Читать книгу Blood Wine - John Moss - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеThe Message

Morgan and Miranda stood in the living room with Spivak and Eeyore Stritch. Morgan looked angry. Spivak seemed puzzled. He stared at Miranda with genuine concern, which was somewhat concealed behind his habitual scowl. His young partner seemed anxious.

“We’ve got a problem, Miranda,” said Morgan. “Your friend, they can’t find him.”

“What are you talking about?” she said, cocking her head toward the bedroom. “You can’t get more found than that.”

“Yeah, you can,” said Spivak.

“Someone’s in there,” Morgan said.

For a desperate moment she thought it was all a mistake, that it was someone else dead in her bed.

“His name is not Philip Carter. There was no Philip Carter at Ogilthorpe and Blackbourne, they’ve never heard of him.”

“Morgan, what are you talking about?”

“There’s no home in Oakville. No teenage daughters, no wife.”

For another weird moment, Miranda felt relieved; she would not have to bear the guilt for a widow’s grief or fatherless children.

“Your friend, he doesn’t seem to exist.”

“Is that an existential proclamation?”

“Listen to me. Philip Carter, his driver’s licence, his health insurance card, credit cards, they’re fakes.”

“No,” she snapped. “His address —”

“A Vietnamese variety store in Oakville. They met him once, he paid them, they forwarded his mail to a mailbox in Toronto.”

“But you know him, Morgan. For God’s sake, Philip is Philip.”

“We never met.”

She was incredulous. Morgan was so inextricably a part of her life.

“Never?”

“You never talked about him.”

“Really!”

“Okay,” said Spivak. “Enough true confessions.” He motioned Eeyore to come closer then turned to Miranda. “Where’d you meet this guy?”

“In court.”

“Lawyer, criminal, judge?”

“I met him coming out of a washroom.”

“Janitor?”

“Lawyer.”

“Women’s or men’s?”

“Me, I was coming out of the women’s. He was in the corridor. I walked straight into him.”

“In the courthouse?”

“Yes.”

“You were there for the Vittorio Ciccone trial?”

“I’m a witness.”

“Yeah, everyone knows you’re a witness.”

“It’s complicated.”

“Yeah, everything connected with Ciccone is complicated. Finding a dead guy in your bed, is that a Vittorio Ciccone complication?”

“Philip is a corporate lawyer. Was.”

“Drug lords need corporate lawyers, especially phantom corporate lawyers.”

“No, Philip didn’t know him.”

“It’s as dangerous to be for Ciccone as against him.”

“I’m neither.”

“You’re the link between a dead guy and a guy who kills people. You ever see him practise law?”

“No. How do you watch a corporate lawyer practise law?”

Spivak smiled, and the effort made him break into a rough, rising cough. “So tell me about the wife and kids?”

“He was married.” She refused to say he was “unhappily” married. “He had two teenage daughters.”

“You’ve seen pictures?” Spivak asked.

“He wanted to keep that part of his life separate.”

“From?”

“From the part he shared with me.”

“Generous man. You’ve known him for two months?”

“Nearly.”

“Not very well.”

“Who knows anyone very well?”

“Did you kill him?”

She felt rage choke in her throat and thought she was going to vomit again.

“Lookit,” said Spivak. “Why would a stranger use your gun to kill another stranger, mutilate the corpse with your knife — M.E. says he was gutted post mortem — and then scrawl with his guts on your walls, and oh, yes, with you sleeping through everything, not a mark on you?”

Silence.

“And one more thing,” said Spivak. “There’s gunpowder under your nails.”

“Am I under arrest?”

“Gawd no. I’m not even taking you down for questioning. But don’t leave town, as they say. You’re the prime until something better turns up. Sorry about the boyfriend.”

Miranda had known Spivak for years. He wasn’t a bad cop and he wouldn’t get in the way while she and Morgan conducted their own shadow investigation. The kid seemed agreeable, maybe a little odd.

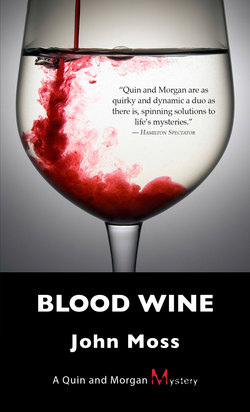

It was midday and they were alone. Morgan found a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the kitchen cupboard. A recent vintage, but with a fulsome aroma. He did not recognize the label; this surprised him. He poured them each a long drink, using crystal stemware he had never seen before.

Leaning side by side against the counter, they toasted in a grim salutation to the surrounding emptiness.

After a while, they toasted again.

“Here’s to old what’s-his-name,” said Miranda.

“Yeah,” said Morgan. “To Philip.”

“He brought this for a special occasion,” she said. She was cupping the tulip-shaped bowl of the glass in her hand. Morgan reached over, took the glass from her, then returned it so she could properly grasp only the stem.

She offered a wan smile of acquiescence. She could feel the warmth of her lover’s body, his hands, his breath.

The wine was the colour of arterial blood before it congeals. She sipped but it tasted raw, although Morgan was enjoying it.

“The prints on my gun, my prints should be all over it.”

Yeah, he thought.

“Ellen Ravenscroft, Morgan, she’d jump your bones if she could.”

“Or yours.”

“Nonsense, she’s straight. She’d eat you alive.”

“Yeah,” he acknowledged, gazing into the crimson depths of his glass.

“I thought I was falling in love,” she said. “God, I’ve been stupid.”

“Me too, sometimes. I married my biggest mistake.”

“At least you didn’t kill her off.”

“Divorce; a form of manslaughter.”

“How old am I?”

“Thirty-eight. Why?”

“Thirty-seven and change.”

He said nothing.

“You’d think I’d learn, Morgan.”

“Yeah.”

“This place is a mess.”

There was a stillness about her that he could feel like a shimmering at his temples. Her hazel eyes seemed resolute, her auburn hair was mussed as if she had just made love. Her lean body torqued sensually from the hips as she surveyed her apartment.

“I don’t want the ghoul brigade,” she said. “I’ll do it myself.”

A loosely knit group of volunteers who had lost loved ones to murder or suicide would confront their own nightmares by turning up after the investigators were finished, if summoned, to scrub blood off floors, scrape viscera from walls, clean furniture and rugs, do whatever had to be done. Miranda did not want to deal with the goodness of strangers.

There were professional crime scene cleaners. She had worked with them. They were good, but this was private.

“Morgan.”

“Yeah?

“How come I’m alive?”

I don’t know, he thought.

“Jesus,” she said, “it’s about me, isn’t it? Philip was collateral damage. Oh Jesus Christ Lord God Almighty. This was a message to me.” She smiled. “Swear and a prayer,” she explained.

She looked at Morgan, a recovering Presbyterian and avowed anti-theist. It made him uneasy when she swore. He mouthed some wine and swallowed.

“Amen,” she said.

“It’s not always about you.”

“Sometimes it is,” she said, then repeated: “Amen.”

The next three days went by in a blur. The minutes and hours, daylight and darkness, were undifferentiated in Miranda’s mind. Morgan had taken her to his place in the Annex. Corking the Châteauneuf-du-Pape with a downward blow of his fist, he had grasped the bottle by the neck, scooped up some clothes in a bag, escorted her to the car, and driven even more carefully than usual. He was acutely aware that she disliked his driving. She always took the wheel when they were together, but this was an exception.

While she stayed with him, he slept on the sofa. Incredibly, his random collection of her clothing included changes of underwear and enough variety. But she was uncomfortable being alone in someone else’s bed. She stayed for two nights and then went home because she was lonely.

Now she was gazing across the room at him in Starbucks, just down College Street from Police Headquarters. His back was to her; he was picking up a couple of cappuccinos. He turned and shambled over. She smiled. He was trying to look after her.

When the crime scene was declared open, he had gone back to her apartment and cleaned up, even scrubbed the scrawled blood from her bathroom walls.

She had been suspended with pay. He was posted to a cold case that he could work on his own, and which gave him the time to shadow Spivak and Stritch, since that was what the superintendent knew he was going to do, anyway.

“How are you making out?” he asked.

“Same as last time you saw me, eight hours ago.”

“Ten. I’ve got an update.…”

“On?”

“You, mostly.”

“Shoot.”

“Your prints were on the gun — which was definitely the murder weapon.”

“As expected.”

“And no one else’s. That’s okay, though,” he assured her. “Your gun should have been smeared with layers of your prints. But there was only one neat cluster. At least two rounds were fired. And there were powder traces under your nails.”

“We know that. I was at the range —”

“No, you weren’t at the range that day. It was a couple of days before.”

“Really? You checked?” She paused, trying to sort out memory from reconstruction. “Two days before? My head’s more messed up than I thought — there was only one bullet wound.…”

“Even Spivak agrees the prints were too neat.”

“So where’s the other slug?”

“Good question.”

“But two rounds were fired?”

“Only one bullet was missing from the clip, but forensics are sure at least two were fired. Whoever did this was meticulous, replacing the bullet.”

“What else?”

Morgan looked into her eyes and raised his cappuccino in a gentle salute.

“The kitchen knife, it was yours, it had your prints on it — of course — but no blood on the handle, only the blade.”

“Suggesting what?”

“Well, there’s more. Ellen Ravenscroft called.”

“And?”

“She says the gut wounds don’t match up with the knife. It has a serrated edge. At this point it seems a red herring.”

“And? You’re looking solemner and solemner. Spit it out, Morgan.”

“Well, you and Philip had sex.”

“Often.”

“That night, I mean. I wasn’t asking a question.”

“And?”

“You had sex with someone else as well.”

“What?”

“Seems that way.”

“Then someone had sex with me, goddamn it. Who?”

He shrugged, almost apologetically.

“Oh my God, Morgan. Can they tell a sequence?”

“You mean who was first? No.”

“It had to be Philip,” she said. “Then he was killed. Then his killer … while Philip was in the same bed.” Miranda gagged but stifled the rush in her throat to retch.

“We’ll get the bastard.”

Even with her gut clenched and her head reeling, Miranda acknowledged to herself that Morgan had sworn. A mild expletive, but for him an indication of formidable anger. She was glad he was on her side. Controlled rage was a powerful ally.

She reached across the table and placed a hand over his. “Morgan. Since I was drugged — they’ve established that, right. It was a GHB cocktail. Used for date rape — does that mean Philip had sex with me while I was unconscious as well as the other guy?”

“Miranda —”

“It’s okay. And it seems less likely that his killer would … oh Jesus, it’s sickening … get off in me with a bloody corpse on the bed. No, it had to be Philip offering to share me, then he took a turn on his own, then he died.”

Her eyes were glazed and her voice was tremulous, but her jaw was set firm and she looked Morgan straight in the eye as she talked. He wanted to come around and hold her, but Starbucks was a public place and intimacy was not what she needed. She needed to feel his rage as the strength of affection. She did not need pity but love.

“Miranda?”

“Yes?”

“Once we’re through this —”

“There’s no getting through this, there’s only, you know, living with it.”

He wanted to ask her to marry him. He didn’t really want to ask her to marry him. He wanted to declare he would always look after her. He knew he could not always look after her. He wanted to tear her pain out by the roots. Without hurting her. He wanted to feel better about himself for having let this happen to his partner.

“Morgan, what is it?”

She was his friend. The best thing he could do was get on with the case.

“Nothing’s turned up about the man formerly known as Philip Carter,” he said. “We’ve checked with the Mounties, with the FBI, INTERPOL. Nobody’s heard of him, there’s no match for his prints. Total blank. One of over seven billion people on the planet.”

“Yeah,” said Miranda. “Not any more.”

“You okay with that?”

She almost laughed. “Well, no,” she said. “Not okay! On the other hand, maybe I am. If he wasn’t dead, I’d want to kill him.”

Morgan felt restless. He wanted to be doing things, not because he gave a damn about Miranda’s dead lover, whoever he was, but for Miranda herself, to get her life back so they could be partners again.

He wanted to help her, but he didn’t know where she was hurting.

Was it the horror? That would haunt the strongest of people, waking up beside a corpse with its guts spread over the mattress. Was it terror? That there might be a sequel, that she was a target? It seemed unlikely, not that it could happen but that she would let fear take hold. Was it grief for the death of her lover? He didn’t think so. Whatever grief there might have been was subsumed by anger. Was it rage for Philip having used her, even if she did not understand how? Was it revulsion, loathing for Philip or misplaced contempt for herself, for the depraved sexual abuse she had endured?

Miranda sat back in her chair and then projected with a sibilant hush her deepest desire. “The son of a bitch, the one I didn’t know, he’s the one I want dead.”

“We’ll get him.”

“I want him, Morgan.” She leaned forward. “I want him.”

Morgan had never heard Miranda talk this way. She had a cool intelligence that eliminated the emotional and the extraneous. Her mind was precise, and after three years with the RCMP following university and a decade working together on Homicide in Toronto, she knew how to use it with awesome dexterity.

“Dead won’t help. We want him caught.”

“Whatever. I want him dead. This is about me, not him.”

She wanted to tell Morgan to let himself go, that she needed the same passion he risked on inanimate things; she needed his ardour and fury, not spoken but felt deep in her heart and the depths of her mind.

“Okay,” he said. “We’re in this together.”

“Not quite. I’m the one waiting for the HIV results.”

“You okay?”

“Morgan, will you stop asking if I’m okay. Okay?”

Morgan felt helpless. He explained that the superintendent had given him his head, so that on the books he looked active. As for her suspension, apart from having had to turn in her semi-automatic, a pro forma procedure since it was already being held as material evidence, she was effectively on paid leave. And they were still partners.

“Rufalo’s turned us loose,” he said.

“And Spivak?”

“He’s good. Spivak will follow up whatever leads he can get. He’s promised to keep us informed. He’s not a small man, we’re not in competition.”

“About 290 pounds of not small. With his new partner, that gives us nearly a quarter of a ton of detective on our side. And what are we up against? I’ve been fucked and fucked over by phantoms.”

“Don’t make it worse —”

“Worse! You don’t like the word ‘fucked’? Does it make you squeamish? Jesus, Morgan, that’s what — I’ve been fucked. If ever a word was appropriate, that’s it, that’s what happened.”

Neither was prone to using vernacular. Kick ass, let’s roll, just do it wasn’t them. Fuck was a word they avoided, both feeling contempt for lazy diction, both alive among words too much to lean on stupid expletives.

Miranda got up and walked over to order two more coffees, this time not cappuccino. Often when Morgan was alone he had double-double, but with Miranda he always took black, no sugar. He actually preferred it that way. He could taste the coffee.

“So,” she said when she sat down again, “I’ve been ruminating for three days, perseverating, cogitating.”

“Which?”

“All three. Going over and over the details. Trying for the larger picture, waiting for something to emerge. So far, nothing but details.”

“Tell me things I don’t know.”

“Okay.” She paused. “He could have had an accent?”

“Who? Philip?”

“Yeah, we’ll call him Philip until something better comes up. It wasn’t so much an accent as an absolute lack of inflection. It was a little unusual. You know how sometimes Europeans speak English better than we do. Germans, especially. Like that. Except he wasn’t European.”

“What then? How do you know?”

“He spoke about Europe as an outsider —”

“And about Canada as home?”

“Canada and the States. It was strange. There wasn’t a border — Canada and the U.S., it was all the same. None of the usual Canadian edginess — benevolent antipathy — when he talked about Americans. And none of an American’s blithe indifference to difference when he talked about us. I remember thinking it seemed like a borderless sensibility and that it was strange, then I got used to it. I kind of liked it. I didn’t want to know too much. I didn’t want the emotional risk. He could have been either Canadian or American.”

“Or neither.”

“Perhaps. He was very cosmopolitan.”

“He knew good wines. I wonder where the Châteauneuf-du-Pape came from? I’ve never seen a label like that in Ontario — maybe the States. Could he have been Israeli?”

“Because he knew wines? An interesting connection! And no, definitely not.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“Morgan! A lady knows.”

“Yeah, okay, so, not Jewish.”

“Not Jewish. Let’s see, what else? Afghani? No, the Taliban never came up. So who does that leave us?”

“Where did that come from?” asked Morgan.

“What, the Taliban? I don’t know, whenever I think of relations between the sexes these days, I think of them. I mean, Morgan, watch the newscasts. Countries in that part of the world treat women like a different species. Crowd scenes, throngs in the streets, and no women. A sea of beards and burnooses, and impotent fists throttling the air — and not a woman in sight unless under a shroud. And don’t give me the freedom of religion crap — freedom for whom? The normalization of hatred for women, that’s what we’re seeing; fear and hatred of women. Even by women themselves. Especially by women themselves.”

“I wasn’t going to say a word. We live in parallel realities, get used to it.” He paused, curious about the direction their conversation had taken. “When I think of Afghanistan, I see those giant Buddhas crashing into clouds of dust a few years ago and, you know, it makes me ashamed and I think, God save us from religious zealotry.”

“An interesting prayer for an atheist.”

“Have you seen the pictures, giant hollows in the rock where the statues were, gaping holes spilling rubble? I’m ashamed on behalf of humanity.”

He’s more concerned about statuary, about cultural artifacts, than about women in shackles of drapery, in perpetual shadows. Perhaps it’s all the same.

“I made a list,” said Miranda abruptly, as if the clash of cultures were not under discussion. “You know, a list of the places we went for dinner or drinks, I gave it to Spivak.”

“He’s already checked them out,” Morgan responded. “No one recalls either of you. It’s like you were never there, like you didn’t exist.”

“That’s comforting. We were being unobtrusive, you know, too mature to flaunt our discretion.”

“What about the last night, nothing comes back?”

“No, yes.”

“What do you mean, no, yes?”

“Morgan, in the morning, there was a smell of almonds.…”

“And?”

“Hand cream, there must have been hand cream in the women’s washroom. I use aloe-based moisturizers at home, this was almond.”

“And this tells us what?”

“That we dined at an upscale restaurant. Large. The little spiffy bistros on the list have modest little bathrooms. I’d say we went to one of the major hotels. The Four Seasons, the Royal York. Almond is very old fashioned. I’d guess the Imperial Room at the Royal York.”

Before their eyes adjusted to the midday June sunshine, they had crossed the street and descended into the glossy underworld that spreads beneath downtown Toronto like an alternate universe, where weather and seasons are residual memories, office workers are on half-hour tethers, and retail is king.

From the Union Station subway stop they had direct access to the grand lobby of the Royal York and immediately found the maître d’ of the Imperial Room, who had just come on shift.

“Yes sir,” he said, directing himself to Morgan. “This lady was here a few nights ago.”

“Really,” said Miranda, “how can you be so sure?”

“Well, sir,” said the maître d’, still addressing Morgan, “the lady needed assistance in getting up from the table. It does not happen often, our patrons usually, ah, consume with discretion —”

“Hey,” said Miranda, taking him by the arm and swinging him around. “It’s me, I’m here. Talk to me.”

“Yes, ma’am, of course.” He turned to look at Morgan. “She was quite drunk, sir. I am sorry.”

“You’re gonna be a sorry soprano if you don’t focus,” said Miranda.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Where was I sitting? Who was I with?”

“Over there,” he said, nodding to a discreet table against a far wall. “You were alone with a gentleman, and then another gentleman joined you.”

“The bill,” said Morgan. “We need to see the bill.”

“Could I ask what for, sir?”

“You are assisting in a murder investigation.”

“Really? Well, of course.” The maître d’ was warming to his role. “If you will please come this way,” he said, and gently pulled his arm free of Miranda’s grasp. He led them into a small office and rummaged through a sheaf of receipts.

“Nothing,” he finally said. “There is no record.”

“There must be a bill,” said Miranda. “Perhaps we paid in cash.” As an aside, she said to Morgan, “He had credit cards, but he always used hard currency, sometimes American.”

“Of course,” said the maître d’. “It happens so seldom. Yes, you are right, Detective, just so. Here we are. Giovanni was your waiter. He will be here shortly. Let me see. You had very good wines; quite memorable, in fact. A bottle of Bordeaux with dinner, very nice, Château Cos d’Estournel, 1986. Excellent choice with your boeuf bourguignon. Myself, I might have preferred a sunny Clos de Vougeot, something a little less sinister, but, well, chacun à son goût. And when your other friend arrived, Dom Pérignon. A magnum. Memorable, indeed. Yes, of course. Excellent. Still, I do not understand … unless you drank more than your share, Detective.”

Morgan led her out into the main dining room. “Let’s get Spivak on this. He can arrange a sketch, maybe, of the third man, from the waiter.”

“I want to talk to him.”

“The waiter? Okay.”

They stood in the middle of the room, watching people cleaning up from the luncheon crowd, preparing for dinner.

“Does it look familiar?” Morgan asked.

“Yes.”

“Okay,” he said, surprised, “what do you remember?”

“Dancing with my father —”

“What?”

“I remember dancing with my father. We came here, just before my teens, a year before he died.”

“Really.”

“Mart Kenny was playing. I think he played here for years. My dad always wanted to see Mart Kenny and His Western Gentlemen, we heard him on the radio. But my mom wouldn’t dance with him. She could dance really well but she didn’t think he could, so he danced with me.”

“Was it the same?”

“As now? It feels like it was, but, you know, memory is fickle. No, I don’t remember being here with Philip. I don’t know, Morgan, it all seems familiar.”

She paused.

“The other man. He came before the Champagne … which is a perfect drink to conceal knock-out drops.”

“You could have been drugged before you got here.”

“Morgan, apparently I didn’t come in staggering … and it seems like I made quite a show when I left.”

They saw the maître d’ beckoning them from the side of the room. He pointed toward the kitchen.

“He just came in. Giovanni.”

They walked through the kitchen to a staff lounge. A tall, lean man with residual acne glanced at them and away, then again. He recognized them as police. Miranda and Morgan both knew instantly that his name was not Giovanni. There was no one else in the room. The man stood upright, confronting them, not belligerently but not intimidated.

“Where you from?” asked Morgan.

“Sienna.”

“You speak Italian, then? I speak Italian.”

The man’s eyes narrowed. “Yeah,” he said, “I do.”

Miranda smiled. Morgan’s bluff was being called.

“Go ahead,” said Morgan. “Speak.”

“What do you want?” said the man.

“What’s your name?”

“Giovanni.”

“When it’s not Giovanni, what’s your name?”

The man shrugged. “Malouf. Iqbal.”

“Which?”

“Iqbal Malouf, that’s my name.”

“You illegal?” asked Morgan.

“A little.”

“How’s that?” said Miranda.

“My visa ran out.”

“Recently?” she asked.

“Eight years ago. I’m married, I’ve got a kid. He’s a Canadian, in school.”

“Your wife?”

“Illegal. Lebanese, same as me. We met here.”

“At the hotel?”

“Yeah.”

“Have you ever seen me before?” asked Miranda.

“Sure, three-four nights ago, table by the wall. Dom Pérignon. You got drunk.”

“Did you know I was a cop?”

“No. You were some guy’s date.”

Miranda flinched. “And the others?”

“The guy who brought you, I don’t know. He was smooth, I’d say computers, maybe a stock analyst. Too calm for a broker. A tax lawyer, maybe.”

“Well, thank you,” said Miranda. “And the other one?”

“Never saw him before. Never saw any of you before.”

“What can you tell us about him, the third person?” asked Morgan.

“Nothing.”

“Think.”

“Nothing.”

“We’re not with Immigration.”

“Oh, come on, man. I didn’t see anything. He was just a guy. Mid-thirties, well dressed. He didn’t pay. The other guy paid, the guy who brought her.”

“Me,” said Miranda, exasperated with having to establish her presence again. “We came together, he didn’t bring me.”

“He paid. Big tip. Not too big, big enough.”

“The third person, the other guy, tell us more?”

“There’s nothing more.”

“Immigration …” said Morgan.

“He was Lebanese.”

“Good,” said Morgan. “How do you know? Did you know him?”

“No, he’s not from here. I’d have seen him around. Ethnics, you know, we stick together.”

“How do you know he was Lebanese?” Morgan repeated.

“I speak the language. I know.”

“Did the other guy speak Lebanese?”

“No, the Lebanese guy, he just said a few words. To me.”

“He knew you were Lebanese?”

“He knew I wasn’t Giovanni. I was just part of the ambiance, man. We didn’t have a relationship.”

“You’ve never seen him before?”

“Like I said.”

“Thanks for your help,” said Miranda. “Do you think you could give the police artist a description?”

“Yeah,” said the man. “But it would, you know, be generic. He just looked like a prosperous Lebanese guy about my age in good condition.”

“Did you go to university?” said Miranda.

“Yes, in Beirut, engineering.”

“Get legal,” she said. “Do what you’re trained for.”

“I make more money as a waiter,” he said with a shrewd grin. He smiled. “So you’re not going to turn me in?”

“No,” said Morgan.

“Thanks, man. Yeah, and he wore a big ring.”

“A big ring?”

“Like a sports ring, like if he won the Stanley Cup or the Boston Marathon.”

“A lot of gold, no diamond,” said Miranda.

“Yeah, like that.”

“We’ll be in touch,” said Morgan.