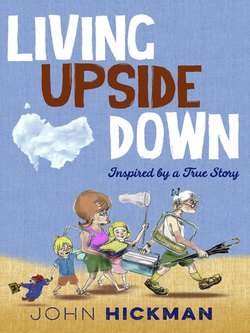

Читать книгу Living Upside Down - John Hickman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеTHE TREE OF KNOWLEDGE

As part of the application process, Sue and Roger are assigned to see separate doctors to avoid any risk of collusion.

“Heaven only knows why? What on earth concerns them? Collusion about what?”

“Don’t worry, Sue. Remember we’re dealing with a government department, and to boot one with an unlimited budget.”

“We should be thankful, that Fred is not booked in to see the vet.”

“Agreed. Then we’d probably see some real paperwork!”

As Jayne and James are not considered health risks by the Australian government, they tag along with Mum.

Roger’s doctor studies the forms in silence.

“I’ve had no prior experience with these Australian forms but I’ll complete them stage by stage as instructed. I see they require crosses and not ticks, most unusual. Go behind that curtain to fully undress, please.”

The doctor follows him and draws the curtains tight, so tight not even a microscopic particle of light penetrates through. Well and truly encased in a cocoon of gloomy solitude, he undresses quickly and then regrets it as the bone wrenching cold permeates every pore of his exposed skin. “This is why I’m doing this,” he mutters miserably to himself, “to avoid this bastard cold.”

He piles his clothes together and as he is about to leave his cold haven turned torture chamber, he realises he is still wearing his socks. Fully undress, please…resonates in his brain. Hopping from one foot to the other he removes the burdensome items and with a theatrical sigh attempts to exit but has difficulty finding where the curtains meet. For a few stalled seconds, which seem an eternity he looks as if he is trying to battle his way through an impenetrable wall of nylon.

After the doctor rescues him and guides him back into the room, Roger quips, “If that was the intelligence test, Doctor, I fear I failed.”

The GP allows a thin smile, “Please stand with your feet shoulder width apart, looking straight ahead.”

His hand cupped under Roger’s shrunken testicles, he instructs him to cough. “Does that hurt?”

“Only if I try to squeeze toothpaste at the same time,” Roger jokes.

Unfazed by Roger’s humour, he frowns darkly and asks, “Do you exercise?”

“Only when I have to,” Roger replies, and then with a leer, “although, I do try to get about twenty push-ups in at least three times a week.”

“Any exercise that doesn’t involve a coronary is good.” He writes, ‘Active’. More study and careful thought slows the process as he further studies the forms.

“How much alcohol do you drink?”

“Too much.”

The doctor frowns. He writes, ‘two beers a week’.

“I don’t like the way these government forms are framed but the road to hell is paved with good intentions, or so they say.” He pauses. “I suppose if you insist on going to Australia I can’t see anything medical to prevent you.”

He takes Roger’s blood pressure and checks his pulse with his wristwatch, then motions to Roger’s clothes indicating he can now return to the English modesty that is world renowned.

“That’s great, Doctor,” Roger crows struggling to get back into his clothes. His body it seems is used to the chill now and slow moving. He feels as if he is wallowing in Treacle.

Finally back in familiar territory Roger stands in front of the GP, about to leave, when his judge continues with a quote from the Bible, “You’ll probably get your three score plus ten the same there as here.”

“One thing though, do you need those?” The doctor is pointing to Roger’s packet of Chesterfield cigarettes in his top shirt pocket. Thinking he is short on words and asking for a smoke, Roger offers him one.

“No, no, I don’t want one!” He insists, waving his arms in the air in horror. “What I meant was can you? Would you? Stop smoking them?”

The doctor pauses, as if searching for the correct comment.

“If anything I can say to you here today,” he begins, “that might extend your life, it’s giving up smoking those damned, awful cigarettes.”

“Are you serious, Doctor?”

The GP nods enthusiastically. “Every cigarette you don’t smoke is definitely doing you good.”

“I’ve heard smoking may not be the best of pastimes health wise, but nothing has ever been stated officially other than it being a nicotine habit. My Gramps refers to them as coffin nails but in a joking way.”

The doctor enforces with a philosophical nod, “You really would be better off without them.”

Whilst smoking maybe harmful to his health, Roger is unsure if he wants to stop sucking down those magic bullets. On impulse he takes the opened packet out of his pocket and hands them to him, “Best throw them in your waste bin then, please.”

“Are you sure?”

Roger thinks that strange. “Yes, I’m sure.”

“Might you prefer to give up smoking after you’ve finished this packet?” The doctor asks.

Roger’s mouth erupts into a smile before he can reel it in. “You’ve never been involved in sales, have you, Doctor?”

The GP shakes his head. “No, I went straight to medicine.”

“Well,” Roger grins, “you’d closed the sale. No need to reopen it.”

At home, they compare visits. Sue’s was walk in walk out. Her Quack took one look at her and the two children, and signed the forms.

Sue is chuckling and pointing at Roger’s incorrectly buttoned shirt. “You have Tuesday’s button in Wednesday’s hole.”

“Sue,” Roger pauses, “On the Quacks advice I’ve given up smoking.” His Cheshire cat smile is as wide as though he has been conferred a junior spelling bee award.

That news almost receives a standing ovation by Sue. Within minutes every ashtray in the house is washed, dried, and disappeared as if by sleight of hand.

Roger turns his attention to Jayne. “What day is it?”

“Today,” Jayne replies, “Daddy not smoking anymore.”

“Bright girl.” Roger turns to Sue, “Our three year old daughter with the seven year old brain scores again.” He reaches out and grasps a wriggling, giggling Jayne for a big cuddle. “Turns out to be Daddy’s favourite day, Sweetheart, because it’s also your third birthday.”

Sue grins, “Time to celebrate with a cocktail cherry on a stick.”

Jayne has cordial and cake while Sue and Roger share a bottle of cheap calamity. Jayne wants their wine. Sue dips her finger in her own glass and puts it to Jayne’s mouth.

Sue whispers to her, “Drinking wine is like angels peeing on your tongue.”

“She appears to like angel’s pee,” Roger smiles warmly, “welcome to the family, Sweetheart.”

Sue becomes heuristic, “Remember wine is made from grapes, and grapes are fruit, and fruit is good for us,” then with a frown, “do you think we have a problem with alcohol?”

“Absolutely,” Roger replies, “as self-appointed sommelier I can confirm we don’t have enough of it. I’m also craving a cigarette as much as Fred devours his treats. Maybe it’s more of a habit than I realised?”

Sue is supportive. “I’m sure the cravings will grow less frequent for you.”

“I’ve got a plan to beat it, Sue”

“Oh, Roger that’s wonderful, what plan?”

“I haven’t got a plan really, but at work they love it when I say I’ve got a plan.”

Roger’s only difficult time is at work, when other people are smoking and offer him one, otherwise, Sue is proven correct. Roger finds if he inhales stale smoke from butts in an ashtray, any ashtray, it kills the moment.

“Admittedly carrying a full ashtray around with me would be an excellent plan, Sue.”

“It will make you look a complete Knucklehead, that or close to wearing a wrap-around, tie-at-the-back, white jacket.”

Soon he is turned off by the mere thought of sniffing an ashtray.

In the meantime, more forms, and choices to make, arrive from Australia House.

“All this would have confused Einstein,” Roger ploughs on as he grumbles.

“Melbourne appears to do what she does best,” Roger is thumbing through their statistics.

“What’s that?”

“I quote: ‘Often provides wet and cold days’. They admit to ‘changeable as in four seasons in any one day.’”

Sue has an involuntary little shudder. “What about Adelaide?”

“It’s a pretty city, well laid out, but cold enough in July for snow.”

Sue looks at Roger with a raised eyebrow. “Right, not Melbourne or Adelaide, got it.”

“They’re not interested in Fred, but it’s up to us if we want to pay for him.”

“Oh, Roger. Can we take him?”

“Don’t see why not, but it looks extremely expensive, Sue. Can we afford it?”

“No we can’t, can we?”

“No. Sorry. It’s too expensive.”

Pushing unpalatable thoughts about Fred to the back of their minds, they press on regardless with due consideration about fuck-all but climate. They draw a beeline northwards on their only map and lo and behold find the very place that initially appealed to Roger.

“Perth!” They say in unison.

“Okay. Let’s avoid anywhere further south.”

“Agreed. It’s too cold. Can anyone wearing thermal underwear be happy at all times?”

“That’s one decision down, Sue. Now they only want us to choose mode of travel. Ship or plane?”

“Maybe we should get ourselves some brave or stupid pills?”

To try to relax, Roger switches on some soothing music; — Chopin is one of his favourites. They continue to contemplate. He prepares to make inroads on a bottle of Chateau cut-price red wine, which starts going down rough. Very rough! Like a rough diamond that has lost its sparkle they are about to slide into it like a ferret down a drainpipe.

“I know that tomorrow morning my head will hate me,” he is offering another glass to Sue with a grimace.

Sue sips her wine slowly. “If it comes down to twenty-four hours of misery in the air or throwing up on a ship for six weeks, at least on the boat we’d get fresh air.”

Roger sets his wine glass down in front of him, and gazes into it as if glimpsing an uncertain future.

That night in his dreams, he is still searching for his elusive Seal Flipper Pie, interrupted by female seals skipping across vast empty grey oceans in a chorus line carrying freshly made whale pies.

After scraping three glaciers from his car windscreen, he is unable to stand upright. Then in semi-foetal positions, they take turns at clutching the cold ceramic curves of the only toilet bowl shared with many on an 1850’s sailing ship. Retching and arching like sick cats amid the wild and brutal seas, while being offered and declining freshly baked pies, he receives further ridicule by his father, ‘What bloody fool chooses to go live upside down in a place inhabited only by convicts?’

Roger awakes in a clammy sweat. Silence. Fred must be asleep. No frantic whining. Good. His heart still races at the fading thoughts of throwing up. Quickly he realises that he has run out of dreams but now dozes afraid to repeat his nightmares.

Roger’s oblivion is clinched by Sue’s brilliant observation at breakfast.

“You do realise that we won’t have any money to spend on the journey, either way we go. Perhaps the SS Wanna Be isn’t the best choice of transport. We’d be tempted to go ashore. Spend money.”

“We’ve never had a holiday.”

“I know. Neither so much as a sun lounger in the rain, nor a dog eared book to read over a period of days.”

“Join a book club that only reads wine labels, and get guzzling, Sue. Maybe we’ll need a holiday after we arrive just to recover from all this?”

“Alright, now we’re aware that Poseidon is possibly not on our side; we don’t need any more soothing music.”

Roger’s mental awareness is ranging from that of a butter knife to an over-ripe plum, but they are on it like a fat kid on a cupcake.

With their forms, certified copies of birth and marriage certificates, employment records, proof of financial standing, or as in their case severe lack of, a request to fly and last but not least payment of a whole £10 each they drive to the local post office and send the hefty envelope to the Government half eagerly and half with a slight feeling of trepidation.

Quite quickly for a government department they receive a letter back.

“Might they have tired of sitting on their fat arses all day bending paper clips?” Roger announces, “Hey, look at this,” Roger is dumfounded, “it insists a personal appearance is mandatory, no excuses, or our application will be cancelled forthwith. All four of us have to attend.”

As usual, Roger is up early, although Sue is unimpressed with his horizontal jog before their important meeting.

“Not the best of timings, you selfish bastard,” she mutters.

Roger feels nuttier than a Snickers bar. Moreover, he realises to boot that outside it is a miserable day trying to rain but cannot. It is cold, windy, and bleak as an embittered ex-wife. The tightening of his scrotum only added to Sue’s idea of an uneventful day!

“We need a bigger car.” Roger groans. “I’m carrying enough gear to collapse a donkey and it’s only just a London meeting.”

“Be grateful they don’t want to see Fred,” Sue replies, buzzing around like a frantic worker bee.

Roger grins, “Fred, you lucky hound, you’re staying home. See? Today the dog does get the bone.”

Pooch Fred is excited, hoping Roger will leave the cathode ray tube on. It is his only source of warmth when they are out.

At Australia House, they are warmly greeted by a charming man whose stiff wattage of smile almost blinds them. He is taller than Roger, sporting the style of parting that only a fretsaw down the middle of his crown could achieve.

Fretsaw shows them through the reception area with pride. Plush as any bank’s HQ it has more locks than the Bank of Scotland.

“So you’re applying to go to Australia,” Fretsaw’s big wattage smile lights their way.

“Yes,” Roger replies, thinking it’s bloody astounding he realises that’s why we’re here.

They see many security guards.

“Why all this security?” Sue whispers to Roger.

He whispers back, “Dunno! With only a few Victorian oil paintings on the walls of buttoned down girls, what’s to steal?”

“Thanks to their overzealous cleaners the place is as clean as a nun’s drawers,” Sue giggles, “but why are our ears being assaulted with boring piped music by Muzak?”

“Agreed. Why don’t they play Waltzing Matilda?”

Briefly meeting Fretsaw’s boss, Sue smiles like an actress auditioning for a coveted role. He is trim and fine boned, immaculately dressed in a suit the colour of claret wine; handsome with a square jaw, dark hair, and broad shoulders.

When he speaks, he sounds pompous. “Oh, you’re the pest man.”

The way Pompous said that sounded synonymous with lunatic vermin. “I’m regional manager for a specialist pest control company,” Roger corrects cheerfully.

“Quite so.”

Pompous does not sound Australian; he has the kind of voice shaped by Sandhurst, the Guards, and a lifetime of drinking Pink Gin. His dulcet, educated tones could make it worth listening to a shopping list recital. When he smiles, he exudes an air of designer barbed wire that makes Roger feel about as conspicuous as a Great Dane at a cat show.

In demand are painters, bricklayers, labourers, steel workers — not fancy arse pest controllers.

Sue is tapping her fingernail against her front teeth. Nice nail. Nice teeth. She is melting next to Pompous as surely as a butterscotch chip into a warm, sweet cookie.

Female staff busily tap away at typewriters. The younger ones wear blouses unbuttoned to show some cleavage. Roger appreciates their effort while getting a stern look from Sue. Others run around with important looking folders.

“Maybe they contain their advertising budgets,” Roger comments to no-one in particular.

The staff have their special smiley faces on but offer little output. It becomes obvious they understand everything really, really well until they are asked a question. Any question. This directs Roger and Sue back to Fretsaw who slips into auto waffle, or suddenly becomes deaf.

Eagerly Roger pursues each of their carefully thought out questions about Perth in the fervent hope that their six Pools numbers might magically come up, but Fretsaw is unwilling to part with more than smiles that do not reach his eyes.

“I don’t think they know one end of a dog’s bowl from another,” Roger lowers his voice to Sue, “and in addition may they be culturally unaware?”

“They’re about as bright as post codes,” Sue opines quietly. She is annoyed. “If they can’t answer even our simple questions, and everything they want to know about us has already been detailed on their forms in triplicate. Then why are we here?”

Roger, putting on his hopeful smiley face, speaks to Fretsaw, “Here we are, brimful of questions for the experts, and no-one seems to know much about anything.” He pleads. “What about property values?” He pauses. “A guide would be helpful. Are we likely to be able to replace what we have here, with a similar mortgage? Can we get an indication of median property prices?”

“Our house’s value represents about quadruple Roger’s annual salary.” Sue cuts in, “Any comparisons would be helpful.”

Fretsaw thoughtfully projects, “Australia is a very confusing place. Most staff here are not Australian and the few that are, come from Canberra.”

“Is that why you know nothing about Perth?” Roger asks tentatively.

“Australia is such a huge landmass it takes up the major part of the southern hemisphere.”

Fretsaw has a smile, the beam of which resembles that of a Jehovah’s Witness who has just added a brand new member to his congregation.

“In the outback many children have never seen the sea. They’ve grown up without television in towns little more than T-junctions or a wide spot in the road. Vast stretches of major highways are little more than dirt tracks. If you break down you could be stuck for days. Jobs could be few and far between. Red dirt country. I’m sure you’d be more suited to city life in our nominated areas.”

Roger is thinking, Better than Bum-Fuck-Idaho or the never-never.

He nods in agreement, “Attractive though country life could appeal to our inner pioneer spirit, I’m sure you’re right. City it is but that’s why we nominated Perth. The brochure states it’s the Capital City of Western Australia.”

Sue is thinking, Can it get any less rural than that?

“Put another way,” Sue adds with a smile, “we prefer our milk delivered from a bottle rather than a teat.”

Fretsaw begins nodding enthusiastically, “Quite so. Western Australia, indeed Perth is its capital. It’s too far from anywhere to be really relevant.” He pauses. “I’m not even sure if they have television yet in Perth.”

Roger turns facing Sue, “That answers our question about television programs. No more Ena Sharples or Len Fairclough of Coronation Street.”

“I think they have 240 volt electricity in Perth.” Fretsaw is shaking his head, “but I’m not certain, you understand.” He is speaking softly, almost as if life is one big conspiracy.

Fretsaw then blows a cloud of nicotine that even the French would be proud of but Roger is about as shitted off as any Frenchman could be about now.

“We might as well be talking in Korean for all the assistance we’re getting,” Roger groans to Sue.

“He’s about as much use as an ashtray on a motorbike.”

They both chuckle.

“They’re totally fucked when we ask them any questions related to Perth. In fact anywhere outside of their nominated areas might as well come from Planet Sock.” Roger whispers.

Roger shakes his head, if only to release steam building up in his ears, “They may know how to fill a BOAC 707 but maybe they’re a long way off knowing what to do with the people after they arrive?”

Sue keeps nodding. If she is not careful, her head might fall off with the repetition.

“I bet you it’s because of their White Australia Policy. I’m convinced they only ever wanted us here for a visual.”

“You’re right you know. I bet a pound to a penny if we’d had so much as a tinge of anything other than pure unadulterated snow in us, that would have been the end of it. Not even allowed to step over the threshold here. I wonder who would have greeted us instead of Fretsaw?”

“The Ku Klux Klan, perhaps,” Sue opines.

“Have they said, yes?”

“I don’t know, have they?”

Roger asks Fretsaw another question. “Where’s your boss?”

He casually scans the area. “No-one ever knows the answer to that question,” he smiles.

“Maybe we should get going, Sue?”

“But we’ve only just arrived.”

Fretsaw thinks of something. His voice, barely above a whisper, is irrepressibly cheerful, “If you’re accepted under the migration scheme your journey will be seamless. Remember to take nothing and carry as little as possible on your flight, as BOAC supplies everything. That includes baby food and nappies on the plane.”

Sue gives Fretsaw her generous smile. “That’s wonderful. I was worried. It’s such a long way and how much to carry?” her voice tails off.

Fretsaw beams. “Absolutely. Once assigned everything will be taken care of including accommodation. Guaranteed.”

“Anything else?” Roger prompts eagerly.

“According to our government rules everything has to be sold and finalised before you leave. You can understand the merit of that. No unfinished business to be left behind. You’d be surprised how many people flee Down Under to avoid commitments here.”

“Absolutely,” Roger enthuses, “no loose ends.” Roger’s insides are a little less confident than he is showing.

“Yes and if you have any specialised kitchen equipment, like say a technologically advanced kitchen cooker. Please ship it out. That sort of paraphernalia is in short supply Down Under.”

Conversations continue but have long, pregnant pauses that make Roger and Sue feel uncomfortable.

With their visit completed, their new friends at Australia House appear content in the knowledge that they are not black fellas in disguise.

Fretsaw has one final piece of paperwork to be signed and witnessed.

“Both of you press hard, please,” he instructs, “as the bottom copy’s yours.”

Sue manages to sign her name without falling over in a dead faint.

Roger mumbles to Sue as they head out. “Maybe his eyes are brown because he’s so full of bull shit? Getting worthwhile information here is like trying to get Cork out of Ireland.”

“That man can say absolutely nothing and make it sound as strong and noble as the Ten Commandments.

Did you pick up his comment about people migrating Down Under to run away from their commitments?” Sue asks, her conspiratorial tone sounds concerned.

“Yes, but it hardly applies to us, as father’s bankers have never contacted me.”

Sue mouths the words to Roger, “Good, then let’s leave quickly before they do.”

Outside another downpour is well into its stride. Rain pelts down in heavy sheets. For a while, it bounces off the pavement like one long drum roll.

“I wonder if it rains much in Australia.” Sue yells above the din. Roger merely shrugs.

“For tail end of summer the wind is bitterly cold.”

Roger cannot see the children thanks to their bundles of clothes. They resemble Michelin Men as they hurry to their car to make their way home.

After their visit to Australia House, they receive a registered letter.

“Might it be a change of heart about Fred?” Sue opines.

Roger frowns. “Not likely, let’s open it and see.”

He scans the letter, with Sue leaning heavily across his arm.

“What’s it say?” Sue asks anxiously.

“It states they don’t like our preferred destination of Perth.”

Their disappointment is palpable.

Sue’s face is as if she has secured a ticket to a Rolling Stones concert only to be told at the last minute that it has been cancelled.

Her face drains of colour. “So, what’s our next move?”

Trying to appear cool, calm, and composed when he feels none of those things Roger ponders their tabletop at length.

“Why that damned harpoon to my brain and on a day when it’s already suffering impaired activity.” He whines on. “Why us?”

Sue grabs his wrist with surprising strength; her voice is phlegmy, “All is not lost.”

“Maybe Fretsaw and the way he avoided questions about Perth was a clue?” Roger ponders.

“Or, if he saw the content of this letter, after all it is from another department, might he be as surprised as we are?”

“Don’t call him to try and find out,” Sue cautions.

Roger nods in agreement. “If there’s one thing Dad instilled in me, it was trust no-one.”

“I’m guessing that made for some interesting Sunday lunches?”

The letter expressed in polite terms how someone with Roger’s qualifications, or lack of them, would be better placed in one of their Eastern States. They gave the following choices:

1. Sydney 2. Adelaide 3. Melbourne

“Now what do we do?” Sue asks.

Out comes their only map, again.

“Its use is proving as reliable as my bowels,” Roger jokes.

In a state of shock and disappointment, they stare stonily at the dot on the extreme left that represents Perth. They then traverse the latitude from Perth in the West across towards the Eastern States. They double-check their letter.

“Seeking is the goal and searching will be the answer,” Roger sounds totally without conviction.

“Yes,” Sue confirms, “it’s written — Eastern States.”

After attempting to drown their sorrows about Perth being a no go, Roger has a shot at drawing a straight horizontal line across the map from Perth in the west.

“Look,” Sue is cheering up a little, “the line you’ve drawn sits just below a place in the east called B-R-I-S-B-A-N-E that’s Brisbane, capital city of Queensland.”

Looking at each other Roger snorts, “Climate wise it’s a no brainer, being further north, and nearer to the equator, it has to be the right side of warmer than Perth.”

Sue is thoughtful. “I’m not sure what to do? We don’t want to upset our chances.”

“They say Eastern States. Brisbane, my Love, is Eastern. Actually, you can’t get any further east than that, or you’ll be in…the drink.

Look, we shouldn’t get frustrated by these Australian rules one, two, or three. They say east but don’t mention Brisbane. How’s about we hedge our bets.”

“How?”

“I’ll attach a hand written entry; ‘Sirs, we respectfully request we be considered for Brisbane—please, blah, blah, blah!’”

They send their missive away. Days slowly trudged into weeks.

Now they wait for the powers-that-be to sprinkle their pixie dust.

In the meantime buoyed by a non-response, which they find strangely encouraging they try to find out something, anything about Brisbane at the Norwich library. It is the largest in their area and Brainy greets them as old friends.

“Based on what we need to know today, I’d say these are good for lining budgie cages,” Roger retorts smoothing the newspaper with the palm of his hand.

“Admittedly, they’re old newspapers,” Brainy agrees with a wry smile, “but Brisbane is rarely mentioned. I deduce therefore that Brisbane must be a very plain and uninteresting place. There’s quite a bit about Canberra and Melbourne, though. Sydney gets a few mentions.”

After a while Brainy finds them a book that shows a small part of the Gold Coast in South East Queensland. On the map, it looks slightly more than an afternoon’s drive from Perth but on closer inspection Brainy suggests they might require taking a picnic lunch.

Sue who finally has her hands on the book is excited. “Look there’s a recent photograph. Oh, this is so much better than those black and white drawings of Captain Cook.”

Whoever had written the segment about the Gold Coast included a single colour photograph.

“A novel change from etchings of convicts in chains,” Brainy agrees amiably. Nodding like a Pekinese doll on the dashboard, he loans them the book.

At home, they do more than peruse. They study that photograph of a man hosing down the drive-way to a house.

Without question that photograph was never intended to provide the hours of in-depth investigation that Sue and Roger devote to it. The expression ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ comes to mind. Roger briefly scans the image looking for something of interest, like a woman’s cleavage or a dog doing something despicable in the background.

Sue dissects the picture with a considering look as if conducting an autopsy. “Other than being referred to as banana benders it clearly states: A fastidious Queenslander. That’s a bit unfair; it’s as if Queen-Z-landers are not overly popular with others in Australia. Why call him fastidious just because he likes hosing down his driveway?”

“A good point, if it is his driveway. Unless of course you don’t like Queen-Z-landers anyway.”

“The hosing down looks more like some sort of relaxation ritual. There are no obvious signs necessitating a clean down.”

“There’s a big timber house,” Roger chimes in. “Means it can’t be that cold, otherwise it would be brick. Wouldn’t it?”

“Not necessarily; colder places do have timber homes. At least he has reticulated water and apparently plenty of it.” Sue observes with excitement. “Look, he’s using a hose draped from what looks like a car wheel mounted on the side of his house.”

“Maybe he can’t afford a proper one, but it’s not a novelty him having the means to splash water around. There can’t be any shortage of water. Just makes you wonder sometimes how close an anthropologist’s deductions are…”

“He’s dressed in shorts, so we can assume he’s not freezing his nuts off.”

“Nor is the water icing up on contact with the ground and look, he’s barefooted.”

“He’s not starving either. His stomach’s sticking out over his belt. He looks overweight.”

“He doesn’t look wealthy by British standards but he can at least afford to eat well.”

“With a gut that size it’s unlikely he could out work me physically,” Roger adds optimistically.

“Unless he’s an Einstein in disguise hosing non-existent crap off his driveway?” Sue offers sceptically.

“As long as if he’s asked what he does on his day off, he doesn’t answer ‘celebrate Christmas,’ you might be right.”

Sue continues, “The sky’s a deep clear blue, look, see up there, a couple of brilliant white wisps of cloud, you can even see shadows on the driveway, from what look like trees.”

Sue is turning her head sideways to change the rotation of the image. “The grass is green, the other shrubs and flowers all look healthy. Huh, I just realised, he’s hosing a concrete driveway, oh, and look right down the bottom here, you can see the road, it’s black bitumen, not dirt.”

Sue’s eyes are alive and dancing as she devours every minute detail of the photo. The whole scenario captured in a nanosecond by some passing photographer of the time.

They remain enthusiastic but worry creases their faces without word from Australia House.

Sue is convinced, pressing her white-knuckled fists to her mouth. “You’ve blown it. Oh, why did you have to go against their wishes?”

Roger is pacing back and forth like a caged animal. He turns. Her eyes are glazed, as if she is elsewhere. He knows that look well. He has seen it in the mirror often enough after the failure of the family business. Four years of his life working twenty-four seven for food and keep without wages only to be kicked out by the receiver’s liquidators with nowhere else to go, except more of the same.

“I hate many things, Sue, but most of all I hate waiting for something to happen. This is like all retch and no vomit.”

“You’ve been giving this a lot of thought, haven’t you?”

“Yes, but only once a day,” he smiles, “just all day long.”

The postman knocks on their front door with another package too large for the letter slot.

“Hello,” he says cheerily to Sue, “I see you’re going to Australia then.”

The age old ritual of the Postie knowing everything about everybody is how Sue and Roger first learned going Down Under.

The package contains, amongst the obligatory government paraphernalia and crapola, four air tickets to Brisbane, departing 13 March, 1971 on a BOAC charter flight from Heathrow.

Sue starts doing crazy little dance steps. She looks as excited as a small child waiting for Santa Claus.

“Say something.”

“Wow!”

“Say something else.”

“I’m gobsmacked. You know what this means.”

“No. What does it mean?”

“This means the staff at Australia House decided to wait until after James’s first birthday.”

“Why the hell would they do that?”

“Because he’ll have a seat to himself on the plane.” Excitement crackles off Sue like static electricity, “Don’t you see? That qualifies us for an additional luggage allowance.”

Roger is amazed. “I don’t believe they did it on purpose, but, I’ll go with it. We’re now well and truly government sponsored migrants, then.”

That night Roger snores like a contented hippo about to give birth. Snoring and grunting in brute slumber, instead of dreaming about Seal Flipper Pie, Roger is dreaming of when nothing goes right, try going left.

Thanks to the postman spreading their unbridled news, Sue is approached by local women wanting to buy items they might not be able to take with them.

For the next week, Coxwell swarms with villagers, who are agog. Nothing this exciting has happened since 1942 when Annie Bancroft, a chambermaid at the Maid’s Head Hotel in Norwich, was bludgeoned to death.

“Look at all this stuff,” Sue’s surveying their contents strewn over the lounge room, “looks like the inside of King Tut’s tomb.”

“Pity it’s not as valuable.”

Their neighbour Doreen is first to put dibs on their late model Silver Cross pram.

Roger is on his hands and knees busily cleaning the wheel rims level with Sue’s thighs.

“I hope you know what you’re doing down there, Roger,” Doreen says coyly.

“That’s just what Sue always says,” Roger offers with an awkward side look at Sue.

Cecilia is hot on Doreen’s heels wanting children’s toys. Her friend put dibs on pots, pans, and glassware. Someone suggests Roger buy a mower so he can sell it to them, cheap.

They are making new friends from everywhere.

The downside to their move is the Australian Government does not consider Fred a suitable candidate for Down Under. The high costs involved in Fred becoming an Aussie canine include six months in quarantine.

Roger shakes his head, “That and his live freight passage make the costs of taking him highly prohibitive.”

Their decision has nothing to do with Fred chewing shoes or digging up the vegetable garden next door.

“Maybe we should get professional advice?” Sue suggests.

Dr Doolittle, their local veterinarian, is about as pet friendly as Hyde Park. The decor hints at old fashioned values and efficiency. The view from the surgery window is not great: a variety of angles, gables, ridges and tiles of the old high street are splattered in bird poo.

The vet and Fred are in raptures over each other every visit.

Dr Doolittle frowns. “I’m of the opinion that Fred should be put down!”

Sue is horrified.

“I have trouble accepting that,” Roger replies evenly.

“Well Roger, the cost of taking Fred with you would bankrupt most people. Do you have time to sell him or give him away? No. Well, I’ve stated the obvious really.”

Dr Doolittle cups Fred’s face in his hands and speaks in that chirpiest of voices that people use when talking to animals or babies.

Back home their mood is glum.

Sue is mournful, “If we had a goldfish, then that has to be killed, too.”

“It’s one thing to take Fred down to the vet surgery to lose his manhood,” Roger explains gloomily, “but now this! I can’t understand why a family doesn’t want to take him for free.”

“We’ll ask around again, and see if we can find another family for Fred.”