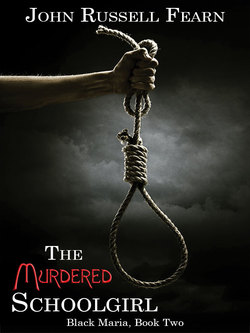

Читать книгу The Murdered Schoolgirl: A Classic Crime Novel - John Russell Fearn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Maria Black, M.A., rose to her feet from behind her massive desk as her two visitors entered. She was an impressive, strong-featured woman, gowned in black silk, with her black hair drawn into a bun at the back of her well-shaped head. From the way she stood, from the aura of mystery she emitted, it was perfectly clear that she alone was the ruler of the college.

“I am afraid,” she said, smiling, “that the porter gave me no names, merely referring to two people wishing to see me urgently.… Do come in, won’t you?”

She came from behind her desk, shook hands cordially, and nodded to two chairs. When the girl and her escort—a middle-aged man in high ranking military uniform—were seated, she returned to her seat and fingered the slender gold of her watch-chain as it glittered against her dress.

“I am afraid, Miss Black, that this visit is somewhat sudden,” the military man smiled. “I am Major Hasleigh, and this is my daughter, Frances.”

Maria’s keen blue eyes regarded her. She seemed young—perhaps sixteen—a pale-faced blonde with regular features and very wide grey eyes that appeared utterly innocent. Knowing girls, however, Maria Black reserved her judgment.

“Briefly,” Hasleigh went on, “I have had the misfortune to lose my wife and be ordered to join my unit abroad immediately. Formerly, while my wife lived, Frances here was able to have her education at a local day school. Now, however, the home is sold up and I have to depart—so I am in a pretty big predicament. I felt I must leave her in good hands, and having heard excellent reports on Roseway College—and yourself, madam—I thought I would like to hand her into your care.”

“I see,” Maria nodded thoughtfully.

She decided that he was of very uncertain age, good-looking in a way, with a face so red that he lived up to the traditional cartoons of majors the world over. His thick grey hair set him at about fifty. He had a grey moustache, too—and yet somehow his features were curiously young. Altogether he was not easy to assess.

“I’ll just fit into whatever regulations there are, Miss Black,” Frances said anxiously. “I know that it is an intrusion to burst in early in the summer term like this and expect to be enrolled but— Well, I just can’t be left alone! It was my idea really that I be sent here. I’ll not be any trouble, really!”

“The military authorities are so ruthless,” the major sighed. “I have only about twelve hours in which to turn round.”

“Quite,” Maria nodded. “I appreciate your position—and in these wartime days it behooves us to help each other as much as we can. I am willing for that reason to waive our usually strict rules. You would wish to domicile here right away, Frances?”

The girl nodded eagerly.

“Hmm.…” Maria took a syllabus from the desk drawer. “You may wish to study these terms and conditions, major, while I make inquiries as to vacancies—”

He nodded and took the folded card from her. Turning to the house telephone Maria said briefly: “Ask Miss Tanby to step along to my study, will you please?” Replacing the receiver, she glanced at the girl.

“Where have you been receiving your education up to now, Frances?”

“Elmington High School. You may not know it, though, ma’am; it is only a little place, Elmington. A Surrey village.”

“No, I don’t know of it,” Maria admitted. “I—”

“If you will excuse me, Miss Black,” Major Hasleigh interrupted, putting down the syllabus, “these terms are quite acceptable. Money is no object. As much as you require in advance, just as long as my little girl is happy and safe, as I know she will be with you.… I am telling you this before your—er—Miss Tanby arrives.”

“Miss Tanby is my Housemistress,” Maria explained, and at that moment there came a knock on the door and the pale but deadly efficient Eunice Tanby came in.

“You wish to speak to me, Miss Black?” she asked, glancing at the visitors.

“I do, Miss Tanby—on a rather urgent matter of placing a new pupil. Meet Major Hasleigh and his daughter Frances.… Miss Tanby, my Housemistress.”

Tanby smiled with colourless lips; then Maria got to her feet.

“I was wondering, Miss Tanby, if there is room in Study F in the New House for this young lady? I assigned two pupils to it only the other day—”

“Yes, Miss Black—Beryl Mather and Joan Dawson.”

“Splendid! That leaves room for one more.… Three to a study is the general rule,” Maria explained, turning. “Well, Major, that settles everything.”

“I’m so glad,” he said earnestly. “As to the terms—”

“I am sure we can attend to that most satisfactorily,” Maria interposed. “Miss Tanby, I will leave Miss Hasleigh in your care. Have her bags taken to Study F, show her the room yourself, and then I feel certain that in your own inimitable way you will make her feel at home.… Thank you for coming so promptly.”

Tanby shrugged, accustomed to abrupt dismissals. She waited while the girl took leave of her father—yet endearing though it was, Maria noted they did not kiss each other.… Then Tanby took the girl’s arm and led her from the room.

Maria sat down again, her cold eyes on the major’s face.

“I am prepared,” he said, “to pay a year’s fee in advance. It may be at least a year before I am back in England—”

“That’s very generous of you,” Maria said, “but it also raises a point which I must clarify, Major. Your daughter might be taken seriously ill—she might be injured or even killed in an air raid; or unwittingly get involved in criminal circumstances. If that should happen, to whom am I to turn?”

“Good Lord!” The major gave a start. “Air raids apart, I am sure there is no need to fear. She is a healthy girl and very quiet. As for criminal circumstances— Really, Miss Black!”

“Such things have happened,” Maria stated, unmoved. “It is one of the regulations set down by our Board of Governors. Take a small instance. If your daughter were down with double pneumonia and I had no relative to contact, where would I be?”

“I see,” Hasleigh muttered. “Well, I am not allowed to hand on my own address abroad with my unit for security reasons—but I’ll tell you what you can do!” His eyes gleamed in sudden inspiration. “In case of emergency call on my sister-in-law—Mrs. Clevedon, The Willows, Sundale, Essex. As the wife of a big financier she will have plenty of influence in case of anything—er—criminal,” he finished, drily.

“Much obliged, Major.” Maria made a note of the address. “I have to do it because in wartime—forgive me—you might never return—”

He laughed. “I’m fully aware of that. As to other matters on the financial side, just communicate with this bank and they will attend to it.”

Maria took the cheque he had written out—an account drawn on the Elmington Branch Bank, Surrey. She nodded, then said:

“I shall need your daughter’s ration book and identity card if you please. So many regulations these days, unhappily.”

“Yes, of course.” He pulled out his wallet and handed them both over. Both ration book and identity card had a new label on the front, reading—Frances Hasleigh, c/o Roseway College, Sussex.

“So you anticipated results, Major?” Maria smiled.

“I did, yes. I had Frances transfer her address the moment she thought of coming here. It was a risk—but it came off, I’m glad to say.”

Maria put the cards in her desk drawer; then as she and the major reached the door of her study, she said casually:

“Since you are liable to be away a long time, Major, perhaps you would like to carry in your memory a picture of where your daughter will work, play, and sleep?”

“Well, I—” He hesitated. “I don’t want to take up a lot of your time on account of my sentiment, Miss Black.”

“Not at all; daughters are very precious.… Just come with me.”

Maria swept out into the passageway and thereupon began a majestic parade. There was something magical about the way under-teachers, stray pupils, and occasional members of the domestic staff fell away from about her as she advanced.

In turn she took the major at a rather breathless speed to the classrooms—where a dead silence descended while she explained the finer points—then up to the long, cool Sixth Form dormitory, shaded against the blaze of the summer sun; and up again to the solarium and gymnasium, with its endless equipment for improving the physique and maintaining the health. It was in this big room, with its trapezes and parallel-bars, that the major gave a sharp glance at three instruments standing against the wall.

“Are those ultraviolet machines?” he asked quickly.

Maria nodded. “A most useful adjunct of modern science, Major, and used by quite a lot of my pupils, especially those with inherently pale skins who feel they might improve themselves by a little—hmm!—tan.”

“My daughter is never to use one!” Major Hasleigh declared harshly.

Maria raised her eyebrows. “My dear Major, it is purely a matter of personal choice. None of my pupils is forced to use ultraviolet. If your daughter does not wish to make use of the treatment, that is her own affair entirely.”

“I am worried that she may be forced into it. There is that kind of thing to reckon with among girls.”

“I presume,” Maria said, rather coldly, “that there is a definite reason for this rather—er—arbitrary request?”

“A medical one. Something she doesn’t know about.”

Maria shrugged. “As you wish, Major. I will give definite instructions of your wishes to the Housemistress and the physical instructor.… Now, shall we proceed?”

“Yes, of course.”

But for the major all interest seemed to have gone. Besides, Maria took him from place to place with such speed that he had hardly time to absorb the virtues of the swimming bath, the dining room, the chapel, and other amenities. He was quite breathless by the time he was conducted back to the steps of the main building and given Maria’s firm handclasp as his farewell.

From the top of the School House steps she watched him go across the quadrangle—then she returned to her study and sat down.

Pondering, she studied the cheque again. Finally she made up her mind and rang up the bank itself in Elmington, Surrey, and for some reason she felt quite rebuffed when she learned that the account of Major Hasleigh was completely in order.

“Extremely peculiar,” she muttered. “Maybe I need the opinion of a second person—”

Once again she summoned Miss Tanby over the house telephone, and like the slave of the lamp the Housemistress reappeared with silent promptness.

“I have had to leave the Sixth Form in the middle of its history lesson, Miss Black,” she announced anxiously.

Maria smiled. “My dear Miss Tanby, with history changing every day I am sure it will have to be rewritten anyway.… Sit down, please. I feel the need of one of our little confabs.”

“Very well, Miss Black,” Tanby answered, folding her angular figure on to a chair.

“You know, for instance, that I have the rather disturbing weakness of being in love with criminology—”

“Yes, Miss Black, I know all about your private hobby—your study of crime, your deductive capacities, your passion for the unusual.… I even remember,” she added in a hushed voice, “how you solved the mystery of your brother’s death in America last summer—calling yourself ‘Black Maria’ and enlisting the help of a—er—Bowery thug for the purpose.”

“That,” Maria sighed reminiscently, “was a truly glorious vacation, and I really did enjoy myself in the company of Mr. ‘Pulp’ Martin. However, that is behind us, Miss Tanby, and thanks to your silence no girl in this school—or the public either—knows that I solved that mystery. It would hardly do for the girls to know: they might start calling me ‘Black Maria’ to my face!”

Miss Tanby shifted uneasily.

“Tell me, Miss Tanby, what do you think of a man whose high colour smears when he gets warm?”

Miss Tanby frowned. She had never studied the colour of men very closely: they had never given her the chance. “I don’t quite understand, Miss Black—”

“I am referring to our departed friend, Major Hasleigh. There is something distinctly peculiar about that upright military gentleman! Something that arouses my suspicions.…”

“I thought he seemed a very respectable gentleman,” Tanby said timidly.

“Respectable, I grant you—but most unorthodox! I was struck from the moment I first saw him by his very high colour. It was not the pink and purple bloom of cardiac trouble, nor the brick-red or nut-brown of exposure to the elements. No, it was an odd shade of matt red, rather like the colouring matter some young ladies put on their legs in these days of stocking shortage.…” Maria coughed a little and halted. “It was utterly unnatural! So, rather at the expense of my own legs and heart, I gave him a miniature marathon round the school’s appointments to see what happened when he really became warm,” Maria smiled wickedly. “As he left I was rewarded with the amazing sight of seeing white trickles in the redness about his forehead! His colour was applied, and in places perspiration removed it. Normally I should think he is fairly pale.”

Tanby simply sat and said nothing. Maria gave her an irritated look. “Well?” she asked.

“I’m sorry, Miss Black, but I was just wondering if there is really anything significant about it. Presumably the major thinks sunburn powder makes him attractive.”

“Sunburn powder?” Maria repeated.

“Quite different from the lotion used for legs,” Tanby explained. “The leg lotion doesn’t have to smear because of rain; but sunburn powder is used very often by people with pale skins to—er—enhance their attractiveness.…” Tanby stopped as though she were astonished at her own revelations; then she added mildly, “I’ve seen the powder and the lotion both advertised.”

“And no doubt have used them,” Maria commented drily. “However, we are not here to discuss feminine frivolities or the virtues of cosmetics. What I want to know is why a military man should be so effeminate as to use such a powder. I suspect, too, that his hair was powdered, though I could not exactly blow on it to find out. So, Miss Tanby, a man with powdered face and hair and an intense dislike for ultraviolet equipment suddenly arrives and places his daughter with us, leaving a year’s fee in advance. It is, to say the least of it—peculiar.”

“Surely, then, you should have refused to take his daughter?” Tanby asked, rather bluntly.

“I could hardly do that because her father powders his face and hair, could I? He paid the fees by cheque, which I find is quite genuine.…” Maria gave a little sigh, “I suppose that I am so accustomed to looking for peculiarities in people that I am making a mountain out of a molehill.… All the same, I would like to know why he doesn’t wish his daughter to undergo ultraviolet ray treatment at any time. It is such a stimulating process, too. There have been times when the girls have been in class when I have myself— Hmm, we have no need to go into that.… You will see to it, Miss Tanby, that the girl does not have the treatment if you can prevent it, and if any of the girls try and make her, she is to report it to me.”

“Yes, Miss Black,” Tanby nodded.

“Thank you for listening to my little—er—investigative talk. I find you a great help at such times. Amongst other things, keep your eye on this girl Frances. If she proves as unique as her father, she will be well worth watching.”

Tanby waited, then seeing the imperious nod of the hair bun she went out silently.… Alone again, Maria’s thoughts were not on the biology class she was due to take at three o’clock. They were on the address of Hasleigh’s sister-in-law, which she had scribbled down.

“Prominent financier,” she mused. “I wonder if prominent enough to be in Who’s Who?”

Evidently not, for all her searching failed to reveal any trace of the name. It seemed reasonable enough that a house with such an impressive address should have a telephone, anyway, so she dialled inquiry and asked for the number. Politely she was advised that “The Willows, Sundale, Essex,” was not listed.

“Extraordinary!” Maria muttered, “or is it?”

She turned next to her index of British schools, but she failed to trace the girl’s previous seat of learning—Elmington High School. Small the place might be, but every college and school in the country was included here, as she well knew.

“Maria, you are learning things,” she muttered. “Out of nowhere, literally, you’ve got a new pupil. Maybe Major Hasleigh handed to me what the films call a—ah—‘bum steer,’ so he could get out without evading my questions. However, there are other ways yet.”

Accordingly she sent a telegram to the sister-in-law over the phone, reading— Are you relative of Major Hasleigh? Reply to Black, Roseway College, near Langhorn, Sussex. Then, satisfied that she had done all she could for the moment, she hurried off to take the biology class.

The girls, however, found that their empress was right off her form. She even muffed that technical bit about the sub-clavicle artery, which was her favourite bit of bonework. They little knew that her eyes and mind were trained on the school gates, through the big classroom window, otherwise they might have understood.

When the telegraph boy did eventually appear Maria had moved on to the Fourth Form. She brought the lesson to a hurried close, then hastened to her study just as the porter was bringing the telegram in. She took it from him, dismissed him briefly. Then when she had the buff form in her hand, she frowned over it.

It had a blue ink rubber-stamp right across it—

UNDELIVERABLE. ADDRESS UNKNOWN.

“Extraordinary, even incredible,” she reflected. “A girl from nowhere, indeed, whose associations seem to have melted like her father’s sunburn. Definitely I must keep an eye on her—definitely!”