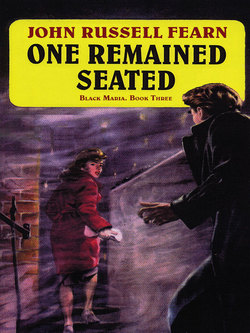

Читать книгу One Remained Seated: A Classic Crime Novel - John Russell Fearn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The man in the ill-fitting grey overcoat and with a slouch hat pulled well down over his eyes might have been alone in the railway compartment for all the attention he paid to his fellow-travellers.

He was preoccupied with his own thoughts, tracing backwards through fifteen years. His body was freed at last from implacable walls and iron-hard routine, but not his mind. It insisted on lingering in the circumscribed area of a prison cell. Even now, speeding away from it on this rickety, noisy train, he could still feel the cold walls that had hemmed him for so long.

With a squeak and a rattling of doors the train stopped, shattering the countryside with a volcanic outburst from its safety valve. The man in grey lurched to his feet, took down a cheap suitcase from the rack, and then opened the door. He stepped out into a cold, bracing wind, wavering station lights, and the clangour of milk cans. Far away a voice was mournfully wailing “Lang’orn! Hall change for Lex’am!”

Feeling for his ticket, the stranger walked towards the exit barrier. He was revealed now as tall and heavy-shouldered. His face was powerful, with a strong, ugly mouth, long, pointed nose, and bushy eyebrows. Handing in his ticket to an inspector at the barrier, he asked:

“Where’s a good place to stop for a day or two?”

“Might try the ‘Golden Saddle’, sir. Not bad. Straight up the ’igh Street there.”

“Thanks,” the other said briefly; then with a sudden squaring of his shoulders, like a man who has much to do, he turned to face the fitful lights which bobbed along the vista outside the station entrance.

Langhorn was an agglomeration of ill-assorted frontages, of shops that were unashamedly converted houses, of higgledy-piggledy roofs and badly planned forecourts jutting out on to the pavement to snare the unwary.

Here and there, however, modernism had arrived. It showed itself in a closed snack bar sandwiched between two old buildings; it was revealed again in the façade of a cinema. The stranger noticed that the hotel he sought was anything but modern, even though it had a clean, inviting aspect. His attention swung back to the cinema directly facing it across the narrow street.

The cinema’s entrance way was marked by two rotund pillars of white tiling supporting a red canopy. The place called itself LANGHORN CINEMA in red stone cubist letters over the entrance. Postwar fuel regulations forbade neon outside, but beyond the glass doorway in the foyer, lilac tubes flickered in and out attractively and spasmodically illuminated the placarded features of Hedy Lamarr.

As yet it was only half-past six and the cinema was not open to the public. It possessed no sign of life at all except for the ginger head of a girl just visible through the grille of the advance-booking office. It was cunningly imbedded in one the huge side pillars, and so was set beyond the doors and almost on the street itself.

The stranger hesitated. For some reason the place had an uncommon fascination for him, so much so he walked up the four pseudo-marble steps and looked into the foyer intently through the glass barrier.

Looking out onto the chilly night from the warmth of her cashier’s box, Mary Saunders saw the stranger’s dogged, putty-grey face in profile, illuminated ever and anon by the neon. He looked forbidding, and she decided he looked as though he had walked out of the thriller serial that the cinema screened every Saturday afternoon.

The stranger stood peering, gripping his cheap suitcase. Though the foyer was empty, he seemed to be looking longingly for somebody or something.

At last Mary Saunders could stand it no longer. She raised the glass slide before the grille bars and peered out into the draughty street.

“Anything I can do for you, sir?” she asked politely.

The man descended two of the steps and stooped to look to look at her through the gold-painted filigree. “What time do you open, miss?”

“Half-past seven, sir—and the performance starts at quarter to eight, finishing at ten o’clock....”

“It doesn’t matter when it’s over.... Look, that poster on the foyer there—next to the picture of Hedy Lamarr. It is advertising Lydia Fane in Love on the Highway. Is that on now?”

Mary pointed up through the bars of her cage to the underside of the canopy. “It’s advertised up there, sir, on the streamer....”

The stranger looked above him at a lengthy oblong board painted green along its borders and suspended by chains. It swung to and fro in the cold wind, and a long paper sheet within it advertised Lydia Fane in gigantic letters with Love on the Highway in a small scroll beneath it. As yet, with the canopy lights off, it was not immediately visible from below.

“Starting tonight, sir,” Mary explained. “Runs tonight, Tuesday, and Wednesday.”

“Can I book?”

“Certainly, sir—Circle only, though. We block-book the Stalls for regular patrons....” Her slim arm went up to the charts out of the stranger’s view.

“Circle will do,” he decided. “I want the best seat in the front row for tonight, tomorrow, and Wednesday night....”

Mary Saunders blinked. Then she drove the point of her blue crayon through seat A-11 on the charts for that night, the next, and Wednesday. Skilfully she thumbed the ticket-blocks and then handed three tickets under the goldwork.

“Seven-and-six, sir, please.”

Without a word the stranger planked down three half-crowns. “Do you have matinées?” he asked, as he took up the tickets and prepared to go.

“Every day except Monday, sir.”

“Thank you, miss.”

He picked up his case, looked once more at the streamer under the canopy, then began to walk across the road towards the ‘Golden Saddle’.

That same evening, still in his grey coat but with his hat resting on the plush balustrade in front of him, he watched the programme through with that immovable fixity which seemed to be a habit with him....

And the following evening at precisely the same time, he was once more in A-11 in the centre of the row. This time the usherette in charge of the Circle remembered him from the previous night, and wondered to herself what anybody could wish to see twice in such an indifferent programme.

* * * *

Frederick Allerton always left home for duty at the Langhorn Cinema with a profound sense of the responsibility ahead of him. Maybe his comparative youth—he was twenty-one—caused him to magnify his position out of all normalcy, but it did at least make him extremely conscientious. As the chief projectionist of the cinema, he took pride in the fact that everything depended on him, that the smiles or curses of the patrons would in the main be the outcome of his control. And in his five years of employment, creeping up from lowly rewind-boy to chief, he had shown himself ambitious, a clever electrical engineer, and at times an excellent showman. His key-job and low medical grade had kept him at his post, a diligent controller of the whirring, hot machines that plough through miles of celluloid, different and indifferent.

At six-forty-five precisely on this Wednesday evening he took his usual farewell of his parents, buttoned up his overcoat, and went out through the kitchen into the back garden. Cold wind under icy December stars smarted his cheeks as he tugged his bicycle from the outside shed. He threw one long leg over the saddle and rested his foot on the pedal. With the other foot he pushed himself along until free of the pathway up the side of the house—then he went sailing illegally down the pavement to his favourite dip in the kerb and so out into the road.

With a whirr his homemade dynamo came into being and cast a fan of radiance on the asphalt of the quiet suburban road ahead of him. To his rear the red companion light glowed in baleful warning. He was rather proud of his dynamo, as he was of all his electrical handiwork, but it troubled him that the damned thing had developed an obstinate flicker. Now and again it would go out and leave him pressing against searing wind and darkness—then back the light would come with exasperating brilliance. Still, he knew the way blindfolded: the only worry was the possibility of the police happening on him at the wrong moment.

To reach the centre of Langhorn he had two miles to cover, and he usually reckoned to do it in exactly ten minutes—longer if the wind was against him. Tonight it was against him all the way, and he pedalled with his head down against it, cursing under his breath.

Eleven minutes after leaving home he reached Langhorn High Street, but beyond a brief glance ahead he did not bother to survey it thoroughly. It was dark now, anyway, as far as the shops were concerned. The only light came from the lamps edging the kerb at needlessly wide intervals and the canopy globes of his destination.

Stubbornly he pedalled onwards, preparing for a sharp right turn when he neared the cinema.... Then the dynamo went off again. He threatened it savagely, reached down with one hand to bang the dynamo against his front wheel—then all of a sudden he was knocked off his saddle and landed somehow with the bicycle round his legs. Near him somebody was floundering in the road and cursing him fiercely.

“You—you damned idiot! Why didn’t you have a light on...? God! My leg.”

Aided by his youth and long thin body, Fred Allerton was quickly on his feet, vaguely aware of a tingling knee as he helped to raise a heavily-built man in a grey overcoat and slouch hat.

“Idiot!” the man repeated, rubbing his leg. “You might have broken it.”

“Evidently I didn’t, though,” Allerton said cheerfully. “You see, my dynamo doesn’t always work as it should. I never even saw you....”

“It comes to something when a man can’t step off the pavement without a blasted cyclist knocking him flying. No light—no bell. I’ve a good mind to tell the police about this.”

“All right, if you want to get awkward about it!” Allerton could be very short-tempered sometimes. “You can find me at the Langhorn Cinema. I’m the chief projectionist.”

The man in the grey overcoat looked at him for a moment; then without another word to signify his intentions, he walked off towards the pavement, heading in the direction of the ‘Golden Saddle’ hotel. Allerton watched him, then after a guilty look about him he trundled his somewhat lopsided machine towards the cinema, raising the cycle on his shoulder as he walked up the steps.

“Who were you rowing with?” asked Bradshaw.

Bradshaw was the doorman, though there had been occasions when the more select patrons had called him a commissionaire. It was left to the insensitive cinema staff to tell him what he really was. To the public he was merely a big, six-foot man with shoulders widened by the epaulettes on his bottle-green uniform. His face, red by nature, had an almost fiery tint through constant exposure to the winds that chose the High Street as their sporting ground. Blue eyes, inflamed round the edges with grit, gazed with disconcerting fixity from under the gleaming peak of his cap.

“I was rowing with an idiot,” Allerton answered briefly, pushing through the little assembly of people awaiting the cinema’s opening. “Anyway, how did you know?”

“I ’eard you shouting, of course. Wind’s that way tonight.”

Allerton grunted, eased the bicycle from his shoulder, then entered the foyer. Mary Saunders looked round the door of her cage and called a greeting. But Allerton ignored her. He was in a bad temper and his knee hurt. And that nosy-parker doorman would have to be outside four minutes before his usual time....

Allerton dumped his bicycle in the disused sweet-stall near the stairway leading to the Circle and closed the imitation bronze door upon it. He tugged off his overcoat and hat, releasing an untidy mop of brown hair that had become wiry through the influence of static electricity—then he headed for the manager’s office. But the manager had not yet arrived. The door marked PRIVATE was firmly locked.

With a shrug Allerton turned back to the Circle staircase with its soft, luxurious carpet—then he paused as Nancy Crane came hurrying down with her black silk frock billowing a little from her shapely legs. Allerton admired them silently as she came down to his level.

“Where’s the boss, Nan?” he asked her.

“How should I know if he isn’t there?” Nancy Crane had the oddest way of mixing her words, but she did it so disarmingly that nobody objected. She was small, dainty, with blonde hair and delicately reddened lips. Her very blue eyes made Allerton’s young heart skip a beat every time she looked at him.

“I only asked,” he said defensively.

Nancy felt the golden curls at the back of her head with a slender hand. “Anyhow, is that any way to greet your fiancée?”

“Sorry, Nan.... I’m having a bad evening.”

Nancy’s blue eyes regarded him. He certainly looked morose, more so by reason of his rather high cheekbones, sombre dark eyes, and drooping comers to a large mouth.

“Oh? What’s caused it?” she asked.

“I knocked a man down with my bike. If he reports it, the police will summon me or something. You know how the boss is about things like that. Smears the reputation of the cinema. I might get fired!”

“With labour so short it isn’t plentiful? Not a bit of it! You didn’t give your name to the man you knocked down, did you?”

“No. But I told him my job and where to find me.”

“The things you worry over!” Nancy murmured, inspecting herself in the bevelled mirror embedded in the wall by the staircase. “I wouldn’t!”

Nancy Crane had no need to expect trouble anywhere. She was pretty enough to get whatever she wanted from almost any young man—and what was more, she knew it. But she had plenty of sense as well as above average looks, which was one reason why she looked forward to becoming Allerton’s wife. Better than anybody, except his parents, she knew his worth.

“Tell the boss I was going to ask him about tomorrow’s programme,” Allerton said, starting up the stairs. “It’s Wednesday night, remember, and if the film transport doesn’t come within the next hour, he’ll have to ring the renters.”

“Okay, I’ll tell him,” Nancy promised, and devoted herself to getting her hair to her liking....

* * * *

Within the disciplined quiet of Roseway College for Young Ladies, Miss Maria Black, M.A., the Principal, sat studying the evening paper. Her pupils, had they been able to look over her shoulder, would have been surprised to find the Langhorn Times open at the amusement section.

“Love on the Highway.... Hmmm!”

Maria Black put the paper down and fingered the slender gold watch-chain gleaming against the black satin of her dress. Her strongly cut, expressive face was pensive—yet somehow irritated.

“Just where are all the gangster films these days?” she mused presently. “I could have sworn that Death Strikes Tomorrow was showing at the Langhorn. Maybe I confused it with another cinema. Love on the Highway indeed! Lydia Fane? Never heard of her.... Yet one must do something for a change, and no other cinema seems to have anything appealing.”

She rose and began to pace the warm study slowly. To Maria Black the problem of finding the right picture to visit was just as intricate a business as solving a mystery; and at both she could claim distinction. It annoyed her, though, to find that her love for a crime picture was unrequited this Wednesday night.

Coming to a decision, she pressed the bell-push. By the time the bloodless housemistress, Eunice Tanby, had come into the study, Maria Black was dressed in a severe but smart hat, a heavy camelhair coat, and was putting her umbrella on her arm.

“Ah, Miss Tanby! You will be good enough to take over for a couple of hours. I have decided that I shall relax at the Langhorn Cinema. It’s my last opportunity to see Love on the Highway.”

“Yes, Miss Black,” Tanby assented colourlessly.

“Say it,” Maria invited dryly. “What do I want to see such a picture for? Frankly, I don’t—but one must have a change. And you know my private passion....”

“Yes, Miss Black. Crime—crime films—or just films.”

“A very apt summing up,” Maria approved; then she swept out of her study and up the corridor to the outdoors. In five minutes she boarded the Langhorn bus that rattled its way between Roseway College and Langhorn Square.

The bitter wind was gusting as she descended in the town’s main square. Pushing against it and half closing her eyes against whirling dust, she made her way slowly up the High Street, keeping well within the shelter of the closed shops for protection. She was wondering why she had chosen such a vile night to visit a very mediocre picture.... Then the sound of voices made her glance up. She paused, puzzled for a moment by a dim, unexpected vision in the roadway ahead under a street lamp.

“...I’ve a good mind to tell the police about this!”

“All right, if you want to get awkward about it. You can find me at the Langhorn Cinema. I’m the chief projectionist.”

Maria began walking on again, watching as the distant tangle sorted itself out into two men facing each other—the one big and burly in a light-coloured hat and coat, the other the tall, spare figure of Fred Allerton. Maria knew him well enough by sight and smiled to herself.

“Frederick getting himself into trouble again, apparently,” she murmured. “A good man at his work from what I hear, but just a trifle too impetuous....”

By the time she had moved another five yards the two men had separated—the big man towards the ‘Golden Saddle’ hotel and Fred Allerton into the entranceway of the cinema. As Maria walked up the cinema steps and waited by the glass doors for them to be opened, she saw Allerton in the distance of the foyer beyond talking to Nancy Crane.

“Nasty night, Miss Black,” observed the doorman.

“Decidedly cold,” Maria agreed. “One expects little else in December, however. I notice, my man, that Lydia Fane is billed as the star of this picture tonight. I am a fairly keen—hmm!—film fan, but I do not recall ever having heard of her!”

“Nor me, mum, but the boss says she’s a star and he’s fixed the publicity that way, so there it is. What I’ve seen of the film—nippin’ in between times, as you might say—it’s rank.”

“That’s his polite way of putting it, Miss Black,” Mary Saunders remarked, peering out into the night through her prison bars. “I’d suggest you to go back to the school.”

“Such bad salesmanship!” Maria reproved, smiling. “Never turn patrons away, Mary!”

“But you’re more than a patron, Miss Black: you’re pretty nearly an honoured guest. It’d be a shame to take the money.”

Mary sat down again behind the grille and only her ginger hair was visible. Other people were collecting rapidly now, forming a small queue down the steps. At last Bradshaw received the signal from inside the foyer and threw the doors open wide.

Winter and Maria swept into the foyer together. She stopped at the ordinary booking office with its big sign over the top—STALLS ADMISSION BY BLOCK BOOKING ONLY. Behind the gilded grille sat plump Molly Ibbetson, ponderous but thorough, her shining black hair a curious mixture of waves and curls.

“Evening, Miss Black,” she said pleasantly, her full-moon face with its rouge-and-powder effects breaking into a smile. “Your usual Circle ticket?”

“Thank you, Molly—if you please.”

Maria took it and then proceeded majestically on her way through the foyer. Just as she neared the Circle staircase, the manager came out of his office at the base of the stairs and closed the door behind him decisively.

Gerald Lincross was not just the manager of the Langhorn Cinema; he was the owner as well. A man in his late forties, he was to his patrons merely the medium-sized smiling man with the half-bald head who welcomed them in—and out—in his faultless dress suit and crackling white shirt front and collar. His remaining hair was black and curly, while his features were somewhat pointed and the mouth flat, seeming more so because of false dentures which fitted too far back. Always he was smiling, always deferential, with concern for the welfare of his patrons—regular and casual—always peeping out of his round and somewhat childlike blue eyes.

“Good evening, Mr. Lincross,” Maria greeted him, pausing.

“Why, Miss Black....” He came and shook hands with her. “How are you? Chilly weather, eh? To be expected, near to Christmas.”

“Yes,” Maria agreed, then she changed the unoriginal conversation. “Frankly, Mr. Lincross, I am not intrigued by your choice of a film for the first half of this week. Love on the Highway sounds like a filler to me. I could have sworn I saw an advertisement for Death Strikes Tomorrow.”

“You did,” Lincross acknowledged, smiling. “It should have been here for Monday, yesterday, and tonight, but at the last moment the renters changed it. Just one of the trials of the business, you know. I’m making do with Love on the Highway, and I expect I shall hear about it from my patrons—if they are as observant as you, that is.”

The patrons were now coming in steadily. As they streamed past to Stalls and Circle, Lincross inclined his shoulders back and forth like a mechanical doll and wore a permanent smile.

“Well, Mr. Lincross, I will leave you to your duties,” Maria remarked.

He did not answer. His attention had apparently been caught by a big man in a grey overcoat and soft hat coming in through the main doorway with a little swarm of people in front of him. He was tall enough to be visible over the heads of the people preceding him.

Suddenly Lincross turned and noticed that Maria had raised one eyebrow at him questioningly. “Forgive me, Miss Black,” he murmured. “Just a thought that occurred to me.... I must see Miss Thompson immediately.”

He bowed briefly to her then hurried to the doorway leading into the Stalls. Maria shrugged to herself and started the long climb of the Circle stairway. Halfway up, where the stairs took a sharp left-hand turn, was a polished door marked STAFF ROOM ONLY—PRIVATE. Maria went past it to the left where yet another private door leading to the projection-room was sunken into the wall. So she continued up the last flight of stairs into the Circle.

“Good evening, Nancy,” she greeted, as the pretty blonde girl tore the admission ticket in half. “Still on the treadmill, I notice.”

“A girl must live,”’ Nancy observed, with uncommon philosophy, then reached for the ticket of the man following Maria.

She went across to her usual seat in the third row from the front, left block, and settled herself with her umbrella standing up beside her, her right hand clamped firmly on its handle. As usual her attention was centred on the incoming people.

A friendly buzz of conversation, unintelligible but distinct, made itself apparent over the Sousa march thumping from behind the green-and-gold curtains covering the screen. Floodlights of amber and mauve flickered across those curtains, worked most dispassionately—had the audience but known it—by a spotty youth in overalls in the projection room.

Smoke rose in increasing density to the ventilator grille stretching across the gently arching ceiling. It was a very wide ventilator, painted yellow to imitate gold and the filigree designed in diamond shape. It stretched from wall to wall like a gilded chasm in the roof. Farther away, over the area occupied below by the Stalls, were two smaller ventilators, circular and perhaps two feet in diameter. Behind them fans whirred to suck out foul air....

Maria lowered her eyes from an absent survey of the ventilators to a big man in a grey overcoat and soft hat. He walked slowly down the white-edged steps to the front of the Circle, took his half-ticket from Nancy Crane, and then lumbered along to the seat in the exact centre of the row—A-11. With a clatter the risen people on the row sat down again, and the big man took off his hat and laid it carefully on the plush-topped rail in front of him.

Beyond noting that he had thinning grey hair and a face, in profile, of uncommon strength, Maria paid no more attention to him, though back of her mind she remembered that she had seen him coming in at the foyer doorway. Not that it signified, only...well, he was different, somehow, and possessed such an air of power and sombre purpose.