Читать книгу Undead - John Russo - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

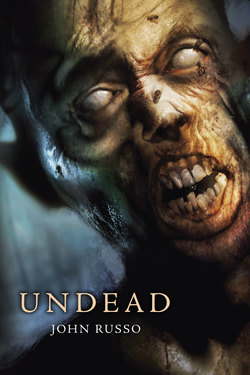

INTRODUCTION: THE BIRTH OF THE DEAD

ОглавлениеIn developing the concepts and writing the screenplays and novels for Night of the Living Dead and Return of the Living Dead, our overriding concern and aim was to give true horror fans the kind of payoff they always hoped for, but seldom got, when they shelled out their hard-earned money at the ticket booth or the bookstore. This was the guiding principle that we were determined not to violate. When I say “we” I am referring to Russ Streiner, George Romero, Rudy Ricci, and others in our group who contributed to the development of the scripts and the movies.

As a teenager, I went to see just about every movie that came to my hometown of Clairton, Pennsylvania. It was a booming iron-and-coke town in those days. There were three movie theaters, and the movies changed twice a week. Often there were double features—and the price of admission was only fifty cents! I loved the Dracula, Frankenstein, and Wolf Man movies—enduring classics, sophisticated and literate explorations of supernatural horror and dread.

But I also went to see dozens of “B” horror films, always hoping, against the odds, that one of them would turn out to be surprisingly good. This almost never happened. The plots were trite, formulaic, uninspiring. Decidedly unscary.

In the fifties, because of the vaporization of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, everyone was scared of nuclear bombs and nuclear energy—especially nuclear energy gone awry. This pervasive psychology of fear was ripe for exploitation, and it gave rise to the “mutant monster” genre of horror films. We were treated to The Attack of the Giant Grasshopper, The Attack of the Giant Ant…the Giant Squid…the Giant Caterpillar… and so on.

Did I say that the “plots” were trite? I should’ve said “plot” (singular) because the same plot was used over and over with each of the different mutated creatures. The giant whatever would be hinted at, but not shown in its entirety, somewhere within the first twenty or so very dull minutes. The audience at first would be teased with just a fleeting glimpse of some aspect of the monster. Then a bigger piece of it would appear to the town drunk, who was never believed by the authorities. He would usually be killed or devoured—but in such a way that nobody important ever got wise. Eventually the male and female “B” actors in the lead roles would start to catch on, but at first nobody would believe them, either. Then, during the last twenty minutes or so of the movie, our hero, who was conveniently a scientist, would figure out that the giant whatever’s saliva was identical to the saliva of a commonplace caterpillar or ant or octopus or grasshopper or whatever other kind of giant mutant that had to be dealt with—and this would culminate in a “grand finale” with National Guard troops arriving in the nick of time to destroy the horrible creature with flamethrowers and grenades.

Well, we didn’t want our first movie to be like that. As I said, we really wanted moviegoers to get their money’s worth.

In order to do this, we had to be true to both our concept and to reality. Granted, we were working with the outlandish premise that dead people could come back to life and attack the living. But, that being the case, we realized that our characters should think and act the way real folks, ordinary folks, would think and act if they actually found themselves in that kind of situation.

As the whole world knows by now, we didn’t have much money to make our first movie, and we were groping for ideas that we might be able to pull off, on an excrutiatingly limited budget. We made several false starts—one of these was actually a horror comedy that involved teenagers from outer space hooking up with Earth kids to play pranks and befuddle a small town full of unsuspecting adults. But we soon found out that we couldn’t afford sci-fi-type special effects and we had better settle upon something that was less FX-dependent.

George Romero and I were the two writers at The Latent Image, our movie production company at that time, and we would each go to work at separate typewriters whenever we could make time; in other words, whenever we weren’t making TV spots about ketchup, pickles, or beer. I said to George that whatever kind of script we came up with ought to start in a cemetery, because people were scared of cemeteries and found them spooky. I started writing a screenplay about aliens who were prowling Earth in search of human flesh. Meantime, over a Christmas break in 1967, George came up with forty pages of a story that did actually start in a cemetery and in essence was the first half of what eventually became Night of the Living Dead, although we didn’t give it that title till after we were done shooting.

I said to George that I really liked his story. It had the right pace and feel to it, and I was hooked by the action and suspense and the twists and turns. But I was also puzzled because “You have these people being attacked, but you never say who the attackers are, so who are they?” George said he didn’t know. I said, “Seems to me they could be dead people.”

He said, “That’s good.” And then I said, “But you never say what they’re after. They attack, but they don’t bite, so why are they attacking?”

He said he didn’t know, and I suggested, “Why don’t we use my flesh-eating idea?”

So that’s how the attackers in our movie became flesh-eating zombies. In our persistent striving for a good, fresh premise, we succeeded in combining some of the best elements of the vampire, werewolf, and zombie myths into one hellacious ball of wax.

Zombies weren’t heavyweight fright material until we made them into flesh-eaters. In all the zombie flicks I had seen up till then—most notably Val Lewton movies like I Walked with a Zombie—the “walking dead” would stumble around and occasionally choke somebody or throw somebody against a wall, or maybe, in the extreme, carry off a heroine to some sort of lurid fate—but they were never as awe-inspiring as vampires or werewolves. They were meant to be scary, but they were always a little disappointing.

Night of the Living Dead struck an atavistic chord in people. It was the fear of death magnified exponentially. Not only were you afraid to die, you were afraid to become “undead.” Afraid to be attacked by a dead loved one. And afraid of what you might do to your loved one if you, by being bitten, became one of the flesh-hungry undead that you feared.

Soon after our discussions, George Romero got tied up by an important commercial client and I took over screenwriting chores. That was the way we worked in those days. We spelled each other when necessary. And we all felt it was necessary to keep the ball rolling in these early stages so that our dream of making our first feature movie would not die.

In refining our concept, ideas were bandied about by me, George Romero, Russ Streiner, and others in our immediate group. Then I rewrote George’s first forty pages, putting them into screenplay format, and went on to complete the second half of the script. I wanted our story to be honest, relentless, and uncompromising. I wanted to live up to the standard set by two of my favorite genre movies—the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Forbidden Planet (with its “monsters from the id”)—and I hoped we could cause audiences to walk out of the theater with the same stunned looks on their faces that had been produced by those two classics. That is why I suggested that our indomitable hero, Ben (played by Duane Jones), should be killed by the posse that should have saved him. I said, “Pennsylvania is a big deer-hunting state, and every year three or four hundred thousand deer are shot—and ten or twelve hunters. With all these posse guys running around in the woods, gunning down ghouls, somebody is gonna be shot by accident, and wouldn’t it be ironic if it’s our hero?”

This idea got incorporated into the original screenplay as did other ideas, which were implemented during filming. For instance, the “Barbra” character, played by Judith O’Dea, survives in the screenplay as written—but we decided it would be better if her brother “Johnny” came back and dragged her out of the house to be devoured.

It wasn’t until 1973, after the movie had enjoyed six-plus years of phenomenal success, that I wrote the novel that was initially published by Warner Books. In the intervening years, Russ Streiner, Rudy Ricci, and I developed a screenplay for a sequel, Return of the Living Dead, which I later novelized. You are right now holding both original novels in your hands, appearing together for the first time, in this beautiful trade paperback.

I also wrote the novelization of Dan O’Bannon’s movie version of Return of the Living Dead, a hit in its own right. But the totally different novel you will read now is our very first conception—of stark horror. Not a horror comedy, but stark horror in the vein of Night of the Living Dead.

If the dead really did arise, and if they became flesh-eaters, they might be temporarily vanquished—but like a disease that is hard to stamp out, the possibility of a renewed “plague” would always be with us. Religious cults would spring up in the wake of the undead. Maybe they would believe that the dead still needed to be burned or “spiked.” And then what would happen? Would the cult’s grisly expectations be realized? Would the flesh-eaters come back? This was the question that we sought to answer in a powerfully dramatic way in our follow-up story. Which is decidedly unfunny. In other words, unlike the movie, it is not a horror comedy.

If you like good, strong horror—horror that you can believe in—I welcome you to the deliciously terrifying, no-holds-barred, gloves-off world of the original Night of the Living Dead and Return of the Living Dead.

John Russo

Pittsburgh, PA

February 2010