Читать книгу The Gods, the State, and the Individual - John Scheid - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTranslator’s Foreword

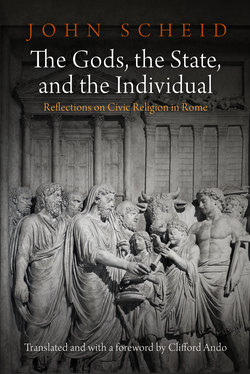

John Scheid’s The Gods, the State, and the Individual: Reflections on Civic Religion in Rome is an impassioned intervention in a contemporary debate in the study of ancient religion. It speaks for a method or, perhaps, a perspective, as well as a distinctive national tradition. In the book, Scheid himself contextualizes his work within a century’s history of scholarship on religion in the ancient world. This foreword offers an additional perspective on the contemporary context in which Scheid intervenes and explains choices made in the process of translation.

Roman religion has long presented a number of challenges to historians of religion in the Christian and post-Christian West. Among others, one might single out the nonexistence in classical Latin of any term that corresponds to English “religion,” and the similar absence of any vocabulary to discuss religious affiliation or acts of conversion that distinguish those phenomena from, say, acts of political belonging or changes in doctrinal persuasion in the study of philosophy. To these one might add Roman religion’s lack of a sacred text that (nominally) offered a totalizing portrait of the religion’s propositional content or foundational myth, as well as the Roman practice of describing relations with the divine using technical terms for social relations widely employed to discuss relations with other humans: pietas, whence English “piety,” describes dutiful respect toward ties of kinship above all, but also other social bonds; colere, whence Latin cultus and English “cult,” describes sustained acts of attention, respect, and cultivation toward things we cherish: social superiors, close relations, and the land whence one springs.

Building on a long tradition of scholarship, whose contours I trace below and in which he himself has played a leading role, Scheid confronts these challenges head-on. Proceeding with a profound respect for historical and philological detail, Scheid explores the functioning of a religious system tightly imbricated with other structures of social and political belonging. How shall we describe the situation of individuals vis-à-vis Roman religion, when the Romans themselves did not regard the individual as a primary unit of social analysis, freely making religious commitments that might emancipate or sunder oneself from other forms of social commitment? In addition, Scheid outlines and emphasizes the consequences of our accepting as historically primary features of Roman religion prominent in the sources (its emphasis on ritual action; its profound concern for the here-and-now), instead of seeking at Rome those features of Christian religious life that we would like to find, whose very lack then becomes at once an explanandum and the principal evidence for Roman religion’s deficiency as religion.

Scheid describes the emergence of what he alternatively terms a sociological or secular perspective on Greek and Roman religions as a hard-won struggle on the part of researchers to set aside a priori commitments, derived above all from Protestant Christianity, about what religion is and how individuals and communities relate to religions. In his view, nineteenth-and early twentieth-century historians of religion derived from Protestant theology and Romantic philosophy an understanding of religion as, in essence, an interiorized sense of individual dependence and awe before some unseen and transcendent divine. In that historiographic tradition, such feelings on the part of individuals have historically found collective expression in institutions and shared practices. For a multitude of reasons, individuals and cultures have often lost their way and become estranged from their own feelings and thus from the divine; religious institutions and practices are then hijacked by elites, who put themselves forward as experts—as priests—and exploit popular devotion to ritual and their own control over particular spaces, materials, and institutions of knowledge production to interpose themselves between individuals and the divine. Scheid’s work in this regard is part of a widespread and international tradition of self-critical reflection in the study of religion, and he is surely correct in the fundamentals of his diagnosis. An exemplary essay in the American branch of this tradition is Jonathan Z. Smith’s “On the Origin of Origins,” the first chapter in Drudgery Divine.1 Focusing ultimately on Protestant historians of religion of the nineteenth century and their influence in the United States, Smith shows, among other things, how Protestant efforts at self-differentiation vis-à-vis Catholic ritualism led to the misrecognition and denigration of any religious tradition in which collective ritual action was a preeminent form of religious expression. Many similar and also excellent works of historiography, from a wide variety of perspectives, might be cited.2

Although the way was paved by a number of earlier, excellent books—including, as Scheid and many others in the field emphasize, the extraordinary work of Georg Wissowa, Religion und Kultus der Römer3—the emergence of a new consensus was the result of convergent work in France and England in the 1970s and Germany perhaps a decade later.4 This new consensus had three features of importance here. First, contributors to it explicitly reflected on the need to identify and bracket assumptions about religion derived from the Abrahamic religions:5 those regarding the centrality of “faith” as an epistemic category (that religions are founded on belief) and a bundle of propositions (that religions have doctrines); the assumptions that religions are revealed to humans by gods who communicate with them in human language, and some, at least, of the content of those communications remains available in books, with all that entails about etiology, historical self-awareness, capacities for fundamentalism, and the need for interpretation; the assumption that adherents to particular religions properly display their zeal by persuading others to share that zeal;6 and so forth.

That said, Romans wrote books on religious themes and reflected both discursively and in figurative art on their own religious practices, and they performed rituals, even if they almost never attributed the content of those rituals to some originary moment of divine revelation. The second feature of the new consensus relevant to this sketch is thus substantive in orientation. Across a variety of domains, scholars have sought to craft frameworks within which to understand the role of religious literatures and other forms of aestheticized cultural production at Rome, including avowedly literary forms like myth as well as philosophical theology and figurative art: were they merely personal reflections on the meaning of ritual performance, which was somehow primary? Or can they serve as indices to interpretive or ideological agendas at their moment of production? How, in sum, should they contribute to the writing of histories of Roman religion?7

As a related matter, the nature of Roman ritualism has also been subjected to searching inquiry. If religion consists in nothing more than a set of gestures, is it devoid of theological or even ideological content? What does it mean to say that the Romans esteemed correct performance—that their religion was an orthopraxy, as doctrinal religions might esteem orthodoxy—when the evidence clearly suggests that performances might vary, one from another? How should we, and how did the Romans, understand religious change? Greeks and Christians rehearsed etiological myths; the Romans spoke in vaguer terms about the customs of their ancestors (whom they tellingly termed maiores—literally, their “betters”). How did these distinctive ideological positions find expression in patterns of fundamentalism and historicism in religious thought and practice?8 On another plane, how should one conceive the relationship of religious sentiment and affiliation on the part of individuals in such ritual systems? What did it mean to “participate” or “belong” to a civic religion?9

The final feature of this work on religion concerns the broader theorizing that it provoked. Scheid and many others use the terms “polis-religion,” “the civic model,” or, to refer specifically to the work of Richard Gordon, “the civic compromise” to describe the relevant theories. In abstract terms, these were attempts to describe Greek and Roman religions as symbolic systems within particular social, material, political, and economic contexts. At the level of method, this ambition encouraged a scrupulous historicism in regard to the actual practices of ancient worship and its imminent theorizations by participants, even as it worked to disallow any un-self-conscious or unreflective imposition of anachronistic or etic categories. Researchers thus came to trace and study the homology one might observe within elite cultural production between the ordering principles and structures of authority of Greek and Roman cults and the political communities in which they found life. What is more, work in this vein regularly stressed—quite rightly—the extent to which the performance of cult penetrated the structures of everyday life: there was no sphere of one’s civic or familial existence outside religion, nor did religion offer space or forms of authority or systems of knowledge from which to launch an immanent critique.10

John Scheid has played a major role in all these developments over the past thirty years. In part this results from his extraordinary technical expertise across the full range of subdisciplines within classical studies, and his use of those skills in the study of the cult site and inscribed records of the Arval Brethren, a priestly college active in imperial Rome. In consequence of Scheid’s mastery of this material, his monograph on the cult of Dea Dia, the goddess venerated by the Brethren, and the social, political, and material contexts of the institutionalization of the Arvals, is perhaps the most fully elaborated study now in existence of an ancient cult as it was conceived, developed, practiced, and sustained. What is more, his careful theorizing about the rules and meaning of Roman ritualism, developed out of enormously detailed engagements with the data, must stand as paradigmatic for what can be achieved by this method.11

For all the rigor of its method and proper regard for historicism at its core, the theory of polis-religion and civic cult has never actually been hegemonic in the field.12 Although dissent and revision now proceed along a number of lines, no one has done more to provoke concern about the explanatory reach of the theory than John North. Commencing in 1979, North urged that the varieties of religious activity visible in the evidence already in the second century BCE could not be captured and explained by the theory. Focusing on the suppression by Rome of Bacchic worship, North urged that the action taken by state authorities could not be explained other than by postulating an awareness on their part of forms and spaces for religious activity that escaped not simply the actuality of their control but the form of their power. Never denying the prominence or importance of state cults, North has urged that we witness over time the development of a marketplace of religious choices, to which individuals repaired, sometimes in addition to their (at least nominal) participation in state cult, and sometimes instead.13

In recent years, critique of the civic model has developed a rich literature, some of which has been empirical, canvassing forms of religious activity that one can interpret as unaccounted for by the civic model. Greg Woolf’s “Polis-Religion and Its Alternatives” is a touchstone of this genre.14 Others have attempted theoretical engagements with the model and its expositors. The earliest and most trenchant articles in this vein were produced by Andreas Bendlin, and others have now taken up his misgivings about the notion of “embedded” religion.15 A number of scholars have advanced sociologically oriented accounts, of now startling variety. Some have taken up the metaphor of the marketplace and sought to explain large, long-term changes as aggregates of individual choices, susceptible to comparison with other similar historical developments. Here, a massive failing of the field overall has been its assumption that the one great historical change experienced by antiquity in the domain of religion was its Christianization, and a systematic flaw of a subset of the sociological literature is its employment of comparanda consisting in the spread of Christianity among other non-Christian populations.16 I have myself suggested that the phenomenon truly demanding explanation is not the conversion of the ancient world to Christianity, but its conversion to an understanding of self and religion in which “conversion” was meaningful; and I have attempted to provide a historical sketch of the dynamics that made this possible.17 Finally, still others are trying to reorient inquiry away from public authorities to households, and most notably to the individual as irreducible historical agent.18

This is the context in which Scheid seeks to intervene. Indeed, The Gods, the State, and the Individual should be understood as motivated by this turn in contemporary scholarship. It represents, at least in part, an intensive response to contemporary anglophone scholarship, and it deserves to meet that audience head-on. What is more, the debate now raging has all along existed in something of an echo chamber, because as influential as Scheid has been among experts, his work remains largely untranslated. That said, Scheid does more than attempt to diagnose some limitations of theory and method among critics of the civic model. He also offers a powerful and elegant restatement of major components of an orthodoxy that Scheid himself helped to bring into being. This translation thus provides a sustained account in English of an important position in historical research by its most prominent advocate.19

Regarding this translation, let me say a word about language and another about passages quoted by Scheid. The Latin term civitas and the French term cité are essential terms of art in Scheid’s text. The primary meaning of civitas is “citizenship,” it being an abstraction from civis, “citizen.” By metonymies standard in the classical period, it could also designate the collective that shared citizenship and was united by it—namely, “the people” of a given polity. It could also refer to the urban center that housed the political, legislative, and juridical institutions through which that people governed itself: civitas as “city.” And it could refer to the territory in which that people resided: civitas as “territory” or, perhaps, “state.”20

French cité occupies a correspondingly important role in Scheid’s text. The primary meaning of cité is, of course, “city,” but its metonymic and associative reach is quite different from English “city” and much closer to Latin civitas. For example, cité is the term commonly employed to translate English “city-state,” meaning that it can render civitas in those contexts when civitas refers not simply to an urban center but to the totality of territory on which a given political collectivity resides. Likewise, droit de cité (literally, “right of the city”) is a term of art in French and particularly Swiss citizenship law designating not simply one’s status as a legal resident of a given city; in many contexts it forcefully implies the possession of citizenship that follows upon legal residence within a constituent polity of the national state. Hence, although their patterns of association have different centers of gravity, Latin and French concepts in these lexical complexes map each other much more closely than any set of English terms can map either of those languages. In correspondence, Scheid has suggested that one render cité as city-state wherever possible, and I have followed that suggestion.

Scheid quotes texts from Greek, Latin, and German, nearly always in French translation. In every case—including, of course, texts whose original language is French—I have provided translations into English. Where possible, I have made use of published translations, but often enough I have had to prepare my own. In a single case—namely, the discussion of Foucault in chapter four—I have provided references to, and quoted from, works of Foucault and Paul Veyne beyond those cited in the French edition of this book, in an effort to clarify both what was at stake for Foucault in the remarks quoted by Scheid, and likewise the import to be assigned to Veyne’s reading of Foucault in the work cited by Scheid.

In closing, let me thank John Scheid for his cooperation in reading the English text and discussing several problems of translation. I am grateful also to the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study, where I read the copyedited text.