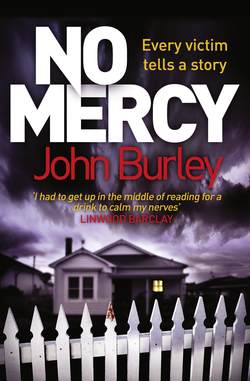

Читать книгу No Mercy - John Burley - Страница 13

Chapter 5

ОглавлениеNat had been right about one thing. The press was going to have a field day with this one – a regular three-ring circus. Ben could make out the congregation near the front entrance to the Coroner’s Office from a quarter mile away. The usually dimly illuminated front steps of the CO were now bathed in bright artificial light as at least three different television crews jostled for position. Two patrol cars were parked just across the street, and a third one blocked the left lane of traffic to allow room for the news crews to set up their equipment without running the risk of being plowed over by a distracted motorist. Ben quickly decided that there was no way he’d attempt to enter through the CO’s front entrance; instead, he turned left on Broadway and right on Oregon Avenue, hoping to sneak in through the building’s rear delivery access.

He parked the car on Oregon and hopped out. Shielding himself from the downpour with his jacket as much as possible, he trotted the half block through the gathering puddles toward Brady Circle. The rear of the CO stood mostly in darkness. The parking lot behind the building was vacant except for two vehicles. One was the coroner’s van that Nat had used to transport the body. Beside it, a second van, which Ben didn’t recognize, sat idling, a white plume of exhaust rising up in a dissipating cloud from its tailpipe. As he approached, the side door of the vehicle slid open and two men stepped out, making their way toward him across the parking lot.

‘Dr Stevenson?’ one of them asked from the darkness.

‘Yes?’ he replied cautiously.

Ben was suddenly bathed in the bright light of a television camera.

‘Dr Stevenson, is it true the victim was stabbed forty-seven times? Has a positive identification been made yet?’ asked the reporter, thrusting a microphone in his face.

‘I haven’t examined the victim yet. That’s what I’m here to do now.’

The man with the microphone didn’t seem to appreciate the finer points of Ben’s statement, for he continued to fire off questions one after the other. ‘Is the victim a resident of the town, Dr Stevenson? Someone you happen to know? Was there any weapon found at the scene?’

‘How am I supposed to know that? You should be talking to the police.’ Ben fumbled for the keys in his pocket.

‘What was the last homicide of this nature that you investigated, Doctor? Have you spoken with the County Coroner’s Office or the state police?’

‘I haven’t spoken to anyone except my assistant.’ Ben turned the key in the dead bolt and swung the door open just wide enough to step inside. ‘Now if you’ll excuse me …’

‘Dr Stevenson, you have a son of your own that attends Indian Creek High School. How did he take the news of a murder only a few blocks away from the school?’

‘He seems to be handling it much better than you are,’ Ben replied, then closed the door against the deluge of questions from the overzealous reporter. He flipped on the light in the back hallway. It was blessedly quiet inside the building. He could hear the faint sounds of Nat moving around in the autopsy room beyond the door at the end of the hall. His assistant had the habit of humming softly to himself as he went about the task of laying out the equipment and preparing the body for examination. It was mildly endearing, although Ben could never recognize the melodies, which belonged to a musical generation that was not his own. Ben hung up his jacket on the coat rack to his left and proceeded down the hallway.

‘Hi, Nat,’ he said as he entered the room.

‘What’s up?’ Nat responded cheerfully. ‘Did you get hit by the reporter brigade on your way in?’

‘Of course,’ Ben replied. ‘I thought that I might outsmart them by coming in the back way, but they had their sentries waiting for me.’

‘No doubt, no doubt. They were on me like flies on sh –, like flies at a picnic, you know, as soon as I pulled the wagon into the back parkin’ lot. “Tell us this! Tell us that!” Those guys are pretty damn …’

‘Importunate? Unremitting?’ Ben offered.

‘Pretty damn annoying, if you ask me. Hell, I don’ know the answers to any of those questions. Might as well be askin’ me who’s gonna win the Kentucky Derby. And if I did know, I wouldn’t be tellin’ ’em nothin’ anyway. Just like you said, Dr S: “No muthafuckin’ comment!” Right?’

‘I think that was actually you who said that.’ Ben glanced at the shape on the examination table, still zipped up inside of the black cadaver bag. ‘How are we doing?’

‘I just got back about ten minutes ago. Fog’s gettin’ thick out there, and the wagon’s front windshield defroster ain’t workin’ so hot. Rainy days – and rainy nights especially – you’ve got to drive slow, or else you might find yourself joinin’ the gentleman in back, if you catch my meaning.’

His assistant continued to move about the room as he spoke, laying out instruments and checking connections. He was a study in controlled chaos: his light blond hair eternally tussled as if he had just recently climbed out of bed, the tail of his shirt tucked into his pants in some places but left free to fend for itself in others, one shoelace frequently loose and on the brink of coming untied – and yet within the autopsy room he was highly organized and efficient, as if the manner with which he conducted his personal life did not apply here.

‘I’ll ask Jim Ducket to take a look at it,’ Ben told him. ‘If you’re having trouble with the wagon, maybe we can get a replacement from the county until we get it fixed.’

‘Aw, the wagon ain’t no trouble. Just needs a little kick in the nuts every now and then. If you want Jimmy Ducket to take a look at anything, have him check out the radio. Hell, half the stations were set to classic rock when I climbed in it tonight. I take one five-day vacation and the whole place has gone to hell.’

Ben smiled. Nat had gone on a ski trip to Utah with his father last week, and Ben had been left making the pickups himself, just as he’d done before his assistant had come on board with him full-time several years ago. A few radio station adjustments had been the first order of business on his way out to pick up Kendra Fields, who’d died in her home last week of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. When Ben arrived at the residence, Kendra’s husband, John, had been waiting for him at the front door. ‘Guess she’s gone and done it this time, Doc,’ the old man had said matter-of-factly. John was eighty-nine and belonged to the congregation at Ben’s church. Kendra had been three years his elder, and during the course of her life had survived two heart attacks, a serious stroke, breast cancer and a small plane crash. All things considered, it was time for her to pack up and head for home. Ben had chatted with John for half an hour. Then he’d loaded Kendra’s body into the back of the wagon and had treated her to some Creedence Clearwater Revival on the short ride back to the CO, cranking the volume up enough to turn people’s heads as he drove past. Hell, on top of everything else, Kendra Fields had also been a touch deaf during her final ten years on this earth.

‘Well, that’s what you get when you skip town and leave us old farts to drive the wagon,’ he advised his young colleague.

‘Yeah? Well, never again,’ Nat assured him. ‘Next time I leave town I’m takin’ the keys to the wagon with me. You can use that old beat-up jalopy of yours to pick up folks if you have to. Stuff ’em in the trunk, for all I care.’

Ben crossed the room and pulled a plastic apron down from the hook on the wall where it hung. He donned an eye shield, head cap, shoe covers and latex gloves, and approached the awaiting corpse. He was glad that Nat was here to assist him and to keep him company with his incessant, irreverent chatter. Ben filled his lungs with a deep breath, and let it out slowly through his nose. With his right hand he grasped the bag’s zipper and pulled it down.

The first thing he noticed was that the subject was young, perhaps fourteen or fifteen years old. His skin was smooth and slightly freckled around the face. His eyes, still open, were dark brown, interlaced with a touch of mahogany. His hair was also brown, but several shades lighter than his eyes. A long lock hung partially across his forehead, tapering to a point and ending just shy of his left cheek, above the first of several obvious facial wounds. The flesh in this area had been torn completely away, leaving a jagged vacancy.

‘Jeeeesus,’ Nat commented. ‘That’s one hell of a chunk gone from his face, Dr S. What do you think he hit him with?’

Ben studied the gaping wound for a moment, peering closely at its serrated edges. ‘That’s a bite wound,’ he said quietly. ‘Hand me the camera.’

Nat walked across the room, opened a cabinet, and returned with the lab’s digital camera. ‘Bit him,’ he repeated softly to himself, mulling it over. ‘Now, that’s messed up.’

Ben snapped off several pictures of the facial wound. ‘In multiple places.’ He pointed to the right side of the boy’s lower neck. ‘See here?’

A second, wider piece of flesh was missing at the spot Ben was indicating. The boy was still dressed in the clothes he had died in, and the collar of his black, loosely fitting T-shirt was torn in this area and caked with dried blood. Ben inspected the wound carefully, using forceps to pull back a flap of skin that hung limply across the opening, partially obscuring it. A voice-activated recorder hung around Ben’s neck, and he spoke into it in a neutral, practiced tone as he worked: ‘Dr Ben Stevenson; March 29th, 2013; case number—’ He looked at the large dry erase board hanging on the wall. ‘Case number 127: John Doe. Received directly from the crime scene, custody transferred from Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department.’ He took a breath. ‘Subject is a Caucasian male, approximately fourteen years of age, dressed in a T-shirt and blue jeans. Inspection of the face and cranium demonstrates a 3.6-by-4.1-centimeter soft tissue avulsion injury beginning superficial to the left zygomatic arch and extending inferiorly to involve the lateral portion of the orbicularis oris. Avulsions of the zygomaticus major and minor are noted, with wound depth extending through the masseteric fascia.’ He lifted the boy’s chin slightly with one gloved finger, using a thin metal instrument to probe a penetrating wound noted there. ‘Inspection of the submental region demonstrates a puncture wound measuring 0.75 by 0.9 centimeters, which extends through the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles, continuing superiorly and dorsally through the body of the tongue, soft palate and nasopharynx. There are seven – correction, eight – similar puncture wounds to the cranium that extend through the scalp, underlying musculature and galea aponeurotica. Two of the eight wounds penetrate the skull and enter the cranial vault. A second avulsion injury is noted at the right inferolateral aspect of the neck 5.3 centimeters medial to the acromioclavicular junction and involving the inferior platysma, lateral trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles, as well as the right external jugular vein.’

This part of the examination – the initial inspection and description of the body – was the portion of the necropsy Ben always found most interesting. Every corpse, he found, had a tale to tell, and the details of one’s life were often prominently revealed by the compilation of physical marks collected along the way, like scrapes and gouges on the underside of a boat. Prior scars (both surgical and traumatic), tattoos, track marks from a lifetime of IV drug abuse, burns, calluses, fat and muscle mass distribution, exaggerated spinal curvature from decades of stooped physical labor, tan lines, nicotine-stained fingertips, chewed fingernails and even the state of a person’s teeth often spoke volumes about the course of their life. In Ben’s opinion, these were not only the most interesting details of the examination, but also the most aesthetically beautiful – strange words to describe the physical blemishes of a corpse, perhaps, but he was a pathologist, after all. These marks and imperfections represented more than simple anatomy. They had been born from action, behavior and life experiences, and were therefore the most human, the most in touch with the life they had left behind.

In the case of traumatic deaths, however, it was different. One’s eye is inexorably drawn to the fatal injury – that which has extinguished the flame of life so abruptly. Especially in the case of young people, the autopsy ceases to be about discovering the marks left behind from a life richly experienced, and rather is about bearing witness to the end of a life barely begun. Such was the case here, as Ben moved from one disfiguring injury to the other, each one denoting a blatant disrespect for the life of this young man, and for human life in general. It was a tragedy to behold. He wanted simply to stop, to cover the form in front of him with cloth, to save it from this last final disgrace. Instead, he continued, using practiced and precise descriptive terminology like a shield to defend himself from what was real.

‘Inspection of the thorax demonstrates puncture wounds to the right fourth and sixth intercostal spaces anteriorly, and to the right fifth, seventh and eighth intercostal spaces along the midaxillary line. There is a 4.1-by-3.8-centimeter serrated avulsion of the left areola and underlying pectoralis muscle, similar in appearance to those of the face and neck, described above. There is a displaced fracture of the xiphoid process. Inspection of the abdomen demonstrates a 0.8-by-0.9-centimeter puncture wound to the right upper quadrant, and two similar puncture wounds to the right flank. There is a 35-centimeter diagonal incision extending from the right upper quadrant of the abdomen to the suprapubic region, penetrating the rectus abdominus and peritoneal fascia. There is evisceration of the small bowel. The genitalia are … missing.’

He paused for a moment, looking up at Nat, who was positioned across the table on the other side of the body. Most of the color had run out of his round, boyish face as he stood bolt upright and unmoving, eyes transfixed upon the body. Ben was suddenly embarrassed. He should’ve had enough sense to send Nat home as soon as he’d unzipped the bag. This was not something a twenty-two-year-old needed to watch, regardless of his chosen occupation. When Karen Banks had agreed to allow Nat to volunteer at the CO, she had done so with an implicit understanding that Ben would watch out for her son’s physical and psychological welfare, and he regarded the trust and deference Nat’s parents had extended to him seriously. During his time at the CO, Nat had taken part in scores of autopsies, in cases ranging from the ravages of metastatic cancer, to self-inflicted gunshot wounds, to the death of young adults involved in motor vehicle accidents. He had even assisted during pediatric autopsies – cases of SIDS and child abuse. The boy was no novice at witnessing some of the trauma and unpleasantness that could descend upon the human body. But this … well, this was a different matter altogether.

‘Listen, Nat. Why don’t you let me finish up here,’ he said. ‘It’s late, and I’m going to need you in the office early tomorrow to help Tanya man the phones. From the look of Brady Circle out there, I don’t think the press is going to give up that easily, and I imagine that Sam Garston from the Sheriff’s Department will be stopping by bright and early looking for the coroner’s report. The rest of this stuff I can just take care of by—’

‘Umm … Dr S?’

‘What is it, Nat?’

‘This case here is the most interesting, most important thing we’ve had come through these doors over the six years I’ve been workin’ here.’

‘I know. It’s pretty—’

‘And if you think … if you think I’m goin’ home in the middle of the autopsy just because some nutjob lopped off the guy’s wiener and chucked it into the woods, well … you can forget it.’

‘I wasn’t trying to—’

‘You wanna weigh all them organs by yourself, type the report and spend another forty minutes cleanin’ up afterward?’

‘I think I can handle—’

‘How many hours you wanna be here tonight anyway, Dr S?’

‘It’s not about—’

‘No way. Discussion over. I’m stayin’. Or … or you can find yourself another assistant.’

Nat stood across the table, arms crossed, glaring defiantly back at Ben. The two considered each other in silence, neither flinching, for perhaps twenty seconds. Apparently, Ben realized, his assistant was quite serious. He considered his short list of options: send Nat home and risk losing him as an assistant, or allow him to stay, thereby rendering himself at least partially responsible for the possible long-term effects the experience could have on the boy’s psychological well-being.

‘How do you know?’ Ben asked. He was buying time while he tried to make up his mind.

‘How do I know what?’

‘How do you know the assailant chucked his wiener, as you like to put it, into the woods?’

‘Oh. Cops found it at the scene. Fifty yards away from the body. Police canine actually tracked it down. It’s in a Ziploc bag taped to his right ankle.’

‘I … see,’ Ben said.

The two men stood there for a while longer, neither speaking, as they surveyed the mutilated body.

‘Well, what’s it gonna be?’ Nat challenged, impatient for a decision.

‘I don’t know,’ Ben sighed, tapping his fingers on the table. ‘I’m trying to decide whether I want to be responsible for further corrupting your already quite tenuous psychological stability.’

‘Too late, Dr S! I hang out in a Coroner’s Office. My psychological stability is already all blown to hell. Now gimme that scalpel. I’m gonna slice-an’-dice this turkey like a Thanksgiving dinner.’

Ben looked at him incredulously, shaking his head. ‘That’s so inappropriate I don’t even know where to begin.’

‘How ‘bout you begin by pluggin’ in that Stryker saw for me, will ya?’

‘Riiigghht.’

‘Okay. I’ll do it myself.’ Nat bent over and plugged the instrument’s umbilical cord into the outlet on the floor. ‘You want the chest opened, right? The usual?’

Ben said nothing.

‘Great.’ Nat nodded, as if he’d been given the green light to proceed. ‘Now step back, boss. I don’t wanna get shrapnel on your pretty white apron there. You jus’ leave this part to me.’

He picked up the bone saw and went to work.