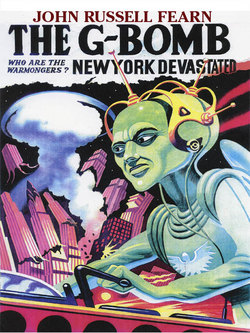

Читать книгу The G-Bomb - John Russell Fearn - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

OTHER EYES WATCHING

The crew of the spaceship that had crossed an interstellar gulf was in conference. Recently revived from their long sleep in suspended animation, they were in orbit a million miles from the Earth. Their craft was hidden from any observers on Earth by reason of a projected image that gave it the appearance of a lifeless chunk of rock, just one of many near-Earth objects drifting in space.

Altogether there was a score of them, big-domed, broad-chested beings, accustomed to an attenuated atmosphere and light gravitation. They had voyaged to Earth from their slowly dying home planet, some 100 light-years distant, guided unerringly by a signal sent from a computer-controlled probe craft that had discovered the Earth more than two hundred and fifty years earlier.

“My friends,” their Leader said quietly, surveying his alien comrades, “we face an unexpected problem. The race inhabiting this planet are much more numerous and scientifically advanced than was originally reported to us by our robot probe. We did not foresee how they could have developed so quickly.”

“Was the probe in error?” one of the crew asked. “Has it malfunctioned?”

“No. On the contrary, it has performed perfectly. Its computer brain has been making observations and recordings ever since it arrived. All of its valuable data has now been transferred to our own ship’s central computer brain. As Leader, I was revived ahead of the rest of you, and I have been analyzing the recorded data. I now know everything about this planet and its peoples, including its main languages—thanks to computer analysis of their radio and television broadcasts. In their main language, English, they call themselves ‘humans’ and their planet is known as ‘Earth’ They measure time in units of what they call ‘years’, this being the period of their revolution around their sun. Our probe arrived here some 250 of their years ago.”

A ripple of unease passed amongst the assembled crew. “They have radio and television? Just how advanced are they?” one of them asked. “When we set out on this mission, they had neither! The data we had said that they were an extremely backward race, without even any mechanized transport! How has this mistake been made?”

“No mistake has been made.” The Leader spoke irritably. “The situation has arisen purely because of the limiting factor of the speed of light. On its arrival here, the probe sent a radio signal back to our home world, stating that Earth was a fair world, with a breathable atmosphere and abundant natural resources—ideal for our race to migrate to. Its backward inhabitants were relatively few in number, of no account scientifically, and could easily be eliminated or enslaved. The radio signal took some 100 Earth years to reach our planet. Immediately it was received, our ship was readied as the vanguard for our invasion, our mission being to prepare the way for our race to migrate here. Naturally, since we cannot travel faster than light, we were obliged to go into suspended animation. Allowing for deceleration, it has taken us another 150 Earth years to arrive, But in that interval—whilst we slept in suspended animation—this Earth race has increased its population astronomically by advances in medical science, and advanced at a phenomenal rate, from animal transport to space travel and an atomic age technology!”

“Space travel!” another ripple of unease amongst the crew. “Are we in danger of detection by Earth vessels?”

“No.” The Leader waved a deprecating tentaculate hand. “They are still at an early stage, and apart from unmanned probes, have not ventured much beyond their dead satellite. Even if their instruments detect our vessel, they will take it to be just space debris—a chunk of rock. They appear to be obsessed with putting observation satellites into close orbit for spying upon themselves—completely unaware that we are spying upon them!”

There was a relaxation of tension amongst the crew.

“Another of their traits is to make visual reconstructions of their own past history, with what they call ‘films’. They also make other rather ridiculous films that are entirely fictional, which apparently they find entertaining. These films are constantly being broadcast, and many of them have been recorded by our probe. Our central computer was able to select and replay to me those that had genuine historical content. It was these that I found to be immensely useful.” The Leader paused and looked at his fellows, saw that he had their complete attention.

“Once,” he resumed, “not too long ago, the Earth people came close to completely destroying themselves in a world-wide conflict. Just when it seemed our ambition would be realised, when they developed the atomic bomb, they ceased fighting! At that very supreme moment when it seemed logical they would annihilate each other, they became peaceful, and, for the time being, our cause was lost. There continue to be numerous localised conflicts, but they result in relatively few deaths—at least, for our purposes.”

There was a murmuring of frustration amongst the assembled crew. The Leader clenched a tentaculate hand on a broad table in front of him.

“Our need, my friends, grows more desperate with the passing years. Our home planet is no longer of service. Its surface has become too arid and its air too thin for us to move far from our underground cities and these cities demand a colossal amount of power for their upkeep, far more than we can really afford. Already our race is hampered in expansion because we have deliberately put a limit on the number of matings and progeny we can allow. Such depletion cannot be stopped unless we have again a world whereon we can live in freedom, a world whose surface is bountiful, where the atmosphere is breathable. For many cycles we have been sending exploratory probes to all sectors of space. At the time we left, only one world had been discovered that fitted the description, and that is the one that is called ‘Earth’ by those who dwell on it. And we were selected to form the vanguard.”

This time the assembled crew merely nodded courteously and then glanced at one another. They did not dare reveal that they were bored, for they certainly were. All this recounting of known facts was tedious. Their chief anxiety was to know what the Leader proposed to do next.

“Our numbers are not sufficient to permit of us invading Earth and conquering it,” the Ruler resumed after a moment. “Our science is superior, certainly, but if we flung ourselves into an all-out war against Earth and tried to invade it we would be bound to tear great gaps in our ranks. The Earth people are not primitive by any means, and they have weapons that could certainly inflict grievous losses upon us. In our depleted condition we cannot afford that risk. Our best strategy lies in making these Earthlings destroy themselves and so leave us an empty planet, or if not that, then one so denuded that our victory over them would prove superlatively easy. To that end, I have been perfecting a plan whilst I waited for the automatic machines to revive you at their appointed time.” He paused, then added triumphantly: “I have chosen a weapon which, produced on Earth, should definitely lead certain factions to precipitate that cataclysm that will pave the way for a successful invasion.”

The assembled crew began to take more interest. Apparently they were arriving at the point they wanted—a method of causing the Earth race to destroy itself.

“I am referring to the Gravity-Bomb. Can you imagine the reaction of certain factions on Earth to a weapon like that? I am convinced that such a device, allied to the knowledge of atomic power that they already possess, will lead them to destroy themselves, and our mission will be accomplished.”

“An excellent conception,” one of the alien crew commented, “but it will call for considerable selection to choose the right people on Earth. No one must ever be suspicious of the other, or the cause will be lost before it begins. They must not have the least idea that they were being manipulated by us.”

“If they did become suspicious what could they do?” the Leader asked, shrugging. “They are scientific up to a point, but they haven’t the least idea that they are being watched by a race of expert scientists who have learned all there is to know of the secrets of radiation and mind-force. They cannot devise a barrier to the mind-emanations we will send forth. Violence amongst them must be fostered to the greatest possible extent. We shall never perpetuate our race to its full glory otherwise. However, come with me now and I will show you those whom I have selected for our plan.”

The Leader rose, and with unhurried dignity, led the way from the chamber, his contemporaries following behind him. They passed down the immaculate, polished corridors of the large vessel, and so finally gained the giant laboratory wherein was housed all the creative genius of the aliens.

At the entrance the Leader glanced behind him at his followers. “Actual hypnosis en masse, I have found, cannot be used. The law of self-preservation, highly developed in Earthlings, prevents them from absorbing hypnotic orders to kill themselves.”

The Leader led the way to a section of the gigantic laboratory where the astronomical observations were being conducted. Although they were a million miles above the surface of the planet the huge X-ray devices incorporated in the reflectors penetrated straight through intervening atmosphere and solids as if it were glass. Nor were the telescopic mirrors anything like those on Earth. They worked magnetically, absorbing light-photons and then amplifying them, with the result that images up to millions of miles away were reproduced with almost their original size upon the receiver screen before which the alien expedition now stood

“First,” the Leader said, touching a button, “I wish you to see the man who, I trust, will become prime mover in our cosmic chess game. He has been intimately studied, his brain analysed, and his hopes and ambitions clarified. Here he is.”

Under the actuation of countless controls the telescopic equipment picked up a solitary point upon the planet Earth, a million miles away, and there appeared on the screen a pin-sharp image of an elderly man, sixty perhaps, poring over a mass of sketches and scientific notes. In appearance he was nondescript with straggly grey hair, a thin face, and small body. In fact, his general attire and the surroundings amidst which he was working conveyed the impression that he was not too well-blessed with the world’s goods.

“His name,” the Leader said, “is Jonas Glebe. To us a peculiar name: to him, as an Earthling, quite normal. He lives in a country called England in a town—or rather a city—called London. He has one daughter, Margaret, who whilst not possessing any of his scientific tendencies, is nevertheless his bosom companion when she is not engaged on a task that occupies her every day. Apparently, as did the members of our civilisation in the long-dead past. Earth people work daily at some particular task, usually one for which they are neither mentally nor physically fitted, and in return they receive money, the balance of which—after dues to the State and other bodies—they are allowed to retain to keep themselves alive. A curious, archaic mode of existence, my friends.”

The aliens watched the elderly man busy with his papers. Presently they saw him fling them aside in disgust and sit pondering.

“On the dial here,” the Leader said, nodding to it, “you see recorded his mental-energy quotient. It is not a high one, but finely balanced. Observe—”

The others looked and saw a delicate electro-magnetic needle hovering around the a reading that was approximately one third of the highest possible mental rating known to their science and rarely reached even by their master-brains.

“Yes, fairly high,” the Leader repeated, “and being finely balanced it will be capable of receiving the mental suggestions we shall project at him. By profession he is a small-time scientist and has made a little money by means of what the Earthlings call ‘gadgets’, but he could certainly do with a good deal more. Now, let us suppose that we plant in his brain the secret of the gravity-bomb. He will claim it as his own idea, of course, and endeavour to market it. Since he will not know where to start we shall have to mentally suggest to him that he deals with this person. Observe him—”

Under the manipulation of the telescopic controls the view of Jonas Glebe faded from view and was gradually replaced by one of a man seated in an opulent office. There were six telephones on his enormous desk and behind him was an immense window giving a view over the dreary roofs of London. The man himself was very square-shouldered with iron-grey hair, closely-cut, sensual lips, and rather prominent eyes. In dress he was immaculate and costly rings glittered on his fat fingers as he thumbed through stacks of documents.

“You are looking at Miles Rutter,” the Leader explained. “I am not sure that is his real name, but in any event he is the second protagonist in our experiment. He is a man of power, tremendous wealth and influence, and under various names controls many enterprises, most of them connected with Earth’s basic necessities like metals, food transport lines, and so forth. He has tremendous ambitions. This man Rutter wants the world, like many before him, and he has every conceivable means of achieving his ambition—except one. He has no scientific weapon powerful enough to set fire to the tinder pile. With the G-Bomb, my friends, we can provide the missing factor.”

“Agreed.”

“There,” the Leader said, switching off, “we have the two main characters. The one with the G-Bomb, and the other with the ruthless ambition necessary to destroy the human race in his effort to dominate it. Nothing could be simpler or, I hope, more certain of success.”

“Who have we on the other side?” one of the expedition asked, as the Leader stood musing amidst the apparatus.

“The other side?”

“Yes. It has always seemed to me that no matter what destroyer a man invents, there is always somebody clever enough to devise a defence. I cannot believe that on this thickly-populated world of Earth there will not be a scientist capable of finding a deterrent to the Gravity-Bomb.”

The Leader smiled. “You are rating the intelligence of these Earth people extremely high, my friend, which is not at all a sensible procedure. Though we have not, of course, gone through the involved task of testing every Earth mind individually we have at least discovered that the vast majority range around one fifth of our abilities. That is extremely poor. Here and there an exception does touch the thirty percent mark. In Jonas Glebe alone have we found a registration of thirty-five.”

“Which means he is the cleverest man on Earth?”

“Potentially, yes, but even the cleverest man cannot prove his power unless he offers something superbly brilliant—and that is what the G-Bomb will seem to be. Have no fear. There is not a man or woman on Earth capable of finding a neutraliser for the G-Bomb. All we have to do is transmit the details of it, and then watch Earth people gradually set about the task of destroying each other.”

The aliens nodded but asked no further questions. As far as they could see there were none to ask. The fact that a pair of men on Earth were going to become pawns in their game that did not concern them in the least. They had long since passed the point where they had any sentiment for living beings, as such. All of them, even their own people, were but units to be handled as science deemed best.

The Leader crossed to a massive apparatus with a keyboard like the manual of an organ. A switch started a pale emerald beam projecting downwards so that it completely enveloped the Ruler’s head. With a gradually deepening dreamy look in his eyes, he sat back, mechanical aids operating the keyboard for him. He concentrated—and the others watched and made no utterance.

* * * *

It was the click of the door latch that made Jonas Glebe glance up quickly. He blinked, surprised to notice how much the gloom of the winter afternoon had closed in. The small living room was cold and full of grey shadows. Against the solitary window with its faded net curtains the rain was battering relentlessly.

“Why, dad, what on earth’s the idea?” Margaret Glebe came into the gloomy room and switched on the light. Her father blinked in the abrupt glare and Margaret, her wet rainproof gleaming, observed him in concern.

“Anything the matter, dad?” She came over to him quickly. “You’re not—not ill or anything?”

“Bless you, dear, no. I was just lost in thought. I sort of forgot everything.”

Margaret gave a little sigh of relief. “Oh well, if that’s all! Y’know, you’re a terrible one to look after yourself. Fire’s not on, and you were sitting in the dark. Next thing we know you’ll be catching bronchitis. Do you realise it’s nearly six o’clock? I got home a little earlier this evening: Mary’s taking the cash-desk for me.”

“Oh— Six o’clock? Is it?” Jonas Glebe stirred stiffly and squinted at the clock on the mantelshelf. “I hadn’t realised. I suppose one doesn’t when thinking.”

“No, dad, I suppose not.” By this time Margaret had pulled off her rainproof and switched the kettle in the adjoining kitchen. She turned to look through the open doorway and said quietly: “I just wish your thinking did you some good, that’s all. You’ve been at it for years, ever since I was a little girl anyway, and I can’t remember how much benefit it brought you beyond a cheque for a gadget maybe.”

Her father was silent, absently studying her. She was good-looking after a fashion—dark, as her mother had been with straight features and a practical chin. She had none of her father’s abstractedness, and certainly none of his inner scientific genius. Her present occupation was that of cashier at a cinema: her ambition, to find a young man who could take a load from her shoulders.

“I suppose I am a bit of a nuisance,” her father sighed, getting to his feet.

“Maybe I should have married earlier then you wouldn’t have such an old father. I’m pretty much in your way, dear, aren’t I?”

“Dad how can you say such a thing!” Margaret kissed him gently, and then gave him a serious look. “You’re never in my way! You’ve misconstrued what I mean. I think you don’t get a just reward for the things you can do. You’re one of the best scientists in the country—in the world in fact—and what happens? They say you’re too old to join a scientific organization—too old at sixty-two—and your best ideas you forget to patent or something, and somebody else nets a fortune on them whilst you get a pittance. It isn’t right, dad. I don’t want to sound as though I’m lecturing you, but you ought to wake up.”

“And do what, my dear?”

“Well—something.” Margaret looked vaguely about her. “Some kind of quiet job perhaps, and do your scientific dabbling in your spare time.”

Jonas Glebe shook his head. “Believe me, Marg, if I took a job it wouldn’t be doing my employer a service, or myself either. I’d be thinking of other things all the time and my paid work would suffer in consequence. No, once you’re a scientist there’s nothing else you can do properly; not when you get to my age, anyhow. I realise that a job might improve our surroundings, but is that so very important. We’re happy, aren’t we?”

“Yes, we’re happy, but—” Margaret fell silent, her eyes on the untidy little living room. Then she glanced towards the doors that led to the two small bedrooms.

“A man doesn’t need anything more than a roof over his head where he can work out his problems,” Jonas Glebe said. “A youngster like you needs much more of course, but you have it. You’re out all day, and in the evening too if you wish. You don’t sec much of this flatlet of ours. If you think it worries me, it doesn’t. A man can have thoughts which blind him to his surroundings.”

The girl went across to the kettle as it clicked off. Busy with her own thoughts she made the tea, and then set out the table. During the process her gaze travelled to the stacks of notes on the little bureau at which her father invariably worked. She had seen notes like that for as long as she could remember and it assaulted her practical mind that nothing ever seemed to come of them.

“Just what line of thought prompted you to sit in the dark with the electric fire switched off?” she asked, when she and her father were seated at the simple tea.

“That? Oh, I had the dim beginnings of an idea, only I’m not sure whether I should go ahead with it. It’s an idea so simple and yet so diabolical I’m almost afraid to speculate further.”

“Simple yet diabolical?” Margaret gave a frown. “How could it be?”

“It’s a bomb,” her father explained simply, buttering a slice of teacake.

“Oh! Don’t you think the world’s had enough of bombs and slaughter without adding more? Anyway, what else can there be in bombs? We’ve already got the atomic bomb and the hydrogen bomb. Don’t tell me you’ve thought of one that’s even more horrible?”

“No. My bomb has nothing to do with a particular explosive: that could be left to the organisation buying the bomb. It’s just an empty case to start with and you can put in it what you like, from plutonium to ordinary gunpowder. Just the same it’s—fiendish.”

Margaret puzzled the business out to herself as her father became momentarily silent, musing to himself. Then he stirred a little as he realised his daughter’s eyes were upon him.

“It’s so tremendously simple,” he said. “I can’t think why it never occurred to me before—or if not to me then to an inventor of armaments somewhere.”

“You’re not being frightfully explicit, dad!”

Jonas Glebe smiled. “Sorry, dear. That’s because I haven’t worked out the details. Not much use me claiming I have something wonderful and starting to explain it until I’m sure, is there?”

“Then you do intend to go ahead with this thing, diabolical or otherwise?”

“I think somehow that I should.” Jonas Glebe looked absently in front of him. “Don’t ask me why: just an impulse. After all, even if the notion is diabolical it doesn’t say the bomb will ever be used, does it? It might become such a deterrent to war that no one will ever start one again. That would be quite an achievement! That I, Jonas Glebe, should be the man who stopped war.”

Margaret shook her head slowly. “You’re a dreamer, dad, plain and simple. Neither you nor anybody else will ever stop war as long as there are human beings. There’ll always be somebody trying to be top dog. If I were you I’d forget all about the idea, and invent something simple—like an automatic teapot which brews and pours itself for instance.”

Jonas Glebe only smiled. He did not comment. The far-away look was back in his eyes and Margaret knew what that meant. She gave up the argument and turned her attention to finishing her tea. After it was over she cleared away, and then departed to her bedroom. Half-an-hour later she reappeared to find her father seated by the fire, figuring industriously.

“Don’t mind if I go out, dad?” she asked. “I’ve a date with Ted Jackson.”

“By all means!” Her father did not even glance up. He waved an assenting hand and kept his eyes on his calculations. So Margaret departed and, as the evening advanced gradually forgot her scientific father’s preoccupation with obscure problems. It looked, when she came home towards eleven, as though he had hardly moved position.

“Ted didn’t turn up,” she announced in disgust drawing off her gloves. “That’s the last date he’ll make with me!”

“I’ve got it, Marg,” her father interrupted. “Taken me most of the evening to plan it out, but there’s little doubt that it will work. I think I’ll call it the G-Bomb, partly to honour the first letter of our surname and partly because gravity is its motivating force.”

“Uh-huh,” Margaret acknowledged, again switching the kettle on, seemingly a routine operation, and then removing her coat. She found it difficult to think of bombs when Ted Jackson had failed to keep his date.

“It’s quite unique,” her father added, looking up from his pile of sketches and notes. “Want to hear about it?”

“Yes, but, do you think I’d understand it? I haven’t a scientific bone in my body, as you’ve so often said!”

“You’ll understand this, in non-scientific language. You realise, for a start, that one solid blocks another? That is, you can realise that you don’t fall through the floor because the floor is a stronger solid than you are?”

“That’s plain enough.” Margaret sat down in the battered armchair by the fire and looked absently into the glowing bars. She saw Ted Jackson dancing there. When the image of Ted Jackson had danced into a red haze she became conscious of the click of the kettle and her father’s words. “...so of course, with the electronic poles altered the bomb passes through the solid, and there we are.”

“Yes.” Margaret looked at him rather blankly. “Yes, dad, I see—I think. Excuse me, the kettle—”

“You haven’t heard a word I’ve been saying,” her father said; then he smiled. “Never mind, I hardly expected it. At your age science doesn’t mean a thing to a girl, and romance comes in an easy first, but for your own sake I should try and do better than Ted Jackson. As to myself,” he went on, musing as Margaret filled the teapot, “I’m wondering how much money we can rake up.”

“Money!” Margaret nearly dropped the kettle. “For what?”

“The G-Bomb, of course. It won’t be any use me just submitting a sketch to an interested party. He’ll want to see what a model can do, so I must make one. It will cost me a few thousand pounds.”

Margaret had finished laying the supper before she passed a comment, during which time her father had been putting the finishing touches to one of the many curious designs he had made.

“We might as well try and rake up a few million, dad,” she said flatly. “It just can’t be done.”

“But it must!” Her father glanced up, full of surprise that his wish couldn’t be instantly granted. “This has got to be completed.”

“Yes dad, I daresay—and you’re an old darling—but I do feel bound to tell you that up till now your inventions have cost us several thousand pounds with a total net return of something like half your expenditure! That’s bad business in any language. We could well do that lost money. We wouldn’t be in this dump if we had it.”

“So you’re itching for a fine home and fine clothes?” her father smiled.

“I can’t help thinking that with your ability we ought to have them, yes. Possibly Ted Jackson’s let me down because we don’t amount to much.”

“Then if that’s his angle he’s better left alone. Now, about the money I need. I must find it somewhere. Any ideas?”

“None.” Margaret pulled up her chair to the table. “People willing to give you thousands for a scientific invention only exist in fairy tales. Certainly I have no friends who’d spring it.”

“Then I must see a moneylender,” Jonas Glebe decided, coming over to settle at his supper. “Once I’ve shown a model to the right party I’ll not only collect my outlay and the interest, but thousands upon thousands on top of that! This, my dear, is really going to make us wealthy.”

Margaret did not appear very convinced. She had heard that promise before concerning ‘gadgets’ that had never made beyond a few pounds.

“Dad,” she said seriously, gripping his hand across the table, “why can’t you come down to earth for a moment? If you have a marvellous bomb there, all you have to do is submit the sketch to the War Office and have their experts look it over. They won’t steal it. If it’s worth anything you’ll get all the money you need for research.”

“No.” Her father shook his head. “I’m not at all convinced that the War Office would be interested. This bomb of mine has other uses besides warfare. It can be invaluable in mining, demolition, and similar projects. It could even be timed for use as a fog-signal! In any case I’ve already made up my mind who I’ll contact.”

“Well?”

“Miles Rutter. He’s one of our biggest industrial men and controls all manner of corporations and organisations. If I can sell to him I’ll make all the money I need.”

Margaret sighed. “Very well: but I do wish you’d not talk so glibly about going to a money-lender. Heaven knows where we’ll end if you do.”

“We’ll come out on top,” her father smiled, obsessed—as he usually was at the climax of an inventive session—with complete optimism. “I’ll fix things in the morning.”

Apparently he did, too, for when Margaret arrived home the following evening she found the small living room had been converted into something resembling a workshop. Apparatus lay in all directions and the table was littered with pieces of metal, springs, wires, and a collection of obviously new tools. Her father was busy at the bureau, using it now as a not too satisfactory bench. From the gleam in his tired eyes he appeared supremely happy.

“Hello, dear!” He barely glanced up. “Fix the tea, will you? I haven’t had time.”

Margaret went to work as instructed, asking a question meanwhile. “You got the money, then?”

“Yes—from a moneylender. I traded in some insurance policies as security. None of which matters to me. This model must be completed—and it will take me about a month to do it. I should have an excellent chance of selling just at present with the international situation being so unsettled—”