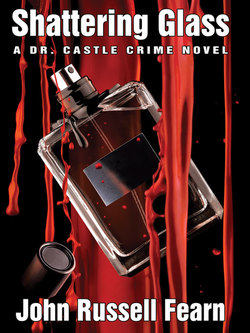

Читать книгу Shattering Glass - John Russell Fearn - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

SNATCH-AND-GRAB

Six years of war, and two decades of rebuilding and redevelopment, might have changed the face of London, but it had not changed the Bachelors’ club. It was still as austere as it had been in l939—gray-fronted, stone-pillared, its heavy oak doors surmounted by the Gothic archway, which is the delight of the antiquarian and the despair of the modernist. It lay to the rear of what once had been prosperous residences and which now were nothing but rubble heaps—a squat, invincible building looming with a certain air of aloof complacency amidst a spider’s web of alleys, small jewelers’ shops, second-hand dealers and light industries. The glory that had been was no more; this disgusting element of commercialism had crept in and around the Bachelors’ club, a product of the post-war era.

“Once,” Perry Lonsdale said pensively, “I was actually content with all this—proud to consider myself a member of this august community. Surprising sometimes how one’s views can change, isn’t it?”

“I presume, sir,” the bartender said as he saw Perry Lonsdale looking with sour interest at the distant vision of gray and bald heads over the backs of chairs, “you find it a bit—slow?”

“Slow!” Perry laughed shortly. “Man alive, it’s dead and doesn’t know it! I can’t think how I ever came to join as a member. Even less can I imagine why I was once perfectly satisfied with it all.”

Perry Lonsdale was tall and narrow when seen sideways, yet when seen from the front or back he was broad across the shoulders. Fair hair lay firmly brushed so as to accentuate a surprisingly high left temple, of which he was secretly extremely proud. The fingers holding the whiskey glass were sensitive; the sharp-featured face was smiling somewhat wryly. It was the expression of a man suffering from intense uncertainty engaged in the relentless struggle of trying to adjust his mind from the hectic life of a pilot to that of a very moneyed but diabolically lonely civvy street.

“I had the time of my life in the R.A.F.” he said, smiling half to himself. “I’ve tried everything I can think of to squeeze a bit of juice out of life and all I’ve got is the pip. As for this place....”

He shook his head finished the drink and stood regarding the glass in his hand.

“How long have you been back in civvy street, sir?” the bartender inquired, folding a napkin swiftly and laying it neatly on one side.

“Six weeks. Long enough to realize that I’m sorry I left.”

“One thing has not changed....” The bartender was solemn and profoundly sure of himself. “I mean women. A woman might buck you up, sir.”

Perry Lonsdale grinned widely. “I know girls by the truckload and they bore me completely....” He sighed and shook his head again. “No, I shall have to go abroad or something. Or I might even consider joining the Foreign Legion. Whatever happens, you won’t see me in here again in a hurry, unless it’s to be embalmed. I’ve got to do something—anything.”

Trailing vague conjectures behind him like a garment, Perry Lonsdale went across to the check clerk, took his hat and coat and donned them slowly because there was no conceivable reason why he should hurry. Nobody was waiting for him; nobody cared what in blazes he did. Finally, with a liberal tip and a languid nod, he stepped beyond the oak doors into the dark reek of the London night.

Suddenly the blur of sounds that made up this moment of 10:30 in London’s nightlife was shattered by one savage and unmistakable noise—shattering glass. Perry Lonsdale turned his head sharply and finished buttoning his overcoat. The noise had come from somewhere on his left, somewhere in that dark, tangled jungle of second-hand dealers, jewelers and light industrial factories—all of which were closed.

A car appeared, moving at high speed. Its headlights blazed with a bewildering brilliance down a side street. They swung, rounded a corner, and shone full upon Perry Lonsdale for a moment, and vanished as the big car roared away into the night.

Footfalls—suddenly. Swift, pattering, emphatic, coming nearer and nearer, running, filling the wide, deserted street with echo and re-echo. Perry Lonsdale finished his descent of the three steps of the Bachelors’ club entrance and looked at the slender figure of the woman hurrying toward him. She was leaning slightly to one side, weighted down by a large suitcase. She glanced backwards and bumped clean into Perry.

“Oh!”

“Sorry,” Perry said, raising his hat. “Very sorry. I hope I didn’t hurt you?”

“No—no, of course you didn’t. I’m all right.... I suppose it was my own fault, really. Silly of me not to look where I was going.”

The girl turned to move on, but hesitated as the shrill blast of a constable’s whistle smote the air.

“In trouble?” Perry asked quietly.

“No.” But the girl was breathing hard and it did not seem to be entirely from the exertion of running. “You see, I—”

She did not finish her sentence. The gleaming cape of a constable loomed out of the night and a powerful torch blazed inquisitively. Perry Lonsdale glared.

“Confound it, officer, is your sight bad or what?” he inquired. “Can’t you see me—or rather us?”

“Sorry, sir.” The voice was gruff and the light was extinguished. “Maybe you can help me.... Seen anything of a smash-and-grab party round here tonight?”

The girl put down her heavy suitcase and the eyes of both the constable and Perry strayed to it. Then Perry looked up again.

“I did hear glass being smashed,” he confessed. “Then I saw a big black closed car moving as though it were trying to beat the world’s speed record. Came right past me on the road here and seemed to come from one of those alleys.”

“And you, miss?”

“I saw an attempted smash-and-grab.” The girl spoke without hesitation and seemed in full possession of her wits. “In the lamplight I could see three men in that car. One threw a brick or some sort of object as he jumped out of the car. Another man followed him. They dived for the window they’d broken. Then when they saw me watching they just made a hasty grab at the brick again, dived back to the car and drove off. I—I sort of got scared and started running—until I collided with this gentleman.”

“Perry Lonsdale,” Perry murmured, raising his hat again. “Good evening.”

“I’m Moira Trent.”

Two more gleaming capes and helmets appeared from the distance. A squad car with its purple police sign on the roof, pulled up at the curb.

“Well, Miss Trent, that’s all very interesting,” the constable said, finally, and it became apparent that amidst the folds of his cape he had been making notes under the lamplight. “I’d like you—and you too, sir—to come along to the station and sign a statement. It will help us a lot.”

“Glad to,” Perry conceded, and after a brief pause Moira Trent nodded.

The officer opened the rear door of the car. Perry heaved in the suitcases, then the girl and he settled themselves in the leather upholstery. The girl, Perry noticed, kept her hand on the suitcase.

“Nothing like the unexpected to brighten life up a bit,” he commented genially.

“That,” Moira Trent said, “is what I don’t like. I prefer things ordered and planned. Things that happen unexpectedly upset everything. It’s like drying your face on a wet towel when you expect to find a warm one.”

The car pulled up in front of the station. Perry helped the girl out; then, seizing her case, he tugged it into the bare, barrack-like building.

“This won’t take a moment,” the constable said. “I’ll just type out your statements and then you can sign them.”

The typewriter began clicking. Perry shifted his gaze a trifle and found Moira Trent looking at him.

“Not very talkative, are you?” Perry asked genially.

She gave a brief, troubled smile and glanced about her. Then she sighed. “It’s this place. A police station is no place to talk. Doesn’t give you any inspiration.”

Finally the clicking of the typewriter ceased and the constable walked forward with two separate statements in duplicate and laid them on the counter.

“This is what each of you said,” he explained. “If you’ll just sign ’em and put your addresses....” He took a pen from the rack and held it for the girl. She took it and wrote “Moira Trent” with as many curves as a chorine. Perry scribbled his signature.

“That all?” he asked pleasantly.

“Er—not quite. I’d like to know your address, Miss...er...Trent?”

“I haven’t got one yet,” she answered. “I only arrived in London late this evening.”

“But you must be going somewhere?”

“I have a place in mind, certainly, but until I get there and can be sure of a room, I can’t truthfully call it an address, can I?”

“Then where,” the constable asked, “did you come from?”

A fraction’s hesitation, then—“Bristol.”

The red, freckled hand wrote “Bristol” and added in parenthesis—“Of no fixed abode.”

“Confound it,” Perry objected, “you make her sound like a tramp!”

“Sorry, sir, but in the legal sense that’s what she is without an address. And there’s something else, Miss Trent. I’d like to know what you’ve got in that bag....”

“Well, I—”

“I’ll handle this.” Perry interrupted and to the constable he said calmly, “You’re exceeding your duty, officer. We are only witnesses, not suspects.”

“That, sir, I grant. But I am entitled to ask the young lady, and I’m doing it. It’s merely to help. If you refuse, miss,” he told her, “you’ll be quite within your rights—but we can always take the necessary steps to get in touch with you, and the suitcase, should we wish.”

“Don’t do it,” Perry instructed her but she only smiled slightly.

“It doesn’t really matter.” With a quick movement she snapped open the lid. She waved a hand to it and said: “Please don’t embarrass me too much.”

The constable peered into the case. So did Perry. It was filled with lacy feminine trifles and at one end were half a dozen thick books, which evidently accounted for the weight. The constable pushed his hand in the miscellany of garments and stirred them slowly as though he were mixing a pudding. But he didn’t miss a single corner. Then he picked up the books, examined them carefully, dropped them back into the case.

“Mmm—all right,” he said finally and sounded most disappointed.

Perry picked up the suitcase and followed the girl out of the police station. The constable watched them go. Then he picked up the statements and went across to the private office. He knocked on the door and a bass voice responded.

At the desk in the center of the office sat Divisional Inspector Latham and the station inspector, a worried looking individual with thinning hair.

“Reports from the only witness and part-witness, sir,” the constable announced.

The divisional inspector looked at them and sighed.

“When we received your message—” he looked at the constable—“I thought we had a good chance of tracing the Farrish gang. That’s why I took charge personally—but now it seems that I was wrong. The Farrish gang would never let a woman interfere with their plans. They’d have killed her first.”

“Then maybe the woman’s lying sir,” the constable suggested.

“No, she wasn’t lying,” Latham said. “Before I came here I had Millington, the jeweler, visit the store and look over the stock. Nothing had been taken except the object used to smash the window, and that tallies with the girl’s statement. Though why on earth the thieves took the trouble to retrieve the smasher and left thousands of pounds worth of jewelry behind is something I don’t understand. The only damage apart from the window, was two cut-glass rose bowls smashed to bits. It’s queer—infernally queer. “It doesn’t smell like the Farrish crowd to me.”