Читать книгу The Lost Tarot of Nostradamus Ebook - John Matthews - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart One

IN SEARCH OF

THE LOST TAROT

Etant assis, de nuite secrette etude,

Seul, repose sur la selle d’airan,

Flambe exigue, sortant de solitude,

Fait proferer qui n’est a croire vain.

quatrain I:1

While sitting by night in secret study,

Alone, at rest on my brazen stool,

A small flame cancels solitude,

Ensuring my prophecies will not be disbelieved.

The Seer from the South

The history of prophecy is a long one, but one of its most famous practitioners is undoubtedly Michel de Nostredame (1503–1566), better known as Nostradamus. His collections of prophetic writings, originally entitled Centuries (Hundreds), which began to appear in 1555 and continued until 1564, have almost never been out of print, and more than two hundred “translations” and more than twelve thousand commentaries have appeared and been consulted by countless numbers of people since the death of their author.

During this time, the verses have been scanned, interpreted, reinterpreted, and found to contain references to virtually every significant historical event since Nostradamus’ time and well into the future. Thus, it is said that Nostradamus foresaw the coming of Napoleon, the rise of Hitler, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and the destruction of the Twin Towers. The fact that almost no two translations read the same way, or even appear to refer to the same quatrains, might suggest that such interpretations are personal rather than universal. However, there is no doubt that Nostradamus’ writings, when faithfully translated, do suggest some remarkable parallels with certain events—and if only a few of the hundreds of quatrains that make up the complete collection of Centuries appear to be accurate, then we are forced to consider that the rest might be as well.

The life of Nostradamus

As to the man himself, his story is soon told—though it leaves almost as many questions unanswered as do his writings. Born at St Rémy in Provence on December 14, 1503 to parents of Jewish extraction, Michel received an excellent education and quickly showed himself to be of more than usual intelligence. After studying grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy at Avignon, he opted to study medicine, having been inspired by the wandering physician Paracelsus, who was only ten years his senior. His unique abilities and forward-thinking attitude is illustrated by the fact that he told several fellow students that the Earth resembled a great ball and that it revolved each year around the Sun—this at a time when the notion of a heliocentric universe was considered foolish in the extreme, if not heretical, and was not to be proved by the astronomer Galileo (1564–1642) for almost another hundred years.

In the autumn of 1520, Nostradamus’ studies were interrupted by an outbreak of the plague in the area, but rather than return home he set out on the road, putting his medical skills into practice by treating plague victims. He seems to have used largely untried methods, advising not only on treatment but on methods of prevention, hygiene, and diet far ahead of their time.

He remained a peripatetic figure for the next eight years, and to this day his exact route remains uncertain, but it was during this time that Nostradamus decided that medicine was of secondary importance to him. Another skill had begun to show itself—prophecy. Just how Nostradamus discovered his ability to foresee the future remains a mystery, but from 1548 onwards he more or less gave up the practice of medicine in favor of his new art, at which he was soon to prove himself extremely skilful.

In that year he visited Italy, and at some point encountered a young Franciscan named Felix Peretti. The story goes that Nostradamus fell on his knees before the friar and, on being asked why, he answered, “Because I am in the presence of the Holy Father.” Thirty-eight years later, the friar became Pope Sixtus V.

A year before he had set out for Italy, Nostradamus was in the town of Salon. There, he met a lady named Anne Ponsarde, the widow of a wealthy lawyer. They married and moved into a pleasant house on a street now named Rue Nostradamus. After his visit to Italy, Nostradamus added a third story to his house, consisting of what he called his astrologie room. There, on most days, he retired to write the Centuries.

How the man worked

How Nostradamus arrived at his visions remains as much of a mystery as the writings themselves. He left us with a glimpse of his method in the first set of quatrains (note: quatrains are numbered according to their Century, or set, indicated in Roman numerals, and the verse number within it):

Divining rod in hand in the tree’s heart,

He takes water from the wave to root and branch;

A Voice makes my sleeve tremble with fear –

Divine glory, the god sits near.

quatrain I:2

What exactly this means is open to interpretation. However, it seems likely that the seer was using a form of divination in which the viewer stares fixedly into a dish of water until pictures begin to appear. Elsewhere, in the quatrain which heads this part of the book (see page 9), he suggests that he stared into a candle flame until he went into a trance. He also refers to being seated on a “brass tripod,’’ which we may assume was a copy of that used by the ancient Greek sibyl of Cumae, who sat on a similar seat above a crack in the earth from which issued hallucinogenic fumes which caused her to see visions.

In an introduction to one of the editions of the Centuries, Nostradamus stated that he sometimes added pungent oils to the water and that, as he did so, “I emptied my soul, brain, and heart of all care and attained a state of tranquillity and stillness of mind which are prerequisites for predicting by means of the brass tripod.”

Later, when challenged that his gifts may have had a devilish origin, Nostradamus gave what may be the clearest statement of the means by which he entered into a trance, though even here he is enigmatic.

Although the everlasting God alone knows the eternity of light proceeding from himself, I say frankly to all to whom he wishes to reveal his immense magnitude—infinite and unknowable as it is—after long and meditative inspiration, that it is a hidden thing divinely manifested to the prophet by two means: one comes by infusion which clarifies the supernatural light in the one who predicts by the stars, making possible divine revelation; the other comes by means of participation with the divine eternity, by which means the prophet can judge what is given from his (her) own divine spirit through God the Creator and natural intuition.

That Nostradamus was also a skilled astrologer, astronomer, and alchemist is evident—all these skills are referenced in the Centuries—and reflected throughout The Lost Tarot. Indeed, he made it clear that he relied on astronomy a great deal, mentioning it several times in the Preface to the 1555 edition, which he addressed to his son.

Also bear in mind that the events here described have not yet come to pass, and that all is ruled and governed by the power of Almighty God, inspiring us not by Bacchic frenzy nor by enchantments but by astronomical assurances …

The importance of such planetary influences is reflected in The Lost Tarot by the inclusion of astrological reference, established over decades of tarot interpretation.

How the Centuries were received

Nostradamus published the first selection of Centuries in 1555, consisting of 350 quatrains. Despite the fact that they were written in obscure language (which has continued to baffle readers ever since), they were an overnight sensation, selling out in weeks. In 1557, the seer published a second edition, adding another 289 verses to the original number.

He dedicated this volume to the reigning French king, Henri II—and it may have been this which drew him to the attention of Queen Catherine de Medici, who was a believer in occult mysteries. She invited Nostradamus to Paris in July 1556 and asked him to cast a horoscope for her children. What the seer told her is not recorded, but there are very clear references to the fate of her family in the Centuries. Of the seven children, three became kings of France, but six died young in tragic circumstances—all as predicted by Nostradamus.

The queen’s patronage assured the seer from the south his fame, and he was soon besieged by courtiers and nobles seeking predictions, cures, and horo-scopes. However, this success was to be short-lived. Claims for the accuracy of Nostradamus’ visions soon came to the attention of the authorities, and it was only after “a certain lady” warned him of impending arrest that Nostradamus slipped away from the court and returned home to Salon.

There, made wealthy by the royal patronage, he settled into a comfortable life with his wife and their six children. Curiously, he seems never to have been troubled by the authorities again, despite publishing a third edition of the Centuries, containing a further 300 quatrains, in 1558. This last volume now only survives as part of an omnibus edition, now called The Prophecies, published after his death in 1568. This version contains one unrhymed and 941 rhymed verses, grouped in sets of a hundred, and one of forty-two. Apparently, another fifty-eight quatrains existed but these vanished without trace.

Nostradamus died in 1566, aged sixty-three. On the evening of July 1, having already received the last rites, he told his secretary, Jean de Chavigny, “You will not find me alive at sunrise.” The next morning he was reportedly found dead, lying on the floor next to his bed. His widow commissioned a plaque which bore the inscription:

Into Almighty God’s hands I commend the bones of illustrious Michel de Nostredame, alone judged by mortal men to describe in near-divine words the events of the whole world under the influence of the stars.

The Book of Images

Nostradamus’ reputation as a prophet and seer is paramount, but in 1994 a volume was discovered that threw new light on his work and in the process captured the attention of the world. Two Italian journalists, Enza Massa and Robert Pinotti, were browsing the collection of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma (Central National Library of Rome) when they came across an illustrated codex entitled the Vaticinia Michaelis Nostradami de Futuri Christi Vicarii ad Cesarem Filium D. I. A. Interprete (The Prophecies of Michel Nostradamus on the Future Vicars of Christ to Cesar his son, as expounded by Lord Abbot Joachim), or the Vaticinia Nostradami (The Prophecies of Nostradamus) for short. In the library catalogue its shelf mark is the rather anonymous Fondo Vittorio Emanuele 307 (VE 307), which perhaps accounts for the fact that it had not been noticed before. It contained a collection of eighty remarkable watercolour images, clearly representing mysterious and hidden meanings. They included a number of ecclesiastical figures—numerous popes, cardinals and so on—as well as symbolic images of hands holding swords, seven-spoked wheels, banners and a gallery of curious creatures. The presence of so many people wearing the papal crown has led several commentators to suggest that The Lost Book is a version of a thirteenth-century book known as the Vatician de Summis Pontificibus, which consists of a collection of prophetic statements made by various pontiffs throughout the history of the Holy See.

The mysteries of The Lost Book

Several editions of Vatician de Summis exist and there are a number of undoubted parallels to the imagery of the Vaticinia Nostradami. However, this doesn’t mean that the latter was anything more than influenced by the earlier work. The reference in the title to the Abbot Joachim, suggests a link with a much earlier, millennial prophet, Joachim of Fiore (1135–1202), who wrote several books based on an interpretation of the biblical Book of Revelations in which he prophesied that a new age would dawn in which the Church would no longer be needed. This heretical view influenced several important leaders of the day and a number of (possibly spurious) prophecies were later produced in his name. However, it seems unlikely that the Vaticinia Nostradami had anything more than a passing connection with Joachim’s work.

Looking through the volume, Massa and Pinotti were astonished and excited to find the name “Michel de Nostredame” inscribed on the title page. Then, in the back of the volume, they found a postscript dated 1629, apparently added by one of the librarians through whose hands the book had passed, which stated that the book had been presented by one Brother Beroaldus to Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, who would later become Pope Urban VIII (1623–1644). The same covering note suggests that the images were devised by Nostradamus but painted by his son César de Nostredame (known to have studied art), who later sent the book to Rome as a gift. A letter written by César to the French scientist Fabri de Peiresc in the same year (1629) mentions a collection of miniatures painted by himself, and a booklet destined to be a gift for King Louis XIII. Could this booklet be The Lost Book? No precise evidence exists to connect the two, but there is no reason to discount the possibility.

What we can say, with reasonable certainty, is that César de Nostredame was an artist (though admittedly of little talent) and that he refers to a book of images he had painted. These could well be the original volume now known as the Vaticinia Nostradami or The Lost Book of Nostradamus. If so, there is every reason to believe that the images were painted at the behest of Michel de Nostrademe himself, possibly even from sketches he had made, and that they constitute a series of visual references to the Centuries. César himself never showed any sign of following in his father’s footsteps, so the idea that he might have originated these himself seems unlikely.

The story of the discovery was an overnight sensation and the volume, now known as The Lost Book of Nostradamus, was much publicized. The Nostradamus Code (Destiny Books, 1998), by Ottavio Cesare Ramotti, claimed that the images related directly to the Centuries and that with them the key to a more accurate understanding of the prophecies could be extracted. This was followed in 2007 by a History Channel documentary, The Lost Book of Nostradamus, in which even more extravagant claims were made. Since then, the subject of The Lost Book has become a frequent topic on websites ranging from the intriguing to the ridiculous.

None of the writers or film makers made more than a passing reference to a fact that leapt out from the pages of The Lost Book the first time we saw a selection of the images—that many of the paintings reflect the symbolism of the tarot. Once we began to examine the available pictures in detail, we became ever more convinced that what we were seeing was a series of visual glyphs which would, once completed, have formed the basis of a tarot designed by Nostradamus himself.

The Lost Tarot

A variety of claims have been made for the origins of tarot. Some have suggested that its beginnings date back as far as ancient Egypt, or to the Templars, or to the Gypsies—but most experts now see this most popular of all predictive systems as beginning some time in the late Middle Ages, growing out of the older practice of cartomancy, the reading of fortunes with playing cards. Of one thing there is no doubt: tarot cards were all the rage during the period in which Nostradamus lived, so it’s quite possible that he considered making his own set. And, if so, what more likely scenario is there than that he should have drawn upon his own visionary skills to create what would have been a unique system, combining the archetypes of the predictive tarot with his own prophetic gifts.

Once we began to look into the imagery of The Lost Book, we found that not only were there a number of pictures which exactly matched those of the basic tarot archetypes (the Burning Tower, the Hermit, the Wheel of Fortune, and the Fool, to name but four), but that the remaining series of paintings contained, hidden within them, references to many more. We became increasingly convinced that we were looking at an incomplete set of images destined to be become a tarot—a Nostradamus tarot.

Tarot and Nostradamus

Did Nostradamus begin to create a tarot deck based on his visionary insights? We became convinced that he did, but that he was prevented from completing it by death, and that the images he had begun to prepare languished for many years and were consistently misunderstood as something they were not.

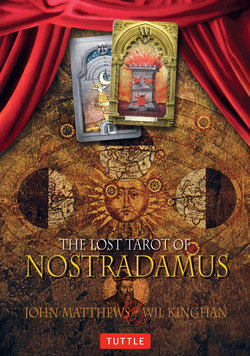

With increasing excitement, we began to research the deeper meanings of The Lost Book, and very quickly found that we had a complete set of the Major Arcana, and many of the Minors. After several months of intense work, we had in place a full deck of seventy-eight cards, all of which drew upon the paintings from The Lost Book. In short, we had succeeded in completing the work begun by Nostradamus himself, to create The Lost Tarot of Nostradamus.

Throughout the work, we chose to accept, in the broadest terms, that Nostradamus was a genuine seer and that his collections of prophecies have a measure of validity. This doesn’t mean that we accept the wilder interpretations, especially those which have been used recently to suggest the imminent end of the world! However, because of the nature of The Lost Tarot of Nostradamus, such questions are less important than is normally the case, because we’re not treating Nostradamus’ work as prophetic, but as predictive—a very different thing. Questions concerning the validity or otherwise of the Centuries may be left aside for the moment—though we will later suggest a way in which the quatrains can be utilized to support or augment the readings created by the tarot. Nostradamus’ writings have always been used to suggest events ranging from the historic to the cosmic—they have never been used to interpret personal dilemmas. That has been left to the tarot. Now, for the first time, these two powerful predictive systems are brought together, as they were always intended to be, as The Lost Tarot of Nostradamus.

Reinterpreting the Images

When we first looked at some of the images from the VE 307 Vaticinia Michaelis Nostradami manuscript, the first thing that went through our minds was how much tarot imagery was present. Pictures such as “the Wheel of Fortune” and “the Burning Tower” are instantly recognizable, others less so; while some are more alchemical and obscure. Indeed, the manuscript could more accurately be described as a notebook of sketches for a tarot, plus some other things. However, enough of the imagery from the tarot we are familiar with today was present in this amazing sketchbook to excite us and give us the resolve to somehow complete this lost work by one of history’s greatest prophets.

Religious imagery

There are a wealth of popes in many of the drawings. They people the Major Arcana especially, where we are used to seeing other figures. Many are of a heretical nature more redolent of the anti-Catholic demonization campaigns of the Reformation. Undoubtedly there are many influences coming together in the drawings: imagery from the so-called “Prophecies of the Popes,” alchemical references, zodiacal and celestial images that are juxtaposed with the imagery of the tarot. The most prevalent imagery is, of course, rooted in the world of the Roman Catholic Church of the late Renaissance, but the most interesting aspect is the juxtaposition of an esoteric understanding with an orthodox one, as well as the undeniable presence of an anti-cleric streak.

The symbolism within the imagery of The Lost Book is remarkably consistent. It is also very ecclesiastical. Inevitably so, when one considers when, and for whom, it was produced. There are, thus, many papal figures, which may be seen not only as representing the Supreme Pontiff himself but also the power of the Holy See in Rome. Whatever its shortcomings, the Vatican was perceived as a gateway to the Kingdom of Heaven—hence the proliferation of keys, which represent the Keys of Peter, the actual keys to the realm of Heaven, as well as papal crowns (often set above the kingly), which are intended as a reminder of the power of the Church.

No one is in full agreement about the symbolism of the mighty Triple Crown, which shows up a great deal in The Lost Book. Popes have worn this tiara since the Middle Ages, if not sooner, and for some it represents the threefold authority of the Church throughout the cosmos. The crowning of the pontiff is still accompanied by the words:

Receive the tiara adorned with three crowns and know that thou art Father of Princes and Kings, Ruler of the World, Vicar of Our Savior Jesus Christ in earth, to whom is honor and glory in the ages of ages.

In addition to these powerful symbols, a veritable bestiary of creatures, both natural and supernatural, throng the book. Doves, eagles, snakes, lions, sheep, and bears rub shoulders with unicorns, dragons, and serpents.

All these are open to ecclesiastic interpretation. Serpents mean evil; eagles are imperial; doves mean peace; lions are strength; sheep could refer to the Lamb of God, the congregation or the weak and needy. They form something akin to a language of creatures, an index of references which any educated person would have recognized immediately and been able to supply the meaning. What is interesting, however, is the way Nostradamus juxtaposes some of these familiar images so that we see a pope attacked by a unicorn, or offering food to bears, or a mythical gryphon holding a priest’s staff. Just as in his writings, he seems to be poking fun at the establishment of the time—and possibly risking an unpleasant experience at the hands of the Inquisition.

Other forms of symbolism

The presence of both astronomical and astrological imagery throughout The Lost Book is not at all surprising. Though officially frowned upon by the Church, such disciplines were still considered to play a part in understanding the universe – providing, of course, that those who followed such abstruse ways remembered that any suggested variation in the shaping of the universe was strictly forbidden and probably heretical. Thus, we find references to a possible heliocentric universe, which was still considered heresy during Nostradamus’ lifetime. There are also several images of astrologers consulting books of ancient knowledge, and a significant number of astrological signs, ranging through most of the houses. Of course, many of these feature in the symbolism of tarot, making it comparatively easy to read the hidden clues left by Nostradamus as we set about recreating The Lost Tarot. That the seer himself was no stranger to astrology is clear from the following note he made in a letter to César:

Through the omnipotence of the eternal God we are governed by the Moon, and before she completes her cycle she will reach the Sun and Saturn. According to these celestial signs the reign of Saturn will then return, for which reason, according to my calculations, the world is drawing close to an inevitable revolution.

Once again, Nostradamus is telling us that he can see into the future in more ways than one, and that his vision includes the vast tides of time governed by the houses of the zodiac.

Exactly how much of the imagery is tarot and what is not could be a matter for debate, but it is important to remember that the familiar symbolism in modern tarot was much less fixed in Nostradamus’ time than it is today.

Overall, however, it is clear that the deviser of the images for The Lost Book knew a great deal of the spiritual symbolism current at the time, and was not afraid to play with it in all manner of daring ways. It is for this reason, we think, that the book vanished for so long into the Vatican archives, only perhaps coming to light in our own time now that a more open-minded attitude exists. The enigmatic note on page 83 of the manuscript suggests that its author was leaving a very great clue to the identity of its source of inspiration—one that might have come to light even if his name had not been inscribed on the book:

To the Honest Reader: Those preceding him [Nostradamus] are missing here by reason of the injuries of devouring time, according to divine will … uttered not by possession but in sleep, and not by divine inspiration … but by other ways, for our forebears have sent us a soothsayer of good and scarce possession.

Using the images

Surveying the material wasn’t easy, as picture references for the pages of the manuscript are surprisingly hard to find, and at this stage we hadn’t approached the library where the manuscript is held. However, we were able to assign images to all the Major Arcana cards without difficulty. This convinced us that we would indeed be able to recreate The Lost Tarot of Nostradamus.

Of course, it’s apparent that, from the point of view of a functioning tarot, the manuscript is an unfinished work. While many of the familiar images are there in striking detail, others are not, especially in the case of the Minor Arcana. It’s clear that if Nostradamus intended to create a tarot of his own, these were his ideas and his reinterpretation of already recognized tarot forms, which he didn’t extend to every card. Consequently, we have used the drawings in the manuscript to construct a functioning tarot rather than resort to making anything up or bringing in supplementary drawings from other manuscripts. We have endeavoured to finish the work of creating a Nostradamus Tarot, and in the process have used nearly all the drawings contained within the manuscript in one way or another. Only a small handful were deemed unsuitable to use, being only partial sketches without any context, repetitions, or very obscure symbols.

There are about eighty images, which range from small, quick sketches to large, colorful plates with much more detail. All the Major Arcana images were well represented, but we soon realized that the Minor Arcana would be more difficult to research. This is unsurprising, as in many early tarots the so-called “pip” cards are simple repeating shapes styled similarly to playing cards, which, in reality, they probably were. But with some head-scratching, and even a bit of intuition (plus John’s thorough research of early tarot), we managed to get a set of images from the material which we felt matched well with traditional tarot meanings. I think the fact that we were successful in this underlines the presence of tarot material in the manuscript and strengthens the idea that Nostradamus was genuinely working on, at least, an outline for a tarot.

Creating the deck

Once we were able to look at all the available imagery, we began to get a feeling for how it could be structured. Much of Nostradamus’ symbolism is strange and obscure to modern eyes, unused to the religious iconography of the 1600s, and we knew that we would need to find some way of giving the suits of the deck a recognizably distinct style This was especially important, as we had decided to veer away from the “easy option” of simply using symbols (coins, for instance) for the Minors. We wished, instead, to use as much of his art as possible. Of course, this resulted in a set of Minors where it was, at times, difficult to tell whether it was wands or cups being shown!

To get around this, and to make the deck richer in symbolism, we returned to the idea of “framing” the original images. I designed five sets of distinct frames, modelled after Renaissance sculptural niches, triptych and altar frames, and picture frames from the period. These were also designed to reflect the alchemical process and the cosmological ideas current in Nostradamus’ time. For the suit of Suns, I decided to use planetary and solar symbolism and colors; for Moons, the lunar cycle was an ideal subject and incorporated some drawings by Galileo. The suit of Spheres reflects the work of Nostradamus’ near contemporary Johannes Kepler and the idea of a sequence of celestial spheres, each nesting within a framework of the preceding Platonic solid. The suit of Stars uses the astrological and astronomical ideas current at the time of Nostradamus. In each case we wanted to reflect parts of the world of Nostradamus—the thought and science of his time.

Our initial desire was to utilize high-quality photography of the drawings within our period-style frames. Apart from distinguishing the suits from one another more easily, frames helped the overall look of the tarot for the simple reason that the drawings are, at times, unfinished, and, like quickly executed sketches, are sparse, lacking in detail and seem rather “naked” on the page. However, this approach proved not to be possible, due to restrictions on the use of the original photography held by the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Rome and on any new photography of the manuscript owing to the “nature of the subject”. This left us in quite a dilemma as the images of the Nostradamus pictures that are in the public domain are not of good enough quality for any kind of serious reproduction. So we decided that I would use the extant references to redraw Nostradamus’ sketches as accurately as possible, and this I have done, keeping as faithful to the originals as I can.

In approaching the reconstruction work on the drawings, I first concentrated on creating all the frames, and then moved on to the drawings themselves. These are watercolor ink line drawings and, as I had decided to work digitally, I had to first create some brushes in Photoshop, to emulate the slightly calligraphic nature of the pen that the artist had used. With these, I carefully retraced all the line work, having to reconstruct very dark or obscure areas. During this process I found myself using quite a few different brushes, as the line work changed between many of the drawings. However, from an artist’s perspective, I feel sure that the drawings are all by the same person.

After the line stage I reworked the color washes and inked portions and adjusted the colors. On one or two of the drawings, the reference shots were very poor and the colors had to be derived from looking at similar images in the manuscript. The Ace of Moons is one such example, where the color on the dove and fountain could hardly be discerned. However, for most of the images it was possible to follow the original color scheme. At no point did we alter or change any of Nostradamus’ drawings, apart from isolating a figure from a group where it wasn’t appropriate to have other figures intruding on the scene, and the addition of some ground for figures to stand on in some of the cards.

For those that are curious about such things, I worked using Adobe Photoshop CS2, Fractal Painter X, and ArtRage 2, running on an Apple iMac G5 using a Wacom pen tablet for sketching.

Redrawing all the line work was an arduous task, but I am happy with the result and the completed work brings us as close as we can get to the vision of Nostradamus’ unfinished tarot.

Shaping the Tarot

Right from the start we recognized that there were very clear images in The Lost Book which represented the Major Arcana of the tarot. With the Minors, however, although we could see many reference points, both in the larger images we had selected to represent the Majors, and in the scattered images that were left, were they enough to illustrate the Minor cards? In the end we found there were, and that the way they so often fitted the traditional structure of the tarot strengthened our belief that we were on the right track. There were, however, almost no clues as to whether the suits would follow the normal sequence, or how the court cards would be represented—or even what names they might have had—assuming they did not follow the normal attributions of Swords, Wands, Cups, and Pentacles. After many months of work and meditation, we came up with three suits that we felt reflected the internal imagery of the original writings of Nostradamus, and a fourth which we “borrowed” from another great Renaissance thinker, Johannes Kepler. This gave us four suits, as follows:

Suit of Stars = SWORDS

Suit of Suns = WANDS

Suit of Moons = CUPS

Suit of Spheres = PENTACLES

This represents the cosmos as it was understood by Nostradamus and his contemporaries, with the final suit, Spheres, coming from Kepler’s work. There are a huge number of cosmic references in the Centuries, and we tried to reflect this in our choice of imagery. Again, the sometimes fragmentary pictures seemed to reflect his exactly and left us feeling we had faithfully reflected Nostradamus’ vision.

When it came to the peopling of the court cards, we were convinced that Nostradamus himself would have chosen figures, both from his own time and earlier, who could represent the underlying patterns in his writings. We therefore decided that the four courts should be represented by figures from history who were alive in Nostradamus’ lifetime, or soon after, about whom he might have known enough to recognize the inner archetypal qualities. We also looked for people who best equated to the traditional meanings of the tarot and who, where possible, represented the most important aspects of esoteric life during the periods of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Thus, we have astrologers, astronomers, physicians, philosophers, spiritual and temporal leaders, and, of course, the apprentices and neophytes who represent the development of the four areas of society.

In this way, each of the four suits represents a particular aspect of the world and the court cards are aligned with this. The suit of Stars is represented by religious figures, the suit of Suns by monarchs, the suit of Moons by occultists and philosophers, and the suit of Spheres by alchemists and scientists. Finally, to bring to the shape of the deck another element which would have been immediately recognized as important by people at the time, we added five significant metals, all of them connected to the science of alchemy—very much in vogue, though seen as suspect, in Nostradamus’ lifetime. Gold stands for the Major Arcana, mercury for the Stars, copper for the Suns, silver for the Moons, and lead for the Spheres. Each of these is represented by the colors of the arches which frame the images in The Lost Tarot.

The Tarot and the Prophecies

As we have stated above, the prophecies, especially those written in such deliberately obscure language, are open to many kinds of interpretation. We are certainly not suggesting that we have any more knowledge or understanding of the meaning of the Centuries than the many experts who have spent years laboring over their interpretation. However, we do think that the application of tarot meanings to many of the quatrains reveals some interesting parallels, and in some instances even suggests new meanings. We also thought that, since we were recreating a tarot originally sketched by Nostradamus, we could add a further aspect to the use of the deck by applying couplets to each of the cards. These are drawn directly from Nostradamus’ own writings in the Centuries, and are newly translated by Caitlín Matthews, whose note on the problems—and rewards—of translation appears overleaf (see pages 27–8).

We asked Caitlín to concentrate on the literal meanings wherever possible, though always keeping an eye out for the wordplay and puns with which Nostradamus liberally seeded his work. The idea was to select two lines from the existing quatrains, either the first and second, the second and third, or the third and fourth, creating fresh combinations from the deeply esoteric meanings of the verses. What happens when this is done is extremely interesting. It not only changes the possible interpretations of the quatrains but also shifts the focus of the existing paired lines. Thus new interpretations bubbled up before we had even begun to compare the selected lines with the meanings of the cards. As we did this we discovered something astonishing: again and again, the interpretations of the new couplets fitted the imagery and meanings of the cards exactly. For example, for the Lovers, in the original Quatrain 83 from Century VII, we found:

D’opression grand(e) calamite

L’Epithalame converty pleurs et larmes.

From great oppression and calamity

The wedding contract transforms tears and sighs.

While, for the IX of Suns, a card always associated with struggle and imminent threat, we found, in Quatrain XII:59:

L’accord et pache sera du tout rompue;

Les amitiez polues par discorde.

Accords and pacts will be broken;

Friendships will be undermined by discord.

Such precise mirroring between the quatrains and the card meanings added even further to our belief that Nostradamus was not only creating his own tarot but that he was familiar with the traditional cards and their meanings.

The inclusion of the new couplets allows the tarot user an unprecedented opportunity to create original quatrains by adding two of the couplets together. The effect of this is itself quite revelatory. Again and again we found that by breaking down the quatrains in this way, and then allowing the randomizing effect of the tarot cards to bring two couplets together, made more sense than before! This may be no more than an accident, or possibly it points to the extraordinary quality of Nostradamus’ work—or it may be that we are following in the footsteps of many before us and simply seeing things that are not there. We leave it to the users of The Lost Tarot to make up their own minds.

Last, but by no means least, we decided to match some of the more clearly defined interpretations of the quatrains to the cards of the Major Arcana. Once again, we were astonished how relatively easy it was to do this. Taking the most traditional and basic interpretations of specific cards, and matching these to the most widely accepted prophetic readings of Nostradamus’ words, we found that many of these worked extremely well. For example, we matched card XV, the Devil, with Quatrain II:24:

Bestes farouches de faim fluves tranner:

Plus part du camp encontre Hister sera.

Hungry wild beasts will cross the rivers.

The most part of the field will be against Hister.

This is generally accepted to be a direct reference to the rise to power of Adolf Hitler. Given the associations of the card with deceit, lies, and trickery and the expectation that the reader, or someone close to them, will do anything to get their way and rise to the top of the heap, this seemed particularly apposite.

Even more exact, from the original imagery of the Burning Tower, to the accompanying couplet and the widely agreed interpretation, we arrived at Quatrain X:49:

Jardin du monde au pres de cite neufve

Dans le chemin des montaignes cavees …

In the Garden of the World near the New City

On the road of the hollow mountains …

The prophetic reference here is to the attack on the Twin Towers in New York, on September 11, 2001, and also to the hubris of capitalism which we are seeing in our own time. The pairing of Nostradamus’ words with the inherent meaning of the tarot cards seemed too precise to ignore. We’re not suggesting that these prophetic messages are a part of a personal reading; they are merely there to show how closely the writings of the seer can come to the traditional interpretation of the tarot. However, if looked at in an impersonal way, we may well find echoes of our own situations within these cryptic interpretations.

This leads us inevitably to an aspect of Nostradamus’ work that is impossible to ignore. The Centuries have, since they were penned, been seen, again and again, to offer only words of doom. They are, it must be said, often grim reading, but they are also, as we have indicated, open to many different kinds of interpretation. In recent times we have heard a great deal about the end of time in 2012, buttressed by the misunderstanding of Mayan calendrical glyphs, which in fact only point to the ending of one cycle and not to all of time. In the same way, Nostradamus’ prophecies are almost universally interpreted as referring to vast tidal waves of death and destruction. But there is a simpler, more intimate side to the Centuries, which we have sought to extract. Belief or otherwise in such things is, of course, the prerogative of the individual. However, it is important to realize that the oracles of The Lost Tarot are not intended to offer any kind of prediction of the future on a global scale. They are, simply and directly, images that, in the context of tarot, offer us advice and pointers to ways in which we can deal with issues in our lives. The following section offers further suggestions on how to interpret the new quatrains.

Translating the Quatrains

Translating Nostradamus is a daunting task. He not only wrote in sixteenth-century French, with seemingly familiar words that have since shifted meaning or nuance, but he wrote poetically, inverting words, punning, and alluding darkly to matters that he wished to cloak. In this context, I’ve pursued clarity of translation and tried to convey the implicit metaphor; this has sometimes meant using more words in English than are conveyed by the French. I’ve put brackets around these to indicate where this has been necessary; this has sometimes occurred because it isn’t always possible to lift just two lines from a quatrain, where the meaning is clarified by the remaining lines.

Nostradamus wrote at a time when religion and statecraft were beginning to abrade each other’s authority. The warlike intentions of the French upon Italy and the Papal States, the rise of Protestantism in Northern Europe, and the very recent expulsion of the Jews from Spain were all in the pot together. Nostradamus purposely cloaked his Centuries, using words that couldn’t definitively point to religious or state matters. For healers, prophets, and astrologers, the Inquisition was an ever-present deterrent, and he needed to be careful. For example, he frequently uses the word seul (alone) to refer to monks or priests, in the sense of them being “solitaries,” when an explicit mention might have brought suspicion upon him. He seems also to have embedded an anagram of the various French kings called Henri in the word Chyren—the “y” in the English “Henry” being interchangeable with the “i” in the French “Henri.” Henri II and Henri III both reigned during his lifetime, but some of his prophecies refer to the future Henri IV of Navarre, who was born a Huguenot and became a Catholic on his accession. Others think Nostradamus speaks of a King Henri V yet to come.

Some of Nostradamus’ emblematic references may derive from the sixteenth-century Orus Apollo, a pair of volumes in verse epigrams, purporting to explain Egyptian hieroglyphs. Without the critical help of the Rosetta Stone, not to be discovered for another two centuries, this speculative work guesses at meaning, but Nostradamus had certainly read it as some of his code words are derived from it: grasshopper means “mystic”; star stands for “God and destiny.” He often uses animals and classical references to signify countries or groups of people: for example, Neptune often indicates Britain; Venus is sometimes Venice; and mastiff usually refers to “an invading general.” But he isn’t above wordplay, homonyms, hidden meanings, and, of course, his own code words, not to mention, other tricks. For example, the word mabus, which appears in Quatrain II:62, has excited many commentators: if it is held up to a mirror, it reads “sadam” …

When there are so many theorists and others intent to steer Nostradamus’ Centuries through the goalposts of their chosen agenda—Redemptorist, astrological, alarmist, or conspiratorial, among others—we’ve tried to let the quat-rains speak for themselves, through their metaphors and images. Metaphor is the language of seership and prophecy, after all: it is the first language of the soul, and the way in which our imaginations receive and embed information. After that, everything is a matter of interpretation.

Finally, although we have worked from the most authoritative and reliable texts, the Centuries were copied and recopied many times from the original publication, with the result that misreadings, misspellings, and even intentional reinterpretations crept into the text. We have done our best to address these factors, but you may find yourself making your own translations, which might differ from ours. This is one of the reasons why the quatrains are so open to reinterpretation by virtually every person who attempts to understand them.

NOTE: All our card interpretations include a reversed meaning. If you wish, you may ignore these and turn the card the right way up; however, these cards do often fall in reverse for a reason, so be sure you want to change them before you do so.