Читать книгу Country Ham - John Quincy MacPherson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 5

ОглавлениеGrandpa Dubya’s eightieth birthday celebration was that same night—Saturday night—and it began with a surprise. Carl showed up in the hearse to take Dubya and Cornelia to the Hillbilly Hideaway. Carl was not a blood relative, but Dubya refused to ride with Thom Jeff, and neither he nor Cornelia drove after dark anymore. Carl had the same proclivity to drink as Thom Jeff, but unlike Thom, he recognized when he should not be behind the wheel. So Carl recruited Ham to go with them as the designated driver on the way home. Dubya was fine with these arrangements; he liked Carl and enjoyed his offbeat sense of humor.

So Dubya and Cornelia were not surprised when Carl and Ham showed up to drive them. But they were surprised to see Mr. Ed.

“Whatcha drivin’ Carl?” Dubya asked tentatively. Cornelia didn’t say anything.

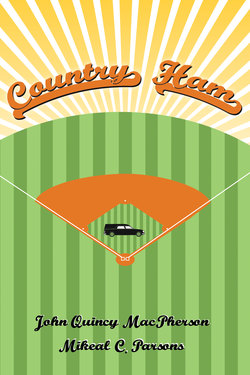

“My new hearse!” Carl exclaimed. “Well, it’s not new, but it’s new to me.”

“Happy birthday, Grandpa Dubya,” Ham said, trying to change the subject.

Dubya turned to Ham and gave a broad smile. “Thanks Ham.”

“Okay, everybody ready to go?” Carl asked.

“Where are we all goin’ to sit?” Cornelia asked. Ham hadn’t thought of that when he agreed to ride with Carl.

“Well, goin’ up, Ham can ride in the back. I’ll ride back there comin’ home.”

“That okay with you Ham?” Cornelia asked.

Before Ham answered, Carl said, “Why sure, Miss Cornelia, Ham has been back there before.” He turned and winked at Ham.

“That right, Ham?” Dubya asked.

“Oh, you know Uncle Carl, Grandpa.” Ham said as he headed to the back door of Mr. Ed.

When he opened the door, he saw Carl had removed the mattress. He tried to position himself between the grooves that would hold a coffin in place.

“Don’t raise up too quickly, Ham, you might hit your head.” Cornelia offered.

The ride to Hillbilly Hideaway was nearly an hour, but it felt like ten hours to Ham. He couldn’t hear the conversation in the front seat, but he did think he heard Al Green singing “Let’s Stay Together” on the tape deck until it was abruptly shut off, probably at Cornelia’s request.

By the time they got to the reserved room at the Hillbilly Hideaway, all of Dubya’s family was there, at least those still living. Aunt Nora, his oldest daughter, was there with her husband Wilson and their two children. They lived in Chapel Hill, and Aunt Nora was a deacon at Pullen Memorial Baptist Church, one of the first women to hold that position in the state of North Carolina. Thom Jeff and Nina were already there with Diane and Michael Allen, whom Dubya called “Mike Al.”

Dubya’s youngest daughter, Edith, was there with her step-husband, Bill Lovette, and her three boys. Bill was the younger brother of Fred Lovette, who started Holly Farms Poultry in North Wilkesboro in the 1940s. Thom Jeff said Bill and Edith were “well off.” Ham had gone to basketball camp with Edith’s boys when he was fourteen. They went to the camp at Campbell College run by Fred McCall and Press Maravich. UCLA Coach John Wooden was there and taught them how to put on their socks so they wouldn’t get blisters. But the star of the show was “Pistol Pete” Maravich. By that time, Pistol Pete had finished his storied collegiate career at LSU and was playing professionally for the Atlanta Hawks. Each night after dinner he would give a shooting and ball handling clinic in the Campbell gym, which consisted of him spinning and dribbling two balls every way imaginable and then shooting from way beyond the top of the key swishing jumper after jumper after jumper, all the while talking to the campers about shooting technique. He was amazing. Edith’s youngest son, Pat, had been the star of the Taylorsville High School team that year and probably could have played NAIA basketball. But he was called to the ministry and went to Freedom University over in Virginia to study with the faculty that the fundamentalist preacher Gary Farmwell had assembled. Pat, who was a couple of years older than Ham, didn’t think much of Ham’s church. “Way too liberal, Ham. God will spew that lukewarm church right out of his mouth come Judgment Day.” Ham and Pat got along fine so long as they avoided the subject of religion and especially religion as it was practiced at the Second Little Rock Baptist Church.

Conspicuously missing from the celebration were Dubya’s other three sons: Harold, Atwell, and Leo. They were missing because they were, well, deceased. Dubya believed it was the “MacPherson Curse” that had been put on him when he was a kid and was somehow transferred like original sin to his male offspring. When Dubya was eighteen—before he met Cornelia and therefore still drinking—he went to the Wilkes County Fair with some buddies. On a dare, he went in to see Lady Godiva, Palm Reader and Fortune Teller. Her reading was rather predictable and vague: Dubya would marry, have kids, lead a mostly normal life. When she finished, Lady Godiva said, “That’ll be fifty cents.” “I don’t have it,” Dubya confessed over his shoulder as he ran out of the tent. While still in earshot he heard Lady Godiva shout, “YOU will not live to see fifty, young man!”

Dubya mostly forgot the Curse until the night before his fiftieth birthday, when he told Cornelia about the Curse. “Oh Dubya, don’t be superstitious. Nothing’s goin’ to happen to you.” And, of course, nothing did. But the same could not be said for his male children.

The first to die was Atwell, the fourth of Dubya and Cornelia’s children (after Nora, Thom Jeff, and Harold). Born in 1932, Atwell joined the Navy at eighteen and was shipped off to Korea. Dubya and Cornelia were sure Atwell would die in the war, but he came home on furlough for Christmas in 1952. Like most of the MacPherson men, Atwell was a heavy drinker, a habit he continued to cultivate in the Navy. He went to a poker game in Asheville on Christmas Eve. The story that came back to Dubya was that Atwell was accused of cheating in the game and a heated argument erupted, which ended with Atwell being shot and killed. No one was ever arrested; Atwell was dead at the age of twenty. Dubya was sure it was because of the Curse. Rumor had it Atwell was holding Aces and Eights, the dead man’s hand, at the time of the shooting, but Ham was pretty sure that was just a tale told to embellish the story.

Leo, the next to youngest child, was thirty-four when he died, also the victim of a gunshot wound. He had followed a woman home from a local bar to her trailer park. Turned out the woman was married (or at least living with a man), and the man didn’t take kindly to a stranger standing outside his trailer in a drunken stupor yelling for his woman to come outside. The man warned Leo to leave, and when he didn’t he threatened to shoot him. And when Leo still didn’t leave, “by God, I shot him,” the man told the sheriff. Leo died hours later at Wilkes General hospital. Leo left behind a wife and two boys; all three were at Dubya’s party. Leo Jr. was a highway patrolman who had clocked Ham’s fastball with his radar gun.

The last to die was Harold at the age of forty-two. Harold was two years younger than Thom Jeff; he never married. Harold loved baseball, but he wasn’t a very good player. So he umpired all the games in the county—high school in the spring, American Legion in the summer, men’s open and church league softball in the fall. In his early twenties, Harold attended the Bill McGowan School for Umpires in Ormond Beach, Florida. The school ran for five weeks, and when Harold returned home Mr. McGowan arranged for Harold to umpire in minor league games across the state of North Carolina. After several years of umpire school and minor league umpiring at a pittance pay, Harold was called up to umpire in the American League in 1970. That year he joined the Major League Umpires Association (MLUA), a union formed to lobby for benefits for umpires. After the one-day strike of the championship playoff on October 3, 1970, the MLUA negotiated a labor contract that set the minimum salary of $11,000—over double what Harold had made during the season and more than he possibly could have hoped to make in North Wilkesboro. He umpired two more seasons. He died of a brain aneurysm on New Year’s Eve, 1972. Dubya was convinced Harold was another victim of the Curse. That left only Thom Jeff, who had turned forty-eight that February. Ham thought the deaths of the MacPherson men, with the exception of Harold, were due more to liquor and stupidity than to any kind of cosmic Curse.

The Curse was the last thing on anyone’s mind that night at the Hillbilly Hideaway. Along with family members, Cornelia had invited a large number of folk from church, and everyone was in a festive mood. After a dinner of salad, mashed potatoes, green beans, sweet corn, short ribs, and fried chicken—all served family style—the “program” that evening consisted of a few words from Cousin Magnum Fox and Brother Bob Sechrest. Magnum Fox lived in Seattle, Washington, but he made the trip to North Carolina at least once a year, usually at Christmas when he would recite from memory Dr. Seuss’s “The Grinch Who Stole Christmas” to all the children’s delight (“Every Who down in Whoville loved Christmas a lot / But the Grinch who lived just north of Whoville did not . . . ”). He was the family’s “genealogist” and would update everyone on his most recent discoveries of the MacPherson family history. Ham was sure that one year Cousin Magnum would announce that the first MacPherson had come to America on the Mayflower.

Tonight, as with every other visit he made to North Carolina, Cousin Magnum gave each child a silver dollar and to each adult he gave a copy of his latest reconstructed MacPherson family tree and a calendar—with the MacPherson crest and clan motto, “Touch Not the Cat Bot a Glove.” Ham was not quite sure what the motto meant; something about being prepared he guessed, since he knew from experience how badly a mad cat could scratch. Ham was disappointed that this year he fell into the adult category and got the family tree and calendar and not the silver dollar. Best Ham could figure, Cousin Magnum, who must have been close to Dubya in age, was Dubya’s first cousin, son of the sister of Dubya’s father. Dubya, of course, remembered neither his father nor his aunt. Ham checked the family tree to see how Magnum had listed Grandpa Dubya’s father. It said simply “R. E. MacPherson.”

“Cousin Magnum, what does the R. E. stand for?” Ham asked, as he did every other time Magnum Fox distributed a genealogical tree.

Magnum looked at Dubya and winked. “Ask your grandfather, Ham.”

Brother Bob gave a short devotional about how wonderful it was to celebrate together a long life well lived. He talked about the parable of the Prodigal Son, not so much about the sin of the Prodigal or even his repentance, but more about the party the father gave the son. And how much God wants to give a party for any and all of us. Then he smiled at Dubya and Cornelia, threw open his arms to those gathered there and whispered, “Don’t miss the party!”

A much smaller group gathered at Dubya and Cornelia’s house for cake after the dinner. As planned, Ham drove home. Carl could be heard snoring in the back of the hearse, even through the tinted glass. When they pulled in the driveway and up to the front of the house, they could see through the front window that people were already gathering in the dining room. Dubya looked at Cornelia and said, “What’s he doin’ here?” Cornelia looked up to see her younger brother, Roosevelt Brookshire, looking out the front window at them.

“He’s my brother, Dubya. I had to invite him. But I promise I had no idea he would come.”

Dubya didn’t dislike Roosevelt. But he knew that “Rose” and Thom Jeff despised each other. The conflict was mostly over the fact John Jr., Rose’s older brother, had refused to let Rose join Dubya and himself in the sawmill business, despite the fact Dubya had made it clear he was happy to have Rose as part of the business. That, of course, meant Rose was cut out of the furniture business deal that later proved so lucrative to John Jr. Rose couldn’t be mad at his brother because John Jr. had hired Rose to work in the furniture company. And he couldn’t really be mad at Dubya because Dubya hadn’t opposed him working with them at the sawmill; furthermore, Dubya had benefitted even less from Brookshire Furniture than Rose had. So for whatever reason, Rose’s wrath had landed on Thom Jeff. And being no wilting flower, Thom Jeff had reciprocated the dislike word for word and action for action.

That night it looked like they might make it through the cake and ice cream and go home in peace. Thom Jeff and Rose, both inebriated, had managed to stay on opposite sides of the room. But in the blink of an eye, which is often the case in these kind of squabbles, Thom Jeff and Rose were standing toe to toe yelling at each other at the top of their lungs. Ham had no idea what they were arguing about, and later neither did the two of them. Thom Jeff was poking Rose in the chest with his finger, when all of a sudden Rose produced a pistol and began waving it around the room.

“What the hell are you doin’, Rose!?!” Thom Jeff shouted and lunged for the gun. They struggled, and the gun went off and the front window of the dining room exploded. Everybody froze.

An eternity later, a disheveled and disoriented Uncle Carl threw open the front door and surveyed the room, inhaler in hand. He saw the gun still in Rose’s hand.

“Godammit, Rose. You shot Mr. Ed!”

“Dear Jesus! Who’s Mr. Ed?” asked Edith before she passed out and crumpled to the floor. Aunt Edith always did have a flair for the dramatic.

As he rushed over to relieve Uncle Rose of his weapon Ham had two thoughts. First, the Curse of MacPherson stupidity had been narrowly avoided this time. And second, this probably wasn’t the kind of party Brother Bob or God had in mind.