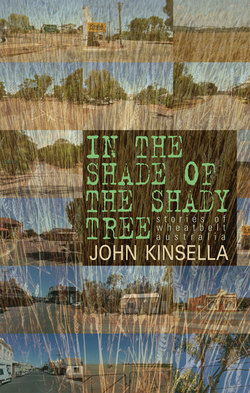

Читать книгу In the Shade of the Shady Tree - John Kinsella - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеpreface

Last night a storm hit this drought-ravaged place without warning. It was a brutal assault. We kept our roof, but neighbors lost theirs. There are a number of large York gums down—snapped off low on their trunks. Inside the trunks, the soil welded by excreta and saliva of termites crumbles out. So many of the trees here are hollowed by termites. Echidnas scrape at the base of the trees for termites—we often see their telltale diggings, but rarely the nocturnal echidnas themselves.

We received thirty-two millimeters of rain last night, the most in a single downfall for five years. It’s a reprieve for a lot of the life on this block and the surrounding area—drought has killed many trees, and the effect on wildlife has become evident. It has been diminishing, not only from lack of water, but from increasing pressure of human occupation.

On lands that are traditionally Ballardong Nyungar, clearing and poisoning and other abuses of place have taken their toll, and continue to do so. Just over the hill begin the vast wheat and sheep farms of the Victoria Plains district, part of the Western Australian wheatbelt. Devastation caused by this monocultural farming is seen in ever-increasing land salinity, and in changing local weather patterns, due not only to larger global processes but also to localized land-clearing.

I first entered the wheatbelt when I was a few weeks old. My uncle and aunt’s farm, Wheatlands, was a beacon of my childhood. As I grew up, I spent many weekends and holidays at Wheatlands. The grain silos, heart of the many towns that dot the wheatbelt’s hundred and fifty thousand square kilometers, are fed by farms like Wheatlands, often handed down through generations. Nowadays, they are breaking up as eldest sons no longer inherit the lot. Divided up between the children, the farms are often sold on to large companies: corporate agriculture.

The history of the wheatbelt is multicultural, though the divisions of spoils are lopsided. Anglo-Celtic colonizers (“settler”-migrants) dispossessed the indigenous peoples in the nineteenth century and exacted their labor. Colonists later relied on convicts (petitioning for their presence in the colony!), then migrants who came with the 1890s gold rush, and still later the great migrations prompted by conflict in twentieth-century Europe: Italians, Yugoslavs, Greeks, Poles, and many others were paid a pittance to clear the bush for grain growing. Some of these people eventually established their own farms and their own dynasties. Others failed. For every success in the wheatbelt there is a failure. It is harsh in many ways.

My poetics and sensibilities formed not only in the paddocks and remnant bushland, but also on the vast salt scalds where very little grew or even lived. But there was life there if you looked; and I did look. Though they were the result of European overfarming, and truly a blight on the land, I discovered, in the gullies and scalds of “the salt,” mysteries, wonders and beauties that have fascinated me all my life. Complex formations of salt crystals, the “puff and bubble” of salt tissue over mud, the harsh reflector beds of white in summers that reach the high 40s centigrade. My entire poetic output has been grounded in the contradictions of the terror and beauty of salinity.

Yet it is not only poetry I have written through my life: there are also stories. The poetry has been about place in a very empirical way, concerned with damage and its implications. But in my stories I am more concerned with glimpses of the people who live in the wheatbelt. Whether I approve of their activities or not is irrelevant. What is at issue is how they interact with the place, and how they make that place what it is. I am interested in the weirdness that comes from the ordinary, the extraordinary from the matter-of-fact. The behavior of people seems more odd to me than, say, supernatural belief. I ask how secrecy is part of everyone’s lives, and how disturbance goes hand-in-hand with the predictable. A good deed can mask ill intent; a bad deed can result from well-meaning acts. There are rarely neat resolutions, and other than death, few absolute conclusions. Even death leaves loose threads, many loose threads.

Underlying all these glimpses is the knowledge and acknowledgment that I am writing a land stolen from indigenous people; that in truth it is still their land, if it’s anyone’s. I have never believed in property per se, nor in “ownership.” I see my role in this place as one of “carer,” one who has a responsibility to observe, discuss, and even protect.

But these stories aim to do something else: they are a jigsaw puzzle that offers the reader, I hope, a way of seeing how small fragments of the place work, or don’t work. Some have fable-like morals, others are fantastical, but many are just “insights” into an aspect of being here. I am interested in the glimpse into character, and how that character is affected by “place.” No one’s entire story can really be told. Yet many stories or glimpses added together, collated on a journey, might give us a broader picture of the so-called human condition.

In the vein of one of my favorite Australian story writers, Henry Lawson, I really see them as yarns: stories told for the moment, out of experience more than “art.” But they are informed by an artfulness, if not an art. One of my favorite volumes of American stories is Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, which most would know is artifice on the level of story but “truthful” in the insights it gives into living in a small town somewhere in Midwest America, if not in the eponymous town itself. I lived in Ohio with my family for a number of years. Our son was born there. I see it as a home. We went looking at the real Winesburg knowing it wasn’t the Winesburg constructed by Anderson. And that was okay—it interested us to see how the stories had affected the town, and of course, they had.

When we write place, we necessarily contribute to a view of what that place is—even such a vast place as the Western Australian wheatbelt with its many, many towns, varying in size from the seven thousand population of a regional center like Northam to the handful of residents in places like Jennacubbine. Our contribution to the view of the place is always disproportionate, even if only read by a single reader. Because the life of that place is only ever a glimpse, is selective, and often largely a construct. And that’s true of this book as well. The stories herein follow a roadmap from the northernmost point of the wheatbelt, up near Northampton, down to the Great Southern, where the wheatbelt becomes something else. Each town passed through is given a tale that might or might not capture something “real” about that town or its district.

What I hope the book captures is something about people, and the way people make lives of place and alter that place in doing so. What happens in one story in one town or district might just as easily happen three hundred kilometers away in another part of the wheatbelt. But the stories did come out of those places, so immediately a sense of belonging or maybe alienation locates itself quite specifically on the compass. I find these apparent contradictions fascinating.

I have lived with my family on and off in the wheatbelt for many years. I am quite reclusive, but when I emerge I look and listen closely. I am part of the district, especially around York, where I have lifelong family connections and lived for many years; Northam, the main center of the same region; and the hills north of Toodyay, which we now call “home.” Each of these locales has had disasters and incidents that have brought communities close together and also divided them. Then there are those figures who always remain outside any community. They also interest me. As does how “isolated” farming places (I have always been interested in the particulars of farming, whether I agree with aspects of them or not) connect or distance themselves from the world at large. The prejudices, bigotries, and scepticisms need to be read and “glimpsed,” as much as the affirmations.

I went to high school in the midwest seaside town of Geraldton (now a small city of thirty-two thousand), about 420 kilometers north of the state capital, Perth. Geraldton is a fishing, farming, and mining town. The huge wheat farms that edge the coast are carved out of “sandplain” and are worked using vast amounts of superphosphate and chemical sprays. As a kid, I spent time with my father on a thirty-thousand-acre farm near Mullewa, east of Geraldton. There were tractors with wheels twice my height (machinery at once disturbs and fascinates me). I was traumatized by the clear evidence that the Yamatji people of the region were cut off from their traditional lands, and by the suffering this brought. I had long been familiar with gun culture and saw on a large scale what hunting was all about. By the time I was in my very early twenties, I had become a dedicated vegan. I had the experience to make a clear-cut choice. I did plenty of damage to birds, fish, and animals as a child and a teenager.

When I was twenty, I went away to Mingenew in the northern wheatbelt to work on the wheatbins. Enormous receiving silos. I was a protein sampler. I used the money earned to travel through Europe. I went back the next season and came into conflict with an ex–South African mercenary who was driving a grain truck and held extreme racist views. I resisted and was punished. I witnessed bigoted and aggressive behaviors during that stint that I hope never to witness again. This is always in the back of my mind. But so is positive experience, such as ploughing under the stars on Wheatlands farm, or looking after the farm over summer months—a twenty-one-year-old with responsibility for a large farm is something else. Or again, planting avocado trees with my uncle as he tried to diversify out of monocultural farming, or helping plant trees (they planted tens of thousands) in saline areas to try to reclaim damaged land.

All of these aspects are part of the wheatbelt for me. Giant “food bowl” that it is, its “feeding the world,” as they like to say, has come at a great cost to indigenous people and to the land itself. It has also come at a cost, ironically, to those who colonized, cleared, farmed, and lived there. The suicide rate, especially among males, is phenomenally high, and the sad spectacle of a land dying through salinity and drought goes hand-in-hand with more damage and more misunderstanding of denying the consequences.

In the end, it’s a place of people: their successes and failures, of materiality and spirit. Though the wheatbelt is bound together by the central activity of grain farming, it ranges in geography from coastal plains to semi-arid marginal land, on the edge of the outback, producing very low yields, through to much richer lands (though the soils are still impoverished, there are higher rainfalls) in places such as the Avon Valley, with its ancient river course formed by the Wagyl spirit outside time, and holding the ancient eroded Dyott Range.

To tell more of the place, maybe it’s best just to describe a few towns from the wheatbelt. Following are some of the towns with which I am very familiar, and which in many ways form reference points in my own journey. These are not historical renderings, but impressions formed from living in the regions. In some ways, maybe they are stories in themselves.

York

Earliest inland settlement in Western Australia, founded in 1829. The governor had a residence there, and the police searched for escaped convicts and suppressed the indigenous inhabitants from its police station. The old court building is a tourist site now. Homeland of the Ballardong Nyungar people. I have been in and out of York since I was born—my uncle’s farm, “Wheatlands,” was twenty kilometers northeast. For many years we lived about five kilometers north of town. My mother still lives there. Some call it the “gateway to the wheatbelt.”

As rainfalls have dropped and drought has gripped, an “historic” town such as York has begun to rely increasingly on weekend visits from the city of Perth, a hundred kilometers southwest. York’s early stone buildings, its “colonial history,” and the area’s deeply spiritual significance to the Nyungar people make it a standout in the state.

The town, located on the Avon River, is remarkably beautiful, though the surrounding land has been much damaged by attempts to “train” the river to prevent flooding—that is, dredging it so waterholes, which would once have survived the brutal summers, no longer existed—and devastating salinity caused by overclearing of surrounding lands, as well as clearing of riparian vegetation. In fact, it’s one of the few spots where water stays in the river all year round, even in drought.

Cradled between the small mountain of Walwalinj, or Mount Bakewell as named by explorer Ensign Dale, and Wongborel, known to the settlers as Mount Brown, York is at the crossroads of the Avon Valley. A fiercely independent-minded town, it is home to the deeply religious as well as to the heretical and nonbelieving. Christianity in many denominations is prevalent, and if it isn’t “Bible-fearing,” as some of the more inland wheatbelt towns are, the manners of belief there are always in the background. Anglican gentility informs much of the cultural endeavor of the town, whether it’s an arts festival or baroque music in Holy Trinity, across the swing bridge over the Avon River. But there’s a Catholic church that looks like a small cathedral, and there are halls and meetinghouses of other churches.

Developers eye York with glee; the friction is intense between those who would make a buck and leave and those who see York as a chosen lifestyle place. Bounded on one side by wandoo bushland and by York gum/jam tree woodlands on another, the place suffers more clearing and damage each year. It is conservative, but with a sprinkling of radicals who are generally tolerated because York prides itself on being a cultural place. That’s European-derived culture. But it’s also a center of Nyungar culture, where the strength lies. There is racism and division in the town, but possibly less so than elsewhere.

One of the current greats of Australian Rules football comes from York, and white and black are intensely proud of him. But the town is still subtly controlled by the power of land ownership. The big voices are the big farmers. I wrote a number of these stories in the historic York Post Office building, designed by Temple-Poole in the second half of the nineteenth century, where I had an office within the two-foot-thick stone walls. On the single main street running south to north, I looked out over the day-to-day activities of the town. An incident outside the bottle shop, dogs barking on the back of utes, as Australians call pickups.

Northam

Main town of the central wheatbelt and Avon Valley. A regional center of some seven thousand people, providing the only senior high school for vast distances. It services the broader farming community of the region. The railway here has been important over the years, and one of the largest inland grain-receival points sits on the outskirts of town. The wide paddocks that spread throughout the region carry crops of wheat, barley, oats, canola, and other seeds/grains. Wheat is the mainstay. It is railed and trucked from the bins to the ports (primarily Fremantle/Kwinana) for export. An historic and still functioning flour mill sits on the river at the southeastern end of town. Shearing is also a major industry, with shearing teams buying their gear, drinking, and often living there when not out working the sheds.

Northam has a regional hospital, the main regional courts, and a large police station. It is a violent town, with a high crime rate and often literally blood on the streets, especially outside the hotels. It used to have a small cinema complex, but that closed down because of late-night violence. It has an active and high-quality amateur dramatic company that uses a theater based in an old church building—farce and comedy are their mainstay, which draws locals. The high school puts on an annual play there—our daughter featured in the production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. There is also a regional art gallery. There are four large old-style drinking hotels, and a lengthy main street with shops, plus a small arcade.

Sports are a big part of the town’s life, dominated by Australian Rules football, netball, and cricket. This is true of most wheatbelt towns, but there is much more infrastructure in Northam. Our daughter used to bus a seventy-kilometer round trip to school. An historic town, with the legendary, introduced white swans that have been a feature of European colonization here for over a hundred years. It is the starting point of the famed (and environmentally destructive) Avon Descent, the longest whitewater boat race in the southern hemisphere; that’s in years when there’s any water to race along.

After the Second World War, the town housed many European migrants. Their tales of hardship adjusting to the heat and flies and Spartan conditions are told in a commemorative display at the tourist center. Ironically, given this, Northam has a racist history. Many of the Ballardong Nyungar families of the region were broken up, and the place is notorious for the removal from their Nyungar families of children who were considered to have “white blood.” These children were part of the horrendous reality of the Stolen Generations, the damage of which resounds to this day. Many of the children ended up at the Moore River Settlement, several days’ walk away.

Recently, Northam’s racism and bigotry have run out of control with the announcement of a refugee holding center, for Afghan males, to be established at the old army base. You cannot walk the streets without being confronted by signs screaming “Parasites,” or demonstrations with people wearing T-shirts that declare, “Send back their boats” or “Bomb their boats.” There is a more liberal side to the town (though small in number), who call for humanity and respect for all peoples.

But Northam is a divided town; its indigenous inhabitants experience racism on a daily basis. I was one of those who refused to shop at a major supermarket until charges were dropped against one Nyungar boy (and he was clearly labeled “black” as a pejorative in the media) who was threatened with serious theft charges for possessing an unpaid-for chocolate frog (given to him by a cousin).

On the positive side, there is a firm sense of identity in the black community, with two of the town’s primary schools having 40 percent or more indigenous pupils and significant cultural programmes. The Wheatbelt Aboriginal Corporation is also based there, and there are strong bonds across the various communities outside the racist elements.

Northam is a strongly Christian town (Irish Catholics have been an historically dominant group, along with Anglicans; Baptists and other Protestant denominations now have a strong presence), with deeply conservative views on race, sexuality, and ethnicity. It is also the arts center of the region. The banks and government offices are there, and people from a hundred kilometers or more away do their big shopping and essential business there.

Toodyay

Another early inland town, originally called Newcastle, and at first built on a flood area of the Avon River, despite warnings from Nyungar people that the settlers would be washed out in winter. The town was moved, and the name later changed to avoid clashing with one of the same name in the then colony of New South Wales.

“Toodyay” is derived from a Ballardong Nyungar word meaning “place of plenty.” The area around Toodyay remains rich in native bush and wildlife. There are wandoo, marri, and jarrah woodlands, and York and jam tree environments, such as on our own place. We live about fifteen kilometers north of the town, on a bush block that sees many kangaroos pass by on any given day; that has bobtails and western black monitors, mulga snakes and gwarders, and a wide range of birds, including twenty-eight parrots, red-capped robins, eagles, and tawny frogmouths. There’s an echidna on the block—I see its scratchings daily but have yet to come across it. Our place is strewn with granite and “Toodyay stone,” and there are large granite boulders at the top of the block. The soils around the shire vary from infertile sand to a richer red loam (still low in nutrients).

It’s a tough area—shearers (my brother, further north, is a shearer), farm laborers, bikers, fly-in fly-out miners (who fly north for two weeks on at the interior mines, and back for two weeks off), hobby farms and large spreads mixed together. Jack Daniels and beer are the drinks of choice, and the rock band AC/DC rules. Every year there is a jazz festival in the main street of town, and also the Moondyne Festival, named after a bushranger and escape artist who hid in the hills around the town for many years. Toodyay residents often see themselves as outlaws, and indeed some are. It’s a place of bushy beards and raven-haired women with tats. Alternative lifestylers (Orange People, Wiccans, hermits) live alongside horse breeders, middle-class wine imbibers, and weekend farmers traveling up from the city.

Toodyay is at the edge of the Darling Range, and the Avon River cuts through a range of smaller valleys and hills. It is considered picturesque and is much visited, but in many ways it is a hard-living and violent town. Ferociously hot during summer, it is a high fire-risk area because of the large amount of bush still nestled among the hills. Late in 2009, thousands of acres were devastated by fire, with the loss of thirty-nine houses, many sheds, and many animals. There were no human deaths, though a life was lost in a bushfire here two years before.

Mullewa

Another old inland town, but in the Murchison area six or more hours’ drive north of the capital, Perth. Intensely hot and dry. Home of the Yamatji people, also an area rich in spiritual significance. A place of intense racism on the part of the whites living there. The town is deeply divided and violence is frequent within and between communities.

Mullewa is surrounded by, and services, massive farms. During the seventies my father managed a thirty-thousand-acre spread there, owned by a notorious Perth (and international) millionaire. It is a gun culture out there. In this relatively low rainfall area, the huge sandplain farms rely on large acreages to yield enough to make farming profitable. It’s also a large sheep running area. My brother shears there year-in year-out, being based in the region. He and I went to high school in the regional center, Geraldton, positioned on the coast and about seventy kilometers from Mullewa.

When the paddocks aren’t sand, they are a red dirt almost the color of blood. The vegetation is low and scrubby, with patches of taller trees along the waterways and places where more moisture accumulates. In spring the entire region, at least the uncleared bits and along roadsides, erupts with wildflowers. Tourists drive through at that time of the year, but don’t stay.

The town is still strongly Catholic, and not too far away is Devil’s Creek. Names mean so much, and hide so much. The town has some superb architecture by the Catholic missionary architect Monsignor Hawes, whose churches and associated buildings can be found throughout the northern wheatbelt.

It could be argued that the nonindigenous “side” of the town and the region still perceive themselves as pioneers in many ways. As a kid I got trapped here in a silo with my brother, and met hard, gnarled farm workers who told me about booze, and from whom I learnt that women could piss standing up. Guns were never far away; it was the home of many rooshooters. I started to understand what real horror was. I used to stare into the blank centers of starflowers and wonder. I also used to trap parrots that bit through my fingers.