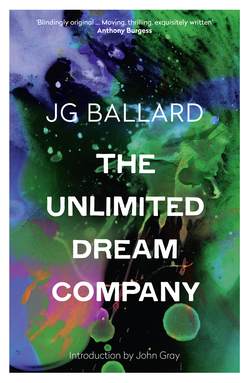

Читать книгу The Unlimited Dream Company - Джон Грей, John Gray - Страница 6

Introduction

Оглавлениеby John Gray

To anyone who thinks of J. G. Ballard as a dystopian writer obsessed by images of catastrophe this book will come as a surprise. One of his least-known novels, it is also one of the most powerfully lyrical. Ballard’s stories depict disaster zones: London drowned by the effects of climate change, an ultra-modern high-rise in which human beings struggle to survive, an American continent covered by desert and rainforest that a ragged band of explorers must cross. Yet the central thrust of his work is that disaster is not always an entirely negative experience. A seemingly destructive alteration in the outer world – geophysical or socio-political – may be the trigger for a process of psychological breakthrough. Instead of being destroyed, Ballard’s characters are liberated by catastrophe. Far from being a type of dystopian prophecy – though at times it is that too – his work has at its core an experience of inner transformation and renewal.

The Unlimited Dream Company is a succession of images held together by a single landscape, a succession more brilliant and more hallucinatory than anything else in Ballard’s fiction. Surrealist painting is a pervasive influence in his work – more influential than that of any writer, he used to say – and he followed the Surrealists in believing that the world could be remade by the human mind. The exotic landscapes he conjures are often as important as the characters who inhabit them. Where this book differs from his other novels is in its strongly poetic quality. With its short chapters, some only a page or two long, it reads at times like modernist verse. Only Hello America (1981), where he pictures New York swathed in golden sand-dunes and Las Vegas as the jungle capital of an almost deserted country, is similar in style. But whereas Hello America is full of deadpan humour, the mood that pervades The Unlimited Dream Company is joyful and rhapsodic.

Serendipitously, the actual Shepperton became for a time something like one of Ballard’s disaster areas in the floods that hit the town at the start of 2014. The Shepperton that appears in these pages is that same Thames suburb – where Ballard lived from 1960 until his death in 2009 – more magically transmuted. Hosts of brightly plumed birds – ‘flamingos and frigate-birds, falcons and deep-water albatross’ – have flocked into the town, and when the narrator leans against a pillar-box, trying to straighten his flying suit, an eagle ‘guarding these never-to-be-collected letters snaps at my hands, as if she has forgotten who I am and is curious to inspect this solitary pilot who has casually stepped off the wind into these deserted streets’. When the pilot leaves town, he looks up at ‘the vivid tropical vegetation that forms Shepperton’s unique skyline. Orchids and horse-tail ferns crowd the roofs of the supermarket and filling station, saw-leaved palmettos flourish in the windows of the hardware store and the television rental office, mango trees and magnolia overrun the once sober gardens, transforming this quiet suburban town where I crash-landed only a week ago into some corner of a forgotten Amazon city.’

It is no accident that the narrator’s name is Blake. In a letter, the poet William Blake declared ‘to the eyes of the Man of Imagination, Nature is Imagination itself’. Everything that Ballard’s character sees is seen through the eyes of the imagination. It is left open whether anything like the transformed Shepperton he describes exists or is no more than Blake’s delusion. He may even be dead and dreaming the place into existence. Impulsive, shifty and at times apparently psychopathic, Blake cannot be expected to give any remotely reliable account of himself. ‘Rejected would-be mercenary pilot, failed Jesuit novice, unpublished writer of pornography … yet for all these failures I had a tenacious faith in myself, a messiah as yet without a message who would one day assemble a unique identity out of this defective jigsaw.’

From what he tells us of the course of his life before he crash-landed, Blake is an archetypal loser. But he is also – whether only in his mind or in some alternate reality – capable of refashioning the world around him. He comes to Shepperton as a Surrealist saviour, seeding the town with his own semen, absorbing the population into his body in an act of magical cannibalism and exhaling them back into the town – now a seething jungle – as creatures that can soar with the wind. This suburban deity longs to awaken the town’s inhabitants from their earthly slumbers: ‘The unseen powers who had saved me from the aircraft had in turn charged me to save these men and women from their lives in this small town and the limits imposed on their spirits by their minds and bodies.’ Extending the Surrealist faith in the power of the imagination into something like mysticism, Blake affirms that what is created by the mind can be more alive than the deadly actuality: ‘My dreams of flying as a bird among birds, of swimming as a fish among fish, were not dreams but the reality of which this house, this small town and its inhabitants were themselves the consequential dream.’

The Unlimited Dream Company has all the marks of being the musing of a solitary mind, but the reverie contains some memorable portraits of other human beings. Tending him after he crashes into the town, the young doctor Miriam St Cloud becomes Blake’s bride. Tough-minded and initially sceptical, she finds herself accepting that he has come back from the dead. The Reverend Wingate also comes to accept Blake’s messianic role, and hands over the local church to him. Then there is Stark, the owner of a rundown zoo, who becomes a disciple of Blake’s, then turns against him and kills him, only for Blake to rise – again? – from the dead.

An intriguing feature of the book is the constant presence of birds. In Hitchcock’s film birds are enemies of humankind, but for Blake they are his kin. Flitting around the edges of the human world and soaring above it, they evoke the freedom of spirit that comes when the normal sense of selfhood, with its anxieties and repressions, is forgotten and left behind. The companionship of birds features in a short story teasingly entitled ‘The autobiography of J. G. B.’, which appeared in the New Yorker a few weeks after Ballard died in April 2009 but was published originally in French in 1981 and then twice reprinted in an English version in British science-fiction magazines.

The story describes the protagonist ‘B’ waking up to find Shepperton devoid of human beings. Driving to London he finds the city equally deserted, with not even a cat or dog in the streets. It is only when he reaches London Zoo that he finds sentient life – birds trapped in their cages, which seem ‘delighted to see him’ but fly off as soon as he frees them. The story ends with B making his way back to Shepperton where he settles contentedly into his new life, quickly forgetting his former human neighbours. His only visitors are the birds, and soon Shepperton turns into ‘an extraordinary aviary’. The closing sentence of the story reads: ‘Thus the year ended peacefully, and B was ready to begin his true work.’

As anyone who knew him can confirm, Ballard was a warm and convivial man who enjoyed deep and enduring human relationships. Though he presented himself to the press as reclusive, this was mostly a performance. But a part of him prized solitude. He resisted the idea that social interaction is always the most important part of life, and this impulse found expression in his work.

In welcoming the dissolution of his socially conditioned personality, Blake is like many of Ballard’s protagonists. The Unlimited Dream Company was published in 1979, but in what he regarded as his first novel, The Drowned World, the central character pursued a similar quest. Working his way into the sweltering depths of the jungle that has covered Britain, he leaves a final message he knows no one will ever read: ‘Have rested and am moving south. All is well.’ A few days later, he is ‘completely lost, following the lagoons southward through the increasing rain and heat, attacked by alligators and giant bats, a second Adam searching for the forgotten paradises of the reborn sun’.

In the course of his life Ballard creatively deployed a remarkably wide range of different styles and genres, but nearly all of his novels and most of his short stories seem to me to explore a single theme. Whether the subject is an apocalyptic shift in the environment as in The Drowned World (1962) and The Drought (1964), mental breakdown and transgressive sex in The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) and Crash (1973), urban collapse in Concrete Island (1974) and High-Rise (1975), the therapeutic functions of crime in Cocaine Nights (1996) and Super-Cannes (2000) or the black comedy of Millennium People (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), Ballard is showing how the personal identity we construct for ourselves is a makeshift, which comes apart when the stability of society can no longer be taken for granted. Empire of the Sun (1984) – the autobiographical novel that Spielberg brought to a wider audience – explores the same theme: it is in extreme situations where our habit-formed identities break down that we learn what it really means to be human. A drastic shift in the familiar scene may be the entry-point to a world that is closer to our true nature.

The paradox that is pursued throughout Ballard’s work is that the surreal worlds created by the unrestrained human imagination may be more real than everyday human life. According to William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.’ The dishevelled pilot who appears at the start of this book wants to escape the cavern completely. Blake’s Shepperton is the world as it could be if the doors of perception were ripped from their hinges. The world Blake sees is shaped by unfettered human desire, a creation of the imagination in which the imperatives of society and morality count for nothing.

For Ballard himself these surreal landscapes may have had a healing function. His traumatic childhood left him with the conviction – fully corroborated by events in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – that order in society has no more substance or solidity than a rackety stage set. Together with the scenes of cruelty he witnessed after he left the camp where he had been interned with his parents, the spectacle of desolation in the empty city of Shanghai must have left deep scars.

Ballard spent twenty years forgetting what he had seen during his childhood years, he said more than once, and another twenty remembering. His fiction was a product of this process, an inner alchemy that turned the dross of senseless suffering into something beautiful and life-affirming. Nowhere is the result more compelling than in The Unlimited Dream Company.

London, 2014