside adrift, over the handlebars, and pedaling with fury. After all, he WAS in the fast lane. Then she too went faster, in order to stop him, and although her Rudge wasn’t a 3-speed, it had 28 inch wheels against Duiker’s 26 inch wheels; so once it got going, it went! In a minute she had caught up with him. “Duiker!” she gasped, “stop!”

He slowed to a stop, put his right foot on the road to steady himself, and turned to her. His face was radiant. “What’s up, pardner? Do you need the loo?” They had to shout to be heard above the traffic.

“Duiker, we’ve got to turn back.”

“Turn back! Why?”

In answer she pointed to a hairy face sticking out of a pantechnicon in the fast lane of the eastbound carriageway. It was not a friendly looking face and it seemed to be swearing. Then she pointed to a fist being shaken from an articulated lorry that careered past them in their lane. “They aren’t greeting us, Berry, they are cursing us. We are not allowed to cycle on the motorway.”

Duiker’s face fell. “But how can we turn back, Nottie? It’s one-way. Unless we can get our bikes over this wall.”

The traffic continued to hoot, the drivers to curse. Duiker began to panic but Nothando kept calm. She wasn’t for nothing a descendant of Chaka the Great. “That would be impossible,” she shouted. “We must turn round and go back. Push our bikes.”

Turning round was easier said than done. The vehicles that hurtled past them were sometimes only a few inches away. The stink of hot rubber suddenly made Duiker feel nauseous. His face went doughy. “It’s the tomato,” he muttered.

“What?”

“The tomato.”

“Speak louder, Duiker; I can’t hear you.”

They leaned towards each other, traffic screaming by. “The curse we put on your husband. It’s rebounding on us.”

“Yes. We should have consulted um-thakathi (witch).”

“Get real, Nottie; where you going to find um-thakathi in London?”

Parp, parp! "Idiots!”

Toot, toot! "Fools!”

Honk, honk! "Get off the bloody motorway!”

“In London you can find anything except Blue Ribbon roller meal. Get real yourself, Berry!”

Thus, the perilous A40 which sweeps across England’s capital city, was the venue for their first quarrel, the first of many, initiated, they feared, by an Israeli tomato which was sold by a Pakistani to a Zimbabwean and "given" to an Englishman.

In the second of carbon monoxide-sickened space between one truck and another, Nothando and Duiker swung their bikes around and began to push them the mile or so back to the off-ramp. The truckers continued to hoot and shout at them, and it was no use trying to explain that they realised they were in the wrong, and they were getting off the motorway as humbly and as unobtrusively as they could. Duiker tried for a while. He shouted "Sorry! We didn’t mean to!” until he was hoarse. He made apologetic gestures with those parts of his body that were free to make apologetic gestures. His face was abject with apology. But it did nothing to assuage the righteous indignation of those men in blue vests, leaning out of cab windows, and shouting, swearing, hurling abuse.

Two exhausted but deeply relieved Zimbabweans finally got off the motorway and were proceeding along Duiker’s normal circuitous route to Earl’s Court. In Uxbridge Road, not far from Shepherd’s Bush Underground, they stopped for a rest and a cup of tea, still hot, from Duiker’s thermos flask. Before Holland Road becomes Warwick Road, they turned left into Kensington High Street. They went past the Commonwealth Institute on their left and then turned right into Earl’s Court Road where Duiker’s bed-sit was situated. He had already made arrangements with his landlady, Mrs Grub, to have another bed moved in for his friend, nudge nudge, wink wink. “Who are you trying to fool, Mr Berry? Friend indeed! I vosn’t born yesterday, vos I, Mr Berry? You foreigners are all the same. You come here from all corners of the vorld, all corners of the vorld, Mr Berry, and vot do you do? - please don’t interrupt me ven I’m speaking - vot do you do, Mr Berry? You bleed us dry. Bleed

us dry, you do. Take advantage of our National ’ealth, take our jobs, take the food from the mouths of our youngsters - I said PLEASE... don’t interrupt me ven I am speaking... and then, on top of it all, you behave like animals. Not that I have got anything against sex per se, Mr... er... Berry, but there is a limit, isn’t there? A limit, Mr Berry.”

“Yes, Mrs Grub. I’ve come to pay you for my friend’s accommodation. It’s just till the end of April.”

The sight of hard cash always brought Mrs Grub down from her moral high horse; she became almost kindly for a while. “Of course - thank you - not that I think of you in that vay, Mr Berry. You Rhodesians... the same as us really... your English aunt and all... such a pity about that Bishop Tutu - ”

“Mugabe.”

“That Bishop Mugabe. Stealing your land.”

“No, Mrs Grub, WE stole the land. The English settlers. We stole the land from the Africans.” Duiker wondered if he would have admitted as much before his reunification with Nothando who, incidentally, was waiting patiently outside the blue, four storey house, holding both bicycles. Earl’s Court Road, even on a Sunday, was teeming with people from almost every country on earth.

The cash in Mrs Grub’s hand and the thought of the Spanish sherry it would purchase, softened her response to: "ve’re all entitled to our own opinions, aren’t ve, Mr Berry. Leastways in England ve are. Free country, England. Not like your Rhodesia.”

“Zimbabwe. May I introduce you to my friend? She’s waiting outside.”

“Certainly. Mind you, I ’aven’t got all day to chin-vag vith ewery Tom, Dick, and ’arriet. Make it snappy, vill you, Mr Berry.”

“Of course.” He went outside to call Nothando. They carried their bikes in. Mrs Grub allowed her tenants to keep bicycles in their rooms as long as they carried them everywhere. She wasn’t going to have dirty tyre tracks on her carpets.

When she saw the elderly black lady with a white doek on her head and off-white tackies (the English called them sand shoes) on her feet, she took a step backwards, said "Gawd alive!” and shut herself into her apartment.

“Come along, Ma Sibanda,” said Duiker putting his free hand on Nothando’s shoulder, “I’m going to cook you a meal to remember. What do you say to eggs, bacon, tomato, and toast?”

“Go easy on the tomato, Umqobompunzi.”