Читать книгу Operation Lavivrus - John Wiseman - Страница 6

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

For a man who had had less than two hours sleep, Tony looked remarkably alert. Settled well down in the driver’s seat but with his head erect, he overtook the slower motorway traffic with no apparent effort. His driving was smooth, anticipating what the other road users were doing. He looked as far forward as possible, dealing with things before they happened so they wouldn’t impede his progress. He checked his mirrors regularly, knowing exactly what was behind him. Although he was relaxed, he played little games that helped pass the time. He looked at car number plates and from the letters made up abbreviations.

He found driving gave him time to think and consider his life. The long line of lorries in the inside lane brought back childhood memories. As a kid he had wanted to be a lorry driver. His uncle would pick him up in the school holidays and take him on trips in a timber truck. It was an ex-army vehicle, and Tony thought his uncle had the best job in the world. He looked at all the trucks he was now passing, however, and didn’t envy the drivers at all. His dream of being a lorry driver was soon replaced by the urge to become a racing driver. At the house where he was born in South-East London, his mother had an upright mangle; for hours he would sit at one end and pretended the large cast-iron wheel was a steering wheel, controlling a Ferrari or Maserati.

The weak April sunshine favoured driving: visibility was good and the traffic light. Contrary to the weather forecast it was dry at present, but clouds were building up and the dark sky ahead looked ominous.

Tony was dreading having to use the wipers because he knew the washer bottle was empty. Due to the early morning start he was pushed for time. The lifeless form beside him was partly to blame for this. All the dirt on the screen would just get smeared if the rain was light, and he hated driving if his vision was impaired.

Although the sun was welcome it could be a nuisance. It was in his eyes when he was heading east to London in the morning, and again as he returned west towards Hereford in the afternoon. He had lost his sunglasses and refused to buy a new pair. ‘They’re for posers,’ he thought, tenderly rubbing his ear.

He started whistling ‘April Showers’, keeping it quiet to avoid disturbing his companion. He gave up after a few bars as his swollen lips couldn’t form the notes properly. He took a swig from the water bottle he had beside him, trying to lubricate a mouth that tasted like the bottom of a baby’s pram.

A lot had happened in the past three weeks, and Tony started reflecting on recent events. Three weeks ago the entire regiment was assembled in the Blue Room. This was a converted gun shed and the only place big enough to accommodate everyone. It echoed with the sound of many voices trying to work out what this gathering was all about. The din ceased abruptly with the appearance of a tall, authoritative figure who stared fiercely at his audience. When he was finally satisfied that he had everyone’s attention, he began speaking.

‘Gentlemen, at 0830 hours this morning a large force of Argentinian marines invaded the Falkland Islands.’ The Colonel went on to explain how this affected the nation and what they were going to do about it. Most people in his audience didn’t have a clue where the Falklands were. Some thought they were off the coast of Scotland.

Since this briefing A and D Squadrons had been despatched southwards to assess the situation. Tony had watched their departure with envy and was wondering when his turn would come. Rumours spread faster than dysentery at times like these.

A loud rumbling noise caused by running over cat’s-eyes brought Tony back to the present. The repeating vibrations transmitted up the steering column went through his shoulders to his neck, causing his head to shake and reminding him of the fragile condition of his head.

After a heavy night in the club he was wishing he had taken the soft option and had an early night. He was grateful that the three-hour journey was mainly on motorways and his partner could drive the return leg.

At present, however, the guy slumped in the seat next to him wasn’t any use to man or beast. His breathing was slow and deep, broken only occasionally by a loud snatch for air. This happened every time he forgot to breathe, which became more frequent the longer he slept. Contorted as he was, tangled up in the seat belt in a foetal position, it was a wonder he could breathe at all. A road atlas lay open on the floor with its pages crumpled under a pair of well-worn chukka boots, carelessly discarded. These emitted a strong smell of mature feet, intensified by the efficient heater. But the smell, instead of offending Tony, gave him a sense of security, knowing he had a comrade close by. As much as he would like to relax like his passenger, he opened the window to let in fresh air.

Yesterday afternoon he had played rugby, and he was now feeling the after-effects. His ears were so tender that he could hardly bear to touch them. This was the main reason why he didn’t open the window more often – the inrush of air was too much. They still bore traces of Vaseline because of their tenderness, and they had gone untouched in the shower. A fly had mysteriously appeared, and buzzed around the interior of the car; Tony thought, If it lands on my ear, it’s war. The tenderness of his ears was another reason Tony didn’t wear sunglasses. One ear was split along the entire length of the outer fold, and the other was ripped where it joined his head, distorted by trapped blood so it looked like a piece of pastry thrown on at random by a drunken chef.

He favoured his neck, carrying his head in a fixed position with his strong chin tucked in. When he wanted to look sideways he pivoted the whole of his upper body, trying to avoid any stress on his neck. His eyes pivoted in their sockets as he constantly checked the mirrors – offside, nearside, interior. From time to time he also checked on his lifeless companion, wondering with consuming jealousy how he could sleep so innocently. Every now and again he would try rotating his head, keeping the chin tight to the chest, but the pain and the gristly grating forced him to stop.

The snoring went on uninterrupted, regardless of Tony’s frequent glares, and although he had played in the same team his friend didn’t have a scratch on him. This rankled Tony because he was a forward who fought for every ball, taking the knocks so he could pass the ball to the backs. His work at the coalface went unnoticed, but the backs were in the spotlight, sprinting up the touchline with the encouragement of the crowd. Tony’s companion was the product of a public school where rugby was more of a religion than a sport. His handling and speed would get him a start in most teams: he was a fine player, and yesterday he had scored two tries seemingly with almost no effort. He was always in the right place at the right time, another sign of a good player. Tony’s first love was football, and he didn’t play rugby till he was in the army. ‘Typical!’ Tony thought. ‘Here I am, battered and driving, while fancy pants is sleeping like a baby.’

Apart from the discomfort he was happy. The build-up training was going well, and the rugby match, although intense, was light relief from all the night exercises, tactics and skills training that his squadron was engaged in. Inter-squadron games were normally banned because of the high casualty rate. Victory made the pain more bearable, and he smiled to himself as he remembered the looks on the other team’s faces when the final whistle blew. The slumped figure next to Tony had played a big part in the win; they started as underdogs, but surprised everyone by lifting the Inter-Squadrons Rugby Shield.

Traffic was building up as they skirted the capital, and Tony noticed how aggressive the drivers were compared with Hereford. Everyone changed lanes, often without any warning, and glared when the same was done to them. Tony just smiled and mixed it with the best of them.

‘This should be an interesting visit,’ he thought, looking forward to meeting the boffins at the research establishment where they would arrive shortly.

Tony Watkins was thirty-four and had been in the army for sixteen years. He joined the Paras initially, and couldn’t stay out of trouble. When he signed on at Blackheath he had never heard of the SAS, as few people had.

As soon as he started his basic training with the Paras in Aldershot, Tony realised he had made a big mistake. The Paras were definitely not for him. His sense of humour and loathing of discipline didn’t go down well with the staff of Maida Barracks. Things didn’t get any better when he was posted to a battalion; in fact they got worse. He was super-fit, a natural athlete, and enjoyed all the physical stuff, but all the bull was like shackles around his body. Cleaning, sweeping and polishing were not for him. He had to get out.

Salvation came in the form of a soldier who was in transit from the SAS, just returning to Malaya after inter-tour leave. Tony got talking to him and was introduced to the Regiment. He soon became mesmerised by their exploits in the jungles of Malaya. Tracking down the bad guys, living in swamps and parachuting into trees – that was more to his liking than cleaning dixies and picking up leaves.

Selection for the Regiment was tough, but Tony loved every minute of it. Six months flew by. He had finally found a use for his endless energy and was soon recognised as an outstanding soldier. It was an individual effort, and he soon learnt self-discipline. This helped him to control a quick temper and think before reacting. As a kid he was too keen to lash out at anyone who upset him.

After his tough upbringing in South London he found the life easy. He tackled all the training with a passion, excelling at everything. Promotion came fast, and he was already the troop staff sergeant of 2 Troop A Squadron. The intense regime of regimental life was natural for him; he wouldn’t change it for anything. 2 Troop was the free-fall troop, and they prided themselves on being the best and fittest troop in the Regiment.

Signalling early, Tony pulled into the nearside lane and turned off the motorway. The silky-smooth V8 engine of the Range Rover pulled strongly as they climbed a steep road cut in the side of a chalky hill. The scarred white landscape was evidence of a road expansion scheme, and the volume of traffic justified this. It was all heading to London, two lanes bumper to bumper, with most cars having only a solitary driver in, usually with a face longer than a gas-man’s cape.

Near the top of the hill was a slip road that led to the main entrance of Fort Bamstead. Tony slotted in between the slow-moving trucks and turned off.

The establishment nestled around the hill, sprawling down a deep gulley. It was screened by trees and shrubs, with no signs to advertise its location. The locals had long forgotten its presence, and were not aware that some of the best brains in the country worked here. Rows of majestic oaks lined the lane on both sides, and the unusually large silent policeman caught Tony out. He was looking for hidden cameras and hit it going too fast, causing the vehicle to shudder. He took more care when he reached the next ramp, but at least he got a reaction from the living dead lying beside him.

Stirring for the first time, the crumpled figure alongside Tony started to sit up. He opened sticky eyes, running his tongue over dry lips. His mouth opened wide in a yawn that Tony had to copy. He stretched slowly, unwinding to his full length with arms extended above his head, playfully pushing Tony on the shoulder. ‘Here already, Tony? That was quick.’ He yawned again and ground his teeth, using his tongue to search his mouth for moisture.

Tony stopped in front of a pair of heavy iron gates, waiting for someone to come out of the guardroom on the right. His companion was still yawning and sorting out his footwear. It took ages before a uniformed figure appeared, clipboard in one hand and pen poised in the other. The policeman marched smartly towards them, bracing himself against the freshening wind. He looked through the gate, comparing the vehicle’s registration number with the memo on his clipboard, before finally saying, ‘Park your vehicle over there,’ indicating a large lay-by, ‘and bring your ID to the window over there,’ nodding towards the building. He noted down the time, skilfully using the wind to keep the pages flat.

‘You’re not looking your best this morning, Tony,’ his passenger commented.

Tony had to bite hard on his tongue. He had been driving for three hours while Peter, his passenger, slept. ‘It’s all your fault, Pete. I was ready to turn in at midnight, but you had to order another bottle.’

Ignoring the arguing couple, the policeman fumbled with a large bunch of keys to open a small side gate before scurrying back to his warm refuge like Dracula at sunrise.

Ministry of Defence policemen all come out of the same mould. They are usually ex-servicemen with an exaggerated military bearing, sporting a regulation short back and sides, with a small, neat moustache. If they have a failing it is for being too officious, and a reluctance to be parted from their kettle and electric fire.

Tony said, ‘You stay and rest, Pete, while I go and sign us in.’ As he walked towards the window it was second nature to examine his surroundings. He noted the closed-circuit cameras and the powerful spotlights. The close-linked security fence with razor wire on top brought back some painful memories. On many occasions he had spent time climbing and cutting it, trying to avoid its painful spikes.

A portly sergeant with a clipped moustache, displaying two rows of colourful medal ribbons, greeted him at a window. ‘We’ve been expecting you, sir. Just fill in these passes while I phone Dr Jenkins that you’re here. Your mate will also have to come and sign himself in.’

Tony left the policeman, who was busying himself with an internal phone list, holding it at arm’s length. He returned to the car where Pete was still sorting out his footwear and swigging water at the same time.

‘Sorry to bother you, Pete, but when you have finished destroying my map you’ve got to sign yourself in.’

Peter was four years younger than Tony, and apart from a haggard expression he looked remarkably fresh. No matter what he wore or did, he always looked smart and clean. Eventually, satisfied with his footwear, he found his jacket amidst the carnage of the back seat. He climbed out the car to join Tony, who was waiting impatiently, wondering what he had done to deserve having to play nursemaid. As they walked towards the guardroom Pete’s close-cropped hair was unaffected by the wind, and although his leather jacket was crumpled he still looked as smart as a tailor’s dummy. He moved with athletic grace, his well-proportioned body and fine features radiating power and arrogance.

The pair were surprised to see the sergeant still on the phone and were alarmed when he hung up and refocused on the telephone list. He had his glasses on now, and studied the list intently. Tony felt like ripping the list from him but thought better of it. He could almost read the figures from where he stood. Pete sheltered behind Tony, casually leaning on the wall thinking how well a cup of tea would go down.

‘Sorry for the delay. The doctor wasn’t in his office. We finally found him and he’s sending his assistant to fetch you,’ said the sergeant as he polished his specs and held them up to the light for inspection. ‘I’ll open the gates so you can come through.’

Visitor passes were issued and the gates opened. Usually all vehicles were left outside, but this one had special dispensation. A young woman in a crisp white coat came to meet them, and Pete’s face lit up as they introduced themselves. He settled her in the middle seat of the car and spent a lot of time helping her with her seat belt. Her perfume was a welcome addition to the heady atmosphere of the vehicle, and she directed them to a remote area of the camp where three portacabins were sited. Each had a large generator parked outside, feeding the cabin with a mass of cables of various thicknesses.

The portacabins were unique. They had no windows and were lined with wire mesh. This was to ensure that no radio signals could enter or escape . Pete was too busy talking to the girl to notice, but Tony took it all in.

‘Ah, Captain Grey and Staff Sergeant Watkins, so glad you could make it.’ A tall man in his sixties with an unruly mess of thinning white hair and equally untidy eyebrows met them at the door and shook their hands vigorously. The white coat he wore was covered in small burn holes, and his top pocket was stuffed with spectacles and an assortment of pens. His identity pass was pinned on the other side, displaying a picture of a younger man.

‘Tea or coffee, gentlemen? How do you take it?’

Tony ordered for the pair of them. ‘Both tea just with milk, please.’

Dr Jenkins turned to the young assistant, and in his thick Yorkshire accent requested, ‘Two teas, Susan. Standard Nato.’

The interior of the cabin was well lit by an unusual number of ceiling lights. Down each side were benches loaded with display screens, meters and soldering irons. Each bench had a rack containing rolls of multicoloured wires of variable diameters, with little square storage bins containing nuts, bolts and washers stacked at the back.

‘Sorry for the delay at the guardroom, but we cannot have telephones in here. The whole cabin is screened so we get accurate readings, and nothing can influence our delicate electronics.’ He led them past a maze of cables and dexion cabinets, stopping at a large, untidy bench. Kit had been brushed aside to make room for a tube of aluminium twelve inches long and two inches in diameter. The untidy pile of tools, heaped boxes of grub screws and meters formed an amphitheatre around the tube, giving it presence. This is what they had came to see.

Standing close, with blobs of solder and wire snippets underfoot, they looked down expectantly. At first glance they were slightly disappointed at the unassuming-looking object, expecting something more elaborate, thinking, Could this object fulfil our requirements?

‘This, gentlemen, will stop us losing the war.’ The doctor picked up the tube with loving care and started explaining its virtues. Once he got going it was hard to keep pace with him. He went into great detail describing the difficulties that had to be overcome and the amount of work that went into producing the innocent-looking cylinder.

‘The frequencies involved were in the 3 to 4 Hz band . . .’ Peter sat down on the only stool available and Tony leant on the bench, trying to follow the technical jargon. ‘Reducing the circuitry so it would fit inside the dimensions you gave me was the greatest challenge I have had to face in my forty years in this establishment.’ Scarcely pausing for breath, the doctor hurried on. ‘The coaxial condenser needed to be compatible with the zynon 3-mm . . .’ He spoke mainly to the cylinder only, occasionally looking up at the bewildered couple. ‘. . . tredral activator.’

Peter sneaked a look at Tony, searching for evidence of understanding. Their eyes met, forcing them to exchange a huge grin as the doctor continued to baffle them. There was a momentary pause as the tea arrived, and the heap of kit was further rearranged to make way for the mugs and the plate of biscuits.

‘To put it simply, gentlemen, if this device is placed in the correct position it will do everything you have asked me to achieve.’ Even a mouthful of chocolate digestive couldn’t stop the flow of information. A spray of crumbs now accompanied his briefing. ‘It is turned from a solid block of aircraft-grade aluminium. Virtually indestructible. . .’ At last he stopped for a swig of tea. ‘Any questions?’

‘How is it powered, and how long will it last?’ asked Tony.

Thoughtfully the doctor drained his cup before answering, fondling the tube obscenely. ‘To put it simply, it operates like a self-winding watch. Any movement will charge the circuits that lie dormant when motionless. There is an oscillating trembler switch. The whole tube is filled with epoxy resin. This protects the circuits and components, making them virtually indestructible. They’re not affected by vibrations or G force. The end cap has a 3-inch fine thread and is bonded with a heated adhesive when screwed on, making it stronger than a weld. Once sealed it cannot be opened.’

‘What about the effect of climate? What is its operating range?’ asked Tony. Now that Susan had joined them, Pete seemed less interested in the device.

‘The coefficients of all the materials are compatible within a micron. We have heated it in an oven for twenty-four hours and had it in a deep freeze with no adverse effect. The resin has a melting point of 3,000° Celsius and a freezing point that we cannot determine in this laboratory’.

‘If it’s sealed, how do we turn it on?’ queried Tony.

‘In here is a transponder that activates when it receives a signal. It powers up all the circuits. These are duplicated just in case one fails. Two micro-capacitors . . .’ and so it went on.

‘Can I hold it, please?’ The doctor hesitated slightly before handing the tube over. ‘What’s this arrow for?’ queried Tony, pointing to a small engraving at one end.

‘Ah, that’s to ensure that when they are in transit all the arrows face the same way to ensure that they will not become accidentally excited or activated. I will enlarge on this later.’

‘Now for the million-dollar question: How do we fix it?’ asked Tony. Pete still seemed keener to talk to Susan than the doctor. ‘Feel the weight of this, Pete.’ He handed over the device, trying to get him interested and include him in the conversation.

‘Follow me.’ The doctor led the way to the back of the cabin, where a scaffold pole was held in a vice clamped to a bench. Holding the device two feet from the scaffold pole, he continued his briefing. ‘The inside of the cylinder is lined with a multiple layer of ceramic magnets. We borrowed this idea from the space chappies at NASA. Just watch as we get closer.’ He inched the device nearer to the pole, building up the tension like a music-hall entertainer. ‘Look at it now.’ He gripped the device in both hands, and as it got within three inches it started shaking. At less than an inch he let it go; it leapt the gap and firmly clamped onto the pole. ‘There we go: snug as a bug in a rug. Try to prise it off,’ he offered.

Tony and Peter took it in turns to try and remove the cylinder, and only succeeded when they worked together.

‘That’s amazing,’ said Peter. ‘I’m really impressed.’ They both stood there thinking the same thing: This is all too good to be true. It is so simple there must be some drawbacks. They were both experienced in the use of modern technology, and wary of it. It was great when it was working, but anything that can go wrong usually does, especially when the pressure is on. Simplicity is the key, and this device, although very sophisticated on the inside, was simplicity itself. They were both lost for words trying to think up snags or shortcomings.

The doctor left them to their thoughts and gave them time to discuss things between themselves. He retired to the first bench and opened a drawer, removing a sheath of papers. ‘Is there any tea left in the pot, Susan? I could murder another cup.’ With his glasses balanced on the end of his nose he looked every inch the mad professor. He shuffled a pile of forms and papers, occasionally writing in a notepad. He wrestled with sheets of carbon paper, and kept dropping them on the floor. As he stooped to pick one up he would drop his pen; he spent a lot of time arranging the paperwork to his satisfaction.

Susan returned with a tray full of fresh tea and Peter needed no second invitation to join her at the bench, leaving Tony deep in thought, still playing with the cylinder. While the doctor was recovering a piece of paper from the floor he found a small grub screw. ‘Do you know I looked everywhere for this?’ he exclaimed.

Tony joined them and handed over the cylinder. ‘Come on, doc, there must be some snags. This looks all too simple.’

‘The only snag or drawback as I see it is accurate placing. Because of the size limitations everything is minimal, and proximity to the signal source is paramount.’ As he spoke he rhythmically tapped the device in the palm of his hand. ‘I believe you are now going on to Shrivenham where they will advise you on placement.’

‘Yes we are due there this afternoon,’ replied Peter. ‘Everything is happening at once.’

‘I have got the paperwork sorted. This is the hardest part of the project for us. I am well over budget and have used up the entire department’s overtime allowance. I would rather go with you than face those paper-pushers over the road. What about you, Susan?’

Before she could answer Pete chipped in, ‘We would love to have you along.’

‘Susan, can you put this one with the others, please.’ The doctor handed over the aluminium cylinder. ‘Gentlemen, the only thing I can add is that you must ensure that in transit you have all the arrows facing the same way. We have tested the device thoroughly in the laboratory, but to a very limited extent in the field. We just have not had the time. What do you think, Captain? Will it do?’

Peter’s gaze followed the girl as she walked to the door and busied herself packing away the device with all the others. He noticed the absence of make-up and the neatly swept-back hair. There was a pregnant pause as the doctor waited for an answer.

Tony came to the rescue. ‘Thank you for all your help, Doctor. We certainly didn’t expect you to come up trumps so quickly.’

A sly dig in the ribs got Pete’s attention and he took over. ‘Yes, thank you very much. It is now up to us.’

‘We wish you the very best of luck. Sign here for the thirty-six devices, and again on the bottom of the pink form. Let me sign your passes and remember to surrender them at the gate.’

Tony backed the vehicle up to the cabin and loaded the boxes while Peter chatted to Susan. ‘Come on, you old Tom,’ he called out. ‘We must be going. The wife and kids will be missing you.’

It was Pete’s turn to drive. ‘Did you see her eyes? They were lovely.’ He jumped hard on the brakes to slow down for the sleeping policeman.

‘Why is it that every time you meet a woman you fall in love, and why is it that every time there’s work to be done . . .’ The two argued good-naturedly for several miles, with Pete discussing the girl and Tony the device, before lapsing into silence. They were heading back west but had a short detour to make which would take them to the Royal College of Science, Shrivenham. Tony tried to sleep but Peter thought he was driving his Caterham 7, and was throwing the car around with gay abandon. Tony gave up the idea of sleep and concentrated more on survival. Finally he broke the silence. ‘What do you think?’

They instinctively knew what the other was thinking; they had been working together for two years and a special bond had been forged between them. They understood each other’s moods and fancies, knowing when something wasn’t quite right. When troubled Pete tended to lapse into long periods of silence, mulling things over and keeping them to himself, whereas Tony did the opposite and liked talking about any problems as he attempted to work them out.

‘Well, they certainly have done their homework. I was expecting a bloody big box with switches on.’

‘Considering how little time they had, they’ve worked miracles. It’s a pity there are no practice devices. I don’t like the idea of training with the same ones we are going to use on ops.’

‘The man said they’re indestructible, but he doesn’t know the lads. We could lose them, especially when parachuting, and there are no replacements.’

‘I think we only use them on the target attack phase, and not the infiltration.’

They discussed the best way to train with them, considering the alternatives. Tony tried to keep Peter engaged in conversation as he didn’t drive so fast when he was talking. When they lapsed into silence Pete would speed up and the scenery would flash by. They turned off the motorway onto a narrow country lane, and Tony was thrown around too much for his liking.

‘Do you remember them knock-out drops in Borneo?’ he asked.

Peter didn’t answer straight away as he came up fast behind a pick-up truck. He didn’t check his speed but accelerated past just as they were entering a left-hand bend. Tony’s foot stamped on an imaginary brake pedal with both hands gripping the dash, his eyes out on stalks scanning ahead. His worse nightmare happened: a car appeared, closing the distance rapidly. There was nowhere to go, thick hedges on both sides laced with large tree. A crash looked inevitable.

With less than inches to spare, Pete passed the truck and pulled back in, ignoring the fist waving and flashing lights from both vehicles.

‘No. What drops?’ he asked coolly.

Tony couldn’t speak – in fact he couldn’t remember the question – and when no answer came, Pete enquired, ‘Hungry, mate? Let’s stop at the dog stall for a sarnie.’

Tony stared intently at Peter, nursing the circulation back into his hands. The last thing he wanted at that moment was something to eat. When the crash seemed inevitable all he wanted to do as his last gesture on earth was to punch the driver as hard as he could. He was still fighting for composure. All of his ailments and discomforts had temporarily left him, but now they returned with a vengeance. His ears and lips throbbed, and a bout of cramp gripped his left calf. He thought to himself, ‘Wait till I get out he vehicle . . .’ but he actually said, ‘There’d better be a toilet handy.’

After a short break and all essentials had been catered for, they arrived at Shrivenham and went through the same routine as before. Security was more obvious here, but the same monotonous procedures were followed.

Eventually they were guided to a large hangar, where they were greeted by a lively, fit-looking man wearing a Royal Signals cap badge.

‘Hi, chaps. I’m Captain Charles Minter. Come on in. Please call me Chas. Toilets to the right, and my office is the last on the left, at the far end.’

He shook their hands warmly, pointing down a long bare brick corridor painted in a sickly green with polished brown lino covering the floor. There were many doors on the left-hand side, but only one large double door on the right. They followed the captain down the corridor, declining the offer of the toilet. All the doors were identical, varnished in dark oak with a frosted glass panel at the top. He stopped and opened the last but one door. Balancing on one leg, he stuck his head around the jamb and ordered, ‘Tea for three, Mary, and could you possibly round up some biscuits?’ Some things never change; the army thrives on its tea, and rarely goes an hour without a brew.

They went next door into the captain’s office, which looked more like a museum than a place of work. It was well lit, with two large windows giving a view over open fields. Each had a pair of cheap printed curtains hanging forlornly from large brass hooks, many of which were missing. The floral design was faded, giving the curtains the look of badly stowed sails on a battered yacht. Above one window was a line of regimental plaques, adding a splash of colour. The other two walls were smothered in photos and maps. In places they overlapped, making it hard to see the lime-green emulsion underneath. The grey filing cabinets were smothered in stickers from all the three services. Different squadrons, ships and regiments were represented. One sticker in particular caught Tony’s eye: ‘Paratroopers never die, they just go to hell and regroup.’ Even the desk was covered in militaria, and a conducted tour was needed to explain the models, badges and assortment of ammunition that lay there. Under a layer of transparent plastic were more photographs, and heaped at the back a pile of bayonets and knives. Not even the telephone or the wastepaper basket had escaped from the stickers, and when the tea was brought in by a middle-aged lady, wearing a brown tweed skirt and blue woollen twinset, the cups bore RAF squadron logos.

‘Thank you, Mary. If you set it down over there.’ Chas dropped a pile of maps on the floor to make room for the laden tray on top of a bookcase crammed untidily with books and magazines.

Pete and Tony were looking around the office, thinking they had seen everything, then something else would catch their eye. Chas removed a climbing rope from one chair and a pile of pamphlets from another. He gave the inquisitive pair a few more minutes, then invited them to sit down.

‘I think we have a mutual friend: Jimmy Thompson,’ suggested Chas.

‘Yeah, that’s right. Jimmy’s running Ops Research. He was going to come with us but got called away last night. I’m Tony Watkins, and this is Peter Grey. We are both in 2 Troop and have just came from the Fort.’

They exchanged pleasantries over the tea, and Chas was only too pleased to explain a lot of the paraphernalia that littered his office.

‘This round here never went into production; it was too expensive. This blunt-nose shell came from Iran and can penetrate . . .’ He went on for a good twenty minutes, holding the pair’s undivided attention. Although they were fascinated, however, they were on a tight schedule, and Tony had to take an exaggerated look at his watch to break the spell and get Chas back to the reason for their visit.

Carefully resheathing a bayonet, he laid it back on his desk. ‘That’s enough of my toys. Let me fill you in on yours. I don’t know how much of the background you are aware of, so stop me if you’ve heard it already.’ He made himself more comfortable before continuing.

‘Your Director was asked by the War Office to come up with a plan to protect the Task Force from air attack. He requested our assistance four weeks ago, regarding the menace posed by Exocets. These have been responsible for sinking three of our ships already. Working closely with RARDE, where you have just come from, we had to come up with a solution for stopping these air attacks on our fleet. If we don’t succeed we won’t have a Task Force left. We cannot afford to lose any more ships; this would seriously endanger our invasion plans. Argentina have some very useful pilots and in the Super Etendards a first-class aircraft.’ He paused while he went to the bookcase and selected a large book before settling back in his seat.

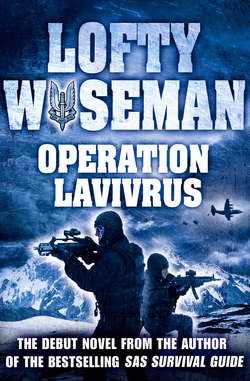

‘It’s not just a matter of you chaps going in and blowing the aircraft up. It’s got to be more subtle than that.’ He looked at the pair intently. ‘Because of the fragile coalition with neighbouring countries any assault on the mainland would be taken as an escalation of the war, and we would lose their support. So we have come up with “Operation Lavivrus”.’

He opened the large book on his lap, entitled Jane’s Aircraft Guide, and selected a double-paged pull-out picture of an aircraft that looked menacing even on paper. ‘This, lads, is the Super Etendard. Are you familiar with this aircraft?’

‘I know it’s French and I’ve seen one at Farnborough,’ replied Tony, ‘but that’s all.’ Peter merely nodded and studied the picture before him.

‘Yes, it’s a French strike fighter made by Dassault-Breguet. It’s an old design, but modified extensively. They have a carrier-borne capability, but so far have all been based ashore. It has a new wing, fitted with double slotted flaps, with a drooping leading edge. This is mounted in the mid-fuselage position and swept back at 45 degrees. The tricycle undercarriage is uprated with long-travel shock absorbers for carrier operations.’ All this was reeled off without a glance at the book or reference to any notes. The captain was full of nervous energy and was in his element. ‘The nose wheel is of special importance to you, and we will look at one in the hangar later. The new Atar 9k50 turbojet gives this aircraft an impressive performance: 733 m.p.h. at sea level, 45,000 feet ceiling and a operational combat radius of 528 miles.’

He propped the book open on the desk and used an old whip antenna as a pointer. He indicated different components as he introduced them, tapping the book for emphasis when required. His enthusiasm was infectious, holding the pair’s attention.

‘The armoured cockpit is pressurised and fitted with a Martin Baker lightweight ejection seat. They are all single-seaters, and this is a weak point. With all the sophistication of electronic counter-measures, inertial navigation and weapon systems, it puts too much strain on one man. A second man is desirable. The fuselage is an all-metal semi-monocoque construction, with integral stiffeners. The wings are attached by a two-bar torsion box covered by machined panels.’ A thin bead of sweat formed on his brow, but nothing slowed him down. ‘Now all aircraft are vulnerable on the ground, and you know more about this than I do, but there are several options that we looked at. Considerable damage can be done with a hammer, but this takes too long and is noisy. Obviously explosive does a complete job; it destroys the aircraft, and a timed delay allows the intruders to escape. But what we are trying to achieve has never been done before. We are going to mess with their weapon-aiming systems without the Argies knowing.’ Chas paused to gauge the reaction from his audience.

Tony reflected back to the day he was summoned with Peter into the Ops Room in Hereford and told of the planned incursion onto Argentinian soil. The aim was to neutralise the air threat to the Task Force. The whole operation had to be deniable, which was a contradiction in terms: How could you destroy the threat without leaving any evidence?

The plan was to attack the Super Etendards at their base, not with explosives but with an electronic gadget. To a soldier this was hard to comprehend; he likes to see a mass of burning metal, knowing his job is successful. To infiltrate and leave a device that still allows the aircraft to fly was against his instinct. These electronic devices were untried and involved all the dangers of placement but without the guarantee of success. If they didn’t work there was no second chance.

The operation had to be completely deniable as the British Government would be politically embarrassed by such a venture, and the world would see it as an escalation of the conflict. America had warned of the severe consequences of an invasion of the mainland. Countries sympathetic to Argentina, and those on the fence, could well join the war against Britain.

Captain Minter closed the book and offered them a cigarette. ‘Smoke, anyone?’ he said, offering them a packet of Capstan Full Strength. They both declined, deep in thought as they appreciated what a complicated mission they were engaged in. ‘I didn’t think you would. I’m trying to give up myself,’ he said, flicking open a Zippo lighter with a Special Forces logo on the sides; with a deft flick of the wrist he produced a two-inch flame and lit his cigarette. The resulting clouds of smoke brought the room alive. His desk now took on the look of a battlefield. Tony became agitated and backed away from the smoke, and Chas made a circular motion of his arm, trying to dissipate it.

‘We’ll go in the hangar shortly. It’s a non-smoking zone.’ This was his last chance of a puff, and he was taking full advantage of it. ‘Is there anything I’ve missed?’ he asked, tapping ash into an ashtray made from an artillery shell.

Tony coughed politely into a balled fist and asked, ‘What are the chances of getting away with it? Won’t they get suspicious if they keep missing and find the device?’

Chas answered through a curtain of smoke, exhaling forcefully. ‘Good point, Tony, but the clever thing about the placement is that on the ground it is nowhere near the weapons guidance system. You will see shortly how well it fits in position, and unless they have to service the nose wheel assembly it will go unnoticed. As for the missiles going astray, they will probably think we have developed a new counter-electronic measure. The device is completely passive until activated by the aircraft; it’s not switched on till the aircraft switches on its target acquisition radar.’

He opened up the book again to display the aircraft pull-out, and pointed. ‘The device is planted here on the nose wheel, and it’s only when the undercarriage is retracted that it comes in close proximity to the guidance system. They can only check the aircraft on the ground, so I think we have an excellent chance of getting away with it.’

They both pored over the diagram, noticing the position of the bay that held the electronics of the missile guidance system. It was directly above the recess where the nose wheel was stowed when retracted.

‘You put it in the right place and we will do the rest,’ added Chas between puffs on a rapidly diminishing cig.

‘What about the missile itself?’ enquired Peter. ‘Do we do anything to it?’

‘We have an Exocet in the hangar to show you, and our man, Mr Ford, will brief you on this. He is not available till three, so we will look at the undercarriage first. But in answer to your question, no, you don’t touch anything else. Just place the device in the correct position, and everything else is history,’ he said dramatically, stubbing out the remains of his cigarette. ‘Follow me, gents, and let’s see what we’ve got.’

They retraced their steps down the corridor and went through the large pair of double doors into the hangar. It was a massive structure illuminated by endless rows of fluorescent lights hanging down on chains from the cross-girders that supported the steeply angled roof. The walls were of red brick, giving way to corrugated sheeting at ceiling height, with a pair of huge sliding doors at the far end. The sheeting was painted in a fresh green colour, giving the vast area a pleasant, light atmosphere. The floor was painted red, and in neat rows, as far as the eyes could see, were mortars, artillery pieces, missiles and tanks.

Not many people were allowed in this hangar, and Tony thought the public would love to see this display. It was the best in the country, indeed probably in Europe.

‘This is superb,’ commented Peter. ‘Who uses this lot?’

Chas was leading them to the right between a row of mortars and tanks. He stopped by a multi-barrelled mortar, resting with his left leg up on the base plate with both arms folded over the sights bracket.

‘Basically we study weapon systems here. We obtain weapons and equipment from all around the world and evaluate it. We strip it down, test it and fire it. Most of this kit here is Warsaw Pact, but we look at everything. Anything new, we procure and test.’ Tony and Peter could detect the satisfaction that Peter got from his job, and were impressed by his enthusiasm and knowledge. They felt like rats in a cheese factory.

‘Officers study here for their degrees. They have to write a thesis on a particular subject. Also a lot of research is carried out here and improvements are made to existing equipment. This mortar is interesting. We just acquired it from Afghanistan. It’s the only one outside of the Soviet Bloc. I think some of your chaps were involved with its procurement.’

‘What will you do with it?’ enquired Pete.

‘We will strip it down, look at the workmanship and design, then we will take it on the range and check it for accuracy, range, penetration and all that sort of thing. Then back to the workshop and strip it down again, testing for wear and strength, and also durability’.

‘Sounds interesting,’ enthused Tony. ‘I would like a job like that myself.’

‘There you go, Tony. Get a commission, sit for a degree, and you can,’ mocked Peter.

Tony went red, his anger mounting. ‘I don’t like it that much, Pete. Somebody’s got to look after you.’ This was said with venom, prompting Peter to quickly change the subject. ‘What’s that over there?’ he said, pointing to a large artillery piece.

They moved on, slowly making their way to the side wall where the front section of an aircraft was positioned. The nose of the aircraft as far back as the cockpit was mounted like a game trophy coming out of the wall. The sleek shape painted blue-grey was complete with nose wheel assembly, refuelling probe, pitot tubes and tacan navigation system.

‘Believe it or not,’ said Chas, ‘this whole assembly retracts up into that hole, and these flaps seal it. Remarkable engineering, eh?’ He was gripping the landing gear and pointing to the dark aperture above it. ‘This is it, gents, courtesy of Messier-Hispano-Bugatti. Have a close look; it must be imprinted in your brain.’

The nose gear consisted of a large tube of bright alloy, with a smaller tube of steel emerging from the bottom connected to two wishbones. A large squashy tyre was pinned between these, and four struts braced the large tube on all sides, disappearing up into the aperture. About two-thirds down the main tube were two smaller alloy cylinders that ran back at an angle, filled with hydraulic fluid. These activated the gear, and alongside these were two steering levers, each made of bright alloy.

‘Do you notice anything familiar on the gear?’ asked Chas. The two crouched and stretched, examining the assembly minutely.

Chas put his hand on the hydraulic cylinder where the steering arm was connected. ‘Have a close look here.’ From either side the two stooped for a better look at where Chas was pointing. Lying snug between the two was a third aluminium cylinder twelve inches long and two inches in diameter.

‘That gentlemen is our device. Try and remove it.’

The cylinder was so well concealed that the pair couldn’t get a good grip on the tube, and try as they might it never budged. ‘Imagine that with hydraulic fluid and accumulated grime on it,’ interjected Chas. It was a perfect fit and blended in superbly.

‘There are tremendous forces exerted on this gear on take-off and especially landings. That is why we have implanted the magnets. There are many metal components inside the alloy tubes, like springs and pistons, and these help keep it in position. What do you think? Could you position these in the dark undetected?’

‘If we are lucky enough to get this close I can’t see a problem,’ replied Pete. ‘We need to have a mock-up like this to train up the lads.’

‘We are lending you this complete mock-up. It’s going to be reassembled at your training area at Ponty tomorrow.’

‘I can see this area being very dirty, especially when they are flying on non-stop sorties, and this could be a problem if it leaves a bright cylinder amidst dirty, oily components. We will have to be careful not to leave any prints or signs of disturbance in the dirt either, which may alert them,’ offered Peter.

‘Try not to touch anything. Just place the device and maybe smear a little dirt on it which you can get from the main undercarriage.’

The trio were so absorbed discussing the problems that they were unaware of a fourth man who had quietly joined them. He stood well back with hands thrust deeply in the pockets of his well-worn corduroy trousers. A few remaining strands of pure white hair were brushed smartly back over a shiny bald pate. A neatly clipped moustache underlined a strong Roman nose, with a pair of large framed spectacles sitting low on the bridge.

‘You can see why the size is so important,’ remarked Chas. The two lads tried again to prise the device off, but had no luck with the stubborn tube.

The newcomer moved closer, standing braced with his hands still thrust deep in his pockets, ‘Having trouble?’ he asked.

Captain Minter turned suddenly, grinning hugely as he recognised the familiar figure of Mr Ford. He felt like a naughty schoolboy caught smoking behind the bike shed.

‘Ah, Albert. Just finishing here. Meet Tony and Peter.’

Peter attempted to clean his hands on the side of his jeans before shaking hands. ‘Please to meet you, sir. Peter Grey, and this is Tony Watkins.’

Tony returned the firm handshake, surprised by the strength of it. Albert was a retired engineer, having worked with British Aerospace for more years than he cared to remember. He now worked on a consultancy basis with the School, giving them the benefit of his vast knowledge of missile guidance systems. In complete contrast to Chas, his verbal delivery was slow, enriched by a strong Cornish accent.

‘Nice to meet you. I’ve heard so much about you lads. I was tickled pink to get so close to you unnoticed, and heard you whispering,’ he drawled.

‘It’s an old SAS habit. It drives the missus mad. Every time I do something delicate, like changing a light bulb, I whisper. Can’t help it. It drives her nuts,’ replied Tony.

‘I’m just the opposite,’ replied Albert,. ‘I have worked in noisy machine shops all my life and we tend to shout, but it has the same effect on the wife, though.’

Chas interrupted their banter on marital comparisons and said, ‘Albert, I have covered the placement of the device. Would you like to carry on and tell the lads how it works?’

‘Love to,’ replied Albert, taking a deep breath. ‘When the undercarriage is retracted it lies in this position.’ He indicated on the mock-up with a broad sweep of his hand. ‘It’s just above the pitot tubes and the tacan. The tacan relies on ground beacons, not radar. The pitot tubes feed the air data system with information like speed and temperature, and again they have nothing to do with radar or interfere with radio or radar reception. Now just here,’ he patted an area just below the front of the cockpit, midway down the fuselage, ‘sits the radar, and this feeds the missile guidance system, which enables the missile to hit its intended target.’

Albert paused to let the info sink in before resuming. ‘Once the missile is fired, this equipment illuminates the target, feeding all the necessary information to the missile, such as direction, height, range and speed. It keeps the target pointed with, for want of another word, a beam, which the missile follows. Now with our little surprise package in position,’ he pointed to device on the undercarriage, ‘this beam is bent. The pilot thinks the target is still acquired when in fact the beam is off to one side. The missile follows the beam regardless and hopefully misses the target. In layman’s terms, this device tells a pack of lies to the missile, just like a drunken man tells his missus when he returns home late from the pub.’

The silence that followed showed respect for the architects of such a scheme. Albert and Chas drew back to leave the soldiers with their thoughts and deliberations. For several minutes they were totally engrossed, running the scenario through their minds, searching for unforeseen hurdles. Finally they came to the same conclusion, and Tony was speaking for both of them when he said, ‘All we have to do is place it.’

Nicotine addiction finally got the better of Chas and he said, ‘I’ll leave you in the capable hands of Albert and meet up with you in the missile section. See you soon,’ and he disappeared outside for a smoke.

Albert led them through the maze of weapons to the opposite wall where impressive arrays of missiles were displayed. The exhibition represented the state-of-the-art weaponry required for hostilities on land, sea and air. Smaller examples were displayed on blanket-covered tables, with the larger ones housed in cradles on the floor. Some models were cutaways revealing complex circuits, sensors and guidance systems. They all had an explanatory plastic covered display card which gave the name and details of the missile. Under the bright lights they looked too polished and clean to be dangerous. Their sleek lines were a work of art belying their destructive qualities. This opinion was changed by the photographs displayed, however, as they formed the backdrop to each table, showing targets destroyed by these very missiles.

Albert ushered them to a large white projectile which had some bold lettering stencilled on the side. As they got closer the word AEROSPATIALE leapt out at them. When he spoke he tended to favour Tony, so Pete felt a bit left out. He wondered if he reminded Albert of a rebellious son. To gain favour, Pete read out the title on the display card, ‘AM39, EXOCET’.

‘Yes, gentlemen, this is the anti-ship missile, weighing 652 kilogrammes with a high-explosive warhead of 160 kilogrammes. It flies at wave-top height with active radar terminal homing. This is what we are going to lie to. This is the nasty thing that has been causing all the trouble.’

They had a good look at the dart-like object, imagining its performance. They heard some coughing and were surprised to see Chas back so early. In fact he had been away for over an hour, but to the engrossed pair it seemed like minutes. They retired to his office for further questions over another pot of tea, and suddenly they both felt very weary.

Chas rounded up the visit saying, ‘I wish you all the very best, and success for Operation Lavivrus.’

On the way back to Hereford Peter said to Tony, ‘Do you know what I’ll always remember about this visit?’ Tony shrugged in answer, and Pete said, ‘The curtains in Chas’s office.’