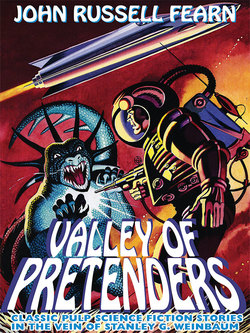

Читать книгу Valley of Pretenders - John Russell Fearn - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION, by Philip Harbottle

The two best-known early science fiction magazine pseudonyms of English writer John Russell Fearn were ‘Thornton Ayre’ and ‘Polton Cross’. The perceived wisdom amongst SF commentators is that both pseudonyms were conceived by Fearn more or less simultaneously in 1937 in order to increase his chances of selling to the American pulp magazines. And further, that initially stories under these names were written in an imitation of the style of the late Stanley G. Weinbaum. Then, when the ‘fad’ for Weinbaum imitations began to die out in the magazines—led by John W. Campbell at Astounding—Fearn changed his style and thereafter wrote under both pseudonyms in his own original style (or rather, two styles.)

Whilst such a summation is broadly correct, it is actually grossly simplified, and barely hints at the full, quite complicated background story. The full story of Fearn’s Weinbaum imitations is rather fascinating, and has never been fully documented. The present two-volume Borgo Press original set, World Without Chance and Valley of Pretenders, which collects these stories for the first time, is the result of many years of research. It uses primary sources that, collectively, are simply unavailable to other commentators. Most valuably, I been able to draw on information contained in Fearn’s personal prewar and early wartime letters to British SF magazine editor Walter Gillings, and to his friend and fellow author William F. Temple. Additionally, I have complete runs of the early magazines during the period Fearn contributed to them, and I myself have conducted further correspondence with Fearn’s agent at the time, the late Julius Schwartz, and with Geoffrey H. Medley. Medley, who lived near Fearn in Blackpool, was one of Fearn’s closest prewar friends. In his letters to magazine editors, Fearn had claimed that ‘Thornton Ayre’ was actually one Frank Jones, who was initially resident in the same house as Medley!

In October 1952, some five years after the last Thornton Ayre story had appeared, Fearn gave a speech as Guest of Honour at a Manchester SF Convention. He was then questioned about his pseudonyms and asked directly as to whether he was ‘Polton Cross’ and ‘Thornton Ayre’. He readily confirmed he was Cross, but had apparently replied that he was not Ayre, and that the name belonged to a friend of his, Frank Jones! His talk was reported in a couple of UK fanzines, the most detailed account appearing in Camber No. 1 (1953), written by attendee H. P. ‘Sandy’ Sanderson. Speaking about the Ayre byline, Sanderson wrote:

“Reverting back to pen names, he does insist that Thornton Ayre is not one of his. Apparently it belongs to a friend of his, Frank Jones. Mr. Jones does a lot of travelling, and he leaves his MSS with JRF. Publisher’s sending cheques to JRF’s house must have assumed he was Thornton Ayre.”

We can’t know if Sanderson’s account was entirely accurate, but the salient fact was certainly confirmed in a concurrent report in another fanzine by the Liverpool fan Group that stated: “Polton Cross is one of his pseudos, but Thornton Ayre, it seems, is not.”

But if Fearn’s remarks were correctly reported, it seems clear that he was speaking with his tongue very firmly in his cheek, and was just pulling the legs of his audience, for he most assuredly was Thornton Ayre! It would seem that Fearn could never quite get over the fact that his secret authorship could have been exposed when the Thornton Ayre byline had in fact been invented and used by someone else!

But who was this Frank Jones? Did he really exist? Hitherto, no SF historian or commentator has ever troubled to find out. The assumption has been that he did not exist.

In point of fact, Temple’s correspondence in the late 1930s contained many letters actually signed ‘Frank Jones’, and claiming to be that separate person, By then Jones was no longer living at the same house as Geoff Medley, and the letters to Temple gave his address as that of Fearn—Jones was now allegedly lodging at Fearn’s home!

Recalling these letters from Thornton Ayre (which he generously allowed me to copy), Temple told me: “…Jack kept trying to kid me he was really another person. I didn’t believe it…but I played along with him for the fun of it.”

In his first letter to Fearn’s alter ego Frank Jones (Thornton Ayre) in December of 1939, Temple touched briefly on the personal side:

“Re you being Jack—Jack has told me you are not, and I’m quite willing to believe him. In fact, I’m sure that Thornton Ayre and JRF are too different personalities. I do not pursue inquiries as to whether Jack is schizophrenic or not; his business is his business and not mine, or anyone’s. All I know is that he is a decent chap himself, generous and helpful to those who cannot be helpful to him; and an unfairly maligned author. I hope you won’t think it is flattery if I say that your letter shows traces of this same unasked-for generosity too. To continue this psycho-analysis, I’d say that this generosity is not a weak point because you both have hard business heads (which I definitely have not) and have it well under control.”

And to add to the mystery, Walter Gillings’ earlier 1936-1938 editorial correspondence details separate story submissions from a Frank Jones, sent from a different address than Fearn’s!

So how to reconcile the above with the fact that all of the published Thornton Ayre stories were all quite definitely written entirely by Fearn? My own careful analysis of the style of the Ayre stories—and much more significantly, the fact that years later Fearn would “mine” many of these stories and incorporate them, in adapted form, into his own novels, not to mention his reprinting several of them in the British Science Fiction Magazine in 1954-55, after he became its editor, have established Fearn’s sole authorship beyond all reasonable doubt. And the only story actually published under the name Frank Jones (“Arctic God”, Amazing Stories, May 1942) was also definitely 100% by Fearn. So…was there really anyone called Frank Jones? And what was his connection with ‘Thornton Ayre’? I have now uncovered the answer to that question.…

Around 1935, Fearn had become a member of the Blackpool Writers’ Circle, one of the many regional writers’ club support groups which flourished in England, and who were the target audience for Hutchinson’s national monthly magazine The Writer, which gave them publicity and regularly printed the addresses of their Secretaries. The first Secretary and founder of the Blackpool group was Miss Margaret Dulling, who was later to become a very successful romantic novelist, writing as Margaret St. John Bathe. Two young sisters, Doris and Muriel Howe, also became prolific romantic novelists. Yet another successful romantic novelist to emerge from the Circle was Iris Weigh. Iris became a particularly close friend of Fearn’s, and when he founded a rival Circle, the Fylde Writing Society, after the war, she moved to join him there.

Because of his rapid success in the American pulps, Fearn soon became a leading light in the Blackpool Circle, and he would have been friendly with one Frank Jones, who took over the Circle’s Secretarial duties in January 1937. The evidence for this can be found in the contemporaneous issues of the magazine The Writer, which announced that Frank Jones was now the Secretary, and gave his address as 51 Cheltenham Road, Blackpool—totally separate from Fearn’s address at 164 Abbey Road, Blackpool. So Frank Jones was a real person, and a writer.

On 7th September 1936 Gillings had informed Fearn that he had been secretly given the go-ahead by the World’s Work publishers to prepare a trial issue of a new British science fiction magazine, Tales of Wonder. Secretly, because a rival publisher, Newnes, was also preparing a new SF magazine, Fantasy. Jones had then been encouraged by Fearn to try his hand at writing science fiction short stories, with Fearn subbing and revising his mss.

Frank Jones’ first story was submitted to Gillings on 18th September 1936 on his behalf by Fearn. His covering letter to Gillings read:

“Herewith is Frank Jones’ ‘Mr. Podmore Does It,’ written under the name of ‘Briggs Mendel’. I’ve read it through and made one or two minor pen corrections. Personally I don’t think it half bad. If you can give him a break any way it will encourage him a lot. He has other Podmore stories, which he intends to work on. I feel, and maybe you will too after you’ve read it, that a series of this quaint little gentleman will interest British readers quite a lot. Enclosed also is one of mine which I came across. ‘Planet X,’ refused recently by Thrilling Wonder Stories as not quite convincing enough, but would, I feel make a good English one.”

Gillings was told to reply to Jones direct concerning his story. Gillings, however, had very rigid editorial criteria—he was reluctant to use anything that was too imaginative or took SF tropes for granted, in the style of the US pulps, He rejected and returned Jones’ first story.

On 27th January 1937, Fearn sent the following ‘Flash’ to Gillings:

“Thrilling Wonder Stories have accepted my ‘Lords of 9016.’ Frank Jones, whom you met in London, is writing science fiction under the name of ‘Thornton Ayre’ (and this name only must be used in publications, not his own.) Julie [Schwartz] thinks he has promise. He tells me that he’s just done ‘Little God’, after his first, ‘Composite Man’, failed. Oddly enough, Julie believes he might click. Will send you his address when he gets it fixed. Like me he is in removal at the moment.”

On 22nd February 1937, Fearn again told Gillings:

“Now here’s something else. I spent Saturday evening with Frank Jones—or, as he calls himself for fiction—Thornton Ayre. So his name won’t leak out and perhaps queer his pension for an accident of long ago, I suspect. Anyway, I do believe I had that guy all wrong! He can write SF! His latest story, ‘Dark World’, is in my opinion a corker with real thought-variant slants. Can it be that a rival grows on my own doorstep? Anyway, I’ve suggested that he write to you so perhaps he did so over the weekend. In any case—confidentially—though he seems a bit odd on the surface, he certainly knows how to slap words together. I’m very surprised to find he really knows his stuff. Unless I’m mistaken he will click before long.”

On 4th March 1937 Gillings told Fearn that Frank Jones had indeed contacted him direct, and he was intending to give him a write-up in the next edition of his printed fanzine Scientifiction. Sure enough, there was an announcement in the magazine’s second, April 1937 issue:

“Another newcomer to fantasy field is Thornton Ayre, Blackpool protégé of John Russell Fearn, who predicts he will burst into print shortly with thought variant, ‘Dark World’, following inevitable rejections of first efforts.”

On 24th April 1937, Fearn told Gillings in another letter:

“Here’s another secret—for you ALONE and not for any publication. Schwartz has suggested, in view of my turning out work so fast as Fearn, that I become somebody else with a totally different style, different typewriter, different paper and what not. So I have become Polton Cross (a village two miles out of Blackpool) and have turned out two yarns on the Weinbaum style, namely ‘World Without Chance’ (10,000 words) and ‘Outpost’ (6,000). If these yarns do click, I defy you to tell it’s me, so totally new is the arrangement of the ideas. The idea being, of course, that Fearn and Cross can click simultaneously and double my chances all round.

“I’ve only told Frank Jones about World’s Work—and your secret is safe with him. He wants to know if you’d like to see some of his work? Carbons, I suppose. Maybe he’ll write you himself, but if not perhaps you’ll tell me and I’ll relay it. He’s rather a dilatory letter writer. He’s down in the mouth too because he hasn’t clicked over the ocean so far.”

In the ensuing months, from time to time, Jones tried Gillings again, but without success. In order to try and help his friend, Fearn’s revisions to his mss. became more and more extensive, so much so that Gillings actually doubted whether Frank Jones actually existed; he suspected that the prolific Fearn (who was himself submitting stories unsuccessfully to Gillings under his own name) was using a pseudonym to increase his chances of success.

In this Gillings was initially quite mistaken. Frank Jones was a member of the Blackpool Writers Circle. But the overly-suspicious Gillings remained intractable. He remained equally so when Fearn began to submit mss. by his other friends in the Blackpool Circle, Edgar Spencer and Geoffrey Medley.

On 26th May 1937 Fearn wrote Gillings again:

“You’ll find an MS herewith from Geoff Medley. He lives at the same house as Frank Jones, and, to my mind, has turned out a fairly decent English or Amazing type sf yarn. I suggested he might try you before Amazing and see if you could find room anywhere in a future edition of Tales of Wonder for him. I’ve enclosed a stamped envelope for him. Please write to him direct. Don’t be too hard on the guy. He spent all his Whit Weekend typing on this machine (which he borrowed) in order to complete the yarn. If you think anything of it, OK. No business of mine.”

But Gillings would reject this story, plus Medley’s follow-up effort, “Carcinoma Menace”.

On June 10th 1937 Fearn reported to Gillings:

“Julie thinks that ‘World Without Chance,’ Cross’ first effort, is a first class effort and remarkably like Weinbaum. Same applies to ‘Chameleon Planet,’ which I’ve just completed. If Cross should prove more of a hit than Fearn I’ll be tickled to death!”

Fearn wrote to Gillings again on 19th June 1937:

“I saw Frank Jones the other day and so far his yarns haven’t clicked in the US, because they’re too simple. I’ve read them through and I think they’re pretty good for England. I’m attaching their synopses also. If you think them worthy I’ll get him to send them on.”

I managed to trace and contact Geoffrey Medley a number of years ago, and he told me how he had come to know Fearn:

“Fresh from school at the age of fourteen, I reported to 15, Birley Street, Blackpool, to take up the duties of junior office boy to the pompous Mr. John W. Roberts, Solicitor, Town Councillor and drunkard.…”

Geoff went on to identify the other staff members, including the senior office boy, the common law clerk, the secretary and cashier. He continued:

“…During my five years at Birley Street (we moved from No.15 to No.16, across the road) other junior office boys came and went.… It was some time before I came to know the part-time typist. Full-time there was Marjorie Nixon, plus another girl whose name I forget. But this man was of another world. He showed no knowledge of law, no interest in the clients at the practice, and he seldom spoke to anybody. At irregular intervals he just was there, hawk-nosed, smouldering-eyed, apparently unaware of his surroundings. Usually a cigarette dangled from one corner of his mouth, and one eye was half-closed against its rising smoke, as two fingers of each hand pounded the keys of the big, brief-carriage typewriter, churning out abstracts of Title—long, rambling documents—faster than the girls could type with five fingers, and faster than I have ever heard a man type.

“This was John Francis Russell Fearn.

“Gradually I came to know that he did our typing jobs just to eke out, and that his main occupation was writing magazine stories. This was exciting news to a boy who had always been top of his classes in English and who vaguely felt that his own best hope of success was to be a writer. And when Jack learned this he was more than helpful. I came to know Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories, and his contributions to them.…

“I went to his house and used his typewriter to rattle out my own attempts at science fiction stories, which he read through and said were in his opinion worthy of publication. The magazine editors never agreed. In retrospect I think the yarns were too juvenile. The only one I remember now [‘Carcinoma Menace’—editor] was about a cancer sufferer in whom the malignant cells, treated with radiation in an effort to kill them, reacted rather unexpectedly. The radiation triggered off mutations in the cells, and the chap finished up with an intelligent being—malignant, of course—inside him, and taking over. The science was suitably blinding, but the fiction, I fear, was rather lame.” [In point of fact, this plot seems to be an uncanny anticipation of one used by John Kippax (John Hynam) in his powerful short story “It” a full twenty years later in Nebula, November 1958 issue!—editor]

“Sometimes we took a break from writing, largely at Jack’s mother’s instigation, and we all three played Bezique, watched by ‘Benjie,’ their wire-haired terrier.”

By then Medley had joined the Blackpool Writers Circle, where he would also do a stint as Secretary later in 1938 (taking over from Fearn, who had succeeded the now departed Jones). Geoff recalled these days thusly:

“Coming back to the period when I was typing my MSS at the Fearn house, I recall that Jack was working on a ‘straight’ novel in the intervals between writing his science fiction potboilers. It was called Little Winter, and dealt with Blackpool seen from the resident’s viewpoint. I don’t remember his completing it.” {Fearn did in fact complete this during the war, and entrusted it to a literary agency. Unfortunately it never sold, and the MSS was inadvertently destroyed following the death of his widow in 1982—editor}.

“Jack and I were members of the Blackpool Writers’ Circle, which met on one evening each week in Jenkinson’s café, in Talbot Square. Jack was then the only full-time writer in the membership.”

Other members whom Geoff recalled included Edgar Spencer and Arthur Waterhouse Painter (“whose legs were paralyzed”. [Painter became a particular friend of Fearn and his mother, and was a very successful writer of juvenile fiction after the war; he also appeared in the Vargo Statten/British SF Magazine—editor.] Geoff continued his reminiscences:

“The Misses Howe were our most regular attendees. One sister, innocent of make-up, wrote for publications like The Methodist Recorder. The other, more smartly dressed and colourfully powdered, wrote for more romantic women’s magazines.

“We all discussed and criticized the MS. of the evening, giving quite well-reasoned analyses, and being ever mindful of the criteria which the books on writing laid down. All except Jack. He listened gravely, but his own contributions to the criticism were not particularly well argued or explained. All Jack could do, really, was write—and make money by it. The rest of us seldom sold anything.

“I lost touch with Jack during the War, and I outgrew my boyhood interest in science fiction. The brown Bombardier who produced and acted in plays in the Orkney Islands was a different person from the wide-eyed youth who had concocted ‘Carcinoma Menace’. Or nearly. Just once my old science fiction familiarity surfaced. It was on Salisbury Plain. One of our sergeants came back from the mess bubbling over with good news. ‘You know them bombs, Geoff, that they used to bust them dams in Germany—they were over a ton apiece. Well, it’s on the wireless over in the mess, we’ve got a bomb over a hundred times more powerful than them, and do yon know how big it is?’

“I froze. His lead-up could only be to an impressively smaller bomb.

“‘Christ!’ I said. ‘Don’t tell me they’ve already got some form of atomic power.…’

“‘That’s what they said—atomic or something.…’

“‘Now,’ I said, ‘we’re really in trouble.’

“‘You don’t understand, Geoff. We’ve got it—not them.’

“It took a science fiction man, then, to realize what trouble we were in.”

In a letter dated 5th July 1937, the suspicious Gillings told Fearn:

“I’m afraid, as far as my anticipations go, ‘Thornton Ayre’ doesn’t get much of a look in; nor, so far, does your friend Geoff Medley, whose ‘Death From the Star’ is much too advanced. Incidentally, these two write surprisingly complex stuff for amateurs at SF don’t they? Particularly Frank Jones, whose style and ideas are remarkably reminiscent of your own. So much so that in ‘Dark World’ he gives almost word for word the same account of the destruction of Atlantis as you do in your ‘Born of Atlantis’ (which would be okay for England if it was more leisurely-written and more convincing in spots, by the way), and even chooses the same name—Izma—for the arch-villain scientist, also making the same acknowledgement to Manly P. Hall! Can you explain this, to satisfy my curiosity?

“I still don’t realize who Frank Jones is. You say I met him in London. I recall meeting two of your friends; the tall one, who said little, and the other one who spoke so quietly, and who seemed to have invented such a lot of useful things. Is he the latter? I believe it was he who wrote the Podmore story you sent me before Sprigg closed down; if so, he’s improved mightily since then.… How was it his yarns didn’t click in the U.S.? They seem just cut out for Thrilling Wonder to me. Medley, however, wants a little more practice, though he certainly has ideas.”

Fearn replied on 7th July 1937:

“Haven’t seen Geoff or Frank, but I guess they’ll both be a trifle cut up. No matter—the editor’s decision is final. Jones is the tall one who spoke little; the other is Ed. Spencer. With regard to Jones’ stories, probably the similarity of style is accounted for by the fact that I did piles of correction to his MSS to try and help him, and my own flavouring has crept in. I noticed it myself. The destruction of Atlantis accounts being similar is easily explained since they’re both lifted piecemeal from the quotations of Manly P. Hall, hence the acknowledgement in both cases. Afraid I can’t figure out how we both got Izma. Unless with his reading my ‘Born of Atlantis’ he unconsciously clicked on the same name. I didn’t remember the name again when I read his, which shows my rotten memory for the things I write.

“Frank Jones’ yarns didn’t click for Thrilling Wonder because they were too tame and too unconvincing, I understand. Ah me!”

Fearn, meantime, had learned from Schwartz that “World Without Chance” by Polton Cross had been accepted by Thrilling Wonder Stories in July 1937, but that publication was likely to be delayed for some little time, because the magazine was overstocked. At this point, it would appear that Frank Jones more or less gave up any hope of making it as a SF writer. Fearn may have told him that since he was now writing stories as Fearn and Cross, he was unable to extensively rewrite his mss. as he had been doing. It is not known what became of Jones, but it is possible that the clinching reason why he gave up SF writing was that he may have left Blackpool altogether. Fearn had stated that his regular profession was that of a commercial traveller.

However, Frank Jones would have been grateful to Fearn for the help he had given him, and so, whilst dropping out of writing himself, he must have agreed that Fearn could appropriate his—as yet unpublished—pseudonym ‘Thornton Ayre’, And Geoff Medley agreed to let Fearn continue to use his (Medley’s) home address on his ‘Thornton Ayre’ mss.

For the astute Fearn had scented a golden opportunity, and hatched a cunning scheme. Whilst his agent Schwartz knew that Fearn was Polton Cross, and would keep this a secret for commercial purposes, Schwartz also believed that ‘Thornton Ayre’ was another person entirely—Frank Jones. As indeed he then actually was! But what if Fearn was to now begin secretly writing stories himself as Thornton Ayre, also in the Weinbaum style? With Schwartz believing he was still Frank Jones (the Weinbaum imitation technique would effectively disguise the fact that Fearn and not Jones was now writing the stories), Fearn reasoned that his chances of regular sales under all three names, Fearn, Cross, and Ayre, would be immeasurably increased.

How right Fearn was would soon be proved when the January 1938 Astounding Stories would carry stories under all three names—“Red Heritage” by Fearn, “Whispering Satellite” by Ayre, and “The Mental Ultimate” by Cross! (He would repeat the same trick in the May 1942 Amazing Stories, even adding a fourth story—as by Frank Jones!)

When I wrote to Julius Schwartz in 1983 (after I had discovered in The Writer that Frank Jones had been a real person), and asked him if he had known Fearn was Thornton Ayre when he began selling his stories, he confessed:

“I didn’t deduce that Thornton Ayre was Polton Cross till much later! Same goes for the SF Editors!”

John W. Campbell was certainly one of the editors to be fooled. The January 1938 issue of Gillings’ fanzine Scientifiction ran a real scoop article, “Campbell’s Plans for Astounding”, quoting from a postal interview with Campbell himself.:

“Included in the January (1938) issue will be stories by Warner Van Lorne, Clifton B. Kruse, John Russell Fearn, Thornton Ayre (the English Author, whom Campbell describes as ‘one of the best of the newer writers’), and Don A. Stuart, otherwise Campbell himself.”

On November 25th 1937 Fearn had told Gillings:

“Frank seems to be doing all right for himself. I understand that Julie highly praised his recently sold ‘Whispering Satellite’ as one of the best things he’d read. I did think it was tops myself, though confidentially how he ever manages to have such a swell slant on the Weinbaum angle will be an eternal mystery to me. His latest efforts, ‘The Minitors’ and ‘Sanctuary’, are both real pips. Certainly he no longer needs me to help him!”

Thereafter, all of Fearn’s Thornton Ayre stories would be first directed to America, and all of them would eventually sell there.

So there we have it. Frank Jones had indeed been a real person, and, coached by Fearn, he had tried writing SF in 1936 (as Briggs Mendel) and continued into 1937 (as Thornton Ayre). Then he had given up and handed his Thornton Ayre pseudonym to Fearn, who had already created his own pseudonym of Polton Cross, initially writing in the style of Weinbaum. And when Fearn began writing Ayre stories, even more blatantly in the style of Weinbaum, he was initially very successful, selling his first two stories to Astounding Stories. For his ‘Cross’ efforts, Fearn abandoned the Weinbaum slant, and instead developed a third quite distinct style of “scientific nemesis” stories, beginning with “The Mental Ultimate” (Astounding Stories, January 1938).

What happened next is best illustrated in an article Fearn wrote (as Thornton Ayre) that was published in the March 1939 first issue of Ted Carnell’s fanzine New Worlds, entitled “Concerning Webwork”:

“Some little time ago a much esteemed mutual friend Julius Schwartz paid me the compliment of calling me a webwork writer. Since then the words have stuck in my mind—and since English readers will be as much in the dark as I was I might as well explain that ‘webwork’ means a complicated mystery wherein all the strands are drawn together in the last chapter to form the complete whole. By accident I stumbled upon this mystic formula in ‘Locked City’ and repeated it in ‘The Secret of the Ring’ (originally called ‘The Circle of Life.’)

“Now all of this brings me to something. If webwork mystery is a new slant to science fiction—and presumably it is—what a colossal field it opens up for other writers as well. I don’t mean in webwork (I stick to that now as my personal angle) but in other slants. Consider a moment—what has SF been like up to now? I am virtually new to the game but I’ve read tons of it since being a boy.

“Here’s my reaction. It’s all been adventure. The pages of past SF reek with curly headed heroes and smooth hipped heroines. Villains have been monstrosities of other worlds. Rarely if ever was the formula altered, save for a few gems from Campbell, Smith, Keller or Taine. Yet even they—though their characters were life-like—pandered to the eternal hackwork adventure formula.

“Yes, and even Weinbaum. What are all his stories but adventure? True, they are magnificent adventure with living people—but they remain the same.

“For myself, I copied his style in my yarns ‘Penal World’ and ‘Whispering Satellite’ because, in the words of the old song, ‘It seemed the right and proper thing to do.’ Then it occurred to me, after a series of rejections, that something had gone wrong. I needed a new technique—I tried a complicated mystery ingredient added to adventure. It worked!”

These sidelights on Fearn’s writing as Ayre were further clarified when Fearn wrote an “About the Author” article to accompany his Thornton Ayre story “Face in the Sky” in the September 1939 Amazing Stories:

“…It all started about two years ago when I was getting pretty fed up with poor returns from occasional articles and short straight yarns in England. You see, the trouble over here is they don’t like anything sensational, or off the beaten track. At least, they didn’t then! But times are changed.

“As I was saying, I was getting fed up when my closest friend, the redoubtable dynamo known as Fearn, slanted my ideas towards science fiction. I’d read several odd tons of the stuff and I must confess it had appealed to me quite a lot. I thought there was nothing to lose by having a shot at it—but oh! Those first efforts were pretty awful, My brains, what there are of them, revolved around queer asteroids, men down in the sea, talking protoplasm, and other things usually associated with over-indulgence in opium or heavy cheese late at night.

“About that time Stanley G. Weinbaum was at his peak. Everybody was nuts about his particular slant and so, being a trier, I imitated his style and produced Jo, the ammonia man of the planet Jupiter. This was in the yarn ‘Penal World’ published in Astounding, in 1937. Shortly afterwards I followed it up with a similar type of yarn called ‘Whispering Satellite,’ also in Astounding. On that point my activities with Astounding terminated because everybody was going like Weinbaum and the Editor was plenty sick. Campbell wrote me an explanatory letter and suggested changes of style.

“I chewed things over. The science fiction business was getting a hold on me, and imitation would not do any longer. Why not try the other extreme and find out what had not been done? I felt I had got something there. Well, what hadn’t been done? Mystery!

“Mystery! Of course! So far as I could figure out all the yarns were more or less straight experiments, adventures, theories—or, very rarely—a detective sort of problem. But what about a real juicy mystery woven round with science? Something to explain Mars, for instance, as it had never been explained before?

“So I launched on a style which, I have since found, was unique. I unwittingly brought webwork plots into science fiction with my initial yarn in a new style—’Locked City.’ The praise for that one made me all of a benevolent glow and produced ‘Secret of the Ring’ (which I shall always privately regard as the best yarn I’ve written so far).”

Fearn’s initial stratagem to write stories as Polton Cross in imitation of Weinbaum (who had died in December 1935) would almost certainly have been suggested to him by his U.S. agent, Julius Schwartz. So when shortly thereafter ‘Thornton Ayre’ followed suit, Schwartz would have been quite happy about it.

Schwartz, in fact, had been Weinbaum’s agent, and in 1937 he was also representing many of the most prolific and successful American authors. It was surely no coincidence that many of those in his stable all began to write Weinbaum imitations at about the same time.

In his introduction, “The Wonder of Weinbaum” in the landmark Weinbaum collection, A Martian Odyssey (Lancer, 1962) the leading SF historian Sam Moskowitz outlined just how celebrated and influential Weinbaum’s short career (1934-35, with posthumous stories in the next few years) had been:

“Many devotees of science fiction sincerely believe that the true beginning of modern science fiction with it emphasis on polished writing, otherworldly psychology, philosophy and stronger characterization began with Stanley G. Weinbaum. Certainly few authors in this branch of literature have exercised a more obvious and persuasive influence on the attitudes of his contemporaries and through them on the states of the readers.…

“…what cannot be argued away are the strong influences of Weinbaum to be found in the work of authors as outstanding in science fiction as Henry Kuttner, Eric Frank Russell, Philip Jose Farmer and Clifford D. Simak specifically.”

The full roll call of other authors following in his footsteps is even longer, including, amongst others, Arthur K. Barnes, Eando Binder, Moskowitz himself, and not least John Russell Fearn.

Their borrowings involved not just the stories themselves, but Weinbaum’s astronomical backcloth to his stories. This useful framework was astutely identified by Isaac Asimov in his brilliant introduction to The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum (Del Rey, 1974):

“Weinbaum had a consistent picture of the solar system (his stories never went beyond Pluto) that was astronomically correct in terms of the knowledge of the mid-1930s. He could not be wiser than his time, however, so he gave Venus a day-side and a night-side, and Mars an only moderately thin atmosphere and canals. He also took the chance (though the theory was already pretty well knocked out at the time) of making the outer planets hot rather than cold so that the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn could be habitable.

“On each of the worlds he deals with, then, he allows for the astronomic difference and creates a world of life adapted to the circumstances of that world.”

These two new Fearn collections present all of the Weinbaum pastiches that Fearn published—a dozen in total. And, as a bonus, the second volume also contains a thirteenth story, “Locked City” by Thornton Ayre, his first story marking the radical new direction Fearn was to take when he abandoned the Weinbaum slant. Each story is annotated with further sidelights, setting the stories in the context of the science fiction magazine scene in the late 1930s and early 1940s, one of its most interesting and dynamic periods.

I hope you will enjoy reading these stories as much as I did compiling them…and that they may intrigue you enough to want to seek out Weinbaum’s own stories if you have not already encountered them.

—Philip Harbottle,

Wallsend, England, July 2012