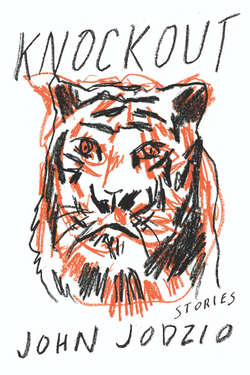

Читать книгу Knockout - John Jodzio - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGREAT ALCOHOLIC-OWNED BED AND BREAKFASTS OF THE EASTERN SEABOARD

Me and the boy are out back shooting holes in the rusted-out johnboat when I hear the wheels of a suitcase bump over the cobble of the front path. It’s still light out and I’m halfway through my bottle of Beam, which, if I’m pacing myself correctly, means it’s five or six o’clock.

“Hop to it,” I tell the boy.

The boy isn’t mine. He’s my dead wife Sandy’s, from her dead ex-husband, Jerold. He’s blond haired and fine boned. The house we live in is a weathered Victorian that Sandy and I bought to fix up into a bed and breakfast. I got about as far as painting the sign out front with a couple of intertwined roses and the word “Bed” before Sandy died. There was talk after the funeral that the boy would go to live with some of Jerold’s relatives in Ohio, but when it came down to it none of them would actually drive down here to pick him up.

I watch the boy skip off. He’s eleven and he runs like he’s got a corncob up his ass. I try not to hold that against him. I don’t run like that and I do not look like him in the least, but he hasn’t ever called me anything other than Dad. I’ll tell him about his real father very soon, I suppose. I’ve thought the conversation all out. I want to do it when I am sober, which usually means right away in the morning. I’m planning on telling him over steak and eggs. I’ll sit him down at the kitchen table and tell him I’ve got something important to say. He’s smart, this boy, very inquisitive. I know how the conversation will go. He’ll start in with the questions before I’ve even started saying what needs to be said.

“Is this the sex talk?” he’ll ask.

“More or less,” I’ll say.

I lean the rifle against the woodpile and walk around to the front of the house. There’s a woman standing there. She’s in her late thirties, wearing a baseball hat and sunglasses. I can’t see her eyes, but I can tell by the tilt of her head she’s glancing up at the gable, looking at how it’s leaning some, not ready to fall or anything, but nowhere near straight. The boy does exactly what I’ve taught him to do anytime someone shows up on our doorstep—he grabs her luggage and hauls it up the stairs before she can change her mind.

“What brings you here, ma’am?” he asks.

The boy is having trouble lifting her suitcase. He’s bouncing it up the stairs, so I grab onto the handle and help him out. I can understand why he’s struggling. It’s heavy as hell; it must weigh a hundred pounds.

“Are there gold bars in here?” I ask the woman. “Or a dead body?”

The woman gives me a wincing smile. She hardly has any legs under her. She got these stubby things, hardly worth a glance. Sandy, now that was a lady. Long legs and a mouth that could let out a deep and powerful moan.

“I’m writing a travel guide,” she says.

I don’t know what that has to do with a heavy suitcase, but I don’t press her. I’ve only got two rules to stay here. Number one, you pay what you owe, and number two, don’t shoot, stab, or poison me or the boy.

“I’m staying at all of the B and Bs up and down the Eastern Seaboard,” she says. She takes another look up at the roof, right near that hole in the soffit where the raccoon lives. “And this is on my list of places to review.”

We haven’t had a guest in a month, but the boy hasn’t forgotten the protocol. He asks for a credit card for room deposit and incidentals. He runs an imprint on our credit card machine. He looks at the name on the card, hands it back.

“Thank you, Ms. Brunell,” he says.

The boy is polite and does well in school. When I go to teacher’s conferences I can’t get his teachers to say anything bad about him. He does his homework, shares, makes friends easily.

“Can I have a room with southern exposure?” Ms. Brunell asks.

I pluck a room key from the board underneath the till.

“Let’s put Ms. Brunell in the Grover Cleveland Suite,” I say.

The boy likes presidents so we named all of our rooms after the fat ones. While the Grover Cleveland Suite isn’t as big as the William Howard Taft Room, it’s the quietest. If I would actually get around to trimming the dogwood out back, the room would have a great view of the river. Right now about the only thing you can see is the swing set in the backyard of my neighbor Masoli’s house. I really hope Ms. Brunell takes into account all the potential we have here. I hope she can see what we could become, even though we won’t.

The boy shows her to her room, and I hear Ms. Brunell drawing a bath, the pipes hissing and clacking.

“What do you think she’ll write about us?” the boy asks over the noise.

“Only good things,” I yell back.

How Sandy died was a dumbass thing. One night, on her way to meet me at the Keg n’ Cork, she tried to go around a railroad barrier. Her car was speared by the front of the train, pushed all the way through our town, sparking and screeching, right past the courthouse and right past the barstool where I sat waiting for her. She went past the Riverwalk Mall and into Halsford before the conductor could get that fucking train stopped. The police report said she died in Halsford, but the coroner’s report said that she died on impact, and while it can’t really be both, it is.

The boy was a year and a half when that happened. Up until that point, I hadn’t done much for him other than read him some bedtime stories and change the occasional diaper, but over the next few years, I did it all. My grief was not helped by the fact that each time I looked at the boy’s face I saw Sandy, and each time I thought of Sandy a curl of pain rippled across my chest—a feeling like something had been torn out of me and then that very same thing had been rolled in glass and shoved back in me upside down.

“That’ll go away soon,” my sister, Marlene, told me.

“If it was going away it would have gone away by now,” I told her. “I’m stuck with it.”

I stopped drinking after Sandy died, but when the boy started kindergarten, I started up again. I ended up drinking on the job and I got fired when I cut off the tip of my pinky with a band saw. This started a long period of the boy and me making due, of one day melting into the next, of the occasional guest or two stumbling onto our doorstep. By now, the boy and I have developed a solid routine. He knows he can count on me to make him breakfast and hand him a bag lunch on the way to school. When he gets home, he knows that he’ll be the one making dinner and helping me up to bed.

The boy chops up some onions for a stew and I go back outside and shoot some more holes in the boat. While I’m out there I see Masoli and his six-year-old daughter, April, smacking a beach ball back and forth in their front yard. When Masoli first moved in we got along great; I lent him my socket set and he lent me his hedge trimmer. One night I invited him over for a barbeque. While our kids played together, we ate ribs and talked about how my wife was dead and how his ex-wife was batshit crazy.

“After I got custody she was so angry she lit my ’77 Corvette on fire. I spent ten years restoring that car and she burned it to a crisp in ten minutes.”

For a while I imagined Masoli and me becoming good friends, drinking beer, and shooting the shit. I pictured us commiserating about single parenting and keeping each other sane. None of that happened. A few nights after that barbeque, I got blind drunk and walked into Masoli’s front yard without any pants on and he punched me in the face. We haven’t talked since.

I hear April squeal as Masoli bats the beach ball way over her head. Sometimes when they’re outside goofing around, I grab the boy and we stand on our driveway and laugh really loud so Masoli knows we’re having fun too. I go inside now and pull the boy onto the porch and we fake laugh loud enough to drown out April’s giggling.

“You ready for dinner?” the boy asks when we’re finished.

I pump a couple more shots into the hull of the boat, and then I pick up a few of the bigger rocks from my driveway and chuck them over into Masoli’s yard so they’ll fuck up his lawn mower.

“Now I’m ready,” I say.

The next morning I make biscuits and redeye gravy. Sandy and I started dating when we were working together at a diner in New Orleans called the HunGree Bear. She was a waitress and I was the cook. We lit out of there right before Katrina, grabbing everything we could and throwing it in the back of my truck. We got out of there just in time, but we couldn’t find our dog, McGruff, before we left. Sometimes at night I dream McGruff’s on one of those incredible journeys. In my dream, he always shows up on our porch with a bunch of burrs and sticks matted in his fur, thinner, but not all that worse for wear. I’ve been thinking about getting another dog for a while now, but for some reason I still think McGruff’s coming back. I don’t want him to be pissed that I thought he wasn’t.

“I trust your night was pleasant,” I say to Ms. Brunell as she sits down at the breakfast table.

“Pleasant enough,” she says.

She’s wearing a track suit. She still has on her sunglasses. I can’t tell if she’s got a decent body underneath her baggy clothes, but I’m leaning toward no.

“Are you going to look around town today or go hiking by the river?” I ask her while I stir the gravy. This is a good batch, thick enough to not run everywhere, thin enough to get into the nooks and crannies of the biscuit.

“I might lay low,” she says. “I’m not feeling the best.”

I put a plate of biscuits in front of her and she takes a bite. There’s a spot of mold on the wall above her head that I keep painting over but that keeps coming back.

“I wasn’t expecting much,” Ms. Brunell says, pointing at the biscuits with her fork, “but these are damn good.”

I wonder if she should be taking notes for her review, but maybe she’s got a better memory than me. I decide to try to be on my best behavior for however long she stays, drink less than usual. Maybe my breakfasts will be the thing that wins her over; maybe my cooking can make up for everything that’s fucked up around here.

I get the boy off to school and then I spend the rest of my morning napping under the dogwood. When I wake up, I see Ms. Brunell standing in the window with a pair of binoculars up to her face.

Great, I think, she’s into birds. Maybe we can take a stroll along the trail and I can point out where all the reticulated woodpeckers nest. Maybe we’ll take a walk through the marsh and I can show her that family of owls that lives inside that hollowed-out sycamore.

When I get back inside, Ms. Brunell is sitting in the living room in front of the fireplace, staring into its blackened mouth. I would love to light a fire for her, but a dead squirrel got stuck in the flue a couple of weeks ago. The smell isn’t that bad unless it gets really windy. Just in case she’s got a really sensitive nose, I light a scented candle.

“What other bed and breakfasts have you stayed at?” I ask her.

“I’ve been up and down the coast,” she says. “Tons of places.”

I mention a couple of other B and Bs around here—the Carriage House, the Mount Angel House, the Geffon-Buckley Bed and Breakfast. These places are clean and quaint, full of flowery wallpaper and potpourri, packed almost every weekend. Those places are how our place was supposed to turn out. I can only imagine what those places say about us if anyone asks. And I doubt anyone asks.

“All of those are on my list,” Ms. Brunell says. “I’m going to stay at the Mount Angel House right after this.”

“I saw you with your binoculars earlier,” I tell her. “There’s good birding around here. If you’re interested, I could show you some owls later tonight.”

I’m trying to go the extra mile for Ms. Brunell so she’ll give us a decent review, but I suspect she’s used to better offers than dumb-ass owls. The fancier places probably pull out all the stops; give her gift baskets full of fine chocolates and cheeses to help her remember her stay.

“Yes, owls might be nice,” she says to me as she lies down on the couch and closes her eyes.

I’m shooting some beer bottles off the back fence with the pump rifle when the boy comes home with his report card. The thing is perfect, straight As. His teachers have filled up the comments sections with great things about his attitude and work ethic. I hand him a twenty from my wallet. I tell him to spend it on something frivolous, like candy or fireworks, like I would’ve when I was young.

“Sure,” he tells me. “Okay.”

Even though he says this, I know he won’t spend it on anything good. He’ll tuck it away in the shoebox he keeps under his bed for household emergencies. If I want him to have fireworks or candy, I’ll probably need to buy them myself.

While we’re resetting the bottles on the fence, we hear a loud squawking noise near the house. The boy and I run over and see a hawk fighting with the raccoon that lives up in the soffit. A family of hawks nested there before the raccoons and now I suppose one of them has returned to find someone else has invaded their roost. The hawk and the raccoon are really going at it, the hawk flapping and screaming and the raccoon clawing and hissing. I fire my gun in the air to break things up, but it doesn’t do anything. I fire again, this time a little closer to them, and my shot scares off the hawk, but I accidentally hit the raccoon in the gut. It scrambles back inside my roof and then it starts to bellow. The boy and I watch as a shitload of raccoon blood starts to pour out of the soffit, a river of red running down the side of the house, right over Ms. Brunell’s window.

By the time the boy comes back with the ladder, the raccoon is dead and the house is caked in blood.

“Keep Brunell busy,” I tell him. “Don’t let her go back to her room until I can get this crap cleaned off her window, okay?”

I grab a bucket and a sponge and climb up the ladder. While I’m scrubbing, I can’t help but look inside Ms. Brunell’s room. There’s a black bra hung on the doorknob. Her bird-watching binoculars are lying on the bed. There’s other stuff there too, weird things. Laid out on the desk are a dozen pictures of Masoli’s daughter, April, when she was younger. There are also a few pictures of Ms. Brunell, Masoli, and April on the desk—one of them standing in front of the Grand Canyon. In another, the three of them are standing on the deck of a cruise ship with the endless blue of the ocean behind them. Ms. Brunell’s suitcase is open on the floor next to her bed and I can see now why it was so heavy—it’s filled with a couple of handguns, a tent, some cans of food. It’s taken me a minute to connect the dots—that Ms. Brunell is actually April’s mom, that she’s Masoli’s ex-wife, that she’s here to steal April—but when I do, I quit cleaning the blood off the window and scramble down the ladder to tell Masoli.

Before I can get over to Masoli, he starts up his lawn mower. And while I’m running toward him I hear a loud crunch, one of the rocks I’ve tossed into his yard hitting the blade. There’s a puff of blue smoke and his mower grinds to a halt. Masoli flips it over, sees a huge gouge in the blade and a rock that matches the rock from my driveway. When he looks up, he sees me coming toward him—drunk and out of breath, raccoon blood smeared down the front of my shirt. April is jumping rope in his driveway. When she sees me, she stops.

“Turn your ass around,” Masoli tells me.

I keep walking toward him. He tells April to go inside and then he marches toward me, his hands already clenched into fists.

“Get out of my yard now,” Masoli says.

“Hold on, hold on,” I say. “I need to tell you something.”

I hold my palms up to show him I mean no harm, but Masoli doesn’t care. He shoots his right fist through my palms and hits me in the mouth. I feel my teeth dig into my tongue and the bones in my jaw slide upward and I taste blood. I grab my face and topple to the ground in a lump.

As Masoli is walking away from me, the boy flies out of our front door. He screams as he leaps on Masoli’s back, flails at Masoli’s chest with his spindly arms. The boy gets in a couple of good shots before Masoli tosses him off and stomps back inside his house.

“That motherfucker is going to get his,” I tell the boy as we lie there in the grass. “Don’t you worry about that.”

“Okay,” the boy says. “Sure.”

There’s conviction in my voice, but not in the boy’s. I can tell he’s tired of defending me. I want to explain to him how this time was different, how my intentions were pure, how what happened was unprovoked. I want to tell him I was trying to help but things went sideways. I keep my mouth shut because I can tell that no matter what I say, he’s already grouped this together with all the other dumb things I’ve done.

After the boy is in bed, I lie down on the couch in the living room. Around midnight Ms. Brunell comes downstairs. It’s windy outside; it’s getting ready to storm. The room is dark; she doesn’t notice I’m lying there. I could say something, try to intervene, but I don’t. I let whatever’s going to happen, happen.

After she walks out the door, I twist off the top of a bottle of Beam and pour out a couple of fingers into a lowball. I stand on my front porch as the rain grows harder, the wind stripping the leaves from the trees. At some point I know I’m going to need to go down to the basement and spread out bath towels where the foundation leaks. After that I’ll need to set a bucket in the upstairs bathroom to collect all the water that drips from the ceiling. Ms. Brunell is dressed in all black, black hoodie, black stocking cap. She pries open Masoli’s basement window with a crowbar and slips inside his house. When she slides out the front door a few minutes later, April is asleep in her arms. I watch her drive away and then I take a piece of scrap paper and write the boy a note that says “Steak and Eggs for Breakfast.” I write it in big, dark letters and I leave it on his bedside table so he’ll be sure to see it right away when he wakes up.