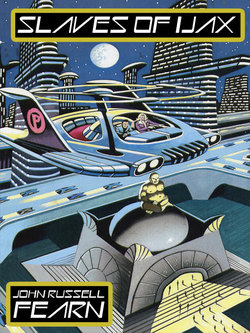

Читать книгу Slaves of Ijax - John Russell Fearn - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

MOONDUST

It was noon when Alza settled the flyer in the lower levels of the city, parking it in a public airport.

“You are sure you wish to take the risk of the people seeing you?” she asked Peter, as she switched on the motor.

“How are they to know the difference? I’m dressed the same as any other man as far as I can see.”

“Except for that.” Alza nodded to a curious pentagon design on his sleeve. He looked at it in surprise, noticing it for the first time. “It represents the highest rank in the world,” the girl explained.

Peter grinned, pulling the loose sleeve round so that the outside was nearly inside between his arm and body.

“That settles that!” he said. “If anybody asks, I’ve got a stiff arm or something. Now let’s go.”

Alza looked at him curiously then she climbed out of the cabin and he followed her. He gazed round the airport and upon the gigantic buildings looming far above them on every side.

“There’s an automat a little distance off,” Alza said. “If you will follow me, Excel... I mean Peter?”

“I’m not going to follow you; I’ll walk with you. Believe it or not I find your company most enjoyable.”

“I’m glad,” the girl murmured. “I try to be helpful.”

Side by side they walked along the pedestrian way, passing by men and women who gave them no more than a glance. Peter could see no difference in the types despite the passage of seven centuries. There were tall ones and short ones, dark and fair, fat and thin, the only difference being that every one walked with complete erectness and in the bloom of health. There was no stooped shoulders, no signs of consumption, no maimed. The one thing Peter did not like was the identical clothing worn by both men and women—ankle length robes for the men and knee length for the women. At a distance he would never have been able to distinguish Alza Holmes from a million other young women. Gone completely was individuality....

Within the automat Peter naturally expected to find tables—or al least a long self-service counter. To his surprise everybody was reclining full length on air beds, stretched out in lazy comfort and tended by robots moving to and fro across a waste of shining floor.

“There are two beds over there,” Alza said, nodding.

She led the way and reclined with easy grace on the first one while Peter lay down on the second—though scarcely with easy grace. The idea was new to him.

“I shan’t be able to eat lying down,” he protested.

The girl turned her head to look at him. “Yes you will, Peter. You’ll see.”

He did. Service was prompt, Robots arrived and operated something under the beds which tilted the head-end up, and following Alza’s example of complete ease, even to closing of the eyes, Peter allowed himself to be fed with gentle, silvery metal hands. Which in fifteen minutes gave him a meal as perfect as the one he had had in his suite. A kind of wine followed, then the beds were lowered again and he and the girl lay flat once more.

“One certainly does oneself proud in the Twenty-Eighth Century,” Peter murmured dreamily.

“We have learned, Peter, to rest our minds and bodies completely in those periods when no action is called for,” the girl answered.

“Did you pay for our meal?” he asked.

“No. Meals are provided by the State. It will seem a startling innovation to you, but we found out long ago that the root cause of trouble is usually hunger, so the Federation decided that meals for all should be a State concern. It makes things a lot easier.”

“Are you telling me?” Peter exclaimed. “The politicians of my time would go bald at the mere suggestion. But what about money? Don’t you earn a salary as a secretary, for instance?”

“No, It is my chosen vocation. I do it because I like it. Money too was found to be the cause of all wars and economic crises and so was abolished when the new order was formed. Everything now is done by barter.”

Peter became silent, lying perfectly at peace. For a few moments he studied, man-like, the lissome curves of the girl stretched so near to him, her eyes closed, head pillowed on her arm—then he looked beyond her to the other men and women lying down as far as he could see across the great room. Gradually one impression rooted itself in his mind. They all looked the same! Not in appearance, but in expression. He was accustomed to seeing happy faces, moody faces, exasperating faces even—but here there was one expression shared by all alike, except perhaps Alza; a dreamlike look, a vacancy, as though thoughts were far away from the immediate surroundings.

In fact it struck Peter so strongly he had to speak about it.

“It is probably because most people have so little else to think about outside the Task,” Alza said finally. “Everything else is done for them, you see. You do notice it among the great mass of the people, but among the intelligentsia, the circle in which you and I move, there is more individuality.”

“Moonstruck,” Peter muttered. “That’s how I’d describe them. And that reminds me! Moondust! Wish I could think what it means. I’ve heard all about it somewhere, once.”

Alza remained looking at him, her face sideways, a faint smile on her full mouth. Then another question popped into Peter’s mind.

“I suppose there’s no crime?”

“Not any more.”

“There has been, then?” Peter asked.

“Up to five years ago,” Alza replied. “At that time the last great criminal on Earth was brought to justice—one Anton Shaw. I suppose he was about the cleverest and most malignant scientists in history. He did his best to rule the world, anyway. With his departure society resumed its usual crimeless state and has been like that ever since.”

“What happened to him? Was he executed—assuming you still have the death penalty, that is?”

“No, but he was exiled, as far as I remember. I didn’t really pay any great attention at the time.”

“Well, it doesn’t sound to me like a sure way of suppressing a criminal scientist.” Peter sighed; then for a long while he relaxed again, the persistent memory of moondust trying to struggle into his consciousness.

“What’s your impression of Mark Lanning?” the girl asked him after a while.

“Lanning?” Peter stirred lazily. “A bit strange—decent enough under his icy cloak, I suppose. You’ve known him longer than I; what do you think?”

“I just don’t know,” Alza mused. “I first met him seven years ago when I became a secretary. At that time he was friendly to everybody, then after he met with his accident all his good nature seemed to evaporate and he became the impersonal creature he is now. I’ve often wondered if the operation he underwent didn’t change him somehow.”

“Operation?” Peter opened his eyes inquiringly to find the girl looking at him.

“He was injured in the head by a laboratory accident and had to be operated upon,” she explained. “As a matter of fact it was Anton Shaw himself who performed the operation, some little time before the law caught up with him. At that time, being the head scientist, he was also a master-surgeon. He put Mr. Lanning on his feet again, anyway, and except for his change of manner he’s been healthy enough ever since.”

Peter reflected for a moment. “Did Anton Shaw know at that time that he was heading for a fall?”

“He might have had hints, but he couldn’t have known. I think Lanning had a really painful task in arresting Shaw, for it was he who found out the unsavoury truth. It has always seemed to me that he felt it keenly—having to turn over to justice the very man who had saved his life.”

“Mmmm...,” Peter mused. “I just wondered. Had Shaw known what was coming he might have done something to Lanning as a sort of advance revenge.”

The girl shook her head as though she doubted the possibility; then Peter sat up actively and gathered in his robe sleeve with its insignia.

“I think we ought lo be on the move, Alza. This lying down may be a good idea but I’m more accustomed to exercise. Coming?”

The girl rose and stood up, question in her grey eyes. “Where would you like to go now, Excel...Peter?”

“Well, I’ve been thinking.” He took her arm deliberately as they left the place and felt pleased by the fact that she did not resist his action. “Have you anywhere in this city where you keep information? I mean a sort of reference library, or a place where records are kept?”

“We have the Historian’s Hall, about a mile from here. What are you seeking, exactly?”

“Moondust,” Peter said, with an amiable grin. “I want to find out about it. I know I’ve heard of it somewhere.”

Alza nodded and they continued walking down the street. Peter had the impression that exercise did not appeal to the girl, for she kept glancing wistfully towards the floating air-taxis. But since he did not give word to summon one she obviously could not. In five minutes they reached a corner of the pedestrian level and the girl pointed over a bridge spanning the nearest canyon of street to a building with a door at pedestrian street level.

“That’s it,” she said. “Quite an interesting place....”

They crossed the bridge and entered a wide hall of many windows admitting the afternoon sunshine. There was nobody in sight and the emptiness echoed with their footfalls as they crossed the richly tiled floor to a door in the distance. Beyond it they entered a room of breathtaking dimensions—and for a moment Peter found himself gazing about in awestruck wonder.

As the girl directed him towards the reference library his pace slowed. He just could not get over the fascination of the exhibit cases. There was a wry smile on his face as he looked at a genuine antique automobile of 2050. Then there were parts of a hydrogen bomb, described as man’s most devastating weapon in the twenty-first century. Had he not had another purpose in mind he could have lingered for the rest of the day over such offerings.

He entered the reference library to find that the girl had already summoned a robot, which was placing a truly colossal book of fine metal leaves on a desk. It was a giant encyclopedia covering every conceivable thing in the world from A to Z. Rubbing his hands gently together Peter sat down in front of it and the girl stood watching over his shoulder.

“M for moondust,” he murmured, turning the pages and marvelling at the clearness of the coloured illustrations, “Moon. Moonbeam—Moonblind—Moon-daisy— Ah. moondust! Here it is!”

Alza followed his finger to a thick paragraph of type—

Moondust—a mineral allied to quartz, silica, and silicon dioxide, crystallizing hexagonally after the fashion of quartz. According to Webster and other prominent scientists it is unique in that it is photogenic to the action of moonlight, revealing a definite energy-excitement when stimulated by the rays of the full moon. In sunshine it lies dormant. Moondust possesses much of the capacity for varying electrical resistance in light and dark as does selenium.

“So that’s what it is!” Alza exclaimed, mildly surprised. “I never bothered to find out.”

Peter closed the book slowly. “I remembered my friend Michael Blane referring to it once. The name of ‘Moondust’ has such a lyrical sound I couldn’t easily forget it.”

“I wonder,” Alza mused, “why the Task demands that we should fill the Grand Tower hemisphere with moondust? It’s—peculiar.”

“It’s not the only thing which is peculiar,” Peter responded. “Why all the channels from the Grand Tower? Why a Grand Tower at all, if it comes to that? There’s a whole heap of things in this age that I don’t understand, Alza, but since circumstances have made me the figurehead, I mean to find things out. The trouble is I’m not a good scientist. How about you?

“I’ll do my best to explain anything scientific that puzzles you,” she responded.

“Good!” Peter got to his feet with a grin. “Let’s start with moondust itself. Is it being mined somewhere in readiness for the Tower, or what?”

“I believe it has been mined for the past two years. As I told you, that’s Mr. Lanning’s chief concern.”

“Well, I’m no wiser,” Peter sighed, tugging at his underlip. “All right. Let’s kill a little more time by taking a look at the museum. It may bore you but it’s fascinating to me. The stuff you class as ancient I’ve never even seen.”

She followed him back into the exhibition hall, and apart from the ‘ancient relics’ there were other scientific marvels that fascinated him. Chief among them, out of date though it was, was an automatic Eclipse-Forecaster that after the touch of a button went through mystic inner calculations and finally revealed the date in a small display, underneath the word ‘Sun’ or ‘Moon’.

After checking back on eclipses he had seen during his lifetime, he felt assured of the instrument’s accuracy and cast ahead in time yet to come. For 2746 one solar eclipse, partial, was due on the 8th November, and one total lunar one on September 28th.

“Pretty good,” he said at last, wagging his head admiringly. “Could have done with something like this in my day. Incidentally,” he added in surprise, “what’s the date today? And the month?”

“It’s the thirty-first of July, Twenty-Seven Forty-Six,” the girl responded. “And, Peter, I think its time we had some refreshment. We have been in here over four hours.”

“Time flies when you’re interested,” Peter apologized, smiling. “All right. And thanks for waiting for me. I’ll bet you’ve been bored—I used to be with museums at home.”