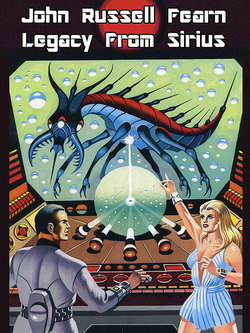

Читать книгу Legacy from Sirius - John Russell Fearn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Robert Driscoll entered the sanctum of the President of the World Council with some nervousness. All the time he had been journeying by rocket-plane to this gigantic edifice, wherein was controlled the political and social destiny of the world, he had been wondering—wondering what on Earth could the President want with him? His position as Chief Observer for the New Mount Wilson Observatory gave him considerable standing, of course, but surely not enough to warrant a summons from the great man himself.

Bob Driscoll’s speculations came to a stop when he finally arrived before President Alroyd’s big desk. He stood looking upon a grey-haired, kindly man, beloved indeed by all the peoples of the world. Alroyd possessed the rare gift of being able to rule and still remain a human being.

“Have a seat, Mr. Driscoll,” he invited, motioning. “I’m sorry I had to call you all the way from California, but it’s most important. Indeed vitally important. I did not wish to entrust my information to television instructions for fear of something leaking out. That, you see, might have caused a panic.”

Bob Driscoll did not see, even though he nodded profoundly. He took his seat and saw the President’s grey hair haloed by the glow through the gigantic window. Outside, the spring sun was westering. In the distance, over a formidable barrier of soaring roofs a rocket-liner went down to its base.

“You will be aware,” the President said, “as indeed everybody in the world must be by now, that we are enduring the most violent earthquakes in history. They keep on recurring without warning, and no scientists seem able to account for them—except to extend the rather nebulous theory that the Earth is becoming unstable and showing the first signs of breaking up.”

Bob Driscoll nodded. “I’ve heard the reports, sir, even though I haven’t experienced anything of that nature myself.”

“The disasters are far-reaching.” Alroyd rose to his feet, a tall, kingly man in sober regalia. “And we have got to get at the reason for them to see if something cannot be done to stop them, or at least forecast where they will happen next. That would give us time to save much life and valuable property. As it is, New York, London, Paris, Rio, and several other big cities have been shaken to the depths. Every day I receive fresh news of mounting death rolls, loss of property and priceless works of art....”

Bob Driscoll made no comment. Being still fairly young—thirty-four, to be exact—he would have preferred to come straight to the point. His good-looking face and keen blue eyes must have shown as much, for the President suddenly smiled and came round his big desk.

“We believe, Mr. Driscoll, that you and your fellow astronomers can help us,” he explained. “Since an internal cause of the earthquakes cannot be detected, it seems logical to assume that the trouble might lie in the cosmos.”

“In—what way, sir?” Bob asked, having the feeling that it was possible the President did not know what he was talking about.

“I, personally, am not an astronomer,” Alroyd smiled. “But I have been informed by various scientific experts that the cause of our troubles might lie in something of the order of neutronium, densely heavy matter which in its passage through space is swinging all the planets in the solar system slightly out of balance by reason of its preponderant gravity.”

“Yes, sir, I suppose that’s feasible,” Bob admitted. “It can be checked by the orbital movements of other planets.”

“That is your sphere, Mr. Driscoll. What the Council wishes is for you to examine the problem with your fellow astronomers and then report your findings back to me. And remember!” The President raised a warning finger. “Not one word of this must go beyond the immediate scientific field it concerns. One hint that the world might be in danger would bring social and economic ruin down upon us.”

“I understand perfectly, sir.” Bob rose to his feet, sensing the interview was nearly closed. “The moment I have an answer, I’ll come personally to report it.”

“Splendid! And thank you for coming.”

Bob shook the hand of the ruler of the world and departed in something of a daze. He was troubled, too, more than he cared to admit. He had been hearing of the great earthquakes for several months now, and, like everybody else, had given them a good deal of thought, chiefly from the angle of a scientist. But he had never expected for a moment that he would be singled out as the man to explain them.

“Rather too much responsibility for my liking,” he muttered, as he boarded the California-bound rocket-liner. “Don’t know why I didn’t take up a quiet life as a machine-hand or something instead of astronomy. If I don’t provide a satisfactory answer to a command like this, I’m liable to lose my job, which in these days is not a pleasant thought.”

All the way back to California from Washington he sat musing on the problem, hardly noticing the sky through which the liner hurtled, or the ever-changing pattern of the land below. He only got a grip on things again when the liner touched down at Los Angeles rocket-port. From here he took his own private helicopter to the heights of Mount Wilson where, on a massive and lonely peak, its top flattened by engineering genius, stood the greatest observatory in the world. It floated eternally above what few clouds there were in the Californian heavens. From it went forth all the world’s astronomical information.

Bob hurried through the various clerical offices until he came to the radio-room. Here he sat down and switched on the microphone connecting to speakers throughout the complicated building. Briefly he summed up his interview with the President, his words being transmitted not only to his own immediate staff but on private wavebands to every observatory throughout the world.

“So there it is, people,” he concluded, cutting out the world-waveband and dealing only with his own staff—composed of twelve of the country’s most expert cosmic-charters and astronomers. “Go to it. Get to the checking rooms and handle the reports as they come through. I’ll go to work with ‘Tiny’.”

In various departments the men and women scattered, and Bob strode on his way to the observatory proper. He was thankful that so far the earthquakes had not shaken these remote heights of Mount Wilson, for the slightest disturbance might have thrown ‘Tiny’ right out of gear, and likewise thrown away some millions of American dollars.

As he walked over to ‘Tiny’s control-chair Bob felt once again that inescapable feeling and awe as he surveyed the giant—the world’s greatest reflector, the utmost that the science and lensmen of this advanced age could produce. The 400-inch monster had an incredibly powerful magnification. Earth’s nearest neighbour the moon—at an apparent distance of twelve miles—had been charted with absolute exactitude.

Bob seated himself, waiting for the roof dome to part in two hemispheres. Once this happened and the blaze of the night sky was above him, he began operating the mechanism. As he worked, he glanced now and again into the starry deeps—and smiled. Perched up here, wielding this giant, he felt like some superman peering into the beginning and end of the universe.

A faint click announced that the reflector was in position. Following out the cosmography he had learned so thoroughly, Bob started on his stellar check-up, giving his findings into the audiophone at his side. In turn this data was relayed to the checking rooms where the astronomical staff went to work with computers, spectro-checkers, and the other advanced appliances of their art.

“Neutronium!” Bob growled to himself presently, as he worked. “Wonder who in heck fed the President with that idea? Mmm—could be the solution, though, come to think of it, but if that were so the nearer planets would long since have developed bulges pulling out towards that excess gravity field.”

‘Tiny’ swung silently on his mighty gimbals.

“Nothing doing,” Bob muttered. “Mars, Venus, and even semi-plasmic old man Jove are all unchanged. Takes a bit of understanding! If these earthquakes are not caused internally or externally, what the devil is the explanation?”

He sat back from the controls wearily, pinching thumb and fingers to his eyes. His vision was strained with so much lens work and the study of display readings. Then as he sat there a sound caught his attention through the open dome—the thin, high scream of a descending rocket-plane. Somebody—and he knew whom—was heading for these heights of Olympus.

He waited, smiling in anticipation. He turned in the chair, his keen blue eyes lighting with pleasure as at last the observatory door opened and a slender figure in flying kit came hurrying across the waste of floor.

“Hello there, Bob!” The girl pulled off her helmet and shook free a mass of ash-blonde hair. “I thought I’d find you snooping around among the stars as usual. Beats me how you can stand the monotony!”

“I have to—or starve.” Bob scrambled out of the control-chair and came forward to embrace the girl, then he held her a little away from him, studying her clear-cut sensitive features. It was rare indeed that he had the chance to see her. Her occupation as ace rocket-flier and leader of the Women’s League of Rocketeers kept her fully occupied.

“Mona Driscoll,” Bob said severely, all of a sudden, “I’ve a bone to pick with you! This Observatory is State property, and I’ve told you time and time again that the partners of employees are not allowed to....”

“Oh, skip it, Bob! Who’d crawl up six thousand feet of rock to check on your morals, anyway?” Mona gave her little ironical smile. “And anyway, you flatter yourself!” she continued. “I didn’t come to gaze on your angelic face but to discover if you know anything about these earthquakes. Have you, perched up here like the Statue of Liberty, the remotest idea of what is going on below?”

Bob’s lips tightened a trifle. He hedged.

“I’ve—heard, of course. Matter of fact, that’s mainly the reason I’m here with ‘Tiny’. I’m looking for a cosmic cause of the disturbances....”

“A cosmic cause? Good Lord, what do you expect to find way up among the stars to explain things? Sounds crazy to me—but then I’m only a woman with a smaller brain than a man.”

Bob grinned. “Bird-brain or otherwise, darling, you still rate aces to me. As for finding explanations among the stars, I too, think it’s haywire. But the high-ups have fed the President some kind of story about neutronium.”

“Neutronium!” Mona gave her cynical smile. “My eye! If it were neutronium trouble we’d be having tremendous tides—and we haven’t had; not any more than the quakes caused, anyway.... No,” she continued seriously, “I think the trouble is deep in the Earth itself somewhere. From what I’ve seen of the ruins of Frisco, London, Paris, and other places, it looks as though the solution lies in internal explosions....”

“Without joking, you really think so?” Bob questioned.

“Uh-huh. Mind you, my geology has cobwebs on it, but I do think that if there were a way to study the roots of volcanoes we might get somewhere. Some volcanoes I’ve seen are blowing off hell whilst others are dead quiet for the first time in centuries. That seems to suggest a redistribution of underground pressure...or does it?”

“Maybe.” Bob thought for a moment and then gave a shrug. “Anyway, it makes no difference. You and I will keep on doing as we’re told and stifle all natural urges to suggest something original—and by the way, what I’ve been telling you is a top-line secret. Not a word to anybody!”

Mona chuckled. “Great heavens, Bob, whoever heard of a woman talking?”

“Look, Mona, please be serious...!”

“All right, all right. I shan’t tell a soul. You know me better than that, or should.”

“Incidentally,” Bob said, remembering something, “what were you doing in the danger spots like London, Paris, and so on?”

“Collecting important State documents—and occasionally people not so important—and flying them to places of safety. Supposed to be safe, anyway.” She moved across to the control chair of the reflector, and lounged against it.

Bob stood thinking, hands in his pockets. “Mona, if these earthquakes go on....”

“We go out.” She raised a shoulder. “The world will fold up like a conjuror’s egg. Well—so what? We all die sometime. Just one of those things. Somehow, though, when you fly through the stratosphere at supersonic speed and get so close to the remoter deeps of space without actually touching them you don’t feel afraid of dying. Neither should you, always gazing—up there!”

She turned and gazed at the twinkling diadem beyond ‘Tiny’s’ mighty bulk. Bob gazed with her for a moment, caught in thrall by the immensity of space.

“I’m twenty-four now,” Mona said, musing. “If I quit this mortal stage before I’m spreading myself out as a matron of sixty, it’ll be all to the good. Think of my lines, beloved....”

She turned to meet Bob’s serious eyes. Her smile faded.

“Just can’t be serious, can you?” he asked, sighing. “For myself I think it’s ghastly to think that we might be swallowed up by an inferno before we’ve even had the chance to find out much about each other.”

“Maybe we’ll die never knowing what we’ve missed,” she reflected. Then she wrinkled her nose. “That sounds confoundedly morbid, come to think of it.”

“Science ought to get busy!” Bob declared.

“Doing what?”

“We ought to have perfected and simplified space travel for one thing. Made it safer and easier—put it on a commercial basis, like we have with air travel.”

“Supposing we had? The public would never take the risks. I know astronomers have a good idea of what dangers to expect on other worlds, but we don’t know everything.”

“We would with my projector as the white mouse,” Bob said slowly.

“Projector?” Mona stared at him. “What projector? Don’t tell me you’ve a magic lantern hidden away in that shack we call home.”

“No, nothing like that. Just a theory I’ve got. Forget it. An idea I’ve doped out between times. Sometimes I have nothing to do up here but sit and think—and then I get the most marvellous notions.”

“Maybe the altitude,” Mona murmured, then turned and looked at the reflector. At the moment the tremendous mirror upon which it was focussed was blank.

“Any chance of one tiny little peep?” she asked coyly.

Bob sighed. “Oh, so you’re after a star tour again, are you? One might think this reflector was installed purely for the spouses of astronomers to come and look through.”

“Only one spouse, darling—or is there something I don’t know about?”

“Stop clowning, can’t you?” Bob roared; then he checked himself. “Okay—no harm in a little tour, I guess. The staff are busy at the moment checking on what they’ve got. Now, where’d you want to go?”

“Suppose you tell me? That’ll give you a fine chance.”

Bob gave her a look, so Mona relaxed and waited as the monster came to life again. Her eyes lighted with genuine pleasure. Bob stood beside her at the rail and together they gazed down on the mirror as the mammoth probe crawled at random through the firmament.

“There’s something about this that always gets me,” Mona whispered. “I don’t know exactly what is it: perhaps the goddess in my wild soul.”

“Peeping into eternity like this certainly does hit you in the eye,” Bob acknowledged.

“Come to think of it, it would be rather wonderful if we could get safer and easier space travel. Be much better than strato-flying, anyway. That has so many limitations....”

Mona suddenly stopped talking—so suddenly indeed that Bob glanced at her in surprise.

“Anything wrong?” he enquired.

Mona did not answer. All recollection of what she had been saying seemed to have gone out of her head. She pointed to the reflector-mirror with a somewhat unsteady hand, pointed to a star which shone balefully bright. In the main it was blue-white, varying at times to an almost Martian red, then back once more to white.

“Bob, what star is that?”

All the habitual levity had gone from the girl’s voice. It was strained; taut as steel wire.

“Why, Sirius,” Bob answered, still astonished. “About the brightest star in the heavens. Star A in Canis Major, distance 8.7 light years....”

“It’s horrible!” Mona whispered, and her face was drawn as she watched the star move through the graded squares on the mirror. “It’s the most horrible thing I’ve ever seen!” she declared passionately.

Bob gave a rather uneasy laugh. “But that’s absurd, Mona! It’s really quite beautiful, especially now when one can sort of see it at such close quarters....”

He stopped, dumbfounded. Mona’s legs had suddenly given way and she dropped soundlessly to the polished metal flooring. For about five seconds Bob just could not believe it. Mona, of the steel nerves, who was not afraid of dying, going out in a faint? Then he came to himself and lifted her limp body in his arms, depositing her in the control chair. Reaching out, he stopped the reflector mechanism.

“Mona,” he said sharply. “Mona, what’s wrong?”

For a while she lay sprawled in the snug grip of the chair; then, as he rubbed her hands vigorously, she began to show signs of recovery.

“Darling, what’s wrong?” Bob caught her shoulders tightly and looked into her face as colour began to return to it.

She smiled wanly. “You’re asking me! I—I— What on earth happened, anyway?”

“Why, you were talking about Sirius and then suddenly you went out like a blown flame.” Bob grinned reassuringly. “Maybe it’s the air up here. It does get you right in the middle sometimes. I’ve bowled over before today, especially with the dome open. Can’t keep the air at normal pressure.” He stopped and frowned. “But that should make your nose bleed,” he mused. “And it isn’t doing so.”

“Maybe it would if you punched me on it for being such a fool.”

There was silence for a moment, then Mona struggled unsteadily to her feet.

“No, it isn’t the altitude,” she decided. “I’ve been way up in the sky before today without an oxygen mask and my heart never missed a beat. First time in my life I ever did that. I just don’t understand it! Maybe the old ticker’s a bit overstrained from extreme acceleration. I’ve been doing a lot of fast rocket-flying lately.”

Bob gripped her arm. “Better see a doctor, Mona. Promise me you will.”

“You bet I will! I can’t go risking other people’s lives in a plane if I’m liable to go out like that....” Mona turned and gazed at the now blank mirror. “Almost looked as if something happened to me when I gazed at Sirius, didn’t it? First time I’ve ever seen Sirius close up.”

“Truly, but at other times we’ve viewed different parts of the heavens.” Bob made a gesture. “Hang it all, dear, this is absurd. How could Sirius...?”

“Of course, how could it?” she exclaimed; then she smiled with something like her old carelessness and picked up her flying helmet from the table. “Just the same, Bob, I’m taking no more tours with ‘Tiny’ until I find out what’s wrong with me. Maybe I’ve got astrophobia.”

“Huh? What in blazes is that?”

“Fear of heights. Standing gazing into space on that mirror is a pretty dizzy business at that.”

Bob nodded slowly, frowning. It struck him that Mona’s conclusion was illogical. An ace strato-pilot bowling over just through looking into a space-mirror...?

“Well....” Mona tightened the helmet strap under her chin. “That seems to be all, except for goodbye. I’ve got to get back to the airport. No, no, don’t worry about me!” she added quickly. “I’ll be quite all right. See you at home—I hope.”

She had been striding across the polished floor as she spoke; now the door closed behind her. A few minutes later Bob heard her fast rocket-plane scream over the Observatory’s lofty height. Through the big window he watched it descending in an ‘S’ of sparks towards the cloud-pack low down in the moonlight. Below, far below, lay Los Angeles.

Moodily, shaken by Mona’s queer lapse, he turned back again to ‘Tiny’, switched it on again and studied Sirius for himself, long and earnestly. Certainly he could not see anything about it to occasion horror—nor did he feel unbalanced in any way. Finally he decided to study the data concerning the star.

“Spectrum deficient in dark lines, proving metallic absorption,” he muttered. “Star not surrounded by metallic vapours, thereby putting it in Class B, totally apart from the G-type dwarf like our own Sun. A hydrogen envelope, mostly transparent....” He closed the file and scowled. “Damned if I know why I’m reading this stuff anyway!”

“Hello there!” the loudspeaker bawled suddenly, and Bob gave a start. He reached across and snapped on the microphone.

“Yes? What’s wrong?”

It was the checking department. “Say, Bob, there’s nothing here that shows any divergence. Better carry on with the eastern section. Whoever figured that neutronium might be out in space must have been nuts.”

“I’m inclined to agree with you,” Bob responded. “I’ll carry on. Stand by for reports.”

He switched off and with a troubled frown reseated himself in the control chair and went to work.

* * * * * * *

Once she had arrived at the Los Angeles airport Mona went to the briefing room for her instructions, and found that they gave her about forty-five minutes breathing space before she had to take off for Rio. Just enough time in fact to see the airport surgeon.

As it happened he was on night duty, and greeted her in his usual matter-of-fact style as she walked into his office. He knew her well enough, since routine physical check-ups were the law for all men and women pilots engaged on public work.

“I think Bob may have been right, Mona,” he commented, when she had outlined her disorder. “Probably the altitude. Anyway, I’ll have a look. Step over here, will you?”

Gone were the days when a doctor had need to poke and probe. Mona simply stepped, fully clothed as she was, into a cabinet and the surgeon closed the door upon her. Beneath a battery of radiations, predominant amongst which were X-rays, every detail of her physique was reflected on to screens. Meters and gauges automatically showed respiration, heartbeats, and blood pressure.

Finally the surgeon switched off, unlocked the cabinet and Mona stepped out to find him considering his notes.

“I’ve seen a few healthy young women in my time, but few like you,” he commented, smiling. “You check up in every detail, Mona—and with a heart like yours, you ought to live to be a hundred and fifty.”

“You’re not—just cheering me up, doc?” Mona asked, seriously.

“Why on earth should I? I state facts as I find them....” The surgeon put down his notebook and frowned at her. “What are you worrying about, girl? This machine does not lie, and it says you are in perfect health. Your fainting spell was purely the attenuated air of that Observatory; I’m sure of it.”

“Yes—I suppose so.” Mona reflected for a moment, and then she gave her sunny smile. “I’ve never been the worrying type, so I suppose I shouldn’t start now. It’s not the faint that has me worried, doc, but something else. The feeling of awful revulsion I had when I looked at Sirius in that reflector mirror. It was as though I’d looked at something indescribably obscene.”

The surgeon shrugged. “Can’t help you there, Mona. It’s a mental reaction and a psychiatrist’s job: I only deal with the body....”

He broke off, alert and listening. Mona, too, detected at the same moment a distant bass rolling sound. It only took her a second or two to interpret it—the same dreaded note she had heard in many a stricken city—

“Earthquake!” she gasped. “No doubt of it....”

She flung herself to the doorway with the doctor immediately behind her. The instant she reached the corridor the earthquake arrived in all its shattering fury. The rumbling became a roar, drumming above the steady crack of fissuring walls. Mona reeled and stumbled her way along the main corridor of the medical department, surrounded now by nurses and medical students who had also nothing in mind save escaping the disaster.

Panting for breath Mona reeled outside into the big open quadrangle of the building. Behind her, the big main edifice split and crumpled like grey tissue paper. Dazed she looked around her. The metal flooring of the quadrangle was splitting in all directions. In the distance buildings were visibly swinging out of the perpendicular and then avalanching downwards. Fire spurted reddishly in all directions; electric sparks flew as cables became entangled with metal. And the vast, overpowering din which gulped and rolled from the Earth’s interior—

Then silence. So sudden it was startling. Steam hissed from somewhere. A chunk of metal dropped with a clang. Mona stood looking about her, disturbed air currents blowing a fast rising wind past her face. She began moving through the excitedly chattering medical staff, inwardly astonished at finding herself alive. Apparently the quake had been severe, but not of very long duration. Many light-standards were still standing, though some of them were drunkenly tilted.

She gained the main airport field to find that nothing was much disturbed. Her own rocket-flyer was just as she had left it.

“What’s the damage, Harry?” she asked one of the ground mechanics.

“Pretty bad,” Mrs. Driscoll,” he answered grimly. “Just had word through. Quake destroyed all eastern Los Angeles. We got the tail end of it.”

Mona sighed as she climbed through the doorway of the flyer’s control cabin.

“Bang goes our happy home,” she commented. “It was in that part of the city. It’s getting these days that you don’t know where to settle.”

“Sure is,” the mechanic agreed, and slammed the cabin door.

At the same moment the door of the Mount Wilson Observatory opened, and Professor Leeman, curator of the observatory and astronomical figurehead throughout the world, came silently across the polished floor. Bob, at the end of his night’s work on the reflector, turned in his control chair.

“Hello, Professor,” he greeted respectfully. “I was just wrapping things up for the night.”

Leeman nodded. He was a tall, gaunt, eagle-like being—forbidding in appearance yet good-natured enough upon close acquaintance.

“Feel the quake?” he asked brusquely, aiming sharp grey eyes.

“Slightly,” Bob acknowledged. “Up here we have the mass of the mountain to support us. Just as well, too with so many valuable instruments about.”

“Just so. I hear that all eastern Los Angeles has been smashed. Hundreds dead. Same old story.”

Bob said nothing, his mind flashing instantly to Mona. He could only hope that she had been in the air when the quake had struck.

“I have here a report from the geologists,” Leeman continued, taking a printed sheet from his inside pocket. “It makes hay of the idea that neutronium might be causing the earthquake trouble. Seismographers and geologists working together have positive evidence of an internal volcanic cause, so we can call the search for neutronium definitely off.”

“I understand, sir,” Bob assented. “And what about the President? Am I to tell him that?”

Leeman smiled frostily. “I have already done so. Naturally, it is no secret to any of us here that he gave you special orders. As chief curator my position ranks with yours.”

Bob said nothing. If anything, the curator was a niche higher, but he never traded on his superiority.

“What we have to do,” Leeman continued, “is follow out new Presidential orders. The geologists hold out little hope of stopping these quakes—so we have to prepare accordingly. The Space Agency have received orders to build Space Arks on the rocket-principle.... An ill-starred project, to my mind,” Leeman finished gloomily. “However, the hand of urgency is pushing us. So, then, with your staff you will work out a full report on Mars—the only planet that we might hope to colonize. That clear?”

“Clear enough, sir,” Bob agreed, reflecting. “Only I don’t really see we have much to add to information already gained from the probes we sent to Mars years ago. Planets don’t change much. Our trouble is, we don’t have any probes there at the moment that are still transmitting. The government have scaled right back on expenditure on space exploration these last few years....”

“That’s about to change,” Leeman replied, with his usual brevity. “Anyway, those are the orders, Bob; I’m leaving it to you to carry them out.”

With that he departed, leaving Bob looking thoughtfully after him. Fifteen minutes later Bob was leaving the Observatory for his State-maintained home two miles further along the mountain road. Actually, as Mona herself had remarked, it was little more than a large shack—but it served its purpose during long periods off duty. Besides, it gave him a place wherein to experiment.

He had only just risen from sleep the following afternoon when Mona came in, pulling off her flying kit wearily.

“Thank heaven you’re still safe!” Bob greeted her. “I’ve had the wind up properly after that earthquake.... Did you see a doctor as you promised?”

“Uh-huh, and I think I must have been his last patient. I’m not sure whether or not he died in the earthquake. I only just escaped in time.”

“Oh.... Well, what did he say?”

“Nothing the matter with me,” Mona answered tiredly. “Nerves like cast iron, normal blood pressure, tough heart—I’m one hell of a woman in fact! But gosh, right now I’m worn out!” She sank down on the bed edge and looked at Bob with drowsy eyes. “I’ve been flying like a scalded hen ever since I left you last night—and talking of earthquakes, this is our home until we rebuild or everything drops to bits. Our suburb in Los Angeles collapsed last night and our ancestral pile with it. I flew across the region to make sure. So there it is.”

“One home less to bother about,” Bob growled, commencing to shave vigorously.

Mona was silent for a moment; then she asked:

“Anything fresh with you?”

“Not really—’cept that we’re not looking for neutronium anymore. The geologists now believe an internal trouble is the cause of the quakes—same as you said. Our job at the Observatory is to find out everything we can about Mars, to which the high-ups are planning to evacuate some remnants of humanity. Tall order! You realize what it means, Mona? The Earth is considered doomed.”

“Yes, I know.” Mona’s voice was listless. “The flying I’ve done recently has shown me that there are crack-ups everywhere. It’s only a matter of time before these quakes bring civilization down round our ears....” A thought seemed to strike her. “Evacuation to Mars? When we haven’t even set foot on the planet yet—except for robots!”

“The President doesn’t give a thought to a trifle like that. The scientists and engineers will just have to devise something. Most people can think of something when their lives depend on it. What the World Council doesn’t understand is that it takes time to develop a massive undertaking like that.” Bob wiped his face decisively.

“To blazes with shop talk! You grab some sleep and I’ll fix up a meal. Okay?”