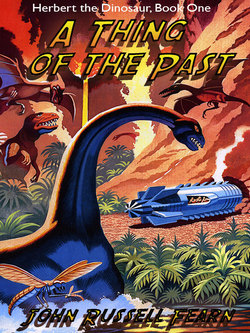

Читать книгу A Thing of the Past - John Russell Fearn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

THE FISSURE

The monstrous face of the basalt cliff lifted outwards under the impact of the explosion. Rocks and subsoil flew. Small boulders flashed to the zenith and rained down amidst a cloud of choking dust. On the hot summer wind a rumbling died away into silence and all was quiet.

“That seems to be it, Mr. Brooks,” the field engineer said, cuffing up his steel helmet and mopping his face. “That’s the last of ’em. Clearance is complete, or will be when the mechanical navvies have finished.”

Clifford Brooks nodded. He was the mining engineer in charge of the whole operation. For six weeks now throughout the unusually hot summer he and his band of iron-hard men had been at work removing a basalt area so that the ever-spreading environs of London could spread even further.

“Better take a look at it, Dick,” he said briefly; “Make sure everything’s as it should be.”

The field engineer nodded and, with Cliff Brooks by his side, he strode across the busy mining area, picking his way amidst the equipment whilst the men lounged around waiting for their next orders.

After a while the two engineers reached the summit of the rubble mountain that the exploded gelignite had ejected. They looked around them in the dust haze. The whole mass of the basalt cliff that had formerly stood in their way was now completely levelled. Once the rubbish was moved, there would be a flat area around here many square miles in extent, in prime condition for laying the foundations of a new building scheme.

“Satisfactory enough,” Cliff Brooks said, nodding. He was a tall, rangy man, rather like the popular conception of a Western hero, his skin a burned-in brown, his eyes blue, his face lean-jawed and extremely determined.

“Hear something?” asked the field engineer after a moment, frowning, his head cocked very slightly.

“Nothing more than usual. Bits of rock dropping, sound of the wind in niches....”

“No, no, a sort of buried rumbling. Listen!” The field engineer held up his brown hand urgently, and now Cliff Brooks heard it too. It sounded like a train at the far end of a very long tunnel. Somehow there was something vaguely frightening about it, an odd suggestion of deep, buried power.

“Sounds like thousands of tons of rubbish going down a deep mine,” the field engineer said. “Where the hell’s it coming from, anyway?”

They began moving again, searching around them in the ruin of debris and rocks, then presently they both halted on the edge of a hole. They looked into it, then at each other. The noise was coming from inside the hole. Down there was a shaft, but what its depth was they could not imagine. Standing there on the edge of the hole, the noises that came from below sounded a thousand miles away.

“Must be some kind of old fissure,” Cliff Brooks said finally. “Certainly not a new one, or a volcanic root, else we’d have had lava and God knows what raining on us by now. Get the boys to bring the tackle. I’m going down to see what it’s like. We’ll probably have to fill it in.”

The field engineer turned away, and then hurried down the slope to give his orders to the waiting men. Cliff Brooks laid flat and peered into the depths, sniffing at the draught blowing upward. It smelled sweet enough—no mephitic gas of any kind—and it was slightly warm. This latter fact he could well understand since the shaft probably connected with the core of volcanic matter somewhere. That core must be a long way off, though, for here in Britain volcanic areas just did not exist—

Then the brawny, sweating men were coming up the slope in the hot afternoon sunlight bearing with them the ropes, trestles, and block and tackle necessary for a descent into the depths. In a very short time they had a cable and harness rigged up, and Cliff made himself comfortable within it.

“Lower away,” he instructed, switching on his torch. “I’ll give the usual signal when I want to come back.”

The field engineer himself took charge of operations, and gradually Cliff found himself descending from the burning sunlight into the warm, dark depths, the draught blowing up past him as he went down. Just at this point the shaft was not very wide; so that his torch beam easily reached the walls on either side. From the appearance of the rock it was plain that the shaft was Nature’s handiwork: the explosion had not unexpectedly revealed some earthwork performed by men in the dim past.

The narrow width of the shaft persisted for nearly two hundred feet, then it suddenly branched away, and Cliff found himself swinging in a great abyss from which all signs of walls had gone. His torch beam completely failed to reach them. Up above there was a pinprick of bright light that marked the spot where the hole opened to the surface.

“Everything all, right, Mr. Brooks?” came the field engineer’s voice over Cliff’s tiny portable radio.

“Okay so far. Keep on lowering me. First time I ever saw a shaft like this. It’s opened now into a big cavern—or something. I’m right in empty air at the moment and it’s getting colder instead of warmer.”

This was a fact. The warm air was apparently escaping into the narrow part of the shaft, possibly from unseen blowholes in the rocks that connected deeply with the Earth’s faraway volcanic depths. Here, in the more open region, the warmth had gone and a glacial coldness was descending. Cliff gave a little shiver as perspiration chilled upon him.

Then suddenly he saw ground coming up to meet him in the torch beam. He landed on his feet without hurt, and gave the “Stay put” pull on the guide rope as he detached himself from the harness. Torch in hand he looked about him, conscious of the intense, sepulchral cold.

He was certainly in some kind of underground cave, great daggers of limestone rock pointing down at him from high above, except from the black hole through which he had come. Then there was that mysterious rumbling note. He could still hear it, much more forcibly now, but it still seemed be coming from below. Drawn on by the fascinating mystery of the whole thing he explored farther, doing his best to disregard the intense cold.

Just in time he stopped himself as he came to the edge of a sheer cliff. Amazed, he stared over it into incomprehensible depths. It seemed incredible that there could be a gorge so vast in the Earth itself. It went into absolute remoteness, but at a colossal distance below there seemed to be something vaguely white. It had a curious phosphorescent quality, for, though he tried to the limit, he could not bring his eyes to focus on this unimaginably faraway phenomenon.

“Okay?” rang out the friendly voice of the field engineer.

“Yes, but frozen stiff. I’m looking at something I don’t understand, some kind of gorge that looks as though it opens into the very core of the Earth itself. That can’t be right, though, else there’d be steam and hellfire coming up. I can see a long slope going down into infinity— Just a moment whilst I try an age-old experiment.”

Turning, Cliff picked up a reasonably heavy boulder, whitish with a glaze of frost. He heaved it into the canyon and then counted the seconds until there should come the sound of the stone arriving, whereby to roughly estimate the distance in feet. But there was no answering sound. As far as he knew the stone never hit bottom, or else the noise of it doing so was lost. The buried, mystic rumbling remained unchanged.

“Deeper than anything man ever encountered before,” he announced into the microphone. “Have to take a proper look at it later—”

He stopped speaking abruptly, his eye catching sight for the first time of a mighty glacier wall to the rear of him. It looked exactly like green glass. This in itself was remarkable enough, testifying to the extreme cold at this particular region in contrast with the warmth of the higher levels—but even more remarkable was the sight of something white and oval very near the outer surface of the glacier wall. Cliff began moving towards it.

“You all right?” came an anxious enquiry. “You stopped talking very suddenly.”

“I’m all right, yes: just looking at something odd.”

Cliff ran his fingers over the iron hard smoothness of the glacier wall’s face, his torch beam fixed on the oval something. It was shaped rather like an egg. It was an egg!

“I’ll be damned,” Cliff muttered; then into the microphone: “Send down a pickaxe, please, right away. I’ve happened on to the biggest egg I ever saw. May be interesting to find out what laid it.”

There was an interval whilst the pickaxe was sent down, then Cliff went to work, carefully nicking the ice away in a big circle from around the mystery object. It took him half an hour to get it free, so scared was he of breaking it. Then he laid it down in its bed of chipped ice and peered at it again in the torchlight. It measured some eighteen inches from tip to tip, and possibly nine inches across. In colour it was muddy brown-white, but appeared to be in perfect condition thanks to the ice that had preserved it.

“I’m coming up again,” he announced, carefully packing the huge egg into the haversack of small tools and odds and ends he had brought with him. “Raise me as carefully as you can.”

He held the egg carefully against him as he was lifted up the shaft once more, and by the time he had reached the top the ice around the egg had completely melted, soaking the haversack and his shirt.

“What the blazes laid a thing like that?” the field engineer asked in amazement as Cliff came out of the harness and held the egg up proudly.

“No idea, but I mean to find out by the simple process of hatching it. May have been down there in the ice for centuries.”

“Any idea why there should be ice down there?” the field engineer asked.

“No idea at all, unless it’s some kind of drift from an underground glacial region, which is quite possible. Take an expert geologist to work that one out.” Cliff’s expression changed slowly as he stood thinking. “Something very queer down there, boys,” he continued. “Warm volcanic draughts, ice cold mass of glacier in which I found this, and a gorge of inconceivable depth going down into— Well I just don’t know what.”

“The answer to all this being what?” the field engineer asked. “Can this region be passed as okay for building?”

Cliff shook his head. “Not yet. For one thing this narrow shaft will have to be thoroughly examined in case there’s a chance of a subsidence later into that big cavern I landed in. This whole area’s in considerable danger of lunging inwards at some future date. I’m taking no responsibility. If the geologists issue a certificate, then that passes the buck to them. Right now there’s nothing more we can do but get this rubbish shovelled up. You look after it, Dick, and I’ll go into town and report to headquarters.”

“Okay,” the field engineer promised, and Cliff went on his way still carrying the mystery egg with infinite care. When he arrived home that evening he still had it with him, but by now it was in a cardboard box lined with cotton wool. With a certain air of mystery, like a magician about to perform a trick, he displayed the egg to his wife.

“What is it?” Joan asked, not particularly pleased at having the untidy old box dumped on the spotlessly white tablecloth.

“An egg,” Cliff said proudly. “The biggest egg you ever saw!”

“I can tell that. What laid it, an ostrich?”

“Heavens, no! An ostrich’s egg would be tiny beside this. I’m going to hatch it out and see what comes of it.”

“Oh, I see.” Joan looked rather stupid for a moment. Not because she really was stupid, but because she could not imagine why anybody should wish to bring home an outsize egg and hatch it just for the hell of it.

“I found it in a glacier nearly three hundred feet down in the ground,” Cliff explained, hoping this information would stir up interest. “Very uncommon happening, I can tell you.”

“Uh-huh— Are you having the remainder of the cold meat or shall I make it up into rissoles?”

“It’ll do as it is,” Cliff replied absently. “Too hot for rissoles, anyway.”

Joan shrugged and wandered off into the kitchen regions. Cliff looked after her and sighed. Joan was a good sort in most things—nice cook, kept the house perfect, only she had very little imagination and relied far too much on gadgets to help her with her work, when a little physical elbow grease might have done her a world of good. Cliff never regretted that he had married her, but he could have wished for a girl slightly quicker on the uptake.

“Be back in a minute,” he called out as crockery rattled in the kitchenette.

“Back? You’ve only just come in. Where are you going?”

“To put the egg in the garage. Warm enough in there this weather to hatch it.”

“Oh!” Just that: nothing more. By the time Cliff had rid himself of the egg, freshened up, and was seated at the table Joan seemed to have forgotten all about the egg until Cliff jogged her memory.

“It’s possible,” he said, musing, “that the egg may have been buried down in that underworld glacier for many hundreds, or even thousands, of years.”

Joan reflected. She was a tired-looking young woman with ash-blonde hair and hazel eyes. Not so bad looking really, only the romance seemed to have gone out of life, and she found married domesticity pretty humdrum. The thought of an egg buried in a glacier for thousands of years was hardly the basis of a pep talk either.

“I’ve seen the geologists,” Cliff continued. “They’re going to explore the cavern where I found the egg and the shaft that leads down to it—” and he went on to explain in detail, including an account of the mighty gorge that he had been quite unable to fathom.

“You surely don’t suppose,” Joan asked at length, “that that egg can possibly have anything in it? Not after the hundreds or thousands of years you so cheerfully speak of. Why, it ought to be—be rotten.”

“Not if preserved in ice, dear. That’s the whole point. Do you realise that living bacteria, perhaps millions of years old, have been dug out of ice from time to time in circumstances very similar to these?”

“Think of that!” Joan went on with her meal. Eggs did not appeal to her in any case, either for eating purposes or for scientific investigation. In fact, the thought of an egg that size made her feel strangely queasy within. Cliff sensed this fact and slightly changed the subject.

“We got the site flattened out all right at last, thank goodness, but I don’t know what’s going to be done about that shaft. Maybe have to fill it in. Make foundations rocky if we—”

The front door bell rang. Throwing down his napkin impatiently he headed out of the room, returning with Bill Masterson, the thick-necked, bull-headed geologist of the mining concern.

“Howdy, Joan,” he greeted briefly, and then settled himself in the nearest armchair. “Don’t let me upset feeding time: I just wanted to tell you personally, Cliff, what I think you’ve run into back at the site.”

Cliff resumed his seat at the table. “You’ve examined he shaft then?”

“Certainly, and the cavern below. That explosion you set off to blow out the basalt opened a natural fissure that leads down into a completely preserved Jurassic Period. No doubt of it whatever. Up to now geologists have been content to find a few fragments of some past age—a bit of Triassic, maybe, or a bit of Eocene, but never have we landed on a whole area preserved exactly as it must have been in that period. You have done science a wonderful service, Cliff, and I intend to let the scientists know that.”

“Well, thanks very much. Sheer chance, anyway.” Cliff frowned as he ate his meal. “How do you mean—perfectly preserved? How could it be?”

“It’s like this. At the depth you reached—three hundred feet down—there was once a surface landscape of the Jurassic Period. Then something must have happened. Maybe a gigantic earthquake, or even a general sliding of the Earth’s surface. That area was covered with rock, but atmospheric pressures—steam pressures, that is, from inside the Earth—formed a gigantic blowhole in the shape of that cavern. A new surface formed over the hole and it’s lain there untouched ever since. As the pressures relaxed and the volcanic heat abated water vapour would form. Its drops caused the stalactites to form in the roof. It was after the Jurassic and Mesozoic Periods, the age of the dinosaurs, that a second glacial epoch descended on the world, and it is possible that that mighty buried glacier is a part of it, still unthawed because down in that huge cave there is so little warmth.”

Silence, save for the clink of knives and forks.

“How long ago did all this happen?” Joan asked finally. “The Jurassic Age, I mean.”

“Oh, around eighty million years ago.”

Joan smiled weakly and made no comment. Cliff, though, stopped eating.

“Eighty million years! But that egg I found just couldn’t be—”

“What egg?” Bill Masterson’s eyebrows went up.

“I found an egg in that glacier wall and dug it out. Maybe you noticed the space in the glacier where I’d been busy?”

“Frankly, no, and if I did I didn’t take particular heed.” The geologist’s face had become grim. “Where’s this egg now?”

“In the garage. I’m hatching it out just to see what’s in it.”

“You may be very horrified when you see what is in it. You surely know enough of geological history to realise that the things that existed eighty million years ago were huge and terrifying? The age of the dinosaurs, man!”

“Yes, but— This couldn’t be a dinosaur. It’s an egg. It can’t mean anything more than a bird.”

Bill Masterson sighed. “For your information, Cliff, the vertebrated animals of the Jurassic Age laid eggs. They did not procreate in the manner of the later, more refined creatures. If you take my advice you’ll smash up this egg from the glacier before things get too tough.”

Cliff shook his head. “I’m too inquisitive to do that. If something horrible turns up I can very soon destroy it. But I’m certainly going to see that egg hatch.”

“Very well.” The geologist gave a shrug. “Don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

“What about that deeper cavern, or canyon, which Cliff found?” Joan enquired, slowly becoming interested. “Any ideas on that, Bill?”

“I’m afraid not. I think the buried rumbling may be from great internal activity, or it may be the action of a mighty underground ocean.” Bill pondered for a moment. “Yes, on reflection I think an ocean is the best theory. If it were internal fire, there’d definitely be more warmth coming up the gorge than there is.”

“An underground ocean seems to suggest a whole world within the world,” Cliff said.

“Is that so impossible? If part of the Jurassic Age could be buried, so might a great deal more of it, or even parts of other Ages. I can’t help wishing with all my heart that that shaft had never been opened by the explosion, Cliff.”

Cliff grinned. “It was just one of those things, and I’ll be hanged if I see what you’re bothered about. Putting aside the scientific issue for the moment, what do we do with the site? Fill it in?”

“Yes.” Masterson got to his feet. “As quickly as possible, too. Just in case there might be a volcanic upsurge that would blow half of England off the map. You don’t seem to realise that you’ve opened up a vent in this old planet of ours. The effect is not seen immediately, but it may cause a redistribution of internal pressures, and then anything could happen. Yes, get the shaft blocked as fast as possible. Concrete and liquid iron. That should hold things.”

“And what about the scientists? They’ll want to have a look at this geologic masterpiece, won’t they?”

“They can do it within the next week; you won’t have filled the shaft in by then—” Masterson glanced at his watch. “Well, I’ve got to be going, but I thought you’d like the facts before I turn in the official report. I’ll tip off the scientists to come and have a look if you like.”

Cliff nodded. “Do that. Tomorrow I’ll have the boys start the sealing process.”

On that the geologist departed, and Cliff stood thinking, gazing through the wide-open window towards the garage at the bottom of the garden.

“You thinking what I’m thinking?” Joan asked him, drifting to his side.

“I don’t know. It just crossed my mind that I’m sticking to that egg, no matter what. I can’t see what Bill’s getting goose pimples about. If there’s anything queer in the egg, it can be put to sleep instantly.”

“No guarantee it will even hatch.”

With a mutual thought in their minds and their meal over, they strolled out through the kitchenette door into the garden. The evening was hot and misty with a promise of thunder to come. These were everyday phenomena, though. In the garage there was a thing of the past, and down under the Earth there was also a region upon which man had never set eyes for eighty million years until Cliff had descended the shaft.

“No harm in seeing how the egg’s going on,” he said as he and Joan reached the garage doors.

“No harm at all. That’s why we’re out here, isn’t it?”

Cliff opened the doors and looked on the floor at the rear of his two-seater car. The egg was in the cardboard box as he had left it, the lid removed. Nothing had happened yet, anyway.

“Perhaps not warm enough,” Joan said.

“I think it’s just right, dear. The period from which this egg came, far as I can remember, was mild and humid—much as it is tonight. The conditions are quite favourable. Don’t forget it has to thaw out from the glacier as well.”

Joan stooped and sniffed at the shell. “Doesn’t smell at all, does it?”

“No reason why it should. It was probably quite fresh when the ice or whatever it was caught up. We’ll leave it for a day or two and see what happens.”

For an instant it was in Cliff’s mind to put his foot into the egg there and then, so strongly did Bill Masterson’s sombre warning cross his memory; then he shook his head to himself and closed the garage doors adamantly. He turned to find Joan looking into the misty sky. The sun was hidden in the heat haze low down on the horizon, so it was no effort to stare at the heavens for a prolonged period.

“What is it?” Cliff asked, expecting to see some aerobatics by a jet plane.

“That! I’m trying to make out what it is. Some sort of noiseless plane, isn’t it? I’ve heard that there is one on the secret list—”

Cliff looked long and earnestly, and at last he found the object that Joan’s sharper eyes had already detected. It was circling at a height of perhaps three hundred feet, making no sound whatever. Occasionally it dived; then it climbed again with the velocity of an anti-aircraft shell. In some ways it looked like an airplane. In other ways it looked like a bird— Bird? Impossible! There couldn’t be a bird of that size, not even the biggest eagle ever known. Why, at close quarters it must be gigantic. It was large enough even seen from three hundred feet below.

“What in the world is it?” Joan demanded at last. For answer Cliff fled into the house and returned after moment or two with powerful field glasses. Quickly he focussed them as he stared aloft.

“For the love of heaven!” he gasped. “It’s—it’s a pterodactyl! A flying lizard!”

“Huh?” Joan looked blankly at his startled face; then he thrust the glasses into her hands.

“Look for yourself! You’ve seen drawings of pterodactyls as much as I have. If that isn’t one I’m crazy!”

Joan looked, only to confirm Cliff’s opinion. The flying horror was partly like a bat, partly like a lizard and having a gun-grey body of apparently tremendous toughness. At a rough estimate Joan guessed the wingspan to be about eighty feet. It kept on circling steadily as if searching for some thing—or else sighting some object or other with its intensely keen eyes.

“It’s crazy, but it’s right,” Joan exclaimed, lowering the glasses. “Or is it right? Maybe it’s some kid’s toy kite shaped like a monster. You know how the youngsters play around with scientific things these days—”

“No use kidding ourselves, Joan; it’s a pterodactyl. And there’s only one place where it could have come from, and that is the shaft of the mining site. Being a bird it could easily fly from its underground prison.”

“But you didn’t see anything alive down there, did you?”

“No, but according to Bill Masterson a Jurassic cavern or something has been opened, and there could have been life that deeper canyon which I didn’t explore. The fact remains: that object up there couldn’t have come from anywhere else.”

They stood watching it for a time as its gyrations grew gradually less, until finally it seemed to be hovering far above, motionless.

“What’s it looking for, do you think?” Joan’s eyes were commencing to ache with the constant effort of staring aloft.

“I’m not sure, but I can hazard an uneasy guess. Right in this garage we have something prehistoric, and by some telepathic link, such as does exist among many birds and animals, that flying horror may be aware that an object of its own time and kin is down here.”

“Sort of inverted homing instinct, or something?”

“Like that—yes.” Cliff had the field glasses still to his eyes—then suddenly he let out a gasp.

“It’s diving!” Joan cried at the same moment. “Quickly! Into the house!”

With appalling swiftness the pterodactyl suddenly began a power dive, swooping with incredible speed from the misty heights, straight down towards the garden. Tripping and tumbling, Cliff and Joan blundered towards the house, gained the kitchenette and slammed the door. Then at top speed they raced into the adjoining living room and watched through the window. Spellbound they watched a scene that had certainly never been viewed before by modern beings.

The pterodactyl had reached the garden, and its size was apparent now as its great wings, dry and membranous, overspread the width of the lawn and became partly entangled with the parting fences on either side. It had a body as big as a man’s, yet a head like a vulture on an enormous scale. It was quite the vilest thing ever, its tremendously strong beak pecking and lashing at the strong garage doors.

“I—I feel sort of sick,” Joan whispered, white-faced. “What in the world do we do now?”

“Nothing,” Cliff snapped. “That thing’s carnivorous, and unlike the modern bird, it has triple rows of shark teeth. I just caught a glimpse of them. If we try and deal with that thing we’ll be ripped to pieces. It’s after that damned egg, sure as fate.”

“Call the police,” Joan urged. “They’ll do something.”

“Not on your life! The police might as well try and fight a tank as fight this. Leave it alone and watch what happens.”

Apparently the terrifying creature was becoming annoyed at finding the garage doors too tough for its onslaught. With a series of ear-splitting screams it flung itself in leathery fury against the barrier, its vast beak tearing great shards and splinters out of the woodwork—but the doors held, and at last the pterodactyl seemed to realise it was beaten. It withdrew and folded its wings, standing for a moment in the centre of the lawn like a colossal bat, its evil head turning slowly until a lidless, deep red eye became visible to the crouching two in the lounge.

“The size of it!” Joan panted. “I’d say it’s nearly twenty feet high!”

“Nearer thirty— Ah! Thank God for that!”

The flying lizard had suddenly spread its wings again and, with another piercing, unearthly scream, it took off into the evening mist and was gradually lost to sight. The only trace of it ever having been present at all lay in the battered garage doors and huge three-claw imprints in the soft soil of the flowerbeds. It had been no nightmare then. The past had come into the present and there was no foreseeing the repercussions.