Читать книгу The Gold of Akada: A Jungle Adventure Novel - John Russell Fearn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

THE WHITE GIANT

1932

The air was quivering with both the tropical heat of Central Africa and the reverberations of the drums. Drums, echoing through the primeval forest, their exact situation undetectable to the white man who sat flung in his rattan chair, his hand gripping the half-filled glass on the okume-wood table before him.

“Blasted natives,” he whispered. “And out to get us, Ruth. They’ve been trying it ever since we struck this part of the jungle.”

The young woman addressed did not answer. She was half afraid to. As the wife of Mark Hardnell, she was little better than a target for insults and abuse. She sat half-crouched on an upturned crate in a corner of the tent, her dark hair damply untidy on her forehead, her blue eyes darting about her in frightened wonder as the message of the distant drums continued.

Suddenly Mark swung on her, twisting round in his chair. He was a big, powerful man in the early thirties. Even in normal circumstances he was not a pleasant man, overridden as he was by ambition—and just at present he was unbearable.

“For God’s sake, Ruth, stop those kids bleating!” he yelled at her. “We don’t want to give away our position. And put out that damned lamp!”

Ruth began moving, extinguished the oil lamp, and then in the almost total blackness she stooped over the roughly crib in which two infants wailed lustily. They quieted a little under their mother’s touch.

“You would have twins!” Mark’s sour voice came out of the clinging, stifling murk. “It would have been bad enough to have one kid on a trip like this, but you had to have two! Damnit, you knew back in Zanzibar what was going to happen. Why couldn’t you have stayed there until the thing was over?”

“My place is with you, Mark,” Ruth said quietly.

“Don’t hand me that! You hate the living sight of me!”

“I’m still your wife, Mark, and prepared to live up to it. If I hadn’t come out on this ghastly trip, you’d never have ceased to curse me when you got back to civilization. Whatever I do is wrong: I’ve grown accustomed to it!”

“Oh, stop yelping!”

“I’m entitled to,” Ruth continued, her voice low but quite steady. “We wouldn’t be here at all, lost in the jungle, but for your crazy idea of trying to find a lost city. Ivory, jewels, gold—!” Ruth laughed half hysterically. “That was what you said—”

“I was right!” Mark blazed at her. “I’ve got the plan, and I trust the man who gave it to me. There is a city in this region somewhere. The hard part is finding your way, and these damned Bushongo boys are no help, either. Wonder what the devil M’Tani is doing all this time?”

He blundered across the grey darkness to the tent flap and looked outside. There did not appear to be any sign of the carrier boys in the little clearing. There was only the deep tropical night and the eternal message of the drums. Mark swore, then regardless of giving away his position, he yelled harshly:

“M’Tani! M’Tani!”

Something the colour of polished coal tar glided out of the darkness. The only things visible about the head boy were the whites of his eyes and his gleaming teeth.

“Where have you been?” Mark demanded, using the mongrel language M’Tani understood. “Where are the rest of the boys?”

“Gone, bwana. Umango tribe close.”

“Gone, eh?” Mark spat. “Ratted on us, you mean?”

M’Tani did not understand. He was glancing fearfully around him. Only his loyalty to the white boss made him stay at all.

“I told you to discover what chance we had of escape,” Mark reminded him. “Have you done that?”

“Yes, bwana. No chance. Umango much nearer.”

“No chance?” Mark’s eyes narrowed as he looked into the dark. “You mean this tribe is closing in, in a circle?”

The Bushongo nodded urgently, and seemed to be making up his mind whether or not to run for it. Abruptly he reached a decision, swung around, and then fled across the clearing like a shadow.

“Come back here, you scum!” Mark roared after him, then as the noise of drums suddenly stopped, he too became quiet, gazing fearfully around him. The silence seemed awe-inspiring after the reverberation that had been so ceaseless.

Slowly Mark turned back into the tent. He collided with Ruth in the darkness.

“Get the kids,” he said briefly. “We’re getting out.”

“But—where to? Where do we go?” There was utter hopelessness in Ruth’s voice.

“I don’t know. The Umango are all around us, closing in. We might escape. Be better out in the open fighting it out than hemmed in this clearing. You take the kids, and I’ll carry what I can.”

Mark picked up his .303 Enfield and strapped on cartridge bandoliers. Ruth did not go immediately to the twin sons, now silent in the corner; she moved instead to the bottled water, bully beef tins, and other provisions. In the darkness she began sorting them out.

“Why should the Umango particularly wish to attack us?” she asked after a moment. “We’re doing them no harm.”

“We’re in their territory and not welcome,” Mark’s clipped voice retorted. “Our boys have all gone and left us to it. If we’re caught, I don’t know what will happen. Maybe a sacrifice, maybe anything. Come on, Ruth, how in hell much longer?”

“Ready, ready,” she said quickly, putting two water bottles in the big haversack along with the provisions.

Mark lifted the tent flap, peering cautiously into the utter and eerie silence. Untrained in jungle lore, he did not hear the stealthy advance of hundreds of fantastically painted warriors. His first awareness of anything was when a barbed shaft, soaked in venom, crashed into his chest.

He gulped, uttered a strangling cry, then pitched over on his face. Ruth looked up in alarm from the rough crib from which she had been about to gather the infants.

“Mark!” she whispered; then in a sudden frenzy as she dashed to the tent opening: “Mark! Mark—!”

She stopped, seeing him lying face down in the rank grass. In the deep gloom she could detect that he was not moving.

“Mark—” She caught at his shoulders desperately and dragged on them—then another sound made her look up. The clearing seemed to be alive with shadows, sweeping in towards her.

Fantastic figures poured out of the dark. Powerful hands seized her hair, her shoulders, her arms, her legs. She screamed frantically, again and again, until the forest seemed to be echoing to her cries.

* * * *

1952

Caleb Moon sat and sweated. There was not much else he could do in this stinking, tobacco-smoked café on the waterfront of Makondo in Somaliland. As he sat he drank and sweated some more. He was a heavily built man, inclined to corpulence, and dressed in a faded khaki-drill suit. A sun-helmet was pushed up on his damp black hair, His face was podgy, greasy, and unprepossessing. Dark eyes, black as sloes, darted about in eternally restless movement as though he were afraid of seeing somebody he did not like. In a sense this was true. As a trader of dubious scruples, dealing in ivory, diamonds, skins, or anything else that had a value, he had many enemies.

For nearly half an hour he remained slouched, hardly moving, watching either the men and women around him, or else the bead curtains that screened the outer door of the café. Then, suddenly, he straightened and got to his feet. A man and a woman, obviously Europeans, had just appeared and were looking about them. They looked surprisingly clean and cool in this oppressive den of seamen, half-breeds, and drifting women.

Moon went over to the man and woman and raised his sun-helmet briefly.

“Mr. and Mrs. Perrivale?” he enquired, with an unctuous smile. “Caleb Moon....”

“How are you, Mr. Moon?” Harry Perrivale’s greeting was completely matter-of-fact as he shook the trader’s damp hand.

“How do you do?” Rita Perrivale acknowledged, contented with a mere nod.

“Over here—” Moon motioned. “I have a quiet table.”

He led the way to where he had been seated and dragged up chairs. There were one or two curious glances towards the well-dressed Europeans, then interest in them expired. It was too hot to be interested in anybody.

“Drink?” Moon asked, mopping his neck.

“Whiskey,” Harvey Perrivale answered, and Rita named a soft drink. The waiter obliged, and then Moon sat back and breathed heavily.

“I was beginning to fear you weren’t coming,” he commented. “And that would have been a pity—for both of us.”

“We were delayed.” Perrivale sipped his drink. He was a man of thirty-five, sharp-featured, dark, handsome after a fashion, but spoilt by a dissolute mouth and poor chin. “From Port Durnford to here is quite a distance. Anyway, let’s hear more of this proposition of yours.”

“It is unchanged from when I explained it to you in Port Durnford,” Moon shrugged. “I have a map showing a route through Central Africa to a lost city by the name of Akada. In that city there is gold and ivory for the picking up—but I am not a man of money. To fit out a safari to cross Central Africa takes a good deal of finance. You have backed tropical expeditions before now; I thought you might wish to back this one.”

“Mmmm. I gathered that was it. What is there in it for me?”

“Fifty-fifty on whatever Akada contains. Surely that’s fair enough? I have the map; you have the money. Neither of us can do without the other. Share profits.”

There was silence for a moment. Rita Perrivale’s grey eyes travelled over the assembled men and women at the tables and her sensitive nostrils twitched in disgust. She was a girl of infinite refinement, ten years younger than her husband, and not all sure what had been the matter with her when she had fallen for him. He was a millionaire, certainly, but that was not everything.

“Let me see the map,” Perrivale ordered at length, but Moon shook his head and grinned.

“Wouldn’t be good business, sir. You might have a photographic mind.”

“What the hell do you mean?”

“I mean—bluntly—that I won’t show it you unless we have an agreement. Your finance—my map.”

Rita sat back and smiled rather bitterly. She was accustomed to these wrangles with traders and shysters on this torrid coast. Her husband, bored with millions, found he got a kick out of trying to add to them—hence he was known as the moneybags behind most of the expeditions into the interior. Usually he cleaned up something out of his risk.

“I don’t see why you hesitate,” Moon said, spreading his hands. “I know you’ve financed half a dozen expeditions into the interior—sometimes for zoological purposes, and once even for the Botanical Institute. That’s why I contacted you in Port Durnford when this map came into my hands. I’d have laid my scheme before you there, only—well, this is my territory. I don’t belong on the high-class outskirts of Durnford where you and the lady live.”

“I wish to heaven we didn’t.” Rita commented, sighing, and she looked away to avoid her husband’s coldly reproving glance. Moon’s gaze strayed to her. He liked her youthful figure in the white costume and blouse. He liked her aloof expression, blonde hair, and independent chin. He rarely saw a white woman in the course of his erratic career, and when one as good as this turned up—

“At least tell me where you got the map,” Perrivale suggested. “I’m not financing anything so big as a safari right across the interior without knowing all the details.”

Moon considered this, fingering his underlip gently, his sloe-black eyes on Rita. Then as she caught him out in gazing he said slowly:

“How I got the map is my business, Mr. Perrivale. All I will tell you is that I got it from a Bushongo who had been in a recent safari. He found it amidst a lot of other things in a wallet lying in the clean-picked bones of a skeleton. According to the other things in the wallet, the map was made twenty years ago. In that wallet, what bit could be read of various things like insurance certificates, letters, airport passes, and so on, everything was dated 1932. So, time passes on.”

“And this Bushongo came straight to you?”

“All those who matter do so.” Moon aimed a level glance. “I’m a trader, Mr. Perrivale. It pays me to keep in with the black boys. I get lots of tips that way.”

“And how do you know this map of yours is genuine?”

“Because Mark Hardnell was not the kind of man to go into the bush without good reason. He was looking for Akada, maybe for the same reason that I am now hoping to look for it.”

“Hardnell?” Perrivale scratched his receding chin. “Mmmm—yes, heard of him, though I was I was only a boy at that time. He was a rather crazy, drunken roamer well known in Zanzibar, wasn’t he? Had a wife, I think, who went everywhere with him.”

“Dunno,” Moon said. “But I do know any map found on him must have a genuine purpose. He seemed to have got partly on the way to his objective, too, judging from where that Bushongo found the skeleton. Don’t know what happened. Savage tribe, maybe.”

Silence again, Perrivale weighing matters up. Moon poured out some more whiskey and swallowed it quickly. Rita regarded him with that distant look in her grey eyes.

“Right across the interior, eh?” Perrivale mused.

“That’s it. Across Kenya Colony into the Uganda Country, then into the Belgium Congo region. After that—” Moon checked himself with a grin. “Nearly forgot,” he apologised. “That information has to be paid for, of course.”

“There are more ways of getting a map, Moon, than paying for it,” Perrivale reminded him, with an unpleasant smile.

The sloe-black eyes pinned him. Moon’s voice was dead level: “Don’t get any notions like that, Mr. Perrivale. I know men—and women too—get wiped out like flies around here for various reasons, and there’s rarely an explanation, but that’s because they’re careless. I’m not careless. I know how to look after myself.”

Perrivale nodded. “I can believe it,” he said dryly. “And this safari you’re talking about won’t be any ordinary little thing, not to cover that distance. It’s over fifteen hundred miles to the Belgian Congo from here.”

“I know,” Moon responded calmly. “That’s why I can’t afford it. It’s also a good distance to where Akada stands—but surely it’s worth it?” He leaned on the table, intent and earnest. “In Akada, according to what I know from the map and other details, there must be ivory and gold worth several millions sterling, if it can only be moved. That’s the point. Moving it even when we get there. I can’t afford that kind of help. You can.”

“It’ll need a partially mechanised safari,” Perrivale said, and Moon nodded.

“It will, until we get so deep in the forest we can’t use such things. After that we’ll want the biggest army of tough natives we can find to do the carrying—Damnit man, it’s surely worth fifty-fifty?”

“It’s worth it—if I come with you.”

Moon rubbed his mouth and mused; then Perrivale added: “I want to be sure after financing such an expedition that I get a good return. Your reputation, Moon, isn’t exactly highlighted for honesty!”

“Nope—I wrangle where I can,” Moon grinned. “But in this case I’ve no objection if you want to come.”

His eyes strayed to Rita again. “Better bring your wife, too,” he added. “Unless you trust leaving her behind.”

“Meaning what?” Perrivale demanded, his eyes sharp.

“Meaning a pretty woman with her kind of shape is in danger from every damned louse once her husband isn’t around.”

“The men aren’t like that in our section of Port Durnford!”

“They’re like that anywhere, Mr. Perrivale. There’s more scum in Durnford than you’d think—and as you’d find out if you left your wife behind.” Moon shrugged. “Just a suggestion. I’m looking out for your interests.”

“Kind of you,” Perrivale sneered. “She comes anyway. She always does wherever I go. I agree with you that a pretty woman isn’t safe alone.”

Moon grinned comfortably, and thought of the thousand miles of journey ahead when necessity would throw him in constant contact with Rita Perrivale. It would make the journey really pleasurable.

“It’s settled then,” Perrivale said, getting to his feet. “I’ll make arrangements for the safari. It will start only when you produce your map. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” Moon responded, rising. “I’ll be around this dump for some days yet, waiting for news from you. I’m ready whenever you are.”

Perrivale shook hands and then jerked his head in a completely unmannerly fashion to Rita. She withdrew her hand from Moon’s and felt she wanted to smear her palm down the side of her white skirt. She had a sense of feeling defiled.

Moon watched the two disappear beyond the bead curtains, then he sat down again and dragged out a cheroot, He lighted it, grinned to himself, then ordered more whiskey.

“Such a lot of things can happen in the interior,” he told the native waiter, thinking out loud.

“Yes, bwana,” the waiter agreed and wondered vaguely what the hell the trader was talking about.

* * * *

A safari, sadly depleted from its original strength, made its way slowly along the jungle trail, through the midst of the ugly baobab trees, past mushrooms as large as umbrellas, close by flowers issuing an intoxicating perfume and as viciously active as a steel lash if one came too near, And in all directions were the screams of parrots, the chattering of monkeys, the distant roaring of a challenged lion, and the eternal tsetse-flies hovering in clouds, particularly in the cooler spots and above the eedoo glades.

It was the African afternoon—blazing hot, relentless—even though the sun itself was masked by the dense foliage and the twisted, cable-like lianas overhead. The safari moved slowly, gleaming Bushongos at its head, their dark skins rippling with perfect muscles as they wielded their machetes.

The Europeans at the rear of the long trail moved with lassitude. So far they had escaped the ever-pestilential malaria: drugs had seen to that, as far as Harry Perrivale and Rita were concerned. Caleb Moon seemed to remain on his feet because of the amount of whiskey he consumed. He just sweated everything out of his system and kept on going—but the spirits had done many things to his temper since the long gone day when the journey into the interior had started.

In fact, his temper was the cause of the woefully thinned safari, and when the safari halted its journey for the night, Perrivale said so in no uncertain language. Caleb Moon listened to him, seated on the campstool in his own camp, and going through the routine of looking for chiggers’ eggs in his faded drill suit. The eggs, hatching at body heat, could drive a man or woman to frenzy if not ‘deloused.’

“Less drinking would help, Moon,” Perrivale said, and his dissolute mouth tightened.

Moon grinned. “What d’you expect a man to do in this blasted frying pan? Run around with his tongue out waiting for Mr. Perrivale to say, ‘You can have your water ration now’? I drink when I like, Perrivale—and that’ll be often. You’ve no authority over me. In fact, without me you won’t get anywhere! So get back to your tent and shut up!”

“This safari is mine,” Perrivale retorted. “Thanks to your damned temper, it’s cut in half. The boys are scared of you, flaring up at the least thing. They’re flesh and blood the same as us—and we can’t do without them. We’ll need every man we can get when we reach Akada.”

Moon dragged on his examined shirt. “I’ve handled this kind of scum all my life, Perrivale, and you only get results by making ’em afraid of you. I know my business.”

“Lessen this safari any further and we may as well go right back home,” Perrivale snapped. “Watch yourself, Moon, that’s all.”

Perrivale left, his mood black, and crossed the fire-lighted clearing to his own tent. Within it Rita was doing what she could with her damp tresses, She eyed her husband as he came in.

“Well, did you warn him?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“I doubt it. You’re as scared of him as these poor black devils outside. And a scared man in the jungle is no use to anybody.”

Perrivale glared at her. She studied his reflection through the folding mirror in the lamplight.

“No use denying it, Harry,” she added. “You’ve got plenty of money but precious little nerve. You’ve only come on this expedition because you think there is safety in numbers. Well maybe there was—until the safari thinned out so much. We can’t have more than twenty boys left. If they go—”

“They mustn’t,” Perrivale interrupted, alarm in his voice. “If we were just left to find our way back—we—we just couldn’t.”

Rita finished playing with her hair and turned to him. There was contempt in her grey eyes.

“I wish I’d known you were so yellow when I married you,” she sighed. “Unfortunately, the only yellow I saw was the gold you own. Moon, for all his faults, is tough.”

“Good God, from the way you say that, one would think you prefer him to me!”

Rita shook her head. “I think he’s a beast,” she said deliberately. “And a drunken one too, but I do wonder if that isn’t preferable to being cowardly. That’s the one thing about you, Harry, I just can’t tolerate!”

Perrivale said nothing. He knew she was right, but to a great extent his wealthy parents had been to blame. Whilst they had lived, they had brought him up in cotton wool, under the belief money could buy manhood for him. It had not—and this was the first time he had ever ventured into the merciless jungle. It had frayed his nerves, shortened his temper—

A scream from outside the tent suddenly made Rita start. Perrivale looked up in surprise. Getting to her feet, Rita hurried over to the tent flap and dragged it aside. At that moment she heard the thick, liquor-cracked voice of Caleb Moon shouting:

“You damned louse! I’ll teach you to let the fire go down—!”

There followed the crack of a rhino-lash and a desperate scream.

“Bwana, I slept—I—” But the lash cut off the rest of the words.

“Blasted scum!” Moon screamed, obviously inflamed with liquor. “The more that fire goes down, the more we stand to get attacked by jungle beasts! Sleeping? I’ll show you—”

Again and again the lash came down, and in the light of the subdued fire Rita could see a black figure squirming under the onslaught of Moon’s flashing arm. She also saw other black figures darting off like shadows into the jungle, scared of the white boss’s fury. Rita looked after them helplessly, unable to call since she did not know the mongrel tongue they used.

“Mr. Moon!” she cried angrily, striding towards him. “Stop it! Do you hear me? Stop it!”

In his frenzy Moon took no notice. Rita strode on towards him and finally grasped his arm. He paused for a split second, and then swept his arm back and round, flinging Rita from her feet and sending her stumbling into the undergrowth. Dazed, she lay there, her shoulder throbbing from the blow.

The interval had been enough for the hapless black to make an effort to escape, but the vicious whip brought him down on his knees again. He chattered desperately for mercy, and did not get it. His chattering broke in screams again as the lash flayed across his naked back.

“Next time you’ll keep a fire going!” Moon roared at him.

From his own tent Perrivale stood watching, then he suddenly yanked out the .38 at his hip and took aim. At exactly the same moment Moon caught sight of him in the firelight. Drunk though he was, he was not so confused that he could not act fast. He dropped his whip and aimed his own revolver instead. Flame bit across the dimness, and with a cry Perrivale dropped his weapon and fell, clasping his leg tightly. He remained as he had fallen, his features contorted.

“Harry!” Rita cried in anguish, leaping up from where she had fallen. “Oh, Harry—”

Moon blocked her path, his thick arm encircling her shoulders from the front.

“No you don’t!” he breathed, clutching her. “If that scared louse of a husband of yours has a parked bullet in him, it’s no more than he deserves. I’ve been waiting for this—a legitimate reason for shooting him. You and me will keep going—”

“Let me go!” Rita kicked at him savagely, and the sharp points of her half-boots made him wince—but he did not release her. She struggled vainly to tear free, but only succeeded in being dragged all the closer to the trader.

Then something else happened. Moon saw it first and blinked. A second later he felt it. Something that seemed to be too hard for flesh and bone crashed straight into his face and sent him flying backwards. Half stunned, he flattened in the loam, sparks bursting through his brain.

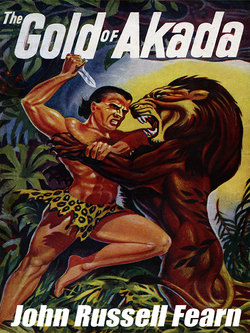

It took him a second or two to recover. He twisted round and stared on something he could not believe. There was a newcomer in the clearing, white-skinned in the dim firelight, his only attire a leopard-pelt about his loins.

“What the hell?” Moon whispered to himself, sobering—then he staggered up and came floundering across the clearing. The newcomer, behind whom Rita was crouching, waited—but he did not strike out.

He was tall beyond the average, possibly six feet four, with power-packed shoulders and chest. His hair, roughly cut, was flung back from his broad forehead, secured with a thong, and was the colour of honey. The hilt of a crude-looking knife projected from the leopard-pelt.

Still Moon stared, unable to credit his senses. Rita backed away and hurried over to her groaning husband. Moon made a half move to follow her but the white giant moved also with one foot, barring the way. Moon peered at him, studying the well-cut features—then as fast as thought his hand blurred down to his gun, and he yanked it out.

Before he could fire the stranger’s right hand shot out and closed round his wrist. The trader gasped as steel fingers tightened relentlessly and all but broke the bone. Then, heavy man though he was, he was lifted in the air and flung with savage force. He struck the bole of a baobab tree on the edge of the clearing, and dropped with half the senses knocked out of him. His gun had gone—so he did the only thing he could. He crept into the jungle and kept on going, completely unable to understand what had happened.

The white stranger turned at last to where Rita was making ineffectual efforts to drag her husband into the tent. With perfect ease the giant lifted the wounded Perrivale in his mighty arms and bore him to the camp bed, laying him down. Rita was too intent on trying to ease her husband’s pain to pay any attention to the white man who now stood with folded arms, watching impassively.

“He—he got me—in the leg,” Perrivale panted, his face sweating. “I don’t know if the bullet’s still there. Take a look.”

He relaxed again on the bed, setting his teeth. Rita looked at him helplessly, her knowledge of first-aid and anatomy practically negligible. Then she seemed to become aware of the silent white man watching her. His advent should have startled her, and indeed it had at the time, but just at the moment her whole attention was given over to her husband.

“Can’t you do something?” she entreated. “He’s been hit in the leg. Look at it.”

The finger pointing towards Perrivale’s blood-soaked trouser leg was enough to get the white giant on the move. He went down on his knees beside the camp bed and tore Perrivale’s trouser leg up the side, then he examined the leg itself, wiping away the blood with a piece of trouser leg. The injury looked worse than it was really, but even so Perrivale had suffered a wound that had gouged deep into the calf and only just missed the bone. The bullet itself had apparently passed on.

Rita, seeing the extent of the damage, turned aside, and heated water on the oil cooker. Then she bathed the wound and bound it up with wadding from the medical kit. Perrivale gave a taut little nod of thanks, the pain of the injury still pretty considerable.

“Thanks, Rita,” he said—and, glancing up at the white giant, “and thanks to you, too. Just who are you, anyway? You’re white.”

Rita eyed the giant with his rippling muscles, keen blue eyes, and finely cut chin. He had blond hair tied back with a thong.

“He’s wonderfully developed,” Rita murmured, admiringly.

The giant made no comment and turned to go, but Rita caught his arm.

“Please—don’t go yet! We want to learn more about you. And besides, Moon might return. If he does, I don’t want to be left to tackle him by myself, as I should be with my husband like this. It will be quite a while before he can be up and about.”

The giant listened in puzzled interest, obviously trying to understand. Rita sighed, but she kept her small hand on his mighty forearm.

“Rita,” she said, pointing to herself, then nodding to the watching man on the camp bed she added, “Harry. Now what is your name?” and, her eyebrows lifting inquiringly, she tapped the giant’s broad chest.

“Rita—Harry,” he repeated in a grave, deep voice that had none of the guttural intonation of a native. And, seeming to grasp the point, he added, “Anjani,” and indicated himself.

“Anjani?” Rita looked interested.

“It means ‘White God’ in some native tongues,” Harry said from the bed. “Don’t let the fellow go, Rita—there’s something queer about him being here in the jungle.”

Rita increased her grip on Anjani’s arm and tugged a little. Finally he seemed to understand, and, smiling, moved back into the tent and waited for what might happen next.

“We must teach him English,” Harry said, relaxing again. “He certainly doesn’t belong in this hell-hole, and I think we ought to find out why. But don’t let him go, Rita—he’s too useful.”

Rita said nothing. It was just beginning to occur to her that, now her husband was wounded, a new cowardice would be added, strengthening the old, and weakening the man. With Anjani at his right hand, there was nothing to stop him keeping in the background whilst the mysterious white giant faced all the dangers.