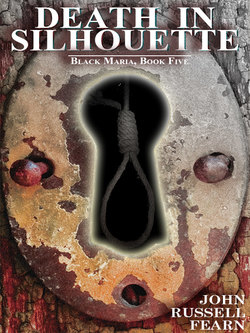

Читать книгу Death in Silhouette - John Russell Fearn - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

Suddenly, as she stared at the wall and the shadow of the hanging figure, Pat Taylor gave a hoarse shout that rose into a scream.

“It’s Keith! He’s gone down there and—”

“Back!” her father snapped, stopping her from hurling herself forward down the wooden staircase. “Get back, all of you! There’s something horrible here.…”

He forced them away by main strength and closed the door. There was perspiration gleaming on his plump face. The eyes of the Misses Banning and Andrews were round in horror. They had only glimpsed but they had seen enough. It was probably sheer terrified wonder that kept them on their feet. Pat who had apparently guessed the truth, turned suddenly grey and fainted. In a moment her mother was fussing over her, half-dragging her away from the little group in the hall.

“Get the doctor,” Mr. Taylor snapped suddenly to Gregory. “Hurry up, lad.”

“Okay—and the police?”

“I—I don’t know—”

“I do!” Gregory said, suddenly calm with his legal mind ticking over smoothly. “It looks to me like plain suicide, but it could be murder.… I’ll call the police, too,” he decided, and dived for the front door.

“Keith!” Ambrose Robinson whispered, staring dazedly after Gregory as he dashed down the front path and left the door open. “He’s—he’s hanged himself! Hanged himself! If it is him.… But it must be! I’ve got to see him—”

“Better let me do it,” Taylor said grimly. “No job for you, he being your son.”

Ambrose Robinson hesitated and Mr. Taylor suddenly became the captain of the ship.

“Get back in the front room, all of you,” he ordered. “I’ll attend to Keith. After all, this is my house. Mother, get these two girls to help you with Pat.…”

He opened the cellar door again and swung it to behind him as he hurried down the steps. Those in the hall had hardly got into the drawing room with the unconscious Pat before Gregory came speeding back. He dived straight for the cellar door, pushed it to after him, since the lock was half off, and then hurried down the curving staircase. On the wall his father’s shadow had been added to that of the hanging figure. His father’s arm was working vigorously.

Gregory hesitated for a moment, shocked out of his usual cold reserve. His father was standing on the solitary backless chair that was the only piece of furniture in the basement. Keith Robinson was hanging from the massively thick central beam crossing the ceiling. In the beam was a rusty staple and to this had been securely knotted the clothes-rope from which the body was swinging

“For heaven’s sake, boy, give me a knife!” Taylor panted. “These knots are too tough for me.”

Gregory handed his penknife up, the blade open. His father sawed through the rope frantically and the strands finally gave. Between them they lowered the dead weight to the floor and tugged free the slipknot that had been drawn with savage tightness about the neck. The flesh of the neck was severely abrased. Keith’s eyes were staring, his tongue was lolling out. His face had turned a deep purple.

“This is awful, Dad!” Gregory whispered. “What on earth possessed him to do ir? Is he—?”

“Yes—he’s dead.” Taylor lowered the limp hand and tightened his lips. There was a look of utter wonder nore than horror on his sweating face, “Have to wait for Dr. Standish.”

“He’ll be here any minute,” Gregory said. “And the police too. In any case, Dr. Standish is the police surgeon, so it’s all the same.”

“Why—the police?” Taylor asked, speaking with effort.

“It’s suicide, isn’t it? Keith mightn’t have been dead, and in that case he could have been charged with felo de se. It might even have been murder…but don’t ask me how.”

Mr. Taylor got to his feet. Gregory did likewise. Mr. Taylor studied the cellar thoughtfully and looked up at the rope he had cut. Then he glanced at the wall.

“He used the clothes-rope which was hanging there,” he said slowly. “Then he must have stood on the chair, kicked it away from him, and—that was that. I found the chair overturned.”

Gregory looked as if he were trying to get his legal mind into focus. His father glanced up towards the doorway as there came sounds on the front path, echoing heavily at this depth. He heard the front doorbell ring. Hurried feet. Mr. Taylor moved forward to look up the curve of the staircase and saw a plump little man with a black bag hurrying down it.

“Afraid you’re too late, Doctor,” Mr. Taylor said quietly; and to Gregory he added, “Get upstairs, Greg, and tell them all what’s happened. And do it gently. They’ll have to know the facts.”

Gregory returned swiftly up the staircase, closing the door at the top. Without a word Dr. Standish—who had been present at the births of both Gregory and Pat—went down on one knee and examined the body carefully. Taylor stood waiting and watching.

“Yes,” the medico said finally, rising and dusting his knees. “Strangulation all right. The neck shows it, too. Apparently no bruises or other marks.… You’ve advised the police, Mr. Taylor?”

“They should be here at any moment.”

“They won’t particularly approve of your having cut the body down,” the doctor said.

“Won’t they?” Mr. Taylor laughed shortly. “Good God, what was I supposed to do? Let him hang? There might have been life in him. We could perhaps have saved him.”

“You should have tested his pulse first.”

“I was too confoundedly staggered to think of a thing like that.… This is the most horrible thing I’ve ever witnessed. He must have come down here, locked himself in, and then hanged himself. Right in the middle of celebrating his engagement to Pat, too!”

“Oh?” Dr. Standish shook his head. “Mmm, that is devilish, and no mistake—”

He stopped talking and turned his face expectantly. There was a pounding from the front path, the ringing of the doorbell, and then voices. In a moment or two the uniformed figures of Superintendent Haslow and Sergeant Catterall of the local police force came in view.…

* * * *

Maria Black was considerably astonished upon arriving in Cypress Avenue to behold an official police car outside the gate of No. 18, the house she wanted. She was so absorbed by the sight she nearly forgot to jam on the brakes, and stopped the Austin Seven only a couple of inches from the police car’s rear bumper. Then she sat gazing at No. 18. There was no policeman visible, except the one in the peaked uniform-cap at the wheel of the car. She did notice, however, as she moved her gaze round, that faces were peeping through lace curtains in the other houses, and that children were watching from a safe distance.

“Extraordinary,” Maria muttered, but she could feel her pulses tingling all the same. She felt like an old fire-horse which has heard the bell. Of course, the whole thing might be a coincidence. It did not say that anything was wrong in No. 18 just because a police car had parked outside it.

“Stop such idiotic conjectures, Maria!” she reproved herself. “Find out what is transpiring.”

She considered herself in the driving mirror, removed the oil-moustache from her upper lip, then climbed out of the car. With slow dignity she walked the few steps along the pavement to the police car and looked in on the waiting driver.

“Tell me, officer, is there anything—er—wrong at No. 18?” she questioned.

“The Super and Sergeant are in there, madam. A suicide, I understand.”

“A suicide?” Maria’s eyebrows rose; then she recovered her dignity, gave her costume a gentle pat, and turned to the gateway. Her ringing at the front door brought the sergeant to open it.

“Yes?” he asked, with perfect respect, and met a steady look from ice-blue eyes.

“I am Miss Black,” Maria stated calmly. “Miss Taylor is expecting me.”

The sergeant seemed to be aware of this fact. He nodded and stood to one side, motioning Maria into the hall. From here she was conducted into the front room. She came into an atmosphere still heavy with tobacco fumes. Three pale-faced young women were seated on a chesterfíeld; a youngish man with polished dark hair was in an armchair; a man like a vulture was standing with his hands clasped behind his back and his head bowed. A Superintendent of Police was considering something as he stood opposite a stout blonde woman and a good-natured-looking man.

“Miss Black!” the centre girl on the chesterfield exclaimed, and came hurrying over. “Oh, thank heavens you’ve arrived…! Something—something terrible’s happened!”

Maria did not say anything. She merely patted Pat’s arm gently. It was plain to see the girl had been crying, that indeed she was in an excitable condition, which on the least provocation might dive into hysteria.

“It’s Keith,” Pat hurried on. “That’s the boy I was engaged to. I told you about him in my letters. I—”

“Miss Black!” exclaimed Mrs. Taylor, turning—and for a while Maria found herself in the midst of hasty introductions. She could see clearly that she had arrived at a moment when formalities were purely perfunctory, when everybody was thinking not of her but of the tragedy that had occurred.

The Superintendent came forward. “I think I have all the details now,” he said briefly. “Thank you. You’ll all be summoned to the inquest. The ambulance will be here shortly—to convey the body to the mortuary, where the coroner can inspect it.… The Sergeant will stay by the cellar door until the ambulance has been, then he will go too.” The Superintendent paused, looking at Maria. “Good afternoon, madam. I understand you are a friend of the family, not a relative?”

“Exactly so, Super,” Maria conceded, her eyes straying to the forgotten sandwiches and empty glasses on the big dining table.

“You were intending to attend this—er—party?”

“I was. If you wish to know why I didn’t, I would suggest you get in touch with the owner of a two-seater having the licence number HK—four seven one. That owner will confirm that I had a breakdown.”

“I hardly think that will be necessary, madam, but thank you just the same.… You are most observant.”

Maria smiled. “So I have been told. I also believe in taking precautions. I understand that a suicide has occurred: if you should have reason to doubt suicide, you will naturally check the alibi of everybody in and out of the family. There you have mine.”

“Er—thank you,” the Superintendent acknowledged, and cleared his throat; then he turned and left the room.

There was silence, the deadly, stunned silence of inability to focus on the thing that had happened. It was broken by Ambrose Robinson muttering to himself.

“‘Oh that my grief were thoroughly weighed and my calamity laid in the balances together, for now it would be heavier than the sand of the sea.…’ Job.”

Maria considered him with a concentrated gaze, then she gave a prim little cough.

“I—er—seem to have arrived at a terrible moment,” she said quietly.

“Yes.…” Mr. Taylor looked at her moodily from the other side of the room. “Yes, you have, Miss Black. But be that as it may I don’t consider we would seem disrespectful if we made you welcome. Won’t you please sit down?”

“I’ll make you some tea,” Mrs. Taylor said, as though she hardly realized what she was saying.

“Later,” Maria said, seating herself. “I can see that you are all much distressed. I—”

“If nobody minds,” Madge Banning said, jumping up suddenly with a deathly pallor on her face, “I’ll be going home. I—I don’t feel too well. ’Scuse me, won’t you?”

She dashed from the room and swept the door shut behind her She had hardly gone before Betty Andrews made a similar excuse. Ambrose Robinson, standing by the window, saw both girls flee down the street. He turned a gaunt face. The tragedy had left him hollow-eyed, his lips working spasmodically.

“I think, if you’ll forgive me, that I’ll follow the example of those two girls,” he said. “I just couldn’t stay here and watch them remove my boy.… I must go home—be alone—offer a prayer for him.…”

His voice tailed off as nobody spoke. He left the room. Maria slanted an eye towards the window and watched his tall figure go down the pathway; then she looked back into the room. Mrs. Taylor shifted uneasily and said again that she ought to make some tea—but she did not move.

“Perhaps,” Maria said at last, “I had better go on to my hotel and return here again later when you have had a chance to calm yourselves. This is hardly the time for entertaining a guest.…”

“Hotel?” Pat repeated absently. “What hotel?” With an effort she came back to life. “But aren’t you staying with those friends of yours, Miss Black? You have friends in Redford, haven’t you?”

“I did have, my dear. They left long ago. Since you were kind enough to invite me to your celebration, I was determined to accept. So I made arrangements to stay a day or two in this part of the world, survey the local points of interest, and meantime put up at the Grand Hotel.”

“But you can stay here!” Mr. Taylor exclaimed. “Why on earth didn’t you tell us your friends had left?”

Maria smiled faintly. “I am a most independent person, Mr. Taylor. I like hotels because if I do not approve of the service I can say so. One cannot in all courtesy deal with one’s friends in that fashion.” Maria observed that her deliberate effort at conversation had somewhat broken the iron spell. “I’m so sorry I was late. As you heard me tell the Superintendent, my car broke down. Do I understand that the young man you called Keith…committed suicide?”

“I was to marry him,” Pat said dully. “I told you so in my letters. I wanted you to meet him—get an idea what you thought of him.”

“Would that have mattered so much?” Maria asked.

“I don’t know. But that’s why I asked you here. He was such a queer chap in some things. I’d have been glad of an outside opinion; but naturally it doesn’t matter any more.”

“Forgive me, but—what happened?” Maria asked. “After all, I haven’t the remotest idea.”

Her question banished the last traces of the spell and all four Taylors started talking at once. They slowed up for a while as the ambulance arrived and the body was removed—the sergeant announcing that he was going with it—then the moment the front door had closed the talking resumed.

There was excitement in the voices now, each having his or her own version of what had happened. In the middle of it all Mrs. Taylor remembered her decision to make some tea—and did so. In due course Maria found herself with a cup of tea and a plateful of sandwiches on the table beside her.

“Extraordinary,” she admitted at last, frowning, and she nodded a prompt response as Mrs. Taylor inquired if she would care for more tea. “Instead of coming to an engagement celebration, I come to the suicide of the prospective bridegroom!”

“It seems to me such an illogical thing!” Mr. Taylor declared, his fists working. “I still don’t understand it. Why should any young man suddenly decide to hang himself in the middle of celebrating his engagement? No reason! No motive!”

“I think there was a motive,” Pat said suddenly, and she was very tense and hard-eyed. “Sudden jealousy! It got him down!”

Her father looked astonished. “Sudden jealousy? Of what?”

“Remember you bringing up the matter of Billy Cranston and Cliff Evans? My two boyfriends?”

“Yes, but— Good heavens, Pat, that was only in fun! There was nothing in it.”

“Not to you, or me—not to any of us except Keith.” Pat gave a quick gesture. “He tackled me twice about the other boys I know, and his jealousy of them amounted to rage. I do believe your mentioning them must have done something to him and—and so he made up his mind to kill himself.”

“Doesn’t sound very convincing to me, Sis,” Gregory said. Judging from the expression on his lean, sallow face he had been thinking hard.

“But, Greg, there couldn’t have been any other motive,” Pat argued. “Keith was healthy—or at any rate he seemed to be—and we were going to be married. He had everything to look forward to. Only his being overwhelmed by sudden jealousy could possibly account for his behaviour. It perhaps…unhinged his mind, or something. He was a bit funny sometimes,” Pat added, frowning reflectively.

“Funny?” Maria repeated.

Pat nodded. “Yes. He was a prey to sudden moods. One moment he’d be on top of the world, and the next he’d be down in the doldrums. Sort of unstable.”

“Mmmm.…” Maria mused for a while and then she got to her feet. “Well,” she said, “the last thing I wish to do is to become involved in this tragic business, or foist myself upon you at such a time. I think it would be best if I went along to my hotel, carried out my programme of sightseeing in the next few days, and then return home. You can be sure you all have my deepest sympathy.”

Pat said urgently, “Miss Black, you don’t think I’m going to let you walk out like this, at such a time, do you?”

“Meaning what, my dear?”

“Meaning that you’re a wonderfully understanding person. I always used to come to you when I was in trouble at school: I want to do it now.”

“That was many years ago,” Maria answered, smiling. “You have your mother and father. I am no longer your temporary guardian.”

“What Pat means, Miss Black, is that she trusts your judgment in some matters far more than she trusts mine—or her mother’s.” As Mr. Taylor spoke there was still a baffled look on his round face. “I can understand it,” he went on. “You’ve had a wide experience of the world and of all sorts of people—especially young women. It isn’t always the parents who are best fitted to understand their children.”

“But what is there I can do?” Maria questioned, spreading her hands. “I can only sympathize—nothing more. Pat, you surely don’t expect me to try and guide your future life now that you’ve lost your intended husband?”

“It isn’t that which worries me, Miss Black; it’s the motive for Keith killing himself.”

“You just said it was jealousy.”

“Yes, I did, but…,” Pat reflected; then: “That’s what I think, and the more I think of it, the more I believe Greg may be right in saying it’s unconvincing. Perhaps there was another reason, but I’d never be able to find it. On the other hand, you might.”

“I?” Maria repeated. “How?”

“I don’t know. You have such funny ways of finding things out when you want to.” Pat sighed. “Oh, I’m all mixed up! What I’m trying to say is that Keith perhaps killed himself for a reason we none of us suspect, something perhaps that will never be revealed, not even at the inquest. For my part I’ll never rest until I know why he did it.”

“Evidently,” Maria said, “you are a trifle confused, Pat. You need time in which to think things out properly. However, if you feel I may be able to help you in any way, I’ll be only too happy. Sightseeing is hardly my exclusive idea of entertainment if there is a more human problem to tackle—”

“That’s what I wanted you to say!” Pat cried in sudden eagerness. “Stay here with us, at least till after the inquest.”

Maria shrugged. “If you wish.”

Taylor moved and managed a smile. “In future, Miss Black, I shall never believe the things I hear about headmistresses,” he said seriously. “When Pat said she wanted you to come and join her celebration, I thought she was crazy. Now I know otherwise.… You stay here and make yourself at home. Your bags are in the car?”

“Yes. In the back.”

“I’ll get them. And I think your car should be okay in the driveway. Unfortunately the garage is filled up with a broken-down Hillman and I can’t move it.”

* * * *

It was eleven o’clock when Maria retired to the large bedroom at the front of the house that had been placed at her disposal. She had had a meal with the family at eight-thirty—which had been consumed more as a token gesture than aught else—and had spent the rest of the evening making unsuccessful efforts to steer clear of the tragic topic with which they were all absorbed. The only diversion had come in the shape of a reporter who had rooted for facts, until he had been driven out by Maria’s cold eyes and her demand that the bereavement of the people concerned should be respected.

Now she half lay in bed, pillows at her back, a bed-jacket about her shoulders and a lacy boudoir cap perched on her wealth of hair. Released from the imprisoning moorings of the daytime, it fell in waves and curls to well below her shoulders. Even at this age she had a mellow, aloof beauty all her own. A trifle strong perhaps, but to many a man of mature years it would have appealed.

The book she was reading, Reik’s The Unknown Murderer, did not appeal to her as much as usual. Her invariable half-hour of crime study, which for nearly twenty years she had pursued upon retiring, was clouded tonight by other considerations. Better than anybody in the house she knew that suicide by hanging could just as easily have been murder, it depending upon the skill of the murderer whether or not the fact was apparent to the investigators.

“My singular gift of walking into tragedies does not seem to have deserted me,” she confessed to herself, presently. “Or is it that there is really nothing extraordinary about it? Tragedies are taking place every day. Sometimes there are deliberate crimes; sometimes there are perfect crimes; sometimes there—”

A gentle tapping on the door stopped her. Maria frowned.

“Yes?” she called. “Come in.”

It was the slender form of Pat who entered, a robe sashed in to her slender waist over her pyjamas. She closed the door softly, turned the key, and glided to the bedside. The table light caught her pale, straight features and the sheen in her dark hair.

“I’m glad you’re not asleep, Miss Black,” she murmured.

Maria laid her book aside. “I never succumb before midnight, my dear, and then I only permit myself seven hours. Bring up a chair.”

Pat did so and sat down, sighing a little to herself. Maria sat considering her.

“I thought I ought to tell you, Miss Black, that I had a yery good reason for asking you to stay. It wasn’t just for the purpose of—of moral support.”

“That much I had already assumed,” Maria commented. “You really asked me to stay because you are not satisfied with the circumstances of Keith’s suicide. Right?” Maria cleared her throat and became suddenly businesslike. “Well, Pat, come now. You didn’t creep in here just to sit and mope. You must have had a reason. What was it?”

“I’ve had an awful thought ever since Keith was found,” Pat said. “Do you think that he might have been murdered?”

“Do you?” Maria asked directly.

“I don’t know.” Pat rubbed a hand wearily across her forehead. “I’ve got a sort of feeling—woman’s intuition maybe.”

Maria laughed shortly. “There isn’t such a thing; take my word for it. A woman is a more sensitive animal than a man, yes, and for that reason only her imagination is usually keener. Intuition? No, my dear!” And she folded her heavy arms and waited.

“Well, then,” Pat said, “let’s put it another way. There was something about Keith’s death that wasn’t right. I said jealousy made him do it because I couldn’t think of anything else, but somehow I just don’t believe that myself.” Pat leaned forward in sudden urgency, her fingers picking at the coverlet. “Miss Black, you know a lot about crime and the reactions of criminals. Why don’t you make some suggestion?”

“You don’t expect me to say that I believe your fiancé was murdered, surely?” Maria asked, astonished. “I haven’t a shred of proof. I know hardly anything about his associations, his reactions, or if it comes to that, his movements before he committed suicide.… Certainly I dabble in crime and at times I—hmm—have been able to help the police here and there, but only because I am untrammelled by regulations and can move freely, adopting the methods of investigation laid down by experts in their textbooks. In this particular case I cannot—nor would I—make comment. The police have been called and they will sift the matter to the bottom. If there is any question of its being murder, you can rest assured they will find it.”

“But how can they? There’s nothing to go on—except the rope with which Keith hanged himself.” Pat bit her lip. “That won’t tell them a thing!”

Maria smiled. “On the contrary, my dear, it will tell them a great deal. It will depend on which way the rope fibres point.”

Pat frowned. “The rope fibres? What have they got to do with it?”

“That rope,” Maria said deliberately, beginning to enjoy herself, “will now be in the hands of micro-analysts in the forensic laboratory. It will be microscopically examined. The rope will show if the weight was thrown on it suddenly—as in a genuine suicide—or if Keith was murdered and then hanged. The difference is between what is technically called ‘slow strain’ and ‘two-way pull’.”

“Oh!” Pat grimaced. “That’s rather horrible!”

“Horrible? Not at all. Perfectly normal forensic technique. But tell me, Pat, surely you don’t think your fiancé was murdered? Who would want to do such a thing to him?”

“I’ve no idea.” Pat shook her head gloomily. “It’s simply that I can’t think he’d want to commit suicide, therefore the only answer is murder. I don’t know why, or who, or anything about it. In fact, nobody at the party could have done it because none of us left the room until it was found Keith had vanished.”

For a space Maria reflected, then she shook her head slowly.

“I think you’d better try and keep your imagination in check, Pat,” she advised. “You must be mistaken. I think the truth is that you can’t believe the facts.… In any case, if you have come here to ask me to do something, I just can’t— not until I have all the details. The best thing I can do is attend the inquest and then let you know what I think.”

“Yes,” Pat agreed listlessly, rising and returning the chair to its position beside the wall. “I suppose that would be best. I’m sorry I bothered you at this hour, Miss Black.”

Maria’s only response was an indulgent smile. She sat pondering for quite a time after the girl had left.