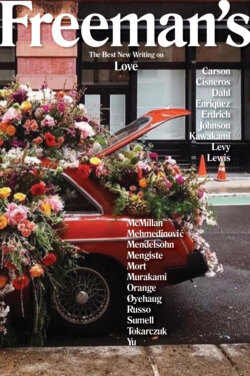

Читать книгу Freeman's: Love - John Freeman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

John Freeman

The first time I sent a love letter, I misspelled “love.”

Or nearly did.

This would have been around 1979. I was lacing up my shoes to sprint over to my classmate Betsy’s house when my mother found me. Where are you going? I hadn’t yet learned to feel ashamed of myself, so I told her.

I’m going to put a love letter in her mailbox.

Can I see?

My mother spoke that way. Not, let me see; or hand it here. But, can I see? I showed her the love letter.

Oh honey, you might want to change this. You spell “love” like this.

She wrote the word down carefully in her perfect looping penmanship. Seeing the way she put down words, like each one was loved, would make me cry years later, after she’d died, at the sight of things she’d written.

I looked at the word. It didn’t look more like love now that she’d written it. Rather, it was like she had told me a leaf was bark, and bark a leaf. Did it matter? Who made such arbitrary decisions? Sometimes you just loev someone.

I corrected the word, laced my shoes, and ran off—a reverse bank robbery. Leaving something behind, not taking it.

I never heard back—or at least not directly. Perhaps this is why so many five-year-olds’ love letters are structured like multiple-choice questions. Maybe I hadn’t yet learned that love was something you waited for to return. Like a boomerang. After all, I lived then in love’s constant, endless return. I loved my father and sometimes he would walk by and pat my head, like I was a dog. I liked that. My older brother often crawled into my bed at night when he was scared and the warmth of my body made it easier for him to sleep. I liked that too.

As a child I recall feeling so full of love it was natural to constantly give it away. To old people. Strangers. The marching band. They walked right by my house, throwing batons and people in the air. We got pets to have something around us to love, even if they ran away, like all our gerbils. We developed crushes the way rivers grow tributaries. Everywhere I went, love was operating in some constant, unquestionable fashion—like gravity.

Childhood, when it’s safe, teaches us to love. I was lucky, so lucky, to have had the kind of childhood I was given. It would be years before I learned that love might endanger me; that love could break me; that I could love someone and they wouldn’t love me back. Or maybe they’d use that love against me. When I was lacing up my shoes, I was sending out love into a world that had always, only, returned my love in some fashion or other—an attitude I see in children now and hold my breath.

One fundamental difference between us and children is how we wear these lessons, which accumulate with age. Whether it makes us wary, or skeptical, or hopeful, or estranged, or physically tense. How we move our bodies is shaped by how love has entered our lives. Where the stress fell, where its tenderness turned a receipt of love into a habit of being. Where its departure left scars. Our body becomes the way we hold these contradictions: love’s pleasures and its pain.

Still, no matter how small the weight, or how odd the contradiction, love is too much for any one body to hold, and so we tell stories about love, write poems to it, tell memoirs of its survival. Love is the biggest and most complex emotion, the most powerful, it cannot be held in the palm of our hand—even when it’s a child’s hand resting there. So we put it into the only container made stronger by such contradictions—a story.

This collection celebrates writing on love, and it also makes a case for the love story to be about more than romantic love. What if love could be felt in more directions than between one human (or two) and another? Louise Erdrich writes a poem from the perspective of a stone to the earth. What knows more about longevity than a stone?

Time alters so much here in its wind tunnel. In Semezdin Mehmedinovic´’s profoundly moving essay, he describes how, caring for his wife in the wake of a stroke, he has to repair time for both of them. Soldering here (Washington, D.C.) with there (Sarajevo); her body (now broken) with her bodies (all the selves he knew through the years), he sings a psalm to the power of love to hold so much together. He plays games to trick her memory back to life, and thus restores to them their great treasure—how love held them, these two people, together, for so many years.

Of course time presents challenges to lovers united in relative health, too. How to love someone when they cannot go where you go, each night, away from the land of Nod? This is Daniel Mendelsohn’s great dilemma, as an insomniac. How do you make a spouse know what you feel, Niels Fredrik Dahl’s poem wonders, when your words, repeated over the years, have worn a path to the ear? How do you wear someone else’s past, if their troubles—Maaza Mengiste thinks, entering a world with her elder’s name—are not your own? How do you show it love? What do you owe it? In her brief piece, An Yu recalls encountering an old woman who made shoes one night in Shanghai—with her flat hard accent so reminiscent of Yu’s own family, she draws love forth from Yu, unthinkingly, in the night.

Familiarity cuts so many ways in love. It can give you the safety to play a game, as Robin Coste Lewis describes her parents playing, in the sexy poem, “High Fidelity.” Or that familiarity can lead to a wizened, shared sense of entanglement. In her hilarious poem, Sandra Cisneros reminds of how love can feel like a dance we know the steps to, and cannot resist—even when we know someone might end up on the floor. In Richard Russo’s short story, a couple conducting an illicit affair confronts the end of their time together—something which they knew loomed on the horizon from the very beginning.

How to tell a story when you know the end? How to reengineer that story so it reflects the ways a tale sometimes unfolds with one party more entrapped than entangled? Gunnhild Øyehaug’s story performs this feat by slipping her yarn—of an older man and a younger woman—through several trapdoors until it’s back in the hands of the woman who lived the tale, not the man who prompted it. Valzhyna Mort’s poem elegantly skewers the question of whose biography matters, the speaker’s, which is lived, or the poet’s, whose work he was desperate to hand her. Anne Carson, who has spent a lifetime in academia, describes the kinds of interactions that often undergird the power dynamics therein, driven not only by age and intellect, but also by an accompanying male entitlement.

It’s a hard time to believe in love. So many spectacles of its opposite are on display. It is tempting to abandon real love and simply believe in its fantasy, or only in love for the absolutely pure and cute. Dogs, cats, pets of the earth. Matt Sumell has arrived at a version of this, all while holding his integrity in hand like an odd hat. In his heartbreaking piece he describes how he has made a moral choice to love what no one wants to love: the dogs people throw away.

To write love today demands we engage such depths, where anger and shame meet longing and comfort, lest we make a fantasy of love. Hindsight helps, too. In her wondrously honest piece about an ill-advised affair she had in her youth in Paris, Mariana Enriquez marvels at the risks her younger self took for the dream of a French romance. Maybe it’s not just in youth that we do this; perhaps we’re all just making it up as we go along, pulling from a set of impulses that we discover, as Tommy Orange does, writing about learning to love his family, are so full of danger that to contemplate them for too long could mean giving up on love entirely.

What a joy it is, then, when one finds a love about which one can say—this I know. It’s as magical as, say, swimming in the snow, as Deborah Levy puts it; or as strange as a one-night stand, as Haruki Murakami’s characters experience it. Luminescent, strange, almost holy, but also: how to decide if it is enough? How much light do we need an encounter to contain to be called love? Can a night ventured be called love? Is there a duration required? Must it last a day, a week, a year?

How desperately we need each other, to ask these questions. As siblings, fellow travelers, friends. In an excerpt of Mieko Kawakami’s novel in progress, “Heaven with a Capital H,” two pals go to a museum, and love becomes the way they reinforce each other’s moods as they try to define what it is that brings them joy. Love is how they allow the other to even ask for it. Similarly, more darkly, in Daisy Johnson’s story one sister—who is well—makes a creature of mud and stone for the other, who is dying. The narrator realizes the competition for attention with her sister is running out, that for the rest of time she will be left with a lack. That it is time for her to simply provide the unasked for gift of happiness.

Stories, poems, literature allow us to see love’s evolution. Even if we are born to vast, encompassing love, we can learn to appreciate it by seeing how it changes. Whether our parents exist for us or not; whether they stay together or not; whether our own lovers return our care, or not. Whether they survive an illness—or, in the case of Olga Tokarczuk’s devastating story—not. These questions almost always are beyond our control. What a vast network of exposure this reveals; we are all, constantly, facing the ravishment love entails. In his series of poems, “swan,” Andrew McMillan shows how one way to live in a world of such precariousness is to take over one’s own evolution. To say here, take me like this; or this; or this. Tell me how to be. Watch me evolve for you.

And anyone who has ever waited for the answer to a message sent across town will hold their breath.